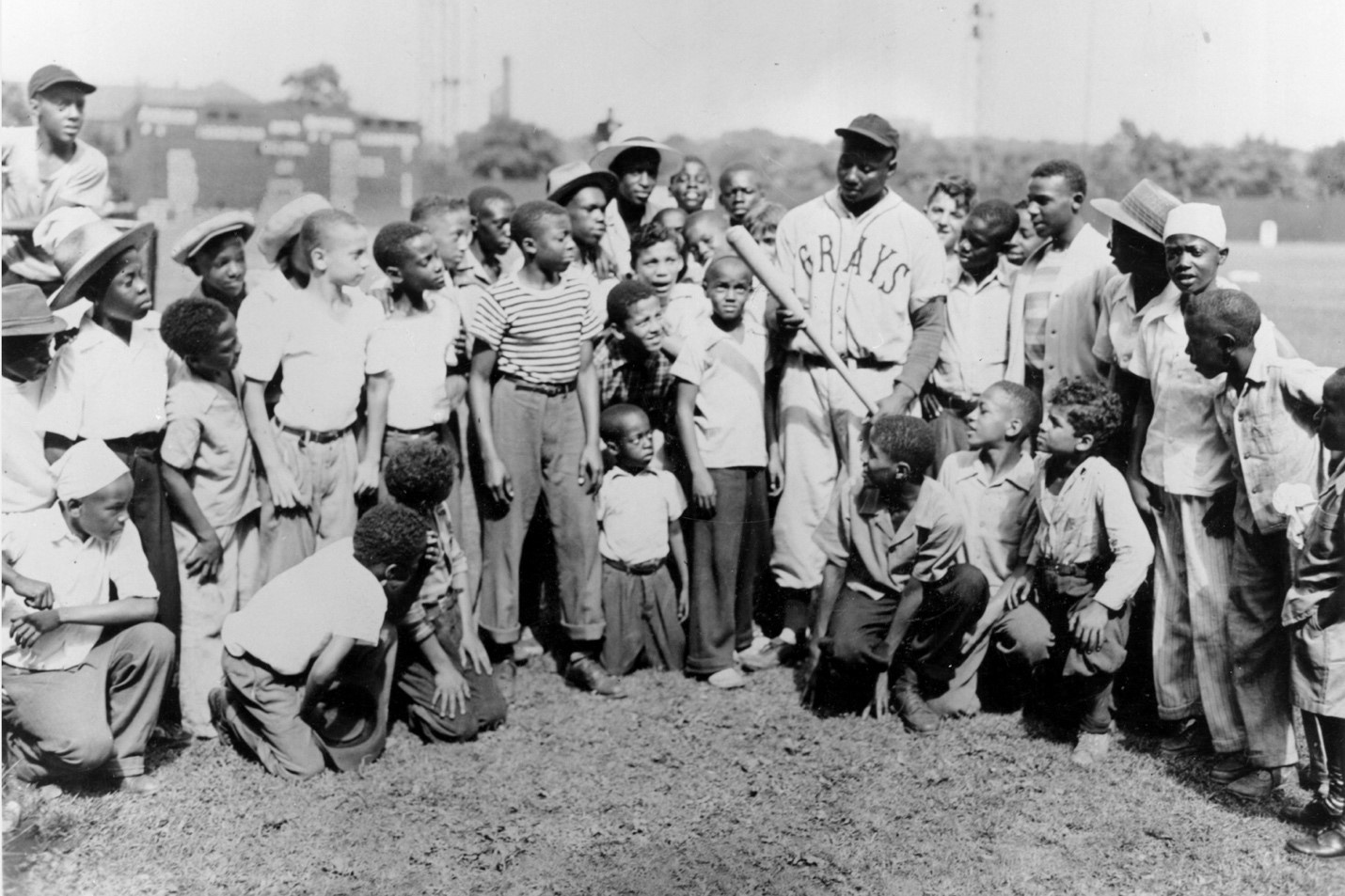

By Ron Baraff, Director of Historic Resources and Facilities | Image of the Josh Gibson with young ballplayers.

That Gibson Fellow…

That Gibson Fellow…

“There is a catcher that any big-league club would like to buy for $200,000. His name is Gibson. He can do everything. He hits the ball a mile. He catches so easy he might as well be in a rocking chair. Throws like a rifle. Too bad this Gibson is a colored fellow.” – Hall of Fame pitcher Walter Johnson

Tucked uncomfortably in the consciousness of America and Baseball is the image of one Josh Gibson. Staring up at us as a culture, reminding us that the greatest among us are not always the most well-known, cared for, fairly treated, or respected in their mortal lives. A giant among men, a ballplayer’s ballplayer, a textbook catcher, hitter, thrower, and runner, Josh was a five-tool player forced to live in a time when his many talents could not be on full display for all to see.

Such was the life of a ballplayer of color, from the dawn of the so-called “Gentleman’s Agreement” in 1888 through the breaking of the color barrier in 1947 by Jackie Robinson and the Brooklyn Dodgers. Life was tough; the playing field was not even close to being level. However, there existed a parallel universe in the Negro Leagues—one where men of color could play the great game of baseball, “America’s Pastime”, and achieve heights never imagined or seen since. These men played under the direst of circumstances, denied not just full rights as ballplayers to play on the biggest stage in organized “Major League Baseball” (MLB)— i.e.: White Baseball—but also as citizens. They had to struggle to make gate, live respectfully, and travel and survive in a time when much of the world was closed to them.

Through this darkness shone some amazingly bright, brave, talented, and everlasting lights. Among them were Satch, Cool Papa, Buck, Ray, and Josh, playing ball at such a level in Pittsburgh for the Crawfords, and in Homestead for the Grays, that their names and exploits became legendary.

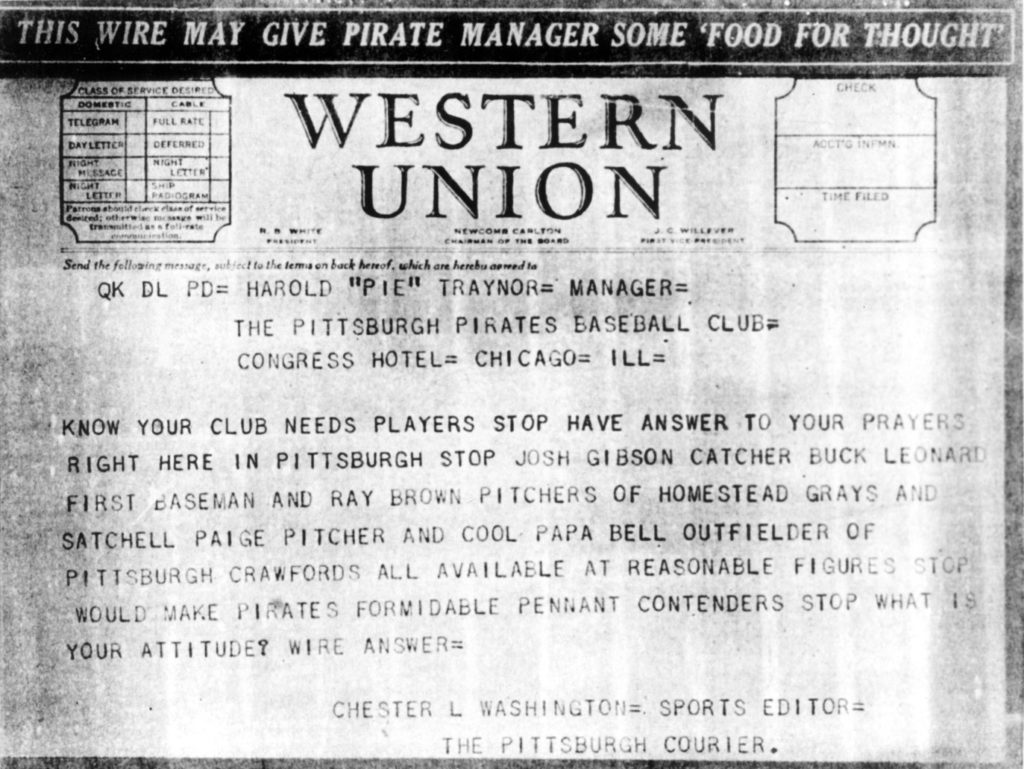

In 1938, prominent sports editor and later publisher of the great African American newspaper The Pittsburgh Courier, Chester L. Washington, sent a telegram to Pittsburgh Pirates player / manager Harold “Pie” Traynor. This telegram (see below) is an amazing slice of sporting and cultural life—a “what if…” scenario that unfortunately never came to be. It offered the Pirates the opportunity to be in the vanguard of sport, society, race relations, and even the chance to perhaps be remembered as the greatest team (dare I say dynasty?) ever assembled. The 1938 Pirates were a strong team, anchored by future Hall of Fame players Arky Vaughan (SS), Paul Waner (RF), Lloyd Waner (CF), and Pie Traynor (3B). They were in the pennant race until the end of the season, finishing at 86-64, a mere two games behind the pennant-winning Chicago Cubs. What they were lacking was dominant pitching (Satchel Paige and Ray Brown), a strong catcher (Josh Gibson), speed (Cool Papa Bell), and a middle of the order bat (Buck Leonard).

From all reports, Pie Traynor was very open minded about integration. He was quoted in a 1939 interview with the Courier as saying, “Personally, I don’t see why the ban against Negro players exists at all.” He was especially open to it if it improved his club’s fortunes on the diamond. Sadly, the Pirates never responded to the telegram. Why? Perhaps it was fear of retribution from the other clubs in the “Majors”, or maybe it was the knowledge that baseball czar Commissioner Kennesaw Mountain Landis was openly racist and had blocked other attempts at integration—and would likely step in and do so again.

A copy of a telegram sent by The Pittsburgh Courier’s sports editor Chester L. Washington to the Pittsburgh Pirates proposing they hire legendary Negro League players to strengthen the team and spark integration in baseball. The 1938 Pirates never responded to this telegram.

Baseball would stay segregated for almost another decade until Jackie Robinson broke the color line in 1947 with the Brooklyn Dodgers. Over the next 12 years, MLB teams would slowly integrate their teams. The Pirates joined the parade 16 years after Chester Washington’s telegram, when Curt Roberts made his debut at second base on April 13, 1954. By the late 1950s, the last vestiges of the Negro Leagues disappeared from the sporting landscape. Along with their demise came calls to recognize the greatness of their play, their culture, and sporting significance. The men (and even some women…we will save that for another article…) who gave everything they had to their sport needed to be recognized, acknowledged, and accepted as the equals (at the very least) of those who played Major League Baseball during the dark years of the Gentlemen’s Agreement.

Finally, in 1971, Satchel Paige became the first player who spent the majority of his career in the Negro Leagues to be enshrined in the Baseball Hall of Fame. Josh Gibson followed in 1972. However, these men and their compatriots still didn’t have an equal place among the Major Leagues until December of 2020, when the MLB officially recognized the seven professional Negro Leagues that operated between 1920 and 1948. This long overdue decision means that the 3,400 +/- players from the Negro Leagues during this time period are officially considered Major Leaguers, with their stats and records becoming a part of Major League history.

The accompanying photograph and copy of the infamous telegram are housed in the Rivers of Steel Archives as part of the Josh Gibson Foundation Collection. Rivers of Steel has partnered with Sean Gibson, great-grandson of Josh Gibson and Executive Director of the Josh Gibson Foundation, to serve as the repository for their collection.

If you like this story, you may want to read The Lasting Legacy of Cap Posey. Cumberland “Cap” Willis Posey was a black man who established himself as a titan of industry on the Monongahela River in the 1800s and his son, Cum Posey, became the not just a ballplayer for the Homestead Grays, but its principal owner, among other accolades.

That Gibson Fellow…

That Gibson Fellow…