St. Peter & St. Paul Ukrainian Orthodox Church. Image courtesy of Chris Mills.

St. Peter & St. Paul’s Pysanky Sale

By Jon Engel

One of first things I noticed about Carnegie is the train tracks that divide it. Built during the peak of mill production, they run beside James Street between the diner and the ceramics supply store. Now, they are integrated by concrete overlays into the borough’s road map, part and parcel of the town. Before they were here, Alice O’Neil tells me, this side of Mansfield Boulevard was all housing, torn down when the highway expanded to two lanes. When she was a child, the working people of Carnegie lived there and walked to church.

To her family, that church was St. Peter & St. Paul Ukrainian Orthodox, which sits now between the Ukrainian-American Citizens’ Club and Holy Virgins Russian Orthodox. Like much of Carnegie at the moment, it is adorned in blue and yellow. The Ukrainian immigrants here came to the mills over a century ago, but have stayed rooted in this place, their culture continuing even as the circumstances around them have changed dramatically. I thought about this as I ate lunch at a local joint, Sunset Pizza, which sits on a historically brick road in the middle of Main Street. The employees chatted idly in Turkish as a Ukrainian flag flapped into my eyeline, pulled into view by the breeze. I finished my meal and made my way to St. Peter & St. Paul.

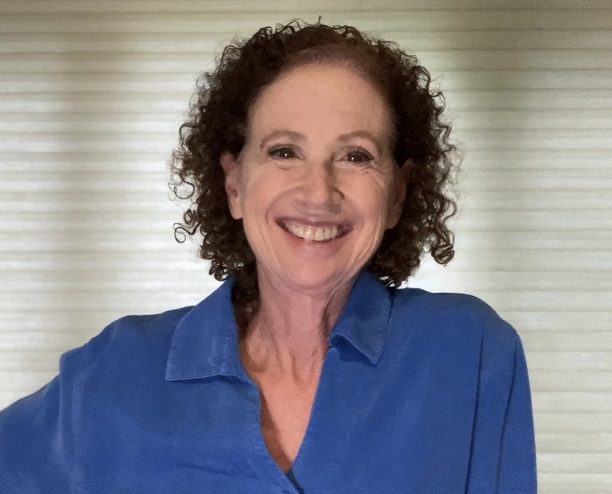

Cynthia Haluszczak shows an egg featuring the traditional net design—Christ is the fisher of men.

Faith and Family

I was first invited to St. Peter & St. Paul’s church by Michael Kapeluck, the lead organizer of the church’s annual pysanky sale. Each year, a friendly crew of church folk works to produce somewhere between 400 and 500 dyed eggs, which are lovingly decorated with intricate patterns steeped in traditional symbolism. These eggs are sold alongside traditional Ukrainian foods like stuffed cabbage and beet soup on Palm Sunday every year, as they have for decades, echoing the even older tradition of springtime pysanky.

The first pysanky eggs were created by ancient Ukrainians before the arrival of Christianity. Back then, they were sun worshippers who lived by the course of the agricultural seasons. They tended crops and kept animals, most importantly bees and chickens. The winter was a time for mending, housekeeping, reflection, and dreaming of the next year. The practice of pysanky grew from these short, cold days, where the house was lit by candles and hands were more idle. The women of this culture developed a practice of sketching on unused eggs with melted beeswax. They created complex works of metaphor, weaving the imagery of their everyday lives into prayers and fortunes. A sketch of a ram became a symbol of masculine strength, to be given as a blessing to the male head of the household. The pattern of a pine needle, the only plant to survive the snow, became a symbol of life used to conjure a bountiful harvest for the next year. Eggs were created both as charms and simply to beautify, left around living areas or hidden in the rafters of homes.

Christians began to evangelize Ukraine as early as the 800s, eventually leading to the development of many churches, including the Ukrainian Orthodox Church of which St. Peter & St. Paul is part. As the culture shifted to this new faith, pysanky persevered, becoming metaphorically tied to the arrival of spring and the resurrection of Jesus Christ. Old symbols shifted meaning and were joined by new ones, like crosses, Christian fish, and tears of the mourning Mary. Still, the process by which the eggs were created remained largely unchanged, even as Ukrainians began moving to the United States during the industrial boom of the late 1800s, when many of the families that now make up St. Peter & St. Paul’s congregation settled in Carnegie.

Many of those who attend the church now learned pysanky from their parents or grandparents, inheritors of family traditions as distinct as Ukraine’s many regions and towns are from one another. However, the annual sale can be traced back to two women. Michael’s mother, Beverly, was born in Minneapolis, Minnesota, where she attended St. Michael’s Ukrainian Orthodox Church. Through a series of national events between Orthodox churches, she met St. Peter & St. Paul’s Stephen Kapeluck, whom she married. She moved to Carnegie to live with him and brought St. Michael’s pysanky practice with her. At St. Peter & St. Paul, the priest’s wife, Tillie Beck, was already teaching the traditional art to some of the parish children. Together, Beverly and Tillie organized a series of demonstrations and sales to raise funds for the church. This eventually developed into the annual sale, which has run for more than fifty years, attracting customers and collectors from Pennsylvania, West Virginia, and Ohio.

Most of St. Peter & St. Paul’s current crop of egg-makers learned the craft from others in the church and primarily practice the art to support the annual sale. Across the decades, all have become extremely skilled and passionate, delicate with their tools and close to one another. They joke as they work, egging each other on, gently teasing. Carnegie is a small town, and St. Peter & St. Paul is a small church. Both literally and spiritually, the members are family, praying together for decades, attending events together, intermarrying, dancing the old dances, and making pysanky. Their humor and their affection affirm their work, and the work affirms their community. They are one and the same.

“I personally believe that church begins when you come out of the building,” says Sherri Walewski. “I believe in the community. During COVID, we couldn’t do certain events, so we just did ‘em outside . . . People were still so happy to come and socialize, come and get food. Same thing with the pysanky sale.”

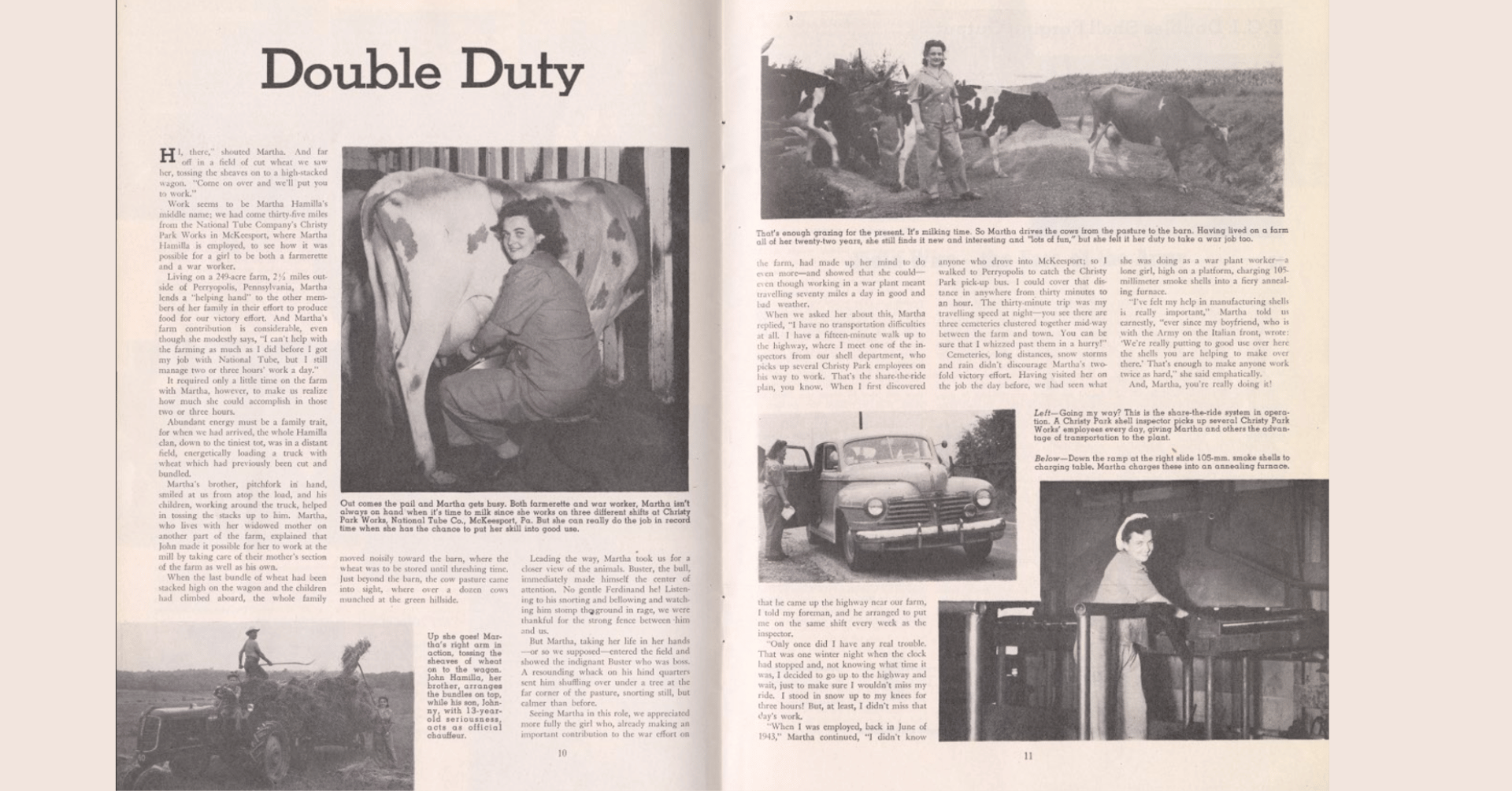

Sherri Walewski and Cynthia Haluszczak make pencil sketches on the eggs.

Making the Eggs

In Ukraine, and even at St. Peter & St. Paul, pysanky styles vary greatly. One of the biggest deviations is the Lemkos tradition, native to the Western Ukrainian region of the same name. As Alice describes to me, this is a tradition of the especially poor, who had no access to the dyes that other regions might have. Her mother’s family replicated this with melted crayons in America. “When they were growing up,” Alice explains, “they didn’t have a lot. They would put the crayons in a pot on the stove and then they would cover them with a lid to melt them. And she would have a straight pin with a little ball on the end. She would put that into a pencil, at the end of an eraser, and she would dip it into the wax and then make the stroke.” This produces white eggs with the design raised from the shell. Ukrainians and Ukrainian-Americans have used techniques like this to recreate traditional patterns for centuries.

The standard method practiced at St. Peter & St. Paul is similar. Designs are drawn in pencil by the individual artist, or by members Pat Sally and Cynthia Haluszczak. These drawings are used as the base for future lines, which are traced in melted beeswax, just as ancient Ukrainians used. The eggs are then dipped into dyes—traditionally brewed from vegetable material like onion skins and beets—now replaced with chemical colorants like those used for American Easter eggs. The wax solidifies so that when the egg is submerged, the dyes can’t reach the shell beneath and those lines stay white. Colors and shapes are layered over and over through the repetition of this technique, so that the final pattern builds in reverse, ending with the background color.

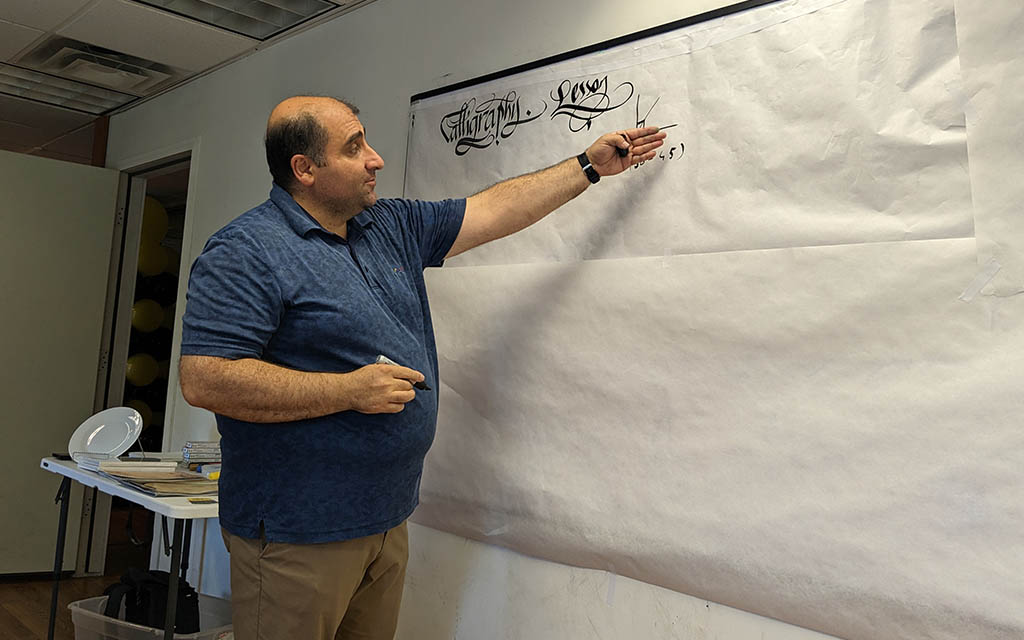

Tracey Sally chats with Jon Engel as she works.

The pysanky-makers draw their lines with a specialized stylus called a kitska, which consists of a small bowl with a dripping point. Traditionally, kitskas are heated over a candle flame so that they can scoop chunks of wax from the honeycomb and let them melt naturally. However, during my visit, artist Tracey Sally was using an electric kitska that heats itself. Tracey is, in many ways, a modernizer of the pysanky tradition. She married into St. Peter & St. Paul through her husband, Mike Sally, son of Pat, and learned the practice from them. Now she applies contemporary techniques like tie dyes to her eggs and pulls design inspirations from tissue boxes and floral purse interiors. “There are people who will sit down and just plan out their whole egg,” she explains. “I don’t. I have a rough idea of what I want, and then I just go from there. I pull a lot from the tradition too—even a lot of my contemporary designs have some inspiration from the traditions. I’m not Ukrainian, [but] I love Ukrainian culture. Ukrainians are a very unique people. They have a lot of background, and most Ukrainians will carry that with them.”

Mike and Tracey, like the church as a whole, bond over pysanky. “The one time, how many years ago was it?” Mike recalls, “We decided to take a vacation together, and we went up to our family’s camp up near Tionesta. There’s no TV, nothing to do. You can put on the radio, that’s it. We had a potbelly stove to keep us warm, and we sat and we made about five . . . five and a half dozen pysanky in one weekend. We just kept cranking ‘em out. You get tired, go to sleep. You get hungry, make something to eat. Just the middle of the woods, sitting around.”

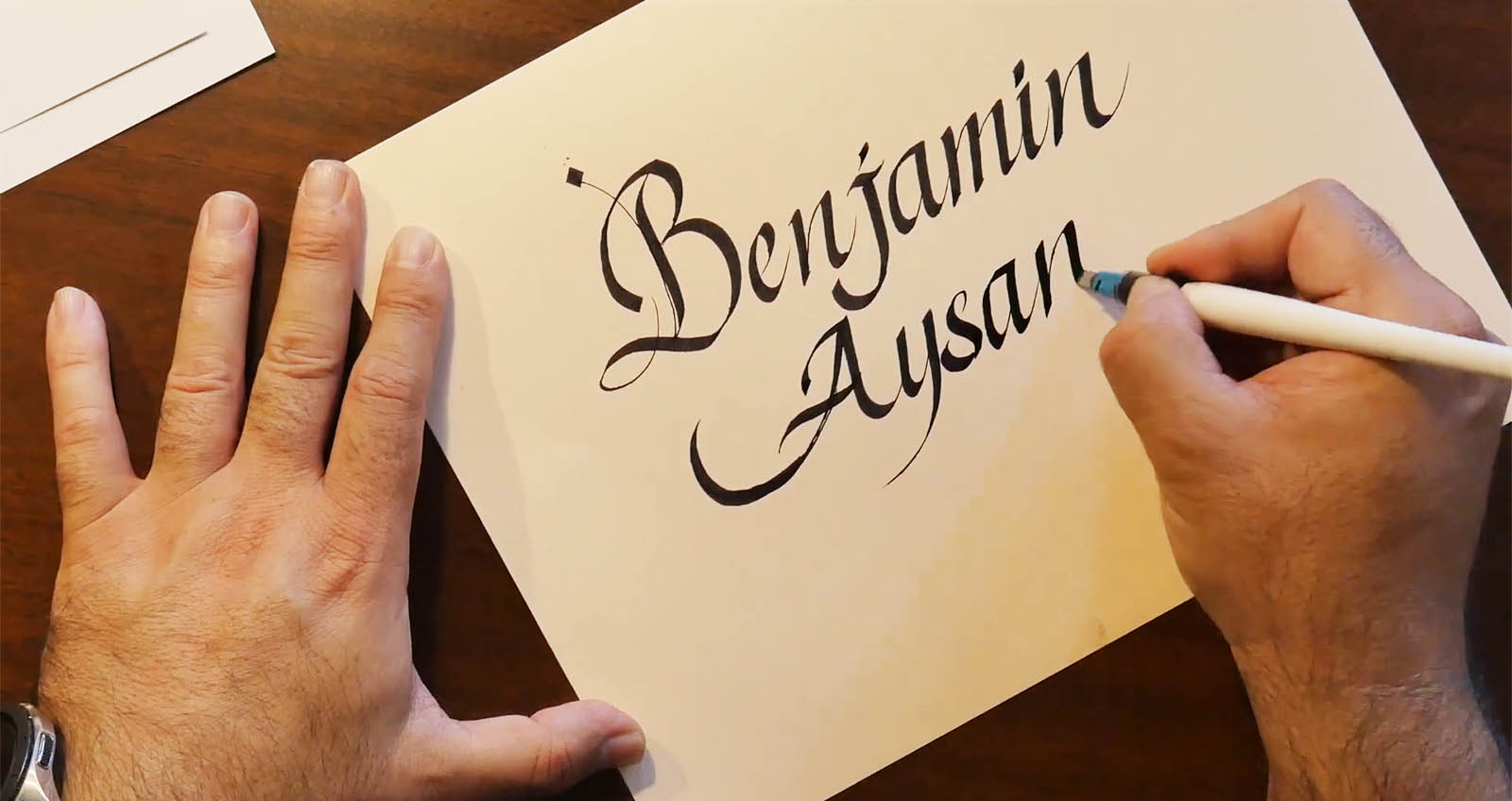

Michael Kapeluck strips an egg by melting the wax.

When all the color layers are dyed in, the wax lines are “stripped” from the egg, revealing the full, multicolored patterns beneath. This is done by holding the egg over a candle flame so that the wax melts again and can be wiped clean from the shell. Michael Kapeluck and his wife Michele were stripping cartons of freshly made eggs when I sat beside them to chat.

Michael has inherited his mother’s position as point person for the pysanky activities, just as there is someone responsible for organizing the food sale and the monthly clothing donations. Michael has been an artist since he was a child and is a graduate of the studio arts program at Carnegie Mellon. As he tells it, he spent a few years as a modern artist, showing works in local galleries. But he began to find the work hollow. “I just got bored of the art world,” he says. “I think it’s the connection—the kind of internal connection. You’re always trying to reinvent yourself. I feel like the contemporary art world just became about the individual artist—it ceased to have any real roots. It just didn’t have that world connection.”

Some time ago, he began to focus his energies on traditional religious art entirely. Other than the pysanky sale, he works as a professional iconographer, painting various pieces for Eastern Christian churches around the country in continuation of Orthodox aesthetic traditions. “The art form itself is what art used to be before the modern era,” he explains. “There was no difference between art and science. The Renaissance and the Enlightenment and all that started separating all these things into different categories. Science, magic—it all just merges. And that’s what iconography is. It isn’t just a pretty thing to hang on the wall. It serves a function.” That much is surely true of pysanky too, steeped in wishes for good fortune.

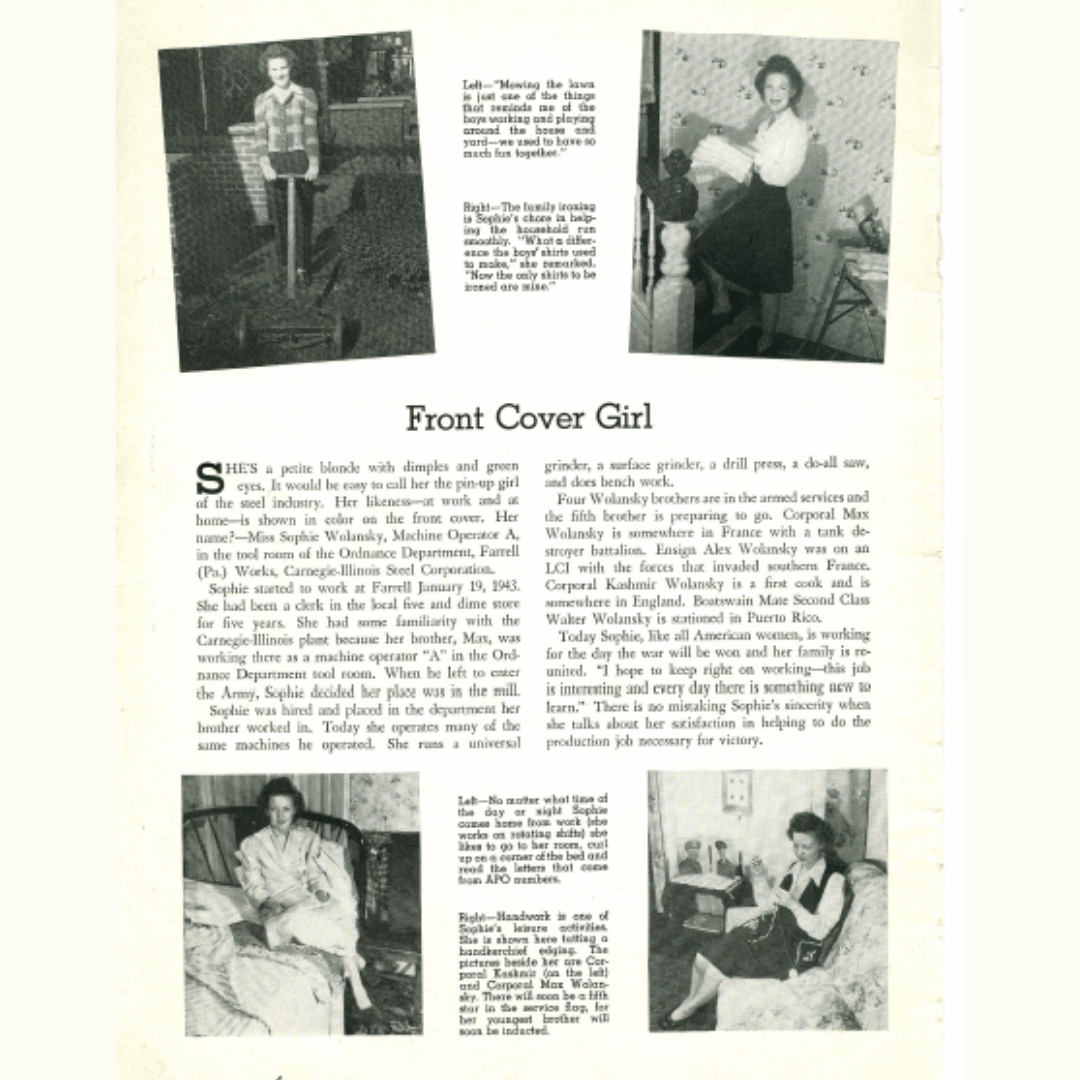

A dyed egg in the colors of the Ukrainian flag, halfway through being stripped of its wax.

Michael sighs as he reaches for the next egg from the crate. “Who did a yellow egg?” he says with a touch of dry irony. “Who did a yellow egg?”

“Is there a problem with a yellow egg?” I ask.

“It’s hard to take the wax off,” Michael explains. “It scorches because it’s lighter. You get the carbon from the flame on it. It’s a pain in the rear end.”

“That’s why it’s usually best to have a darker color as the last color,” Michele adds.

But of course, this egg was yellow and blue to evoke the Ukrainian flag. I asked: did they know why these colors were chosen to represent the nation? Michael nodded. Blue for the clear skies, yellow for the bountiful grain. The flag stands for the horizons of pastoral Ukraine, the breadbasket of Europe.

“The wheat fields,” Michele says wistfully, her eyes fixed on the egg in her hands, “that are all getting destroyed.”

Volunteers in the middle of loading the trucks of donations to Ukraine.

A Long-Held Tradition

Throughout, our conversation was often disrupted by a storm of footsteps thundering out over our heads. Initially, I assumed that the dance group was practicing above us, but I came to learn that their practice space had been filled with boxes—diapers, canned foods, clothes, and medical supplies. St. Peter & St. Paul had collected two moving trucks full of critical needs to aid Ukrainians during the invasion, which were moved by a volunteer team of nonparishioners in the course of an afternoon.

Like the donations drive, the pysanky sale is the work of ordinary people who are extremely dedicated. Tracey is the manager of Carnegie’s Rite-Aid. Alice works at the local Lowe’s. Carnegie is a town of around 8,000 people. St. Peter & St. Paul has around 100 members. Within this community and this art form, each of them has a significant influence over the world—they are the creators of distinct and refined works, their signature choices of color and linework recognizable to each other and their patrons, their capacity for creativity and organization limitless.

Above all else, pysanky eggs represent the changing of the seasons. Nearly all of the traditional symbols—the ancient symbols and the pagan forms—are omens of spring. Birds flock back from their winter migrations. Flowers bloom to collect the morning light. And the sun is everywhere—once a representative of the Ukrainian sun god, now the Christian son of God—either way, warmth, surging back toward the springtime.

The eggs themselves are perhaps the most potent symbol. Each of them contains a literal piece of life (or contained, as some have their yolks blown out through a pinhole poked at the top of the shell so as not to rot). They are ephemeral and delicate and full of potential. They are symbols of birth and rebirth, adorned with many colorful lines that trace their circular bodies. Functionally, these are used to divide the image into sections, but they are also by far the most recurring visual element for deeply spiritual reasons.

“They represent eternity,” Michael notes. “Lines that go on without beginning or end.”

Following that line, we see what the Ukrainians have always known across eons, religions, and nations—inevitably, all things change. All things die. And all things live again.

And still, across it all, the children of the farmlands sit with their needles, drawing lines along their eggs, just as it has been for centuries.

St. Peter & St. Paul Ukrainian Orthodox Church’s annual pysanky sale will take place at their church, 220 Mansfield Boulevard, on Sunday, April 10, from 11:00 a.m. to 4:00 p.m. You can also read more about Michael’s iconography work at archangelicons.com.

Jon Engel is the Heritage Arts Coordinator for Rivers of Steel and the author of the Heritage Highlights column.

Jon Engel is the Heritage Arts Coordinator for Rivers of Steel and the author of the Heritage Highlights column.

By Jonathan Engel

By Jonathan Engel