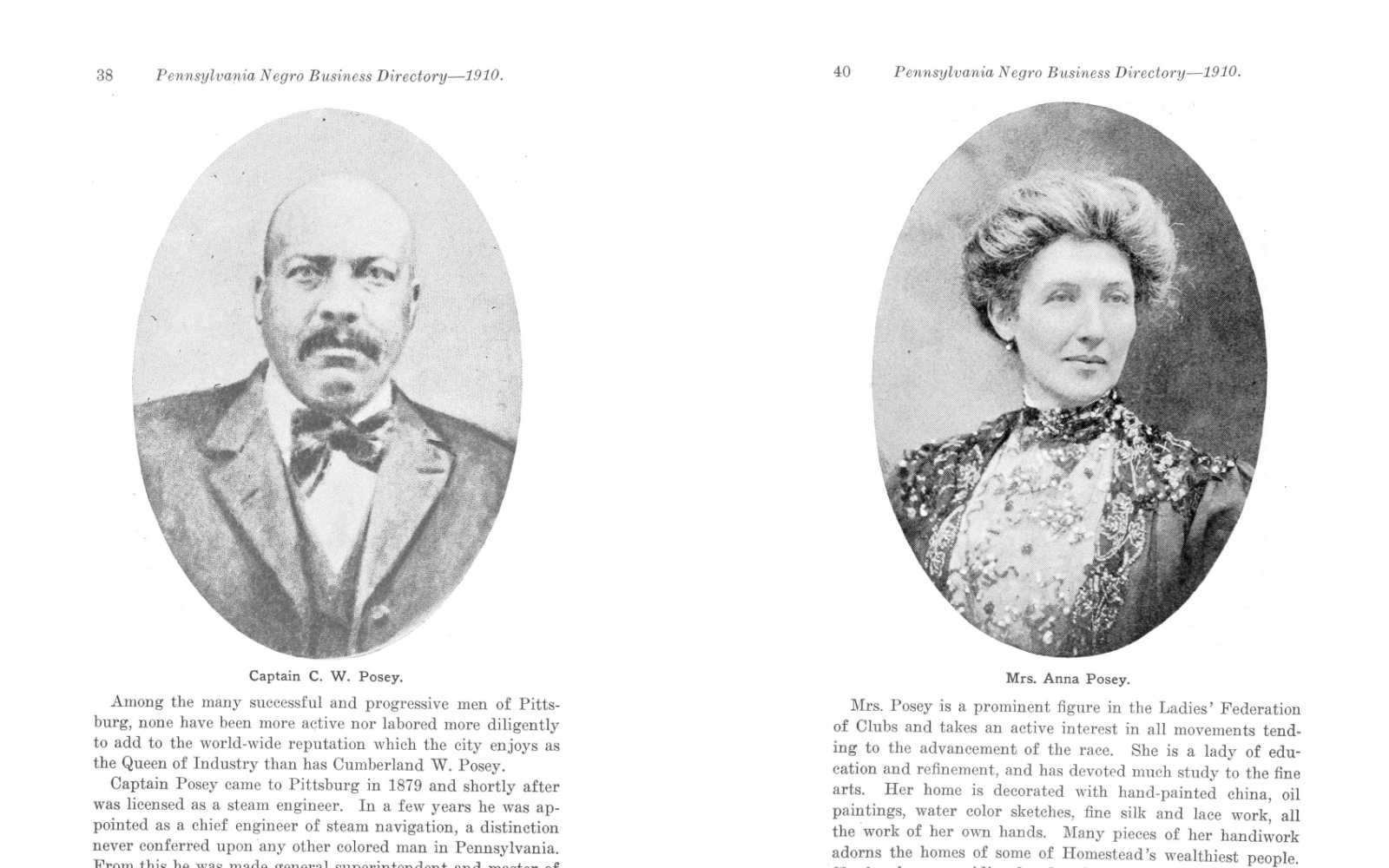

By Brianna Horan | Images of Cumberland “Cap” Posey and his wife Anna Posey.

The Lasting Legacy of Cap Posey

The Lasting Legacy of Cap Posey

For the nearly 12 million immigrants who arrived in the United States between 1870 and 1900, the America Dream shone as a beacon of economic opportunity as they left behind famine, job shortages, rising taxes, and political or religious persecution in the Old Country. But for the millions of African-Americans living in the United States during the same time period, less than a generation removed from slavery, America’s reality meant racial violence and lynchings, the poverty trappings of sharecropping, barriers to education, and an economy that drew stark lines between “white jobs” and “Black jobs.” Cumberland Willis Posey, came of age and established himself as a titan of industry on the Monongahela River.

Posey was born into slavery in 1858 along the Port Tobacco River in Maryland. As Mark Whitaker writes in his book Smoketown: The Untold Story of the Other Great Black Renaissance, “a river called out to him from his earliest days.” After Emancipation, his father moved his children progressively north to Winchester, Virginia, and then to Belpre, Ohio, as Posey was entering his teenaged years.

Belpre, which sits on the Ohio River, is where Posey first found employment on the water, sweeping the decks of a riverboat named Magnolia at the age of 19. He studied the boat as much as he worked on it, watching the assistant engineer keep the coal- and wood-fed fires burning evenly, and observing the chief engineer as he monitored the boat’s pressure gauges. He gained an understanding for how each piece of equipment worked in concert to turn steamboat’s paddlewheel and propel the boat forward. And he set a goal of running the engine room of a steamboat, a position that wasn’t available to African-Americans at that time. Posey’s employer believed in Posey’s abilities, however, and helped him find a job as an assistant engineer on a steamboat called the Striker.

A year later, Posey became the first Black man to receive a chief engineer’s license, and a riverboat operator named Stewart Hayes hired him to oversee the operation of several vessels. Posey earned a salary of $1,200 a year as he continued to learn the ins and outs of the steamboat business, shipbuilding, and engine maintenance. He also earned a nickname of respect up and down the Ohio River: Captain Posey, or “Cap” for short.

Traveling the waterways, Posey met and fell in love with Angeline Stevens, a school teacher in Athens, Ohio, along the Hocking River. Anna, as she was known, was perhaps the first African American to graduate from high school in Athens, and she became a teacher at age 17. Because the African-American population in the town was small, white and Black students were taught together (though Black children were required to use separate coat hooks from the white children). By the time she was 20, the Athens Messenger newspaper wrote of her teaching skills, “Progress in the march of events is, in one direction, chronicled in the fact that Miss Anna Stevens, of African lineage, is teaching in the public white school… As a teacher she possesses rare tact and efficiency and her services in this line have been in wide demand.”

Despite the community’s “progress” in embracing Anna, thirty armed Athens men forced their way into the sheriff’s home to seize the keys to the town jail, then dragged an African-American farmhand named Christopher C. Davis from the cell where he was awaiting trial for accusations of assaulting a white widow. After giving Davis three minutes to pray, the mob hung him to death off of a bridge. This lynching intimidated many in Athens’ small Black community to leave town soon after. A little more than a year later, Anna accepted Cap Posey’s hand in marriage, and followed him to start a new life in Homestead, Pennsylvania, in 1883.

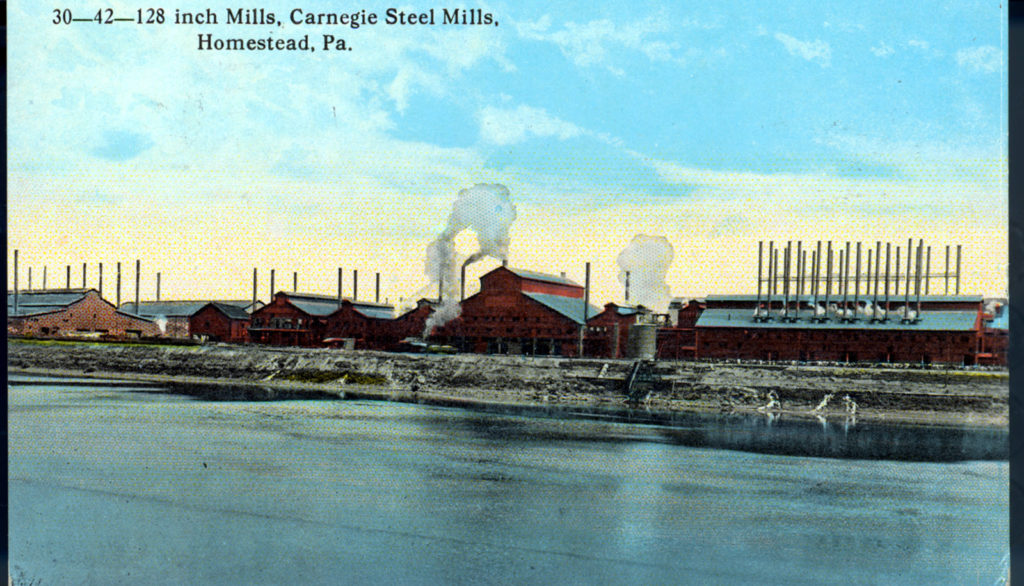

30–42–128 inch Mills, Carnegie Steel Mills, Homestead, Pa., Collection of Rivers of Steel.

As Whitaker notes in Smoketown, “Andrew Carnegie planted his flag in Homestead just as Cap Posey brought his new bride, Anna, there to live.” Carnegie had just bought one of the first American plants built by Henry Bessemer, who innovated a way to produce steel in mass quantities. Bessemer went into debt building his mill, and was forced to sell it after a worker’s strike and a decrease in demand for steel as rail expansion slowed.

As the industrialists amassed fortunes selling products forged by the labor of European immigrants and Black migrants, Cap Posey created his own opportunities, having amassed capital and experience that Black people did not commonly have access to at that time. In 1892, the year of the Homestead lockout and strike, Cap Posey made his first investment in coal boats, and went on to organize a small mining company, the Delta Coal Company. He later sold his shares in that company and founded Posey Coal Dealers and Steam Boat Builders, which manufactured more than twenty steamboats. By 1900 Cap was a major shareholder in the Marine Coal Company, earning an annual salary of $3,000 to manage the business. Whitaker notes in Smoketown that records indicate that Posey oversaw a payroll of one thousand employees and had nine white investors. Those accounts also describe him as a business partner of the region’s coke king Henry Clay Frick, and as a supplier to Andrew Carnegie’s mills. With those two men dominating so much of the coal and steel industries, it would have been almost impossible for Posey to have advanced the way he did in the coal mining and steel shipping businesses without working with Carnegie and Frick. Whitaker also points out that Posey would have been well positioned to recruit Black workers for Carnegie when he was seeking new workers who hadn’t been involved in the labor movement. “While blacks had largely been shut out of the mills and the unions before the [1892] strike, a decade later there would be 346 Negroes working in three Carnegie steel mills in the Pittsburgh area,” Whitaker writes.

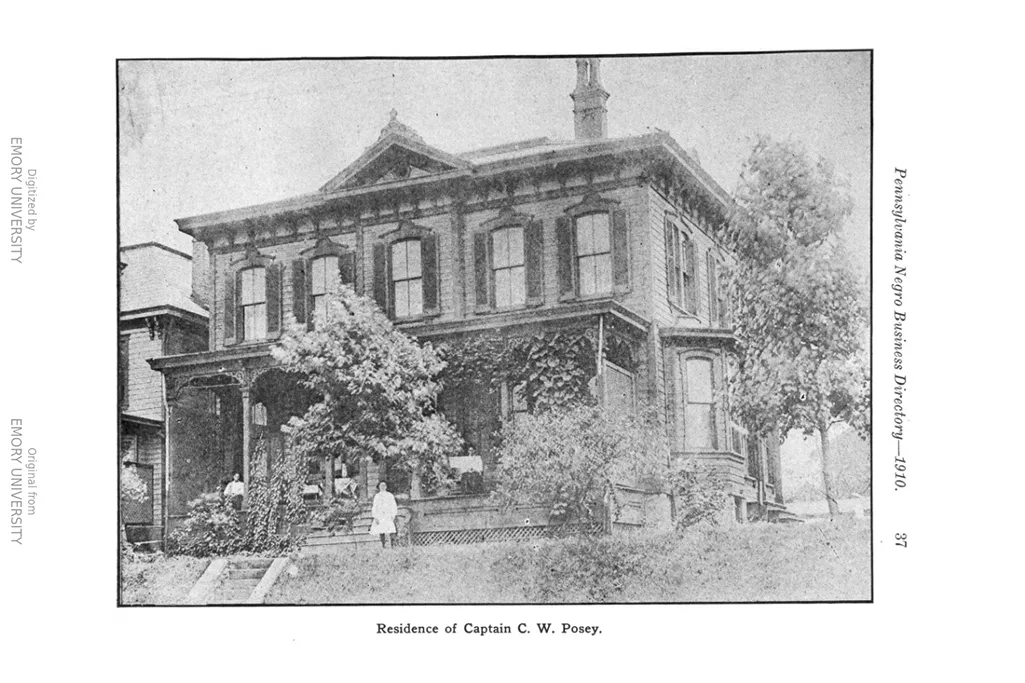

While Carnegie was becoming the richest man in the world, Cap became the richest Black man in Pittsburgh. He and Anna first lived in Munhall, an area largely populated by factory workers. Once Cap built his businesses, he also built a grand home on East 13th Ave. in Homestead – click here to see a photo of the massive two-story home in Pennsylvania Heritage. He and Anna enjoyed social and professional circles that orbited on a similar plane as the white industrialists of the Gilded Age, and occasionally crossed paths. A network of Black elite families was expanding, and the patriarchs started fraternal orders and social clubs like the Loendi Club in the Hill District, an elegant establishment modeled after the Duquesne Club. Women in this realm formed the Aurora Reading Club, which still exists today, to discuss books and organize support for local charities.

Posey Residence in Homestead from Pennsylvania Negro Business Directory, 1910.

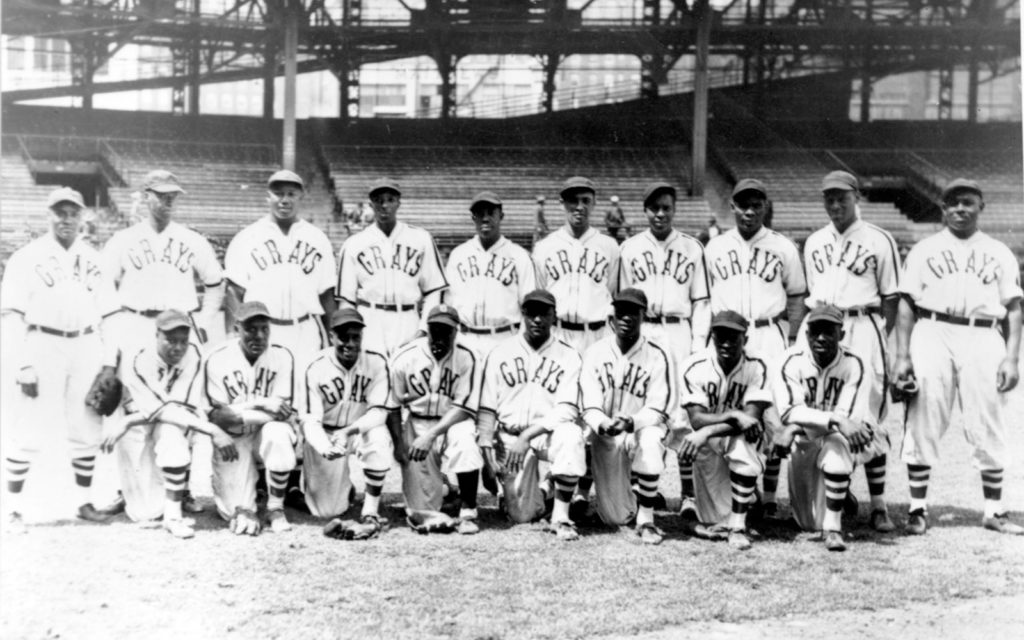

The Posey children were educated in Homestead’s schools alongside white students—segregated education was outlawed in Pennsylvania in 1883. Beatrix was the eldest, and would become a teacher like her mother. Anna and Cap named their second child Stewart Hayes Posey, after the steamboat owner who had first hired Cap as a chief engineer. The youngest was named Cumberland, like his father, but would be nicknamed “Cum.” At 19, Cum Posey joined a team of Black steelworkers—the Murdock Grays—who played at Homestead Park on weekends. That team renamed itself the Homestead Grays two years later, and Cum later became the principal owner, building the Grays into one of the best teams in the Negro League. Cum Posey was inducted into the National Baseball Hall of Fame in 2006 for his 35 years as a player, manager, owner, and club official.

Teenie Harris Photograph – Homestead Grays at Forbes Field, Collection of Rivers of Steel

Cap Posey still had one more lasting legacy to create. Seeing the success of press moguls like Joseph Pulitzer and William Randolph Hearst, and with a flurry of widely-read white-run newspapers in town, Cap Posey was keen to invest in a fledgling publishing venture in 1910. He was one of four investors in The Pittsburgh Courier, and was named the organization’s president.

The Lasting Legacy of Cap Posey

The Lasting Legacy of Cap Posey