A detail of Jan Loney’s Flight sculpture from Alloy Pittsburgh 2021 in front of the stack and stoves of the Carrie Blast Furnaces.

Life in the Iron Mills and the Industrial Muse

A Literary Look is a new series that features recommended reads from the Rivers of Steel staff. For the inaugural post, Dr. Kirsten L. Paine, our site management coordinator and interpretive specialist, offers up an examination of one of her favorite books, Life in the Iron Mills, a novella by Rebecca Harding Davis that was first published in The Atlantic Monthly in April, 1861. In this piece, Kirsten examines the enduring legacy of the industrial muse and how the human spirit can triumph over the laborer’s toil.

A Literary Look is a new series that features recommended reads from the Rivers of Steel staff. For the inaugural post, Dr. Kirsten L. Paine, our site management coordinator and interpretive specialist, offers up an examination of one of her favorite books, Life in the Iron Mills, a novella by Rebecca Harding Davis that was first published in The Atlantic Monthly in April, 1861. In this piece, Kirsten examines the enduring legacy of the industrial muse and how the human spirit can triumph over the laborer’s toil.

By Dr. Kirsten L. Paine

“It always has seemed to me that each human being, before going out into the silence, should leave behind him, not the story of his own life, but of the time in which he lived.” – Rebecca Harding Davis, Bits of Gossip (1904).

When Rivers of Steel’s Alloy Pittsburgh 2021 tri-annual exhibition opened at Carrie Blast Furnaces in August 2021, visitors explored connections between multimodal art installations and their surroundings. The contrasts between Carrie’s sharpness and softness, light and shadow, riots of color and muted tones altogether enhanced, engulfed, challenged, played with, echoed, and reflected six pieces of art from six distinct perspectives. Visitors to the site found themselves immersed in an environment that can transform all manner of human experience. The furnaces are giants that made the twentieth-century out of fire. They stand in witness to thousands of stories about that century and about the people who experienced it.

Sculptures of metal, glass, and rope; drawings and paintings of people and things; an enormous green jacket and invisible signs in the sky—all of these contain thousands of stories, too—stories about the people who lived and worked at the mill. The art, the work of making it, and the experience of seeing it, thrives in reciprocal community because it becomes a way for people to tell stories to themselves and to ponder a very big question: What does it mean to be human?

Bradford Mumpower’s installation at the Carrie Blast Furnaces was inspired by the “greens” that workers wore while on the job, scaled to a size proportionate with the historic importance of the site itself.

This universal question has innumerable answers, but here is one: being human means creating art. Life in the Iron Mills, a novella by Rebecca Harding Davis and first published in The Atlantic Monthly in April of 1861, is about a poor Welsh immigrant named Hugh Wolfe. Hugh is a puddler in an iron mill, and he spends his life turning ore into pig iron. As he works, Hugh skims the slag from the top of the molten iron and uses it to create strange and wonderful sculptures. He is a gifted artist, sensitive and delicate, but he is hardened by strenuous work. He lives with his cousin, Deborah Wolfe, a disabled woman who yearns for a more peaceful life. One day the mill’s owners and managers tour the facility and watch the workers, but they do not seem to recognize people like Hugh and Deborah as more than parts of their giant machines. The men leave, but through an increasingly desperate situation involving stolen money, confessions, and imprisonment, the Wolfes are left heartbroken. When the story ends, readers are left only with the sublime statue known as the Korl Woman and the narrator’s voice imploring readers to not just look at the conditions of working-class life, but to see people as inherently beautiful.

This is a basic plot summary of Life in the Iron Mills, and it sounds like a depressing book; however, the story is an opportunity for readers to discover light in the darkness. It remains one of the finest early examples of American realism, and it was a smash hit from the start.

In the 1860s, literary realism was one element of an emerging artistic style that sought to represent, through image and language, an authentic depiction of life. Photography demonstrated technological advancements in creating mirrored images of the day-to-day. In one frame, a photograph captured and held a moment in its most quotidian fashion. A photograph showed the human body with all of its imperfections, and such an image could represent a lifetime’s worth of memories.

Literary realism uses words in a way that closely follow what photography transforms with images. For example, Davis uses unvarnished language in her descriptions of a mill town, a furnace, the workers, and the struggle to hang on to one’s own life as “pits of flame waving in the wind; liquid metal-flames writhing in tortuous streams through the sand; wide cauldrons filled with boiling fire” (Davis 45).

Although it is a more contemporary image, this photo of the teeming process captures the color and heat Davis describes. Image from the collection of Rivers of Steel.

As you read, feel the heat as Deb, body hunched over from years of hard physical labor, brings a pail of dinner to her cousin the puddler. See the licks of orange and yellow fire as she walks past men with shovels and pickaxes. Imagine as the acrid sand tinges the nose. Deb walks past “crowds of half-clad men, looking like revengeful ghosts in the red light, hurried, throwing masses of glittering fire” and mutters—with a heavy Welsh accent—“’T looks like t’ Devil’s place!”(45). The straightforward language Davis uses compares the factory floor to Hell without going directly to that mythical place. It has what is called “verisimilitude,” or the quality of seeming real.

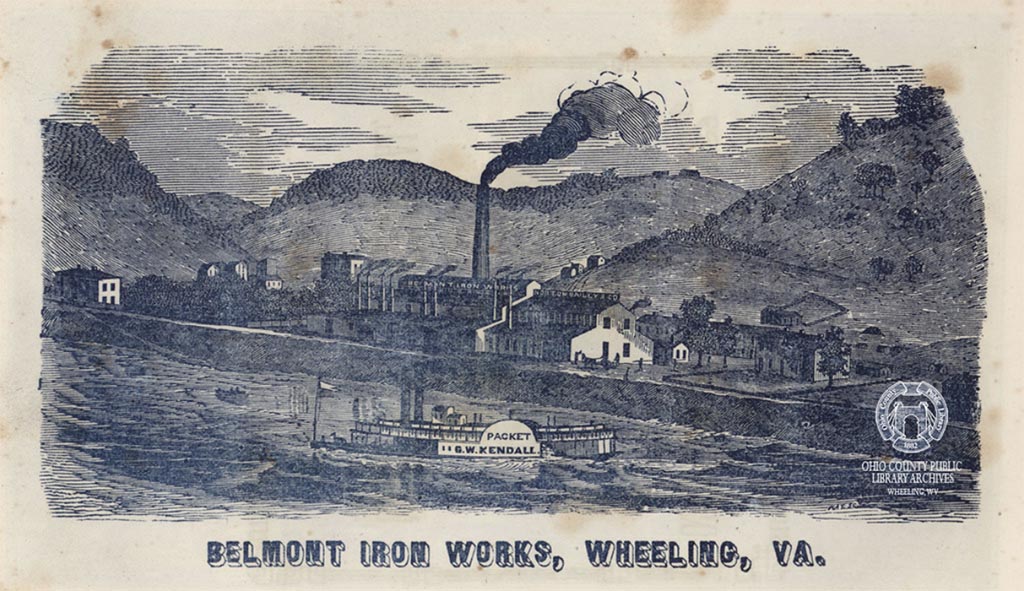

The Belmon Iron Works in Wheeling, West Virginia was likely the basis for the mill in Davis’ story. Image courtesy of Ohio County Public Library, Wheeling, WV.

Davis threads lifelike passages of exposition that capture the sights and sounds of a nineteenth-century iron mill between characters’ thoughts and conversations. When Mr. Clarke (the factory manager), Young Kirby (the owner’s son), Dr. May (the town physician), and Mitchell (the owner’s son-in-law) walk through the factory floor with a reporter to inspect the machines and marvel at the industrial wonders they have financed, they cannot grasp how or why one of their workers has made sculptures from korl. Korl, which is an older term for slag, is the limestone waste leftover in the smelting process, and it has been transformed. Hugh uses the off moments during his shift to chisel the “light, proud substance, of a delicate, waxen, flesh-colored tinge” into “figures,—hideous, fantastic enough, but sometimes strangely beautiful” (48). The men stop and stare at one piece in particular. It is a figure of a woman. She is twisted, knotted like tree bark, but she reaches upward with an outstretched hand and looks up. Her stone face wants for something. Mr. Clarke, Kirby, and the other professional, educated, middle class men—the men who do not actually make iron—discuss who she might be and what she might want, and then they ask Hugh. He answers them plainly, “She be hungry” (53). For what, they ask, not understanding what hunger is. He answers again, “summat to make her live, I think,—like you” (54). The group of men cannot seem to reconcile the juxtaposition of art and labor, so they nod and move on.

The rest of the novella plays on a continuing notion of hunger in the search for life’s meaning. Despair is found where despair is felt. Peace is found where peace is required. However, at the molten core of it, Life in the Iron Mills is about what happens to art when the machinations of industry wreak havoc on the human spirit. And yet it holds up a woman made out of slag, reaching, searching, as the salvo. The waste is not wasted. At the end of the story, the narrator brings the reader back to her room overlooking the Ohio River and reveals the korl woman hidden behind a window curtain. The dim morning “suddenly touches its head like a blessing, and its groping arm points through the broken cloud to the far East,” where the sun rises (74).

“Carrie Furnace Scenic View” appears courtesy of the William J. Gaughan Collection, University of Pittsburgh, July 1946.

In 2022, Life in the Iron Mills is mostly taught in college English courses. Sometimes readers stumble across the book by way of internet listicles, and sometimes readers discover it while combing through library stacks in search of something completely new. No matter the mode of introduction, Life in the Iron Mills is worth the time and attention paid to it because it tells the story of a time not so long ago and a place not so far away from Pittsburgh and a people not so different from who people are now. Try reading the book, and then come to visit Carrie this spring. See all the colorful graffiti, the welded chairs, and the deer made of hose, pipe, and wire. Walk on pathways laid in korl and consider all manner of art made on the site. Look at what human beings can make.

Bibliography

Davis, Rebecca Harding. Bits of Gossip. New York: Houghton, Mifflin and Company, 1904.

Davis, Rebecca Harding. Life in the Iron Mills. Boston: Bedford St. Martin’s, 1998.

Enjoy Dr. Kirsten L. Paine’s article? Read her piece Getting to the Heart of the Hardest Working River.