Community Spotlight—Carnegie Library of Homestead at 125

The Community Spotlight series features the efforts of Rivers of Steel’s partner organizations, along with collaborative partnerships, that reflect the diversity and vibrancy of the communities within the Rivers of Steel National Heritage Area.

By Julie Silverman, Contributing Writer

A Tale 125+ Years in the Making

The Carnegie Library of Homestead is throwing a birthday bash on November 3, 2023, marking its 125th year of serving the Mon Valley. In January, the library hosted an open house to kick off events throughout the year, but the upcoming celebration will be a more formal affair. Exploring the historic halls with cocktails inspired by classic novels, partygoers, community leaders, and neighbors will enjoy entertainment and hors d’oeuvres, along with a look at the beginnings of the edifice on the hill through archival photographs and oral histories.

Homestead library was a twinkle in the eye of Andrew Carnegie as far back as 1889. Although ground would not be broken until 1896, Carnegie glanced across the river from his first Pittsburgh library in Braddock during its dedication ceremony and envisioned a repeat performance. Carnegie’s generosity was complicated. The previous year had been tumultuous in Braddock’s Edgar Thompson Works. Skilled steelworkers and managers clashed over wages. The steelworkers ultimately yielded to Carnegie’s sliding scale, and with Carnegie’s victory came the Braddock library.

Homestead’s skilled steelworkers continued to work under a union contract. By the end of June 1892, negotiations stopped, and the steelworkers were locked out of the mill. On July 6, strikers battled Pinkerton private security agents. The day brought ten deaths. Although a win for Homestead early on, with the National Guard allowing strikebreakers to work, it became a major defeat for unionizing steelworkers. Six years later, on November 4, 1898, Andrew Carnegie was fêted on the Homestead library’s opening day.

While Carnegie required communities to use public funds to subsidize the operation of his libraries, Homestead was one of the few exceptions. Operation of the libraries in Braddock, Homestead, and Duquesne were originally funded by Andrew Carnegie and his steel plants in those towns. After the sale of his business to U.S. Steel in 1901, Carnegie established a $1 million trust to support the three facilities. In the 1960s, the Braddock and Duquesne libraries were turned over to the school districts in those communities by the Board of the Endowment for the Monongahela Valley. The Homestead library is now the sole beneficiary of Carnegie’s gift.

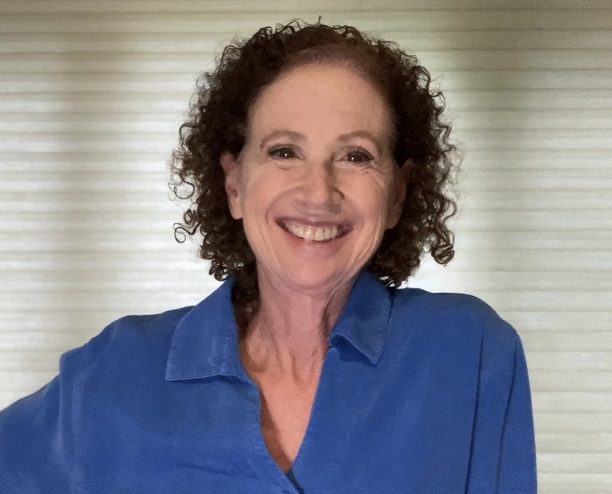

Emily Kubincanek, program coordinator for the Carnegie Library of Homestead, poses in front of images and items reflecting the community’s past.

Library Archives Tell a Different Kind of Story

Sitting with Emily Kubincanek, the library’s program coordinator, in a room that had once been the Club Parlor, it is hard to imagine the smoking area and the billiards hall that once stood here. It’s one of the rooms for which upcoming renovations will take place over the next couple of years. But Emily’s archival workshop, which contains a treasure trove of history, is in a much smaller room.

It’s rather cool, which helps keep everything preserved, as does a dehumidifier. “The library building itself does not have a central air system,” Emily said. “Many of our artifacts are in brittle condition since they’ve been here for decades in not ideal conditions. After the renovations, the collection will move to one of the centralized air-conditioned areas.”

Boxes are stacked throughout the room. On shelves are more boxes, maps, posters, old books, and trophies from different teams from the library, and surrounding community organizations, churches, and schools.

“A lot of this stuff has been untouched for years. It was just a room of . . . wonderful old things, and I didn’t know where to start.” Many items in boxes are not dated, titled, or cataloged. Several groups carefully kept this collection over the years, and Emily is the current caregiver of history. “The upkeep is expensive. I secured a grant from the Pennsylvania Historic and Museum Commission to digitize photographs, blueprints of the building and former renovations, and maps from the area. That’s helped give a purpose to what we’re doing.”

Emily started two years ago and frequently collaborates with Rivers of Steel. Both organizations hold cultural memories of similar historic times and have a great interest in educating people about local history and preservation. It’s a natural fit to work together. In the huge project of cataloging archives, Ron Baraff and Ryan Henderson, whose roles for Rivers of Steel include managing the archives, lent their expertise. “They looked at everything, saw the direction we are going in, and helped in terms of how to archive and organize in a way that people understand,” Emily said.

Emily pulls out a drawer. “These are some things that we’ve cataloged—some pictures from the Duquesne library when it opened.” The faded black and white photograph shows a Polish nationality group walking in the parade. “They did something similar when the Homestead library was opened. The building in Braddock is still there. It’s huge. It looks like a castle.”

The opening of the Duquesne Library in 1904. Image courtesy of the Carnegie Library of Homestead Archives.

She pulls out another large paper. “Here are the plans for blueprints, for renovations, proposals from different architects that were bidding to design this building, but they chose Alden and Harlow.

When we think about the three original libraries that had music halls, pools, and library spaces, Duquesne, Braddock and Homestead, we are the only one in the entire U.S. that is still running in every capacity. Braddock is renovating now, but they will no longer have their pool or athletic club. Duquesne was demolished in 1968 to make way for a new high school, which was never built,” she said.

Looking at the photos from Duquesne library evokes images of the past. In the extended shadow of the library was the Homestead mill that is also gone. “It was a complicated time as the mill closed, Emily continued. “In speaking with Ron, he talked about how people wanted it completely gone so there wouldn’t be hope that it would come back. Any remainder of the mill would be a constant reminder of that. People growing up now would love to have more historical pieces preserved. Only now do you realize how much is gone.”

“Most of this building is still operating as it was originally built. I think is a huge testament to the passionate people in the community who stepped up and fundraised after the mills no longer wanted to be part of running and funding the building. I think that is why it is still successful today.”

USX Corporation, the successor to U.S. Steel, continued to provide major support until 1988, when the corporation terminated its regular donations and community leaders from Munhall and surrounding areas formed their first public board to assume responsibility for the library. Despite the closing of the Homestead Steel Works two years earlier and the precipitous decline in employment and tax revenue, the library remained open and operational with grants secured by community volunteers and the investment income from Carnegie’s endowment.

Girls in the 1940s relax while reading at the library. Courtesy of the Friends of the Library Collection, Carnegie Library of Homestead Archives.

An Oral History Project Recalls Formative Experiences

A part of the 125th Anniversary celebration is the Oral History Project. Emily has been talking with people about their experiences growing up in Munhall, Homestead, Whitaker, and West Homestead about how the library has had an impact on them. It’s a one-on-one way to understand how the library has changed over the years, in the context of how the area has changed. Twenty-seven interviews so far have netted stories about growing up around the mill and even learning to swim at the library.

Before the library, Homestead didn’t have a public pool. There was a pool—closed in 1973—in nearby Kennywood Park. Early on many people swam in the river. The pool in the Carnegie Library of Homestead filled a gap and created champions. Along with supervising other sports, Jack Scarry also became the swim coach at the pool in 1918. He trained children of the mill families and became known as “The Maker of Champions.” The Homestead Library Boys Swimming League boasts a trophy from a 1926–27 contest. Lenore Kight and Anna Mae Gorman medaled in the 1932 and 1936 Olympics. Many long-time Homesteaders have memories of Jack Scarry teaching them how to swim. Anna Mae Gorman continued to swim at the library into her 90s.

The pool—open to the public from the start—and the accompanying suite of showers provided a luxury service for the community, paired with a necessary one. A majority of the people living in the ward would not have had their own bathrooms or bathing comforts, which would have been typical in mill neighborhoods at that time. Swimmers were required to shower before hopping in the pool.

These facilities would have served them, and through the years, mill workers served the facility. “A lot of the repairs were done by millworkers as opposed to outside contractors,” Emily said. “They were brought up from the steel mills to fix anything from a clogged sink to the boiler system. There was a blueprint for fixing the pool boiler, and it was stamped with a Carnegie Steel seal. I talked with a few former workers who worked in the mill. They were engineers sent here to work on specific projects.”

Today, the Athletic Club continues to serve the community, offering affordable access to fitness, including workout classes, weight room activities, swimming in the pool, and use of the basketball court. Silver sneakers programs for seniors, sport leagues and swimming lessons for kids, and discounted programs for teens provide all ages with opportunities to be fit and social.

The Young Adult Reading Room at the Carnegie Library of Homestead today.

The Hub of the Community

“Recognizing the history of the area and how people received the library is important,” Emily said. “The perspective of the strike didn’t just go away once the library opened.” Even today, the treatment of the workers during the lockout and strike is recalled when considering the legacy of Carnegie’s institutions. Many families were apprehensive about the location of the library because it sat high on the hill, away from the ward where most families lived. However, part of what made the library accessible and attractive to the community was what happened before the library opened.

In going through the archives, Emily discovered that even before the opening celebration, the first superintendent, W. S. Bullock, and librarian Helen Sperry “took applications to get a library card and physically put them in the stores on Eighth Avenue. Before the actual dedication and Andrew Carnegie’s arrival, they were already lending books, putting programs in the Music Hall, and spreading the word in the newspapers about the community work they were doing. I believe these two were a huge part of why people could overlook Andrew Carnegie’s affiliation with the building. Their continued passion laid the groundwork for why the library continues to be relevant and successful even today.”

The Music Hall invested in the community early on. In going through the first twenty years of scanned programs, Emily found that not only did the library boast its own band, but they also held chorus concerts. Carnegie Steel hosted safety presentations. Munhall High School held their commencement programs in the hall and held plays for seniors citizens. The hall hosted traveling symphonies, educational lectures, and magicians. It was utilized by community churches. All cultural activities were free to the public unless the hall hosted a benefit performance.

The Homestead Grays used the hall for fundraisers. However, at that time, around 1915, the hall was still segregated. The pool and athletic club continued to be segregated for an even longer period. In some of the oral histories, Black Americans who grew up in the area stated they never felt welcome in the athletic club or gym due to the historical segregation. The library, however, was always a place that welcomed everyone.

When the mills closed in Homestead, it marked the beginning of change for how the Music Hall was used. The steel mill, which previously used it constantly, did not have a need to hold events here. With declining populations, Munhall High School closed, and so ended the annual commencements. Churches grew smaller. Big reviews were no longer popular. The Hall was underutilized, being used only a handful of times throughout each year. It grew dark and dusty.

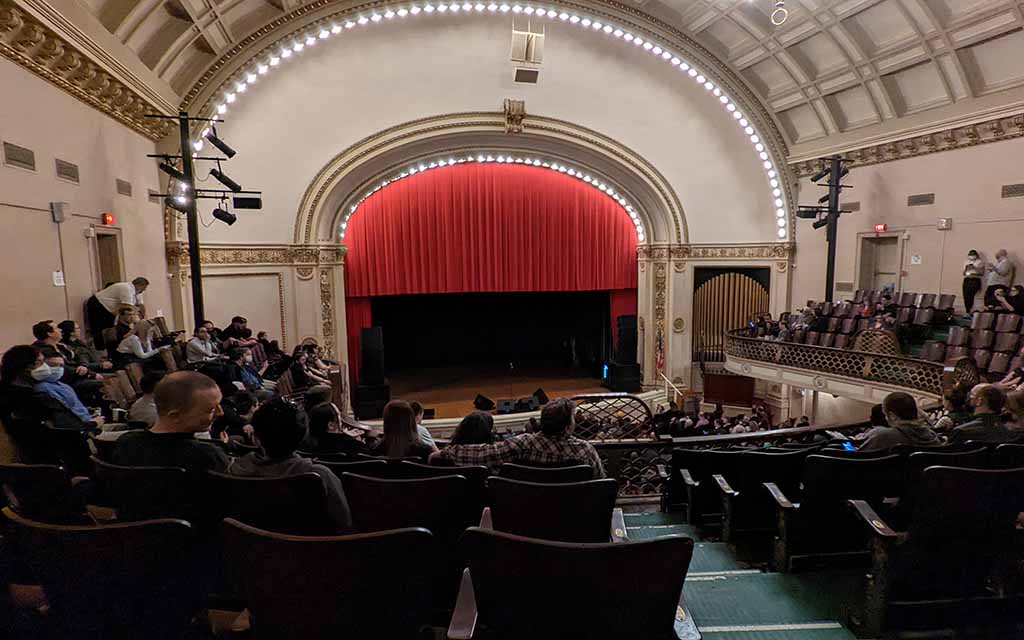

The Music Hall at the Carnegie Library of Homestead, in March 2022, before a spoken word event by Henry Rollins.

In the early 2000s, a decision was made by community leaders and the board of directors to resurrect the use of the hall by hosting cultural entertainment—bands and comedians. It began to promote tourism to the Mon Valley so fans from across the state and across the country could enjoy performances by nationally renowned artists. The first show was Patti Smith on August 1, 2007. At the beginning, twenty to thirty shows were booked each year. Now, tens of thousands of visitors enjoy sixty to eighty performances annually. The acoustics remained as good as when the Music Hall first opened. The wooden seats however, although good for sound, were losing popularity. They were originally designed for the average American who was 5’10” and around 150 pounds. Replacing the seats is part of the next phase of historic renovations in the music hall, which is set to commence in June 2024.

The library’s services were originally created to support and benefit steel mill families. Today, libraries look different, particularly after the distancing during the first years of the pandemic. “When I started all the programs were virtual or at home,” said Emily. “Although the Athletic Club and Music Hall attendance has bounced back, it’s been challenging to draw people to come back to enjoy programs in person at the library. Thankfully, we’re seeing a huge jump in attendance just this past year.”

Emily listens to the oral histories and hears that many kids growing up had not realized how special it was to have a library with a pool, a music hall, and a gym, not until they saw libraries elsewhere. Nevertheless, it was always their library, not a library with a tinge or taint to it. Emily says, “You will always have the connection to that past, but that’s not all of what the library came to be. You continue to listen to what people are wanting and missing and try to fill that need any way you can.”

“Listening to oral histories shows the full effect of a library,” Emily continued. “Older adults, having visited as children, have said they wouldn’t be the person they are today if they hadn’t come to the library as much as they did when they were younger. It gives an opportunity to see how the library transformed the person they came to be.”

The Munhall letterman sweater that was recently donated to the library’s collection.

Just a month ago, a box arrived for Emily; in it was a letterman jacket from Munhall High School. Munhall High School had been demolished when it merged with Homestead High School, which is now Steel Valley High. Along with the maroon jacket are programs from when the high school used the Music Hall.

“Some things that happened in our library or things that have happened in the community have nowhere else to be preserved other than here.”

Julie Silverman is a museum educator, tour facilitator, and storyteller of astronomy and history for various Pittsburgh area organizations, including Rivers of Steel. A Chatham University 2020 MFA graduate, her writing is most often found under the by-line of JL Silverman. Occasionally, under the name of Julia, she has been seen on TV.

This is her first article published for Rivers of Steel. If you’d like to read more of our Community Spotlight stories, click here.