Aluminum Illustrations, 1948. Illustration of aluminum smelting at Alcoa. Niziol Collection, Rivers of Steel.

By Ron Baraff, Director of Historic Resources and Facilities

Aluminum—Born of the Pittsburgh Spirit

Aluminum—Born of the Pittsburgh Spirit

This August, Rivers of Steel will host the second session of its three-day Sculptural Aluminum Casting workshop, along with another opportunity for newbies to try the casting process—the three-hour introductory Aluminum Casting Session. So we thought it would be a good time to share this article by Ron Baraff on the origins of aluminum and its industrial rise in the Pittsburgh region.

Aluminum is a Pittsburgh product—not because Pittsburgh had abundant supplies of bauxite ore, for she has not; and not because Pittsburgh had abundant hydroelectric power, for she has not. Aluminum is a Pittsburgh product because Pittsburgh, despite its reputation for smoke and grime, is primarily interested in men. Here in Pittsburgh as in no other community of the United States, does creative genius get a hearing and sound backing…. It was Pittsburgh that listened to an Ohio college boy with the vision of the possibilities of a new and light metal. Not only did it listen, but it gave substantial assistance.[1]

—Arthur Vining Davis, President of the Aluminum Company of America, 1927

The mantra of the contemporary moment is that Pittsburgh has reinvented itself, rising up on a new arc of innovation and ingenuity. The region is being heralded as the new, shiny beacon on a hill, setting the stage for the 21st century and beyond through robotics, biomedical research, and education. While we are moving forward in these fields, fostering civic and fiscal revivals, the very fact that Pittsburgh is a hub of innovation, capital, and ingenuity is as old as the grand metropolis itself. Since its incorporation, Pittsburgh has been a vanguard city, cloaking itself in the comfort of working-class ideals and mores, all the while inviting and nurturing capital investment, research, discovery, and innovation. It has been a leader in the development and success of the boatbuilding, steam power, glass, airbrakes, electricity, rail, oil, iron, and steel—revolutions that shook the world to its very foundations and inextricably changed the course of human development. Often overlooked, or at least underappreciated in all of the civic and economic boosterism that lead to the heralding the city as the “Iron and Steel City,” is the aluminum industry. The rise of the industry through the Pittsburgh Reduction Company and its later incarnation as the Aluminum Company of America (Alcoa) provided for cross-pollination and integration with other major industries, investors, and industrialists from the Pittsburgh region and was part of what has been described as the “Pittsburgh Spirit,” a mindset that encouraged investment and cooperation among Pittsburgh’s elite in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

Photograph of “Crown Jewels of the Aluminum Industry.” The large globule of aluminum at the right is the first run of aluminum made in 1888 by the Pittsburgh Reduction Company (predecessor of ALCOA). The smaller globules are those made by Charles Martin Hall in February 1886 by the electrolytic process he discovered. Niziol Collection, Rivers of Steel.

When American inventor Charles Martin Hall (1863 – 1914), along with Frenchman Paul Heroult, demonstrated the means for aluminum extraction and production in 1886, the stage was set for a new revolution in the metals industry: here for the first time was a way to economically produce aluminum.[2] This process, known as the Hall-Heroult process, attracted the attention of manufacturers and investors alike who saw the opportunities not just to make and market the lightweight, wide-reaching, and durable aluminum, but who also saw benefits for use in other aspects of industrial manufacturing. Among those who was attracted to the new world of possibilities was Pittsburgh industrialist Alfred Hunt. Hunt, whose initial interest in aluminum and the Hall-Heroult process was focused on how it could be applied to the steel industry in a process known as “killing” which would efficiently help to remove dissolved oxygen in the steelmaking process, came to be a central figure in the rise of new industry in Pittsburgh. For Hunt and Hall, efficiency and economy of scale were prime motivating factors, as they would go on to partner in the Pittsburgh Reduction Company and its later incarnation, Alcoa.

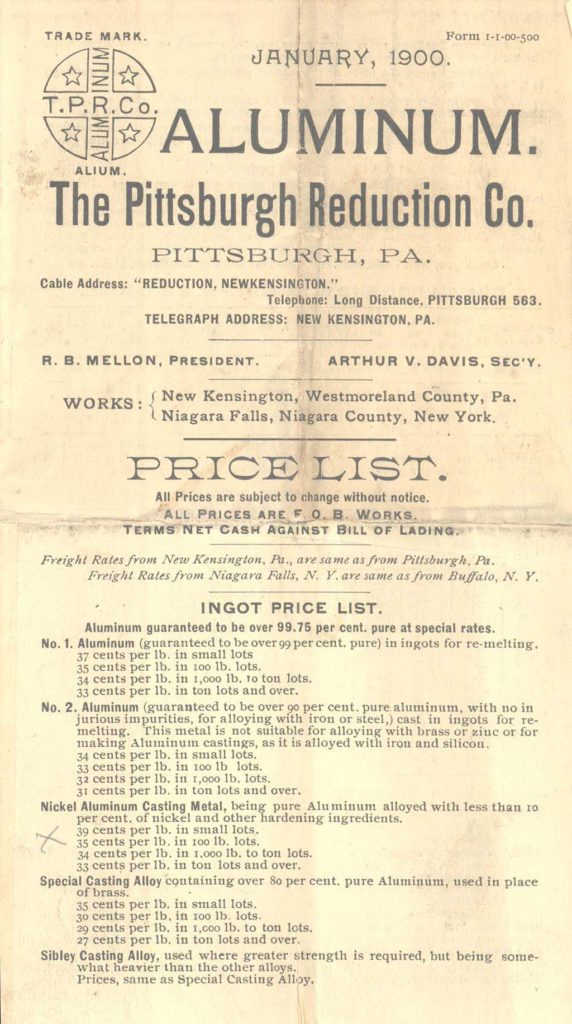

The Pittsburgh Reduction Company, Aluminum Price List, 1900. Founded by Alfred Hunt and Charles Martin Hall, the Pittsburgh Reduction Company was the predecessor to the Aluminum Company of America (Alcoa). Rivers of Steel Collection.

The most interesting thing to this Chamber, however, is that the Aluminum Company of America is a Pittsburgh industry. In the early days when there were only six partners in the business they were all Pittsburgh men connected with the steel companies and other companies of this city. Later on when it became necessary to get in more money, the Messrs. Mellon, Mr. Thaw and one or two others joined us, but they were all Pittsburghers. Since that time we have had practically no money put into the company so that it is as true today as it was then that the money of the company is Pittsburgh money.[3]

—Arthur Vining Davis

Hunt was not alone in his interest in aluminum. Being an “East Ender” in Pittsburgh—part of the enclave of rich industrialists who settled in Pittsburgh’s burgeoning East End—he worked hard to entice some of his neighbors to invest in his new venture. Some of the early investors were those whose fortunes laid in Pittsburgh’s dominant industries: Howard Lash and Millard Hunsiker from the Carbon Steel Company, Robert Scott from the Union Iron Mills, and George Hubbard Clapp and W. S. Sample from Pittsburgh Testing Laboratory. Their interest and investment enticed other titans of Pittsburgh like the Mellon Brothers, who were lured by the investment possibilities that the new industry would bring. They were early and eager investors, working hard to raise much needed capital, as well as providing legal advice where needed. Their concerns and money allowed Hunt and Hall to reinvest earnings into expansion of the company, taking a page from another fellow industrialist, Andrew Carnegie. The idea was to keep building for the future and long-term strategies.

The company was focused on the ideal of vertical integration—again based on the Carnegie model—to keep the profits at home, invest in needed raw materials and supplies, and bring all elements of production under one banner / company. Vertical integration provided a control over all facets of production, from the supply chain to production to end product distribution. This model was heavily rooted in the Pittsburgh tradition—Carnegie Steel, Westinghouse Electric and Airbrake, and the Heinz manufacturing empires were built upon it. Like the Mellon’s, George Westinghouse saw the opportunities that would come with the growth of the industry as it was applied to his Alternating Current (AC) power interests in Pittsburgh, but even more so in Niagara Falls, the aluminum reduction industry was heavily reliant on hydropower. Westinghouse Electric would “manage the building of one of the world’s greatest hydroelectric stations” without which the growth of the industry would have been stymied.[4]

Aluminum Illustrations, 1948. Illustration showing Charles Martin Hall and A.V. Davis showing “the Pittsburgh Spirit” making Aluminum. Niziol Collection, Rivers of Steel.

Another Pittsburgh East Ender who would play a large role in the success of Alcoa was Philander Knox, who served as President Theodore Roosevelt’s Attorney General. For over a decade the company “grew up in the shadow of the large trusts; steel, oil, tobacco, cotton, and pig iron.”[5] In 1903, President Roosevelt instructed Knox to initiate a series of lawsuits under the Sherman Antitrust Act of 1890, the first federal regulation of monopolistic business practices. Given Knox’s closeness as a poker buddy and neighbor of the founders of Alcoa (and United States Steel), the company managed to avoid the federal antitrust lawsuits. Operating under patent protections, their control of aluminum pricing, supplies, and distribution was deemed to be valid. While there were some later antitrust issues concerning their involvement in the international cartel, which produced roughly ninety percent of the world’s aluminum supply, the company remained mostly unscathed. The government-issued Consent Decree of 1912 and the coming of World War I a few years later, ended any ongoing and pending legal proceedings. Alcoa agreed to “stop all questionable practices” and ostensibly ended their involvement with the cartel.[6] They were able to withstand competition and ultimately dominate the global aluminum market.

In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, the Pittsburgh region was ripe with opportunity. The region was a hotbed of innovation, ingenuity, and investment. The crosspollination and investment of capital that built the early manufacturing industries of Pittsburgh ushered in a period of unprecedented growth and prosperity. This practice became the standard upon which the region was built and is still being built to this day. The “Pittsburgh Spirit” is as alive and well today as it was for Alfred Hunt and Charles Martin Hall when they launched the aluminum industry and changed the course of metals manufacturing worldwide.

[1] Speech to Pittsburgh Chamber of Commerce, Arthur Vining Davis, President of the Aluminum Company of America. Pittsburgh and the Pittsburgh Spirit, Pittsburgh Chamber of Commerce, 1927, p. 185

[2] Heroult developed a similar process in France, thus sharing the patent known as the Hall-Heroult process.

[3] Speech to Pittsburgh Chamber of Commerce, A.V Davis, President of the Aluminum Company of America. Pittsburgh and the Pittsburgh Spirit, Pittsburgh Chamber of Commerce, 1927, p. 177

[4] Skrabec, Quentin R.. Aluminum in America: A History. McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers, 2017. P. 56, Kindle edition

[5] Ibid, p. 64

[6] Ibid, p. 65

This article was first published in the catalog for student curated exhibition, Metal From Clay, at the University Art Gallery, University of Pittsburgh, October 24, 2019.

Aluminum—Born of the Pittsburgh Spirit

Aluminum—Born of the Pittsburgh Spirit