Community Spotlight—The Wandering Wall at The Ruins Project

The Ruins Project is a long-term collaborative mosaic art installation amidst the ruins of a former coal mine in Fayette County, Pennsylvania. Its creator is Rachel Sager, a frequent Rivers of Steel collaborator who operates the Sager Mosaics Studio located near mile marker 104 on the Great Allegheny Passage. The Ruins Project is an exceptional attraction in the Rivers of Steel National Heritage Area, a destination for art lovers, trail-goers, and the heritage-curious. The Wandering Wall is the latest addition to the outdoor gallery space.

By Julie Silverman, Contributing Writer

Artful Divisions of Space

I walk over The Jeffrey Luce Sager Memorial Bridge, my focus on the grey wall ahead of me. It is adorned with a circular mosaic to the left of where there was once a door. The empty frame remains, punctuated in yellow mosaic. A circular mosaic (crafted by Mercer artist Deb Englebaugh) on a distant wall echoes the circular design by the door. To the right it reads: The Ruins Project.

Rachel Sager at the doorway into The Ruins Project.

This locale was once the booming coal town of Whitsett, Pennsylvania. Train tracks zippered the flat strip of land between the hillside and the Youghiogheny River. Now, cyclists pedal by on the Great Allegheny Passage trail, which begins in Pittsburgh and stretches 150 miles to Cumberland, Maryland.

These walls are the remains of Pennsylvania Coal Company’s Banning #2 coal mine. Mining began here in 1893, and this site became the most productive of the eighteen mines dotting the Youghiogheny Valley. As I walk through the ruins, coal crunches under my feet. It permeates the site, as do the mosaics of more than two hundred and fifty artists.

At a far wall, I find Rachel Sager with Wendy Casperson, paint brushes in hand, with welcoming smiles. Rachel is the owner and creator of The Ruins Project. Her mosaics studio, Sager Mosaics, is just across the road near marker 104 of the Great Allegheny Passage.

Rachel explains the piece they are working on. “Normally, this would be the last piece of art you would talk about if you were taking a tour. It’s a symbol of everything that is happening here, a Venn diagram of The Ruins Project.” She gestures toward the mosaic. “This circle is the artists. This circle is the coal miners. And this,” she points to the intersection of the two circles, “is The Ruins Project, where those two kinds of people overlap.”

The overlap is where past, present, and future converge. A time machine, if you will, of the land itself in which the coal formed, of the men who mined, of the artists bridging gaps on a concrete canvas renewed, and of those who pass along the stories. The idea of time is imperative in Rachel’s work.

Rachel Sager’s studio along the Great Allegheny Passage.

We are on the bike path side of The Ruins, which is exposed to the public view. The bridge I crossed, which is now the formal entrance, was named in memory of Rachel’s father. He had plans to build it and passed away before he could. Hundreds of donations in his honor, and the hands of Dave Svonavec of Somerset, completed the bridge in 2022. A chain can be placed across the bridge, along with a “Do Not Enter” sign, to clearly separate The Ruins from public spaces. Where we are standing is within easy sight of the cyclists. The hill sloping to the bike path has been used by those climbing up to work and was the previous route for guests, but curious wanderers also find their way in. The Ruins has become a much more visible presence.

“The longer The Ruins is here and the more notoriety it gets, the more people want to sneak in and take a look,” Rachel shared. “When you think of places like Fallingwater or other museums, they have entrances and boundaries. It’s clear it is a place that you have to get in to, you don’t just wander in to. That’s why it’s called The Wandering Wall. It keeps out the wanderers, but it also wanders itself.”

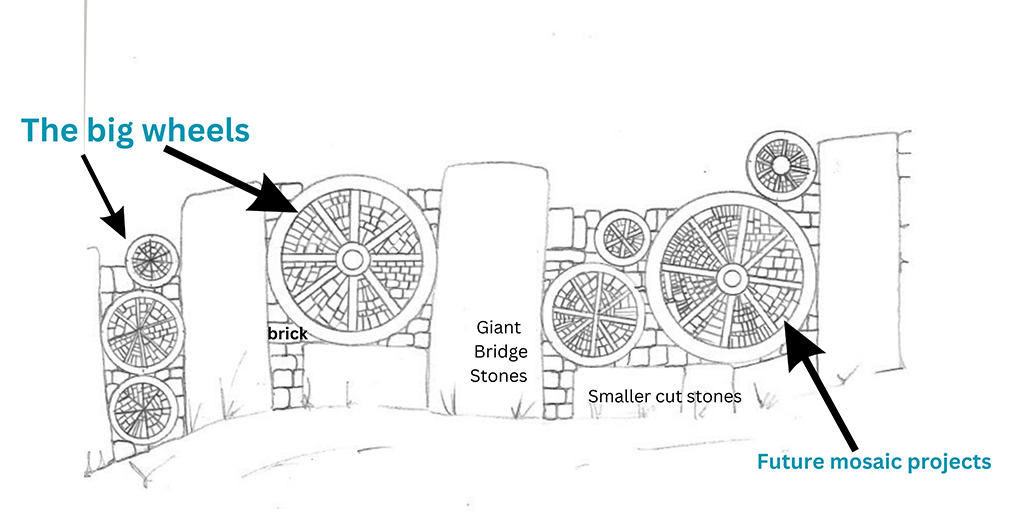

The Wandering Wall in progress.

The Wandering Wall, A Work in Progress

Steve Guinn

Rachel’s inspiration for The Wandering Wall came from her friend and mentor of twenty-five years, Steve Guinn. He was an industrial psychologist, but also an artist, writer, poet, and avid fly fisherman, among many other interests. Steve Guinn, about the same age as her father, passed away in 2021, just one year after Rachel’s father. His mentorship propelled her to do the colossal project, The Wandering Wall. “We talked philosophy for years and how to see the big picture, just like my Dad did. I think about him with every little step of the wall that we build,” Rachel said. Steve’s wife Kathleen and daughter Shanan began the early sponsorship of the wall, while Rivers of Steel provided administrative support to assist in the project’s development.

As The Wandering Wall aims to make the site look more official, it is solving several problems. “The Ruins are just full of problems that are fun to solve,” Rachel laughs. There are issues of safety, protection of the arts, and the fact that this is private property. “Robert and I live here. Our home is here. That presents us with a challenge to have a life amidst this semipublic place that I’ve created,” she says.

There was the challenge of what the wall would look like. Rachel continued, “I didn’t want to put up barbed wire. That would not have been in keeping with the arts and the character of the whole place. I wanted to have a beautiful barrier that is inviting and also keeps wanderers out. It’s a double message. Robert says that it’s not going to keep people out, it’s going to make them want to come in!”

The design vision Rachel came up with was a wall of giant stones and giant wheels. The Wandering Wall construction began with arranging nine enormous Stonehenge-sized stones weighing about two tons each. Her brother’s industrial sized tractor strained to lift and move the behemoths. Looking down from The Ruins above, the granite rocks appear like stepping stones, meandering along the shrub line. From eye level they are majestic titans. The gaps between them are being filled with big metal wheels and gears, engaging with the stone and metal gears that appear layered within the art of The Ruins. “The circle metaphor is repeated everywhere. It is an archetypal image that I keep returning to in my art,” Rachel said.

Every aspect of the wall aims to aesthetically mesh with The Ruins. The stones were once part of an old railroad bridge. The metal represents the industrial history of the region. Agricultural equipment will find its way among the wheels and rock. All materials are chosen to be site specific, representing the mine operations and the industry that the coal supported.

With the hardest part of the wall complete, the stones set in their places, next steps are to pour concrete around each stone. Then wheels will be nestled in between, with some of the wheels being stacked higher than the stones. Future ideas include installing mosaic inside wheel spokes. By conscious design, The Wandering Wall is a work in progress. A piece that, as Rachel says, “Will take us years to finish. I hope to have the wheels installed before the snow flies.”

Honoring What Was

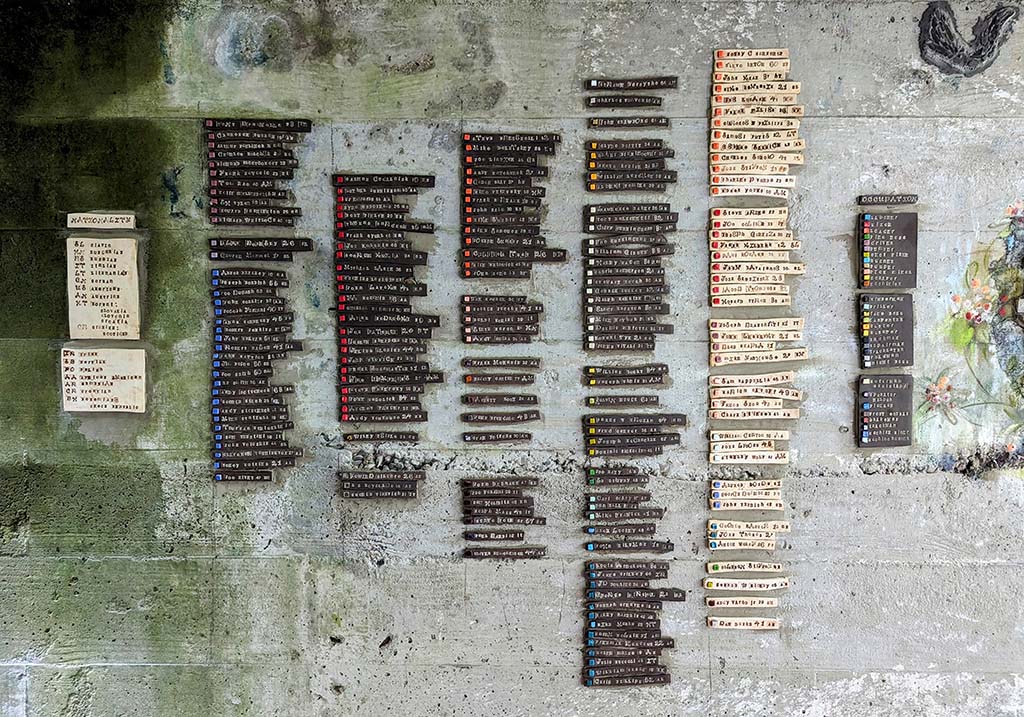

A project coming to fruition brings us back to Rachel’s first rule of The Ruins, to Honor What Was. As the entrance bridge and The Wandering Wall honor those who came before, so, too, is a list of two-hundred-plus miners who worked at Banning #2. An artist in Florida, Janis Nunez, created color-coded name plates for the miners. Each plaque designates where the miner was from, how old they were, what their job was in the mine, and if an injury or a fatality occurred.

We walk, crunching over coal, to the Memorial Chapel where Erika Johnson, the tour program director for The Ruins, and Wendy are looking at the ceramic tiles. The project has been in the works for years. The pieces have finally arrived. Rachel sighs as she looks at the tabletop of names lined up by color-coded categories. “It’s one thing to look at that list on a computer. You don’t see what two-hundred-plus names looks like until you see it physically in front of you.” She lightly touches the plaques.

Roll call for the miners of Banning #2.

“These are the deaths,” she says. “The ones in white are the ones who were killed in this coal mine.” Rachel points out the laborers. The miners, who were in the mine digging the coal. Loaders, with the job of shoveling into the coal cart. Machinists, with the higher-paid jobs. Shot-firers, who dealt with explosives. I wonder that the category of loaders has more fatalities than the others. “I expect this would have something to do with loading the cars on the rails. I think legs got cut off a lot. Maybe they would lose their leg and then die,” she contemplates. A hope is that the list will help find the families of the miners—to honor what was and help research what may have been.

It is beautifully done and organized, exquisite and sad and celebratory . . . we are quiet looking at the tiles. I am reminded of Rachel saying, “The power of mosaic, pieces and pieces of lives. The stories that we’re telling here are timeless, human, and geologic.” Woven through this day and woven through The Ruins is remembrance and rejuvenation, voice given to those who came before.

About The Community Spotlight Series

The Community Spotlight series features the efforts of Rivers of Steel’s partner organizations, along with collaborative partnerships, that reflect the diversity and vibrancy of the communities within the Rivers of Steel National Heritage Area.

Julie Silverman is a museum educator, tour facilitator, and storyteller of astronomy and history for various Pittsburgh area organizations, including Rivers of Steel. A Chatham University 2020 MFA graduate, her writing is most often found under the by-line of JL Silverman. Occasionally, under the name of Julia, she has been seen on TV.

If you’d like to read more of our Community Spotlight stories, click here.