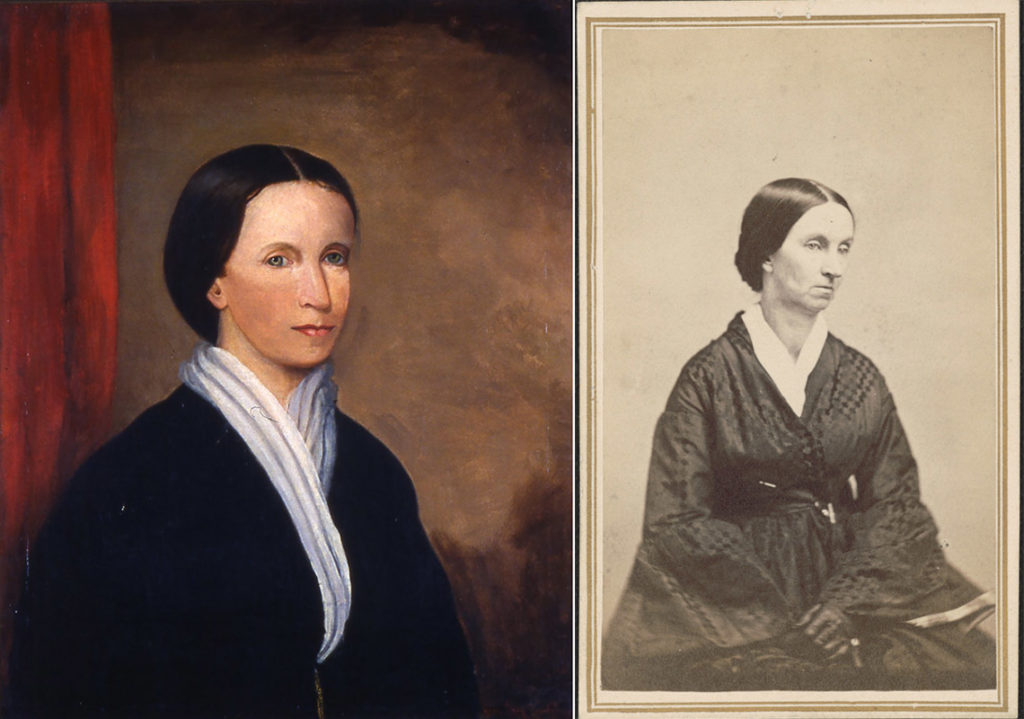

A detail Jane Grey Swisshelm’s Self-Portrait, circa 1840-1845 / Senator John Heinz History Center, Courtesy of N.N. Moore.

Woman’s History Month Feature: Jane Grey Cannon Swisshelm

To celebrate Women’s History Month, Rivers of Steel’s Interpretive Specialist, Dr. Kirsten Paine, crafted two articles on one of her favorite topics—Jane Grey Cannon Swisshelm. In part one of this twofer, Kirsten examined the life of this woman who was clearly ahead of her time. Using Swisshelm’s autobiography as a starting point, Kirsten leaned on her own expertise in literature from that era to provide context for understanding this pioneering woman. In today’s piece, she digs in further, focusing on Swisshelm’s career as a reporter, newspaper publisher, women’s rights advocate, and abolitionist throughout the nineteenth century.

To celebrate Women’s History Month, Rivers of Steel’s Interpretive Specialist, Dr. Kirsten Paine, crafted two articles on one of her favorite topics—Jane Grey Cannon Swisshelm. In part one of this twofer, Kirsten examined the life of this woman who was clearly ahead of her time. Using Swisshelm’s autobiography as a starting point, Kirsten leaned on her own expertise in literature from that era to provide context for understanding this pioneering woman. In today’s piece, she digs in further, focusing on Swisshelm’s career as a reporter, newspaper publisher, women’s rights advocate, and abolitionist throughout the nineteenth century.

By Dr. Kirsten L. Paine

A Keen Sense of Self-Awareness

In a letter dated August 7, 1882, Jane Swisshelm declines her daughter’s invitation to stay. She writes to Nettie, “We see and estimate things so differently that it is quite out of the question for me to avoid being a source of apprehension to you all the time we are together. You never know when I am going to hurt someone’s feelings or do something to make myself ridiculous.” These lines highlight tension in their relationship, but they also demonstrate Swisshelm’s self-awareness. She is not always polite, and she can make people uncomfortable. Besides, she has work to do in Pittsburgh, she continues. The city “is in debt twice the amount the state Constitution allows. Her water works are a failure. I have exposed the fraud until the councils have sent an agent to talk or wheedle me into silence.”

By 1882, Jane Swisshelm had returned to Pittsburgh for good. Her work in journalism, nursing, and political activism had taken her to St. Cloud, Minnesota, Washington, D.C., Chicago, Illinois, and towns in between. However, Pittsburgh had changed in the intervening years, and she felt the strain of its expansion as industrial production boomed in the Monongahela River Valley. In Swissvale, the Allegheny Car and Transportation Company made state of the art rail freight cars. In Braddock, the Edgar Thompson Works was the first of Andrew Carnegie’s new integrated mills. Across the river in Homestead, Carnegie opened Homestead Steel. As Sylvia Hoffert notes in her biography, Jane Grey Swisshelm: An Unconventional Life, 1815–1884, “the world was closing in on her” (Hoffert 184). Still, Swisshelm had work to do.

At the time, she had intended to take up a new series “for lecturing in the Opera House or Library Hall every Sunday afternoon by way of teaching people how to live” (Swisshelm, 1882). She insists, “there is no one but me for this work” (1882). She closes this letter to her daughter by asking that her husband, Ernest [Allen], write to her again about “building workmen’s houses here” as thousands of laborers poured into the Mon Valley seeking work in the new factories.

Two portraits, about twenty years apart. Left: Self-Portrait, Jane Grey Swisshelm, 1840-1845 / Senator John Heinz History Center, Courtesy of N.N. Moore. Right: Jane Grey Cannon Swisshelm, journalist, activist, and Civil War nurse, Joel E. Whitney, photographer / Whitney’s Gallery, St. Paul. United States, ca. 1865. Courtesy of the Library of Congress.

An Astonishing Career Begins with Letters to the Editor

For decades, Swisshelm believed “there is no one but me for this work,” and built an astonishing career in the United States as a preeminent journalist and reporter on behalf of many progressive causes. Her journalism career began in Pittsburgh in the late 1840s when she wrote a series of letters to the editor of the Pittsburgh Commercial Journal, Robert M. Riddle. These letters take up one of the tenets of the early women’s rights movement: the right for women to own property. Riddle published several of these letters. On October 28, 1847, Swisshelm writes about how a husband assumed all legal authority over any of his wife’s assets: “All they both have and all they can acquire are his, and only his, to dispense as he sees fit.” On December 11, 1847, Swisshelm writes, “There are that matter of quirks, wibbles and turns in the laws which relate to married women, and there is not one lawyer out of fifty who understands them or is fit to conduct any business which concerns them.” These letters to the editor seem like radical public statements; however, Swisshelm builds on an existing foundation of women writers who circulated their own ideas in print.

Throughout the early decades of the nineteenth century, middle-class white women like Swisshelm found limited opportunities to express political opinions in public. Popular fiction, especially novels and short stories, represented one opportunity for women writers to discuss their ideas with a reading audience. For example, Lydia Maria Child, known primarily today for editing Harriet Jacobs’s memoir, Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl (1861), wrote the acclaimed novel Hobomok, a Tale of Early Times in 1824. Catherine Maria Sedgwick, a best-selling writer from Massachusetts, published short stories in periodicals from the 1820s through the 1850s. Her most famous novel, a historical romance, titled Hope Leslie, was published in 1827. Both of these writers use historical fiction to explore questions about women’s and Indigenous people’s rights. Since women also comprised most of the reading audience for books like these, women novelists cultivated ecosystems for the public exchange of social, cultural, and political ideas that eventually developed sophisticated organizational and communication networks between women.

By the time Jane Swisshelm penned her first political opinion pieces as letters to the editor in the Pittsburgh Commercial Journal, she actively participated in a thriving culture of women writers. Her important steps forward came at a moment when other women like her began organizing en masse to demand rights to property, inheritance, divorce, and custody of children, as well as the vote. Publisher Robert Riddle owned other newspapers in Pittsburgh. In addition to the Pittsburgh Commercial Journal, he owned the Daily Gazette, Daily Morning Post, Mystery, Albatross, Spirit of the Age, and Pittsburgh Catholic. Newspaper publishing in the 1800s was a lucrative, if risky, investment. Some newspapers established broad subscription bases, while others occupied niche areas of interest. Countless newspapers went bankrupt after brief runs while other newspapers ran for decades. As emerging industrial technology made it feasible to make periodicals relatively cheap to produce and inexpensive to purchase, more newspapers meant more opportunities for marginalized voices to find reading audiences. That was the prevailing idea for Jane Swisshelm. She saw an opportunity to create change, and she took it. Because Swisshelm contributed to several Pittsburgh papers and gained a loyal—oftentimes vocal—readership, she approached Riddle with an idea. What if she edited and published a newspaper of her own?

The Pittsburgh Saturday Visiter—Swisshelm’s First Newspaper

Mrs. Jane Grey Cannon Swisshelm, image courtesy of the Minnesota Historical Society. Scan from original on Epson Expression 10000XL. Full credit below.

By Swisshelm’s own account, Riddle initially was unsupportive. She writes about his response in her autobiography, Half a Century: “I was going to start the Pittsburgh Saturday Visiter; the first copy must be issued Saturday week, so that abolitionists would not have time to be discouraged, and that I wanted him to print my paper” (Swisshelm 106). The city’s abolitionist outlet, Albatross, went bankrupt, and its demise created a vacuum for progressive political writing. According to Swisshelm, Riddle did not immediately take to her idea. She writes, “he had pushed his chair back from his desk, and sat regarding me in utter amazement while I stated the case, then said: ‘What do you mean? Are you insane? What does your husband say?” (106). Eventually, Swisshelm convinced him her husband’s opinion did not matter. He agreed to this venture together, even if he refused to furnish her with her own desk (108).

The Pittsburgh Saturday Visiter was Swisshelm’s first newspaper. It was also the first Pittsburgh-based newspaper with a woman at the helm. Swisshelm celebrated this achievement: A woman had started a political paper! A woman! Could he believe his eyes? A woman!” (113). The inaugural edition of the Visiter was published on December 20, 1847. From the outset, Swisshelm intended the paper to highlight, advocate for, and provide a platform to abolitionist and women’s rights writing, and by the end of 1848, the Visiter had over 6,000 subscribers. Throughout the newspaper’s run from 1847 to 1854, Swisshelm maintained a strong, if sometimes controversial, editorial hand and a clear political voice.

For example, in 1849, the Visiter received pushback in the form of an opinion piece from a competing Ohio newspaper called the New Concord Free Press. In it, the writer claimed that the Constitution itself guarantees the continuance of slavery and attacked Swisshelm’s position; in true editorial fashion, Swisshelm responded to this argument with her own. Her characteristically witty tone and sharp dissection of language shines through a response published in the Visiter’s February 17, 1849 edition. She writes, “Who are ‘the people’ of a country? Webster says it is ‘each, every one, common people. The body of persons who compose a community, town, city or nation.’” She continues to argue, “these people of the U.S. ordained the Constitution to secure the blessings of liberty to themselves and posterity. All slaves were a part of the people, and lest there should be a mistake, they are named as ‘persons held to labour.’” In the conclusion to her article, as the Constitution cannot support simultaneous liberty and slavery, and if the Constitution does guarantee slavery, the document “is not worth straw enough to burn it.”

A Progressive Power

After the Seneca Falls Convention in 1848, women’s rights issues, not just the right to vote, gained national traction. Some argued that the abolition of slavery should happen as part of a broader push for equal rights for women. The Visiter took up many of these arguments, and Swisshelm frequently published her own opinion columns. In her 2006 dissertation, “Women of reform: The periodical editing careers of Margaret Fuller, Lydia Maria Child, Caroline Healey Dall, and Jane Grey Swisshelm,” Terri Amlong investigates the ways in which several of Swisshelm’s articles combine her political stances with personal experiences. Her acrimonious divorce from James Swisshelm was not finalized until 1857, and it was granted only after protracted court battles over property and custody of their daughter, Mary Henrietta [also known as Nettie or Zo]. Amlong highlights two important pieces. One, published in the August 18, 1849 edition, is a review of E.D.E.N. Southworth’s popular novel, The Deserted Wife: “[W]henever two are really weary of each other, they are no longer married; and nobody can marry them—no combination of men can marry them. It is a base prostitution of the name and object of marriage, to bind two to live together contrary to the will of either.” Swisshelm asserts, [T]he State cannot be benefited by what is crime in the individual! The second appeared in the August 3, 1850 edition. In this piece, Swisshelm argues that expecting women to “marry either for a living or to maintain a respectable standing in society” is a disservice to all women. Instead of training girls only to become wives, Swisshelm maintains “all be educated in some useful employment or profession, whereby they may get as good a living as a man can get.”

Journalism was “as good a living as a man can get” for Jane Swisshelm. She sold The Pittsburgh Saturday Visiter to her co-editor and friend Robert Riddle in 1854, and publication of the paper shuttered shortly thereafter. Swisshelm moved to St. Cloud, Minnesota, where she started two more newspapers: the St. Cloud Visiter and the St. Cloud Democrat. She continued to write for the rest of her life. She made friends with the likes of Lucretia Mott, Susan B. Anthony, and Elizabeth Cady Stanton, and she made political enemies on both sides of the Mason-Dixon Line. Whether in Minnesota, Washington, D.C., or on Civil War battlefields, Swisshelm’s commitment to the written word—to the power of the press and women’s power won by the pen—prevailed. The Pittsburgh Saturday Visiter remains her most influential contribution to American journalism and her lasting legacy in the venerated Pittsburgh newspaper industry.

Bibliography

Amlong, Terri A. “Women of Reform: The Periodical Editing Careers of Margaret Fuller, Lydia Maria Child, Caroline Healey Dall, and Jane Grey Swisshelm.” Order No. 3232483 University of South Carolina, 2006.

Hoffert, Sylvia D. Jane Grey Swisshelm: An Unconventional Life. Chapel Hill, N.C.: University of North Carolina Press, 2004.

Pittsburgh Saturday Visiter. (1847–1854) (microfilm)

Swisshelm, Jane. Half a Century. Jansen, McClurg & Company, 1880.

Swisshelm, Jane Grey, “Letter, Jane Grey Swisshelm to Nettie Swisshelm [August 7, 1882]”

(1882). Jane Grey Swisshelm Letters. 18. https://repository.stcloudstate.edu/jswiss-letters/18

Image Credits

In order of appearance:

Swisshelm, Jane Grey, painter. Self-Portrait. Ca. 1840 – 1845, painting. / Senator John Heinz History Center, courtesy of N.N. Moore.

Whitney, Joel E, photographer. Jane Grey Cannon Swisshelm, journalist, activist, and Civil War nurse / Whitney’s Gallery, St. Paul. United States, ca. 1865. [St. Paul, Minnesota: Whitney’s Gallery] Photograph. Courtesy of the Library of Congress.

Whitney, Joel E, photographer. Mrs. Jane Grey Cannon Swisshelm / Whitney’s Gallery, St. Paul. United States, ca. 1860. [St. Paul, Minnesota: Whitney’s Gallery] Photograph. Courtesy of the Minnesota Historical Society.

Enjoy Dr. Kirsten L. Paine’s article? Read another story from the A Literary Look series.