A CSX train approaches Station Square, August 2020.

By Brianna Horan, Manager of Tourism & Visitor Experience

Exploring the Rivers of Steel National Heritage Area – Trains & Tracks!

Exploring the Rivers of Steel National Heritage Area – Trains & Tracks!

Transforming Travel & Industry

Railroads and streetcars were once vital to the movement of people, natural resources and manufactured goods throughout southwestern Pennsylvania to power the Big Steel industry. The first tracks were laid here in the 1840s, but it was in the 1870s that railroad networks spread throughout the region, crisscrossing what is today the Rivers of Steel National Heritage Area. To get people to their jobs, streetcar lines reached into every neighborhood in major towns, and Interurban lines connected mine patches and market towns with each other and with Pittsburgh. Long-distance mainlines—like the Pennsylvania Railroad, the Baltimore & Ohio, the Norfolk & Western, the Pittsburgh & Lake Erie, and the Bessemer & Lake Erie—carried raw materials, products, produce, and people between southwestern Pennsylvania and the rest of the nation. Steel companies built rail spurs to carry coke fuel from their mines to riverfront barge landings, and workers from one plant or patch to another. And that’s not even counting the hundreds of miles of train tracks on mill sites themselves to move materials and molten iron between shops—there were more than 150 miles of track within U.S. Steel’s Homestead Works alone.

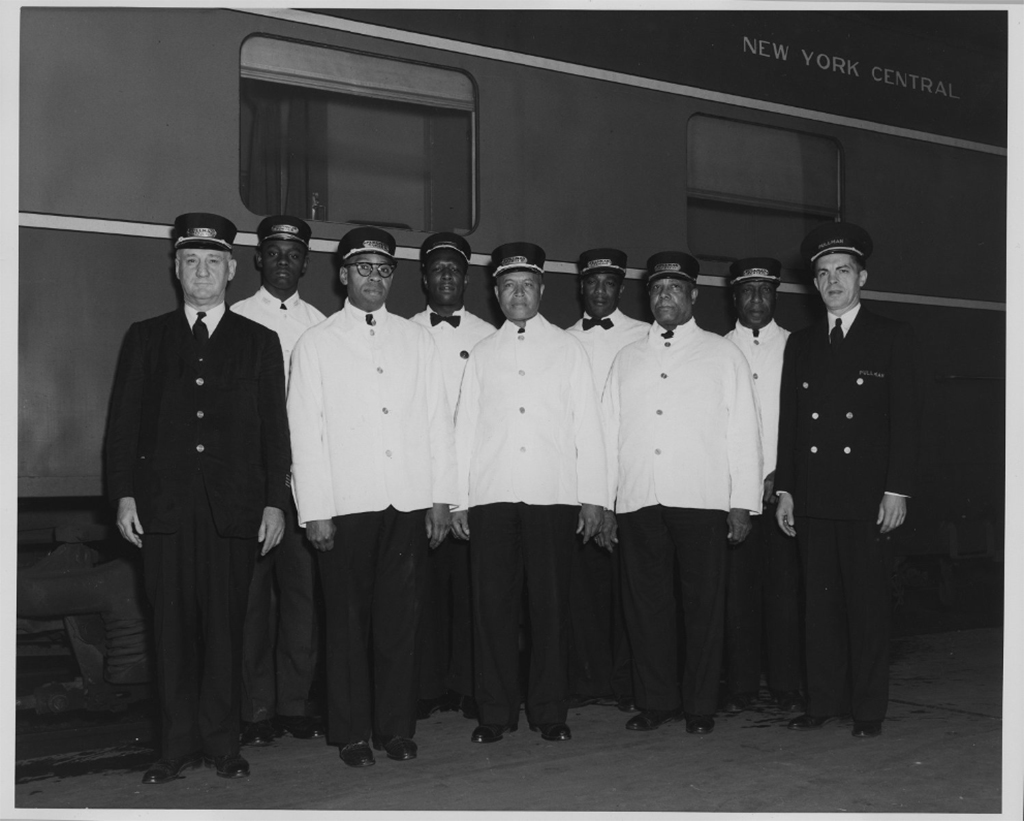

Pittsburgh and Lake Erie Railroad Pullman porters, steward and conductor standing in front of a New York Central Railroad car, September 8, 1950. Courtesy of the University of Pittsburgh via Historic Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh and Lake Erie Railroad Company Records Collection.

The Complicated (and Even Subversive) Legacy of Pullman Porters

Many physical remnants of tracks and rails exist to visit throughout the region today, whether preserved as a museum or historic site, repurposed into a new dining or entertainment venue, or still moving people and things from one place to another. But as time passes, memories of the height of train travel dwindle and become even more valuable. This 2009 article from the Pittsburgh Tribune-Review captures recollections of former KDKA-TV reporter Harold Hayes and the late Harvey Adams Jr., a prominent civil rights leader who helped integrate the Pittsburgh police force, both of whom were grandsons of Pullman porters. This 2002 article from the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette shares more locals’ memories of the pride that porters took in their work, and the racist treatment they endured from passengers and their employers.

The legacy of Pullman porters has ties in cities across the United States. To bring luxury and convenience to the rising railroad industry after the Civil War, industrialist George Pullman furnished plush sleeper cars that included the service of a porter. Pullman hired only African-American men—often former slaves—for this role, who were expected to be at the beck and call of the passengers they served. Common duties included carrying luggage, shining shoes, ironing clothing, minding children, tidying the train car, and serving food—some passengers even expected porters to entertain them with song and dance. “When Lincoln freed the slaves, George Pullman hired them,” is a saying often associated with Pullman porters.

Harvey Adams Jr. told the Tribune-Review that with all of the work to be done, his grandfather, Wister Adams, “walked” to California and back on the cross-country trains that he worked on for decades. With trains traveling across the country at all hours of the day, porters also had grueling schedules. They generally worked 400 hours each month, and usually were allowed only three or four hours of sleep between their 20-hour daily shifts. Porters had to pay for their own meals, and the purchase and care of their uniforms was also their responsibility.

Margaret Tardy, a Cincinnati resident, told the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette in 2002 that she remembered her father, Harold T. Tardy Sr. of East Liberty, proudly wearing a black uniform and white shirt with a starched collar, topped by a black cap with a small bill. She said her father, who passed away in 1964, liked to go to baseball games in New York City when he had time off, and that he avoided traveling below the Mason-Dixon line to the Jim Crow South. For generations, porters were all addressed by passengers as “George”—after George Pullman, just as slaves were called by their master’s name before emancipation. Margaret remembered that her father, who was a member of the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters, rejected that treatment. She told the Post-Gazette, “Dad would point to his name tag, greet the passenger with a smile and respond that he had a name, and his name was Harold.”

View of a porter posing in a new side-door Pullman dining car, May 22, 1935. Courtesy of the University of Pittsburgh via Historic Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh and Lake Erie Railroad Company Records Collection.

Life as a Pullman porter was demanding and often demeaning, while also allowing Black men to bring decent wages home to their families and information from other parts of the country to their communities. Harold Hayes told the Tribune-Review that his grandfather, Thomas Burrell, earned $3,200 in wages and $700 in tips in 1950, an income that allowed him to build a house in Beltzhoover and send his daughter to Howard University. Burrell worked on the Pittsburgh to Detroit run on the Pennsylvania Railroad for 13 years.

In 2002, a 77-year old James Austin of Homewood reminisced to the Post-Gazette about visits uncle, Spurgeon “Sonny” Austin, would make to his childhood home, preferring to stay with family instead of at a boarding home in the Strip District like many Pullman porters did. James remembered his uncle sharing dozens of stories from his travels, and that he “could make a bed faster than anyone in the house.”

Pullman porters were key in expanding the reach of the Pittsburgh Courier, one of the most widely circulated and well-respected Black newspaper in the country in the 1930s and ’40s. At that time, sheriffs in the Jim Crow South banned the publication and frequently burned those that made it into their towns. To get the paper into the South, the Courier launched a clandestine distribution campaign in 1936 that lasted until the mid-1940s. The Post-Gazette reported that porters helped to deliver 100,000 papers a week into the south.

The elaborate operation started when the Courier camouflaged its trucks and smuggled bundles of papers to the railroad station in Pittsburgh, wrapped in special weather-proof paper. Porters hid them aboard or under the trains, and then dropped the bundles off about two miles outside major cities like Chattanooga, TN; Mobile, AL; and Jacksonville, FL. A network of Black ministers would then secretly retrieve the papers and distribute them to their congregations.

Porters distributed the papers for free, but sometimes received as tip from the Courier. The success of these secret deliveries led other Black newspapers to turn to the porter network to distribute their papers in the South, as well. Frank Bolden, a former city editor and foreign correspondent for the Courier, told the Post-Gazette in 2002, “They were the guys on the front lines. They were foot soldiers.”

A contemporary image of the front facade of the Wilkinsburg train station. Courtesy of the Wilkinsburg Community Development Corporation.

Rail-related Destinations in the Heritage Area

If you’re planning to hit the road on these itineraries during the global pandemic, please be mindful of the health and safety guidelines in place from the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Be sure to contact the sites, restaurants and attractions directly to confirm their operating statues and the safety protocols they have in place. We encourage you to bookmark these itineraries as travel inspiration to return to when things are less uncertain.

Carnegie Science Center Miniature Railroad, courtesy of the Carnegie Science Center.

Carnegie Science Center’s Miniature Railroad & Village

One Allegheny Ave., Pittsburgh, PA 15212 | 412-237-3400 | carnegiesciencecenter.org

For more than 100 years, this miniature replica of regional landmarks has captivated visitors with scenes of the way people in the Pittsburgh area lived in an era spanning the 1880s to the 1940s. This detailed, animated display started in the home of Charles Bowdish of Brookville, PA, in 1919; it was moved to the Buhl Planetarium in 1954, and then opened at the Carnegie Science Center in 1992. The 83-foot by 30-foot platform usually has about five trains and one trolley operating on a landscape that includes key historic and cultural sites like Kaufmann’s Grand Depot, Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood House, Fallingwater, Punxsutawney Phil, and many more.

DiSalvos Station, Latrobe by Deborah Stofko.

DiSalvo’s Station Restaurant

325 McKinley Ave., Latrobe, PA 15650 | 724-539-0500 | disalvosrestaurant.com

This restored 1903 train depot of the former Pennsylvania Railroad Station in Latrobe serves classic Italian fare that has earned numerous accolades. Guests enter the restaurant by walking through a tunnel that leads to a spacious, cobblestone atrium. A full-sized dining car sits inside the restaurant, and the former luggage and ticketing area is now a tap room. The lower level of the restaurant is a cavernous, speakeasy-style cigar bar.

Pittsburgh from Mt. Washington with Duquesne Incline Station. Photo by Richard Nowitz.

Duquesne Incline

Lower station parking lot 1197 W. Carson St., Pittsburgh, PA 15219 | 412-381-1665 | DuquesneIncline.org

The 794-foot long double tracks of the Duquesne Incline have been lifting passengers in twin cars a height of 400 feet up and down the face of Mount Washington since 1877, closely following the path of an earlier coal hoist. At one time there were nearly 20 funiculars servicing Pittsburgh’s bluffs, carrying cargo, livestock, and people. But today the Duquesne Incline is one of the few remaining in the country—along with the Monongahela Incline further east on the face of Mount Washington. Be sure to take a tour below the operator’s room at the Duquesne Incline’s upper station to see the hoisting equipment in action!

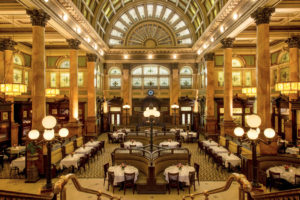

Grand Concourse Restaurant and Station Square

100 W Station Square Dr., Pittsburgh, PA 15219 | 412-261-1717 | GrandConcourseRestaurant.com

At the base of Mount Washington lies a dining and entertainment complex along the Monongahela River called Station Square. This area is where passengers once arrived on the Pittsburgh & Lake Erie Railroad, first chartered in 1877. It soon became known as the Little Giant for the amount of tonnage that it moved through the region. Shops, restaurants and nightlife now make their homes in the terminal and freight station; the historic Pittsburgh Terminal Train Station has been preserved as a multi-purpose building. The ground floor houses Grand Concourse restaurant, a local favorite for more than 40 years, resplendent with stained glass, intricate woodworking, a grand staircase, and many reminders of the building’s past life.

At the base of Mount Washington lies a dining and entertainment complex along the Monongahela River called Station Square. This area is where passengers once arrived on the Pittsburgh & Lake Erie Railroad, first chartered in 1877. It soon became known as the Little Giant for the amount of tonnage that it moved through the region. Shops, restaurants and nightlife now make their homes in the terminal and freight station; the historic Pittsburgh Terminal Train Station has been preserved as a multi-purpose building. The ground floor houses Grand Concourse restaurant, a local favorite for more than 40 years, resplendent with stained glass, intricate woodworking, a grand staircase, and many reminders of the building’s past life.

Harry Clark’s Indian Creek Valley Railroad Model Railroad at Connellsville Canteen

131 West Crawford Ave., Connellsville, PA 15425 | 724-603-2093 | connellsvillecanteen.org/harry-clark

Image courtesy of the Laurel Highlands Visitors Bureau.

All aboard to the Connellsville Canteen, home to a local World War II museum, a charming café, and a world-renowned model railroad display. After returning from World War II, Connellsville native Harry Clark started to build train cars by hand at the kitchen table as a way of relaxing. Clark came from a long line of B&O Railroad employees, and was a carpenter by trade. Over fifty years, he built what became a world-renowned display that he called the Indian Creek Valley Railroad, depicting Connellsville, Meyersdale, and other mountain towns in western Pennsylvania from the 1940s and ’50s in loving detail. Nearly all of the buildings, train cars, stations, saw mills, patch towns, coal mines and coke ovens were made by hand. In 2012, about a year after Clark’s death at age 91, the display was moved in one 28,000-pound piece on a tractor trailer from Nemacolin Woodlands Resort, where it was formerly showcased, to its new home. A crane lifted the 25-foot by 50-foot model railroad in place, and the Connellsville Canteen was built around it, modeled after the town’s old B&O station. Clark’s display was featured in Model Railroader Magazine with a centerfold, and Model Railroad Academy produced a nine-part video series about the Indian Creek Valley Railroad display and Clark’s passion and talent – a great way to enjoy the display virtually!

Thomas Town at Kennywood, courtesy of Kennywood.

Kennywood Park

4800 Kennywood Blvd., West Mifflin, PA 15122 | 412-461-0500 | kennywood.com

This historic, beloved amusement park in West Mifflin has tracks galore – on rickety wooden coasters, adrenaline-packed steel coasters, and retro favorites like The Turtles or the Auto Race. Younger railroad enthusiasts will delight with a visit to the park’s Thomas Town, with a number of kiddie rides and a Thomas-themed train ride that guests of all ages will enjoy.

Ligonier Valley Rail Road Association

3032 Idlewild Hill Lane, Ligonier, PA 15658 | 724-238-7819 | lvrra.org

The Ligonier Valley Rail Road’s 10.3-mile long main line connected Ligonier and Latrobe—a relatively short amount of track that was a long time coming. It took about 25 years of planning, surveying, and legislating before Judge Thomas Mellon finally stepped in and agreed to complete and operate the railroad line in 1877. His main goal for the venture was to give his sons, Andrew and Richard, business experience. Idle Park, or Idlewild, was a venture established by the Mellons to increase passengers on their train, but the real boon for business was hauling freight – coal, coke, stone, and lumber. The “Liggie” made its last run in 1952 after 75 years of operation, but today the Ligonier Valley Rail Road Museum keeps the line’s history alive in an original station that was built around 1896.

Open car at Museum Road, courtesy of Trolley Museum.

Pennsylvania Trolley Museum

1 Museum Rd., Washington, PA 15301 | 724-228-9256 | pa-trolley.org

Step back to the dawn of the Electric Age when in 1918 the Pittsburgh Railways Company operated some 2,000 trolley cars, 65 different lines, and more than 600 miles of track. A nickel would take you where you wanted to go! After enduring hard times during the Great Depression, streetcars were returned to service during World War II when fuel and rubber were rationed. But after the war, the rise of the suburbs and the auto culture spelled out the end of the trolley’s heyday. Lucky for us, staff and volunteers at the Pennsylvania Trolley Museum in Washington have been preserving the nostalgia, history, and streetcars of this era since 1949. Visitors can step aboard and see the restoration in progress of more nearly 50 cars including the original “Streetcar Named Desire,” take a roundtrip ride on a vintage trolley, and engage with hands-on exhibits that even put them behind the controls of a street car.

A restored streetcar is in the History Center’s Great Hall. Courtesy of Senator John Heinz History Center.

Senator John Heinz History Center

1212 Smallman St., Pittsburgh, PA 15222 | 412-454-6000 | heinzhistorycenter.org

There are a number of transportation-themed exhibits to explore at the Heinz History Center in Pittsburgh’s Strip District. Pittsburgh Streetcar #1724 greets you upon arrival into the museum’s Great Hall, where you can step onboard and imagine what it would have been like to travel through the South Hills communities on this streetcar – as it did until 1988. Visit the History Center’s Pittsburgh: A Tradition of Innovation exhibit to see pieces of the extensive Westinghouse Collection. George Westinghouse’s influence on the world was wide ranging, including the invention of the air brake, automobile shock absorbers, the development of railroad signaling, and much more. After your visit, you can also take a ride by the nearby Pittsburgh Opera Headquarters on Liberty Ave. between 24th and 25th Sts., which was built in 1869 as Westinghouse’s original air brake factory.

Youngwood Railroad Museum and Station Cafe

1 Depot St., Youngwood, PA 15697 | 724-925-7355 | facebook.com/YoungwoodRRMuseum/

Home to an assortment of locomotive paraphernalia, photographs, uniforms, equipment, and miniature train collections, this museum opened in Youngwood’s depot building the same year it was set to be demolished, 1982. Concerned citizens and railroad enthusiasts couldn’t let the legacy of their town’s rich railroad industry be forgotten. The original train crossing was established in the 1870s at the junction of John Young’s and James Woods’ properties, and by 1902 the newly chartered borough of Youngwood boasted a 15-bay roundhouse, a switch tower, miles of mainline and spur tracks, and the depot building, home to the Pennsylvania Railroad’s baggage and passenger station. Twenty years later, one-seventh of the nation’s supply of coal and coke ran through the Youngwood yard, which sometimes saw as many as 700 train cars per day.

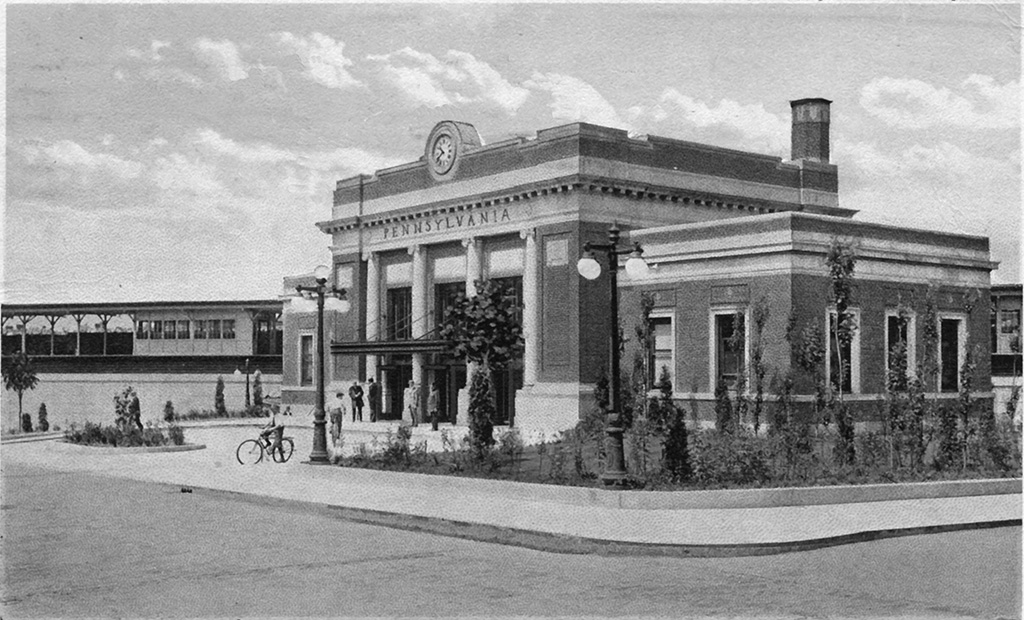

Wilkinsburg Train Station 1916, courtesy of the Wilkinsburg Community Development Corporation.

Coming Soon: The Wilkinsburg Train Station Restoration Project

Across the street from Wilkinsburg Public Library, 605 Ross Ave., Pittsburgh, PA 15221

After sitting vacant for more than 50 years, this beaux-arts beauty is being lovingly restored to its original glory and is set to once again become a hub of community activity in the revitalizing town of Wilkinsburg. Originally built in 1915, the opulent station earned a spot on the National Register of Historic Places in 1985. When the $6.5 million renovation is complete, it is intended to be a center for indoor and outdoor dining, shopping, and community gatherings.

Holiday Displays

A number of local model railroad collectors open only during the holiday season to showcase the miniature scenes and tracks that their members lovingly preserve and create. Visit their websites for more information:

- Western Pennsylvania Model Railroad Museum in Gibsonia | wpmrm.org

- Ohio Valley Lines Model Railroad in Ambridge | ohiovalleylines.org

- McKeesport Model Railroad | mckeesportmodelrr.com

- Allegheny West Toy Train Museum in Pittsburgh’s North Side| tinyurl.com/yc7cyaac

- Beaver County Model Railroad and Historical Society in Monaca | bcmrr.railfan.net

If you missed it check out the Automobiles and Roadways itineraries, part one and part two.

Stay tuned for more itineraries through the Rivers of Steel National Heritage Area, as we continue to explore the region through the lens of transportation.

Exploring the Rivers of Steel National Heritage Area – Trains & Tracks!

Exploring the Rivers of Steel National Heritage Area – Trains & Tracks!