The Battle of Homestead

The bloody confrontation that occurred in Homestead, Pennsylvania on July 6, 1892 was one of the pivotal moments in American labor history.

Precipitated by a lockout and strike, the Battle of Homestead proved the lengths that workers would go to in order to defend their livelihood, and the lengths to which owners would go to retain absolute control of their company. During and after the conflict the participants involved would find themselves thrust into the national spotlight: the Carnegie Steel Company, its leadership in the form of Andrew Carnegie and Henry Clay Frick, the Amalgamated Association of Iron and Steel Workers, the townspeople of Homestead, the Pinkerton National Detective Agency, and, eventually, the Pennsylvania Militia sent to occupy the town. Their actions during this crucial period would ripple across the American labor movement for decades to come.

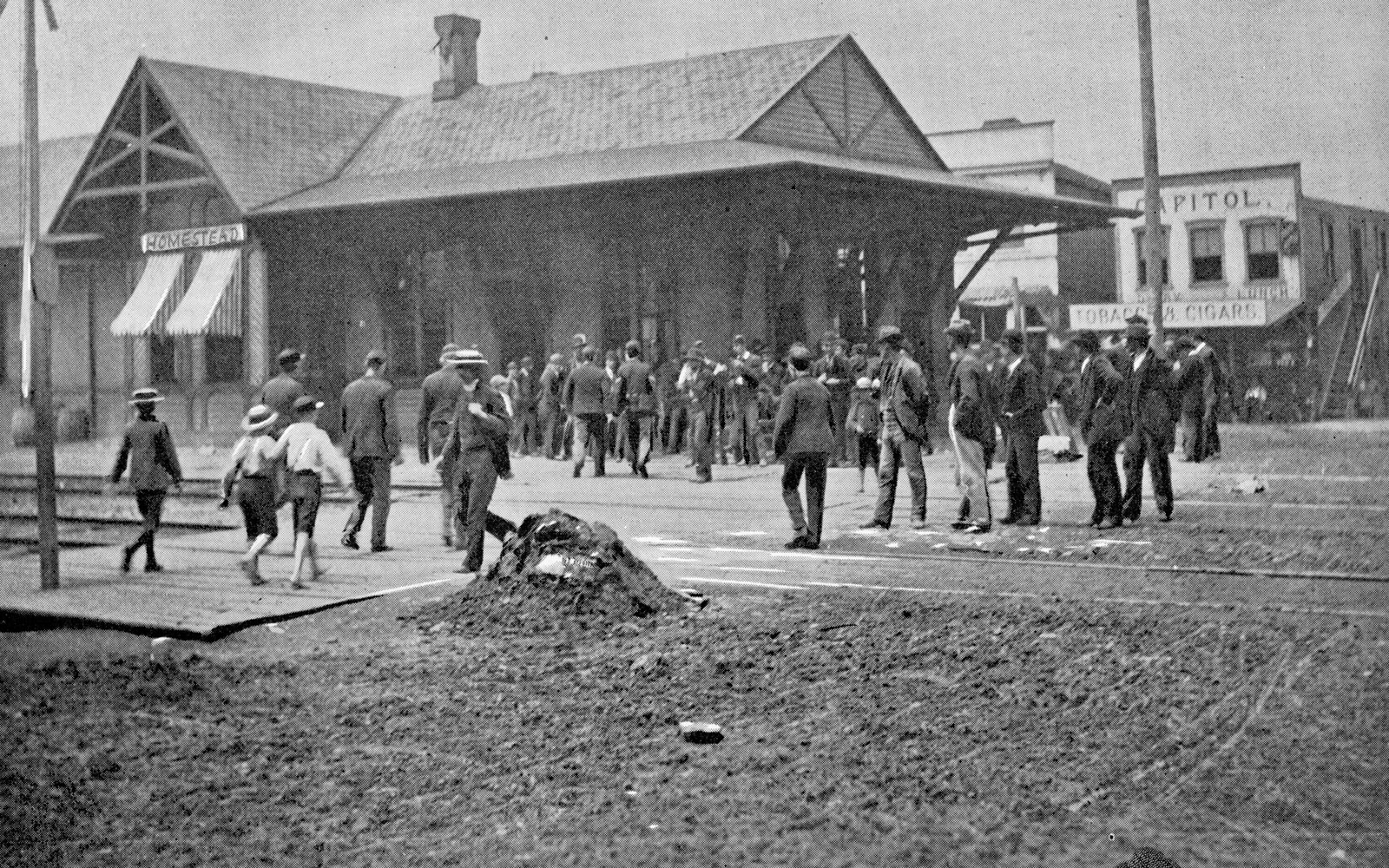

Homestead: Soldiers ordering strikers away from the railroad station

Tensions Build

Labor Vs. Management: The Balance of Power

Tension between Carnegie Steel and the union escalated in the early 1880s, and did not diminish after the Amalgamated Association of Iron and Steelworkers (AAISW) made significant gains with a successful strike at Homestead in 1889. Following this strike, the balance of power shifted toward the workers, with company leaders begrudgingly admitting that the bylaws in the union’s contract essentially dictated work rules and production. While Carnegie publicly accepted the presence of unions, he privately conspired with Henry Clay Frick to reduce the Amalgamated’s power in Homestead.

Labor Vs. Management: The Balance of Power

With the collective bargaining agreement due to expire June 30, 1892, Frick and the AA entered into negotiations in February. The AAISW, which represented about 300 skilled workers in the plant, sought wage changes and protections for their jobs, which they felt, were potentially threatened by an influx of unskilled labor and encroachment of technological advances. In particular, they looked to maintain a high wage tied into total tonnage of steel produced. Frick responded by proposing sweeping cuts to wages—based upon the ideal of the sliding scale, where wages were tied to the price of steel on the open market—and union positions at the mill.

Fort Frick: The Lockout & Strike

Negotiations broke down as Frick purposefully refused to grant meaningful concessions in hopes of forcing a conflict, and in late June Frick locked the union out of the mill. In anticipation of the events, Frick had the mill property fortified with barbed wire fence, water cannons, and sniper towers in a structure that came to be popularly known as Fort Frick. In return, the now striking workers vowed to keep the mill closed, and posted men outside to prevent people from entering.

Frick’s attempts to use scab (black sheep) labor to break the strike failed as the union, with the aid of the people of Homestead, had established patrols and town wide rules to limit access by outsiders and run off any strikebreakers.

Access to “Fort Frick” was cut off, unable to be opened even by Homestead’s sheriff, who was rebuffed by the strikers. Unwilling to negotiate further or wait for outside aid, Frick hired the services of the Pinkerton Detective Agency and arranged for 300 armed Pinkertons to cordon off the mill, and reopen it.

July 6 1892: The Battle of Homestead

The Pinkertons Are Coming

On the morning of July 6, the Pinkerton agent set sail from Davis Island on the Ohio River and headed down the Monongahela River towards Homestead. The goal was to dock on mill property so that any interference by the striking workers would be considered illegal trespass. The barges and their tugboat, the “Little Bill,” docked at the river’s edge below the main pumping station for the mill. The Amalgamated had sentries tracking the barges movement towards the mill. As word spread that the Pinkertons were coming, thousands of striking workers and their supporters broke through the fences at the mill and met the barges at the dock.

Violence Erupts

No one knows who fired the first shot, however fighting broke out, with men firing on both sides. The Pinkertons were unable to come ashore. The skirmishes continued throughout the day leaving 7 strikers and 3 Pinkertons dead, and dozens of people injured. By late afternoon the Pinkertons negotiated surrender. The strikers and townspeople, who had gathered in an angry crowd, looted the barges and burned them.

The Bloody Gauntlet

Despite the pleas of William Weihe, the AA president, the town and strikers did not allow the Pinkertons to surrender peacefully, and forced the captured detectives to run a “Bloody Gauntlet” that saw the Pinkertons assaulted. The Pinkertons were taken to the Homestead Opera House and then shipped out of town by rail the following morning. This treatment shocked many reporting on the event for the media, and began to turn sympathies away from the strikers.

The Lockout & Strikes Continues

The Militia Arrive

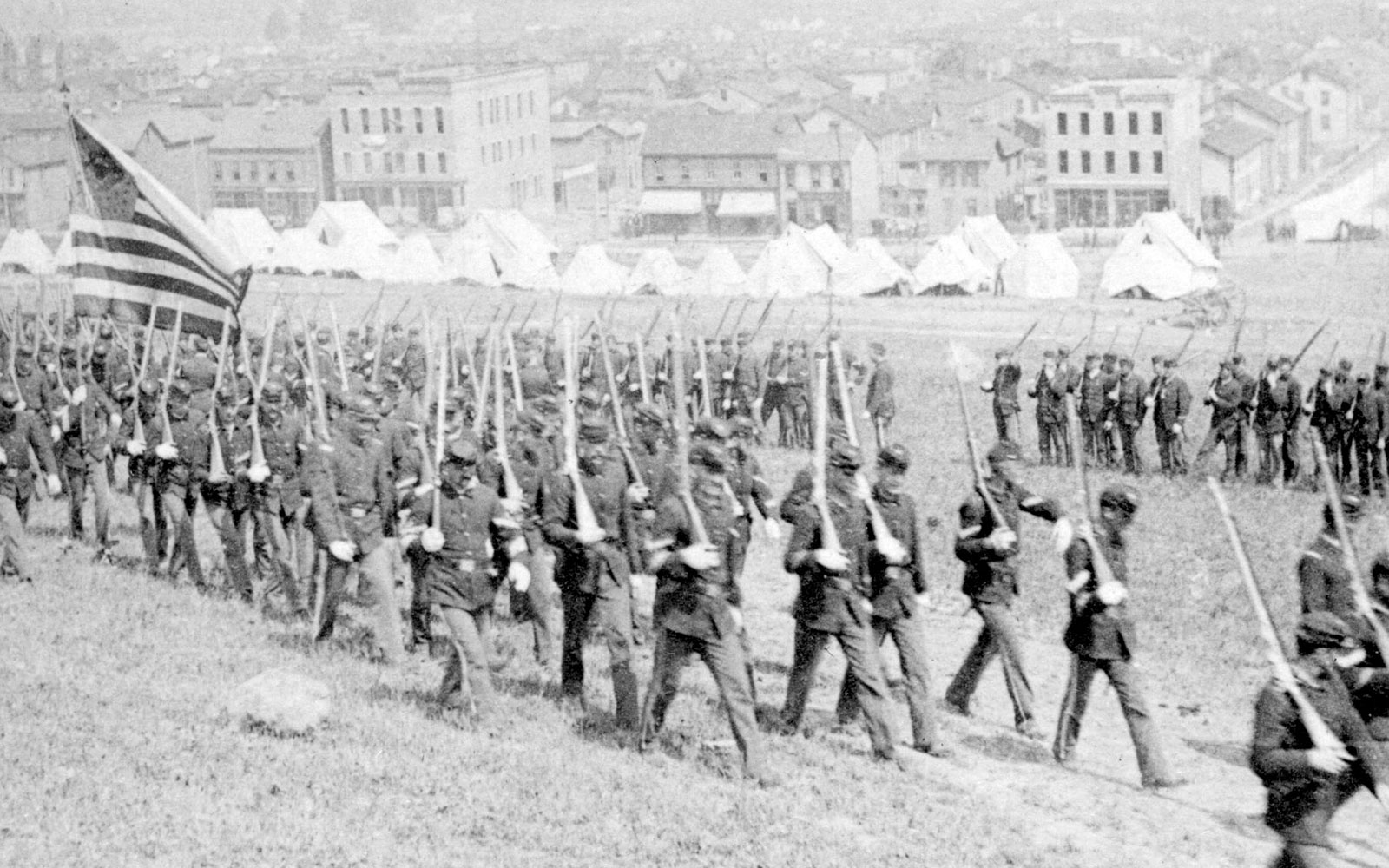

On July 12, the National Guard in the form of several thousand members of the Pennsylvania State Militia arrived in Homestead, having been mustered some days earlier and quietly sent to the town by train at an opportune time. Despite attempts by the strikers to welcome the Guard and convince them of the legitimacy of their cause, the commanding officers, under orders from the governor, sided with ownership and quickly dispersed the men surrounding the mill.

The Occupation Begins

They established a camp overlooking the town, began to guard Homestead and the mill, and reopened the works for Frick’s strikebreakers, who were housed on the grounds at great expense. Still, the strike continued, neither side willing to come to the table despite their increasingly precarious positions.

An Assassination Attempt

With both sides now pressured to find a permanent solution, something unexpected happened: an anarchist by the name of Alexander Berkman shot Frick in an unsuccessful assassination attempt. Though Berkman was unassociated with the strikers, his actions turned the public’s opinion further against the union, and precipitated the collapse of strike.

The Strike is Broken

With little other recourse, the strikers were forced to go back to work under Carnegie’s terms, a complete defeat. Three hundred of the striking men were blacklisted for life, never again able to work within the industry.

The Aftermath

Even with the end of the strike and, eventually, the occupation, there were many matters yet to be settled. Lawsuits, civil and criminal, were filed against both the strikers and the ownership. Hearings were held within the state government, looking at both the actions of the strikers and particularly the decision to hire the Pinkertons as a mercenary force, with legislation passed to prevent the Pinkertons from being used as such in the future. Most importantly, the capitulation of the union led to the elimination of unions in the industry until the formation of SWOC in the late 1930s, resulting in a nearly 40-year gap of non-union labor in steel and iron.

One of five Rivers of Steel attractions

that showcase the artistry and innovation of our region’s rich heritage.