Entrance to the Greensboro Pennsylvania Art Cooperative’s ceramic studio.

Heritage Highlights

Rivers of Steel’s Heritage Arts program strives to represent the region’s diverse cultural heritage, from ethnic customs and occupational traditions directly linked to Pittsburgh’s industrial past to new American folk arts and cultural practices emerging from the region’s diverse urban experience. Usually passed down from person to person within close-knit communities, these cultural traditions are as varied as they are unique, each representing one aspect of what makes southwestern Pennsylvania’s heritage so rich.

This month, we continue our exploration of southwestern Pennsylvania’s small towns. Heritage Arts Coordinator Jon Engel spoke with Shane McManus, founder of the Greensboro Pennsylvania Art Cooperative. The Cooperative is a group of artists working out of the historical Davis Theatre in Greensboro, a Monongahela River town just a few miles upriver from the West Virginia border. Providing studio and commercial space for its artists, the co-op model splits profits between members and the organization as a whole. Shane himself is a life-long resident of Appalachia, a folk artist, and a musician. Jon and Shane discussed the Cooperative’s guiding philosophy and how it interacts with the things that make Greensboro unique.

Greensboro Pennsylvania Art Cooperative

By Jonathan Engel

By Jonathan Engel

“In Greensboro,” says Shane McManus, “it’s really hard to throw a shovel into the ground without finding something historic.”

We spoke over the phone this summer about his work with the Greensboro Pennsylvania Art Cooperative, an artists’ group and studio that he founded. Shane and the other members have become something like DIY archaeologists over the years. Guided by aged maps of the town’s 19th century ceramics industries, they have explored the Cooperative’s historic property with boots and shovels. In doing so, they discovered the foundational bricks of a 200-year-old kiln, still in the same spot that the town’s earliest potters built their businesses. Artifacts like these abound in Greensboro, with many of them on display at the Antique & Oddity Café, a local shop next to the Cooperative’s Front Street studio space.

Greensboro Origins

Greensboro is a small town, but a storied one. It was one of the first areas of southwestern Pennsylvania to be colonized. Before this, it was populated by a group of Iroquois, also know as Haudenosaunee, tribespeople, who—the current locals say—named this area “Delight” for its excellent soil and flat, riverside land. Sometime in the 1780s, a Virginian man named Elias Stone acquired it and delineated it into the street plan that stands today. On February 2, 1790, Stone’s new village was officially recognized as “Greensburgh,” named for the Revolutionary War general Nathanael Greene. It would keep that name until 1879, when it became Greensboro.

The new town quickly found its niche as a home to industry. In 1795, a businessman named Albert Gallatin met some German glassblowers who were traveling out west to start anew in the recently created state of Kentucky. Somehow, Gallatin convinced them to move to New Geneva, Pennsylvania instead—right across the Mon River from Greensboro—and start a company there, producing high-quality “New Geneva glass,” which became famous across the nation. The factory moved to Greensboro ten years later.

From then on, like most of the Mon Valley, Greensboro lived and died by the boom-and-bust cycles of the manufacturing industry. The old glassworks factory closed in 1849. By then, Greensboro was home to several successful redware potters, who created basic pottery in small shops. Then, in the mid-1800s, they were replaced by two large ceramics companies, who used local clay to produce more durable stoneware. This became Greensboro’s main export.

For a while, Greensboro was the gateway to Pennsylvania trade, attracting up to 500 residents to this .11 square mile town, which consists of about a dozen blocks and a dock. Then in 1880s more efficient potters began to outcompete the James Hamilton Company. Their manufacturing economy suffered further when engineering changes to the Mon River shifted trade traffic toward Morgantown. Tides turned again in the early the 1900s as Greensboro became a cultural hub for the Valley’s network of coal settlements, a place where the miners could come to church and enjoy a night on the town. This lasted until the local coal industry collapsed in the 1930s, and, again, the local economy went with it.

These familiar trends have left a vast weight of history, metaphorically and literally, on Greensboro.

Promoting the Past; Sustaining the Future

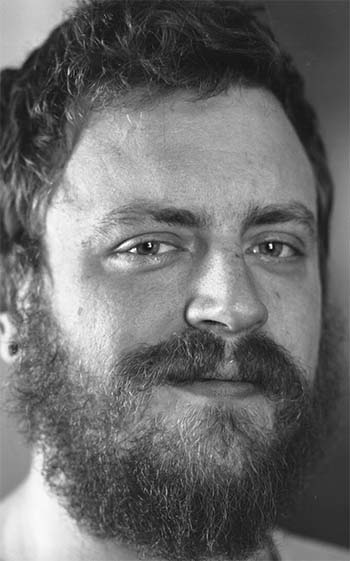

Shane McManus

Enter Shane and his father Keith McManus, local musicians and artists and proud citizens of Appalachia. In 2010, Keith purchased the Davis Theatre, a performance venue built in 1909. The Theatre had sat abandoned since the 1950s and fallen into disrepair. Shane has spearheaded the effort to restore the Theatre, preserving its historical façade and converting the interior into extensive artists’ studios. These include a woodshop, a bike repair shop, pottery kilns, music practice spaces, and more. These studios are now home to about 40 members of the Art Cooperative.

Shane puts their goals eloquently: “We are promoting the past, sustaining the future, and encouraging people to look around them and create with what they see.”

“Sustainability” is the big word for him. Not only does the Cooperative seek to give a reason for artists of all stripes to come to Greensboro, but it seeks to sustain the current population with cultural engagement and the earth itself with reuse-based philosophies. Ninty-eight percent of the materials that Cooperative artists use are recovered from trash, dug up from Greensboro’s rich veins of material history, or gifted to them by friends. Clay for the kilns is dug up from the same banks used by the Hamilton Company. Their bicycles are retrieved from local garages. Even the wood they use is pulled from decaying barns or burned-down buildings. Scrapping, dumpstering, recycling. They do their best to avoid spending money.

“In this part of Appalachia, I’ve always said the living’s easy. In the summertime, there’s always work to be found. In the wintertime, there’s always someone willing to share their harvest of whatever they had in their garden. The fat of the land is so rich, it’s kind of superlative to buy anything we need.”

Embracing Tradition; Building Community

That 200-year-old kiln has been restored and is firing new ceramics today. The artists in the Cooperative use many of the same art methods that Appalachians have always used, processing wood and clay just as their ancestors did long before they thought of it as “recycling” or “green.” Of their three pottery wheels, for instance, two are powered by the traditional method, spinning uniquely shaped pots every time. Shane hopes to one day use these wheels to launch a line of pots inspired by Greensboro’s 19th-century makers. It is this combination of the Davis Theatre’s space and Greensboro’s historical methods that draw members to the Cooperative.

And many have been drawn. The group claims members across 11 countries, ranging to France, Senegal, Ghana, and China. Many are musicians that are drawn to town to play a gig booked by Shane, often at the Antique Café. It is relatively easy to join. No portfolio or particular artistic expense is required. You simply have to earn the others’ trust. In exchange for access to the Cooperative’s resources, members must commit to a few hours a month volunteering to help repair the Theatre. This work is also great skill-building. Shane is a carpenter by trade and has taught one member, a musician from Maine who is nearly blind, how to swing a hammer and work on the building despite his failing vision.

The Cooperative’s resources include their studios, living space in town, and a huge array of scrapped supplies, such as large piles of local stained glass. But most valuable is their social network of committed craftspeople. Members regularly share skills and their own connections. This crosses borders, too. Greensboro has made friends with another art cooperative in Aarhus, Denmark, and the groups have now worked out an exchange program allowing members to visit each other’s spaces.

In the immediate, the Cooperative’s goal is to produce and sell quality works of arts by local artisans. In an economic sense, they one day strive to incorporate as both a small business and a nonprofit. They want to create a model where artisans cultivate their materials from the resources present in small towns like Greensboro and give back to those towns through public art and educational resources like their community garden. On a philosophical level, the Cooperative lives out the communal values of Appalachia and applies them to answer the problems that face the Mon Valley today.

Cooperative member Gabe Acita making a paddle.

Greensboro Pennsylvania Art Cooperative’s Core Values

Shane takes a view both practical and worldly. His investment is not just in the business or the artmaking, but in the ideas guiding both. When he talks about his aspirations for the Cooperative, he talks about notions of self, ideas borrowed from philosophies like Taoism and hippie back-to-the-earth movements. “It’s always been our goal [as humans] to distract ourselves from ourselves,” he explains, “so we should try to distract ourselves with something positive.” Hence art: an act where the mind can wander away from its worries and into a state of flow.

Though this suggestion seems simple, it is a complex part of how Shane works through the difficult history of the Mon Valley, where the same cycles of economic growth and decline have dominated for hundreds of years. “That’s the hardest part, is being able to read the future, to know when the next cycle is gonna hit. The best way I’ve found to do that is to listen—to not try to predict, but to know what is happening around me. So when I don’t feel like creating, I don’t create. When I don’t feel like participating, I don’t participate. Those are actions that I choose not to be counterproductive, but to be productive in a different way.”

Giving people the freedom to listen to themselves is one of the Cooperative’s core values. Its salvaged materials and low rental costs allow members to keep their expenses low, meaning that their need to sell work is lessened, allowing them time and space to create according to their own individual vision and internal clock.

Initiatives like the Cooperative abound in our region today, as many of us look to art and culture as a way to “revive” industrial areas we consider “dead,” but Shane is much humbler than that. “One of our mottos at the Cooperative is, ‘If you’re doing it, you can talk about it. If you’re not doing it, you cannot talk about it.’ We notice a lot of people saying to us, you could do this, you could do that, you could do this, you could do that. ‘You could make a lot of money doing that!’ And, yes, somebody could. But the question is, is it going to be you?”

“It’s mainly a focusing goal for us,” he continues, “because we’re so multidisciplinary. And the way we fill in each other’s gaps is by humility.” The Cooperative keeps their eyes on the immediate. Their approach to improving Greensboro is to ask, what can we do right now as the people we are? For them, it means not only creating a space for sharing work and knowledge, but also taking time along the way to honor their neighbors.

Cooperative member Keith Koury pouring ceramic cups.

Residents Coming Together, Defining Community

Not all that long ago, Greensboro almost ceased to exist. On Election Day 1985, Virginia and West Virginia were ravaged by floods as Hurricane Juan came to land and tore through them. The Mon Valley was hit hard, too. Large parts of Greensboro and other rivers towns were damaged by the rising river and ten inches of rain. Shortly thereafter, the Army Corps of Engineers began to redesign the Monongahela River dam system, threatening to raise the water levels permanently higher and destroy many of Greensboro’s oldest buildings.

Residents banded together to organize against this. Their efforts culminated in 1994 with the creation of the Nathanael Greene Historical Foundation, now called the Nathanael Greene Community Development Corporation. The NGCDC has launched many initiatives to preserve the town’s historic buildings and share them with the world. They now work with the Cooperative on a yearly cultural festival in Greensboro, Art Blast on the Mon. It is in this tradition that the Cooperative really arose – those people who refused to let Greensboro die.

Shane speaks about elders with the utmost respect. He admires people like Betty and John Longo, who owned and operated the local confectionary for decades, even as businesses elsewhere in town disappeared. And, when he reflects on the ways the Cooperative most improves Greensboro, what he calls “the giveback,” his mind does not immediately go to economic development or their community arts initiatives—it goes to them. “Emotionally and spiritually, we have gained so much from helping the seniors in town,” he says. “Their kids are no longer in town, grandkids no longer in town, and they need someone to just listen to them, really. And when I think about it, that’s probably the proudest thing I’ve done at the Cooperative, is talking to the seniors and hearing their stories. Some of them aren’t around anymore to tell them.”

“Really, they’re all artists in their own way.” He reflects on not only the glassblowers and the potters, but also the miners and ice cream shop owners. “They brought their artistry with them wherever they went!”

Guided by this respect, members of the Cooperative seek to help their neighbors naturally, in the course of their daily lives. “It’s that Buddhist notion of karma,” Shane says, “We all have to find something to give every day.”

For instance, one older woman in town walks from her home to the post office each morning as part of her daily exercise routine. When it snows, Shane and the others will shovel the sidewalk for her. On other days, the Cooperative will load up in their trucks and drive out to a local florist to collect discarded flowers from their dumpster. Some of these they keep for art, but most they hand out at local retirement homes. “It’s about becoming the heroes of that moment,” he concludes.

“It can be as simple as just picking flowers out of the garbage. And all the moments leading up to it, the driving, the traffic… everything leading up to donating that flower might be mundane. But that moment when you give that flower to that senior, I see the spark in their eyes. And first-time members who have never been on these trash-picking journeys before, they’ve never had that opportunity to be a hero in the moment. It’s a moment that, if we pay attention to and listen to, it can linger on inside of us. We can dwell on it for a really long time and it can create opportunity for creation. We don’t just feel good about ourselves because we’ve achieved something, we know we want to continue that feeling of good and continue that achievement.”

This is the real utility of the Cooperative—empathy. As Shane puts it, though he enjoys creating art, he is most motivated to do so when working with a community. This goes not only for art, but for improving the Theatre or simply being kind.

“When we work together as a group,” Shane says, “we find something that we can’t find alone. It’s a simple word—it’s called ‘muse.’ Like, as in to amuse, as a word. To amuse somebody is to give them the inspiration of humor, or of joy, or of just sorrow. Sorrow can be amusing. So that’s the benefit of a cooperative. You have somebody who’s pushing you, not to create necessarily, but just to have somebody there with you doing their thing is really powerful. It’s an opportunity to say ‘yes’ to another experience.”

Read more in the Heritage Highlights series. In this story, Jon Engel visited Tarentum, PA, host to Holy Martyrs Parish, a Catholic church with roots in the 19th-century industrial boom and the only church in America that carries on the tradition of creating sawdust carpets to mark religious events.