Collegiate women from the 1880s—Pennsylvania Female College, Class of 1888, Chatham University Chronological Photograph Files, Historic Pittsburgh Archives.

The Education of a 19th-Century Factory Owner’s Daughter

This story is the second in a series of articles about Carrie Clark Arkell, the woman who was the namesake of the Carrie Blast Furnaces. In this piece, Dr. Kirsten Paine examines the education of the young Miss Clark and gives context to what may have been expected from her, both from her family and from society.

By Dr. Kirsten L. Paine

Expanding the World of Carrie Clark

In my previous article that reintroduced Carrie Clark—the namesake of the Carrie Furnaces—to Pittsburgh, I compiled newly discovered information about a young woman’s life. Most of this information comes from newspaper articles and census reports, but the tidbits were enough to write a story about a woman born in the middle of the Civil War, who moved with her family to Pittsburgh at the beginning of the big steel boom, received an expensive education at an elite college, aided her father in expanding the family business, married a dashing state senator’s son, had a child, and died unexpectedly at twenty-five. This is a lot of life packed into two and a half decades.

Understandably, people had questions about Carrie Clark. What do we know about her family life? Why did her parents send her away to school? Was her marriage socially advantageous? Do we know what role she played in Pittsburgh’s industrial ownership circles? Why did she die so young? I want to try to answer some of these questions by putting some context around Carrie Clark’s life, even as we are still researching important details in her biography.

The latter half of the nineteenth century was a time of drastic social, cultural, and political changes. The Civil War (1861–1865) redefined every single aspect of American life. The transcontinental railroad (1869) connected east and west coasts, streamlining transportation and communication. The National Parks project (1872) began to set aside pieces of the American landscape to be held in public ownership. The women’s suffrage movement picked up steam even as it sought to expand beyond the issue of suffrage itself. The United States’ wealthy industrialists and venture capitalists of the Gilded Age curated Americans’ tastes in music, theater, and art.

In short, Carrie Clark’s life is both singular in the enduring legacy of her name—Carrie Furnaces—and typically representative of the kind of life led by a woman in a white, upwardly mobile middle class family of the time.

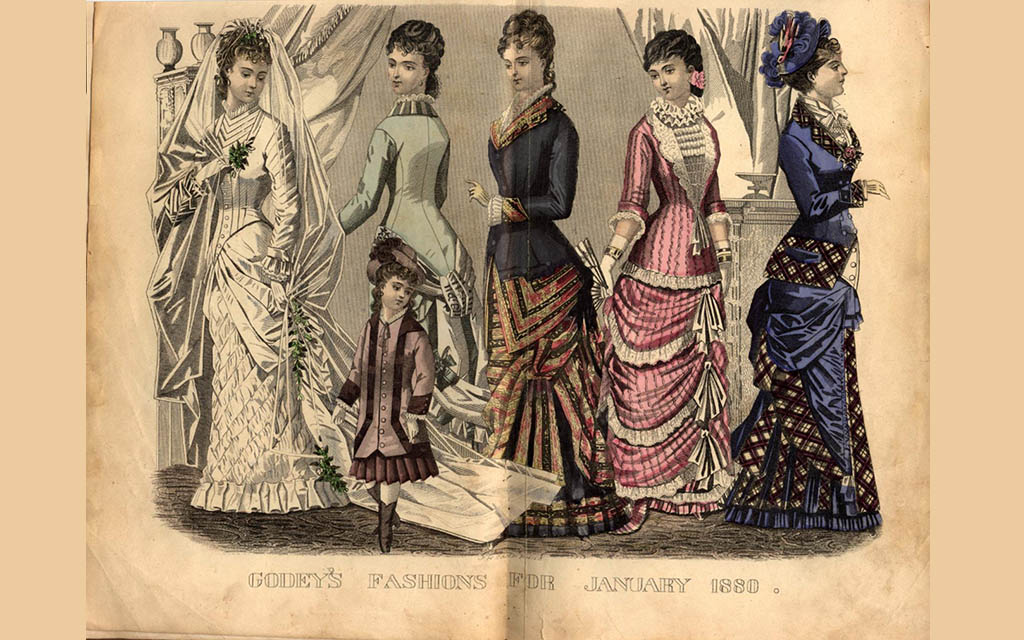

Cover Image from Godey’s Lady’s Book Volume 100 January To June 1880

Ladies’ Reading Material

On June 23, 1877, The Pittsburgh Daily Post printed a small article announcing the sale and rebranding of the most popular American magazine in circulation, Godey’s Lady’s Book. It reads, “The oldest American Monthly, ‘Godey’s Lady’s Book,’ will be transferred to new publishers in August. Mr. Godey has originated and conducted it for over half a century.” Other newspapers noted the new publishers would update the paper and ink, thereby providing a better quality reading experience to a national subscription base of over one hundred thousand households. This small announcement seems unremarkable, but the Philadelphia-based magazine was a household staple for women for over fifty years. The magazine’s editor from 1837 until 1877, Sarah Hale, was an extremely influential figure in the publishing world, especially when it came to shaping the interests and tastes of white, middle-class women all over the United States.

When Sarah Hale retired from her position as editor of Godey’s Lady’s Book in 1877, she was almost ninety years old, and she had wielded the power of the press to shape ideas and expectations of American womanhood. During the course of her lifetime, Hale championed many causes on behalf of women’s advancement in the public sphere— particularly when it came to education. In fact, her advocacy on behalf of establishing institutions of higher education for women contributed to the foundation of Vassar College in 1865. She sat on the original board of trustees and frequently corresponded with the founder, Matthew Vassar. In one of her letters to Vassar from 1860, Hale writes: “I am much interested in what I have learned respecting your plans for a new Institution, on a very liberal scale, for the Young Ladies of America […] I feel solicitous to know more of the plan, in order to make it known to the readers of the ‘Lady’s Book.’” Throughout her tenure as editor of the most widely read women’s magazine in the United States, Sarah Hale would continue to advocate for women’s education as central to their intellectual, social, spiritual, and moral development.

Imagine Godey’s Lady’s Book in a sitting room or bedroom in a house in Youngstown, Ohio. Then imagine another volume in a sitting room in a house in Lawrenceville. And then, imagine still yet another volume in a ladies’ parlor in a house in the fashionable East End—perhaps in Jane Clark’s parlor, or maybe tucked in Carrie Clark’s bedroom.

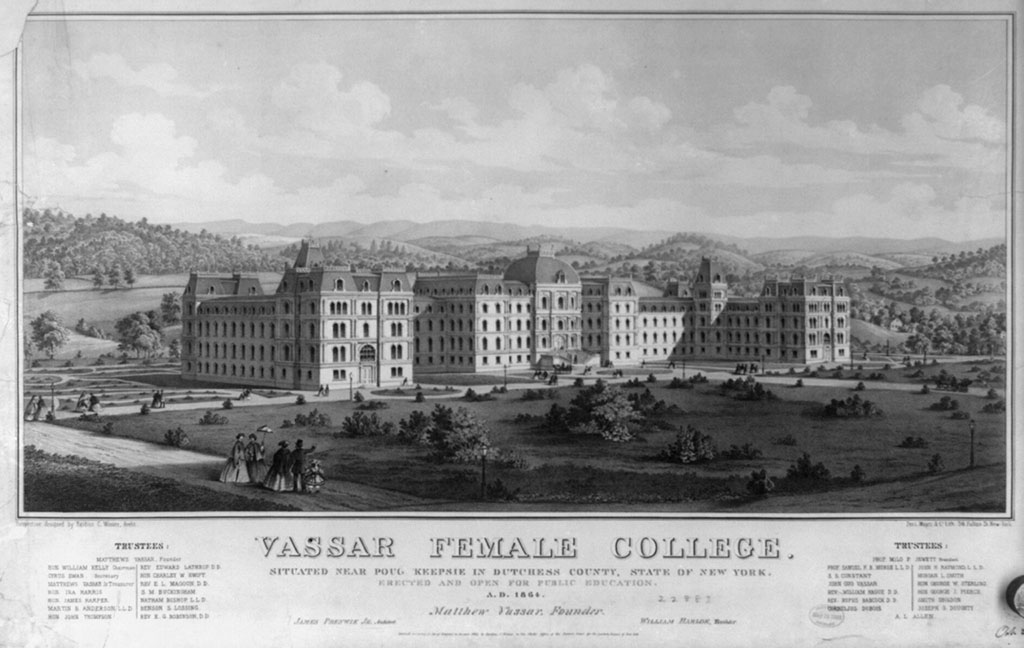

From the Library of Congress, “Vassar female college, egidius,” Ferd, Mayor & Co. lithograph.

An Education

William Clark, owner of Solar Iron Works at the corner of 35th and Railroad Streets in Lawrenceville, was in business with his son, Edward, and his brother-in-law, Charles Fownes. Founded in 1869, the Solar Iron Works manufactured iron hoops, bands, and scrolls and could employ up to two hundred men when operating at full capacity. The company developed a good reputation for producing quality iron products, and their client base stretched as far as New England. The company flourished under Clark’s leadership, and by the late 1870s, he moved his family away from the smoke, grit, and thrashing metal of dingy Lawrenceville into an extremely fashionable East End neighborhood, at the time known as Shady Land.

With all of this success, however, came new responsibilities and expectations for the family. The Clarks were, by all accounts, upwardly mobile middle-class people who aspired to prestige and influence throughout Pittsburgh. Edward Clark, the oldest son, worked with his father and was expected to assume further ownership of the factory. There were two more sons before Carrie, Frank and William, and they, too, would go on to careers at Solar Iron Works. As the oldest daughter, Carrie bore the weight of familial expectation based in advantageous marriage, involvement in appropriate charitable organizations, and maintaining a public image of domestic respectability and upstanding moral character: a guide, a beacon worthy of women’s emulation.

However, William and Jane Clark sought an atypical path for success on behalf of their daughter. In 1877, the Clarks enrolled Carrie at Vassar Preparatory School. Located in Poughkeepsie, New York, and attached to Vassar College, Vassar Preparatory enrolled girls who needed pre-collegiate training, mostly to make up for a deficit in available primary and secondary educational opportunities for women. When a course of study at Vassar Preparatory was completed, a girl could then apply and matriculate to Vassar College. According to extant records of Carrie Clark’s formal education, she completed three years of preparatory school (1877–1879) and an entire year of college (1880) before returning to Pittsburgh.

Nineteenth-century women had two routes to higher education: enroll at either coed institutions (ex. Oberlin) or women’s colleges (ex. Bryn Mawr). Women’s colleges like Vassar modeled campuses not on academic villages with separate dormitories and classrooms, but on seminaries, which were characterized by multipurpose buildings in which students could live and study under one roof. Functionally, a college like Vassar existed to not only educate the middle class’s daughters, but to facilitate their destinies as the mothers and wives who shaped the intellectual, moral, and spiritual character of great American men.

This new system of providing women with higher education equal to that of their male counterparts garnered as much acclaim as it did skepticism and derision. By 1880, 46 percent of colleges and universities in the United States admitted women, and while this statistical percentage grew and more women’s colleges opened, Vassar College in particular gained something of a radical reputation.

On June 1, 1873, the New York Times printed a scathing piece on the dangerous educational environment at Vassar: “One can fancy what sort of young ladies would come forth from a four years’ university course, when they had struggled with, day by day, and often surpassed the best minds among the young men of the country. They certainly would not be the ideals which the world had formed till now, of the most refined womanhood.” In summation, women who took courses equal in rigor to the men’s classes (often taught by the same professors as Vassar’s counterpart, Yale), would grow to be too smart, too ambitious, too worldly, and directly pose a threat to the established social order. Vassar women might do the unthinkable: reject marriage and children entirely in favor of pursuing professions.

By 1893, five years after Carrie Clark’s death, anxieties about just what kind of women went to Vassar reached new heights. The Los Angeles Times published a piece called “College Girls and Marriage: Something Wrong with Higher Education, as Half Become Old Maids,” specifically about the dangers of families sending their daughters to Vassar.

But this rigorous course of study included several semesters of Latin, Greek, German, and French, and two semesters each of mathematics (including algebra), geography, history, and rhetoric. Students could then expand their course of study to cover subjects like chemistry and biology, religious studies, and literature.

Despite the potential for resistance or pushback from others in their social circle who might question the Clarks’ decision for their daughter to receive an education, they still chose to enroll Carrie for several years. Though she did not complete her degree—at the end of the nineteenth century many women who started college never finished—Carrie returned to Pittsburgh armed with a world’s worth of ideas, inevitably and invariably shaped by the books she read, the languages she learned, the professors who taught her, and the people she met.

What was she supposed to do with this education, then? Theoretically, her education would have equipped Carrie Clark to manage a household budget, participate in important dinner conversations, cultivate a stimulating and beautiful home life full of art, music, and literature, and educate the next generation of upstanding citizens.

One very interesting detail to note here is that it does not appear that any of the other Clark children went away to school. At this time, it appears as though William and Jane Clark singled out their eldest daughter, and we do not yet know why. One tantalizing possibility lays in the now-famous Pittsburgh Daily Post article from February 29, 1884: “the new furnace at Rankin Station on the Baltimore and Ohio railroad, about [ten] miles from the city was yesterday morning christened the ‘Carrie Furnace’ in honor of Miss Carrie Clark who lit the fires and performed other baptismal services.” Out of all the possible women in the Clark and Fownes families who could assume such a publicly visible role, it was Carrie. There is an as-yet undiscovered relationship between the smart, amiable, and polished young woman equipped with a progressive, modern education and the position she took at her father’s side on the day she changed Pittsburgh’s history.

Next Time on Who Was Carrie Clark?

In the next installment of our investigation into Carrie Clark’s world, I am going to give us a closer look at her marriage to Bartlett Arkell, the birth of their son, William, and her untimely death.

Dr. Kirsten L. Paine is an educator and researcher with more than a decade of experience working in higher education. She started working for Rivers of Steel in 2017 as a tour guide at the Carrie Blast Furnaces National Historic Landmark and was inspired by the mission to preserve such a national treasure held in public trust. Kirsten is committed to the work of public humanities education in her role as Site Management Coordinator and Interpretive Specialist. By creating and facilitating public programs that make the National Heritage Area’s history come alive for the community, she believes in archival study and teaching from primary sources as vital community resources.

Dr. Kirsten L. Paine is an educator and researcher with more than a decade of experience working in higher education. She started working for Rivers of Steel in 2017 as a tour guide at the Carrie Blast Furnaces National Historic Landmark and was inspired by the mission to preserve such a national treasure held in public trust. Kirsten is committed to the work of public humanities education in her role as Site Management Coordinator and Interpretive Specialist. By creating and facilitating public programs that make the National Heritage Area’s history come alive for the community, she believes in archival study and teaching from primary sources as vital community resources.

Enjoy Dr. Kirsten L. Paine’s article? Read her description about the discovery of Carrie Clark.