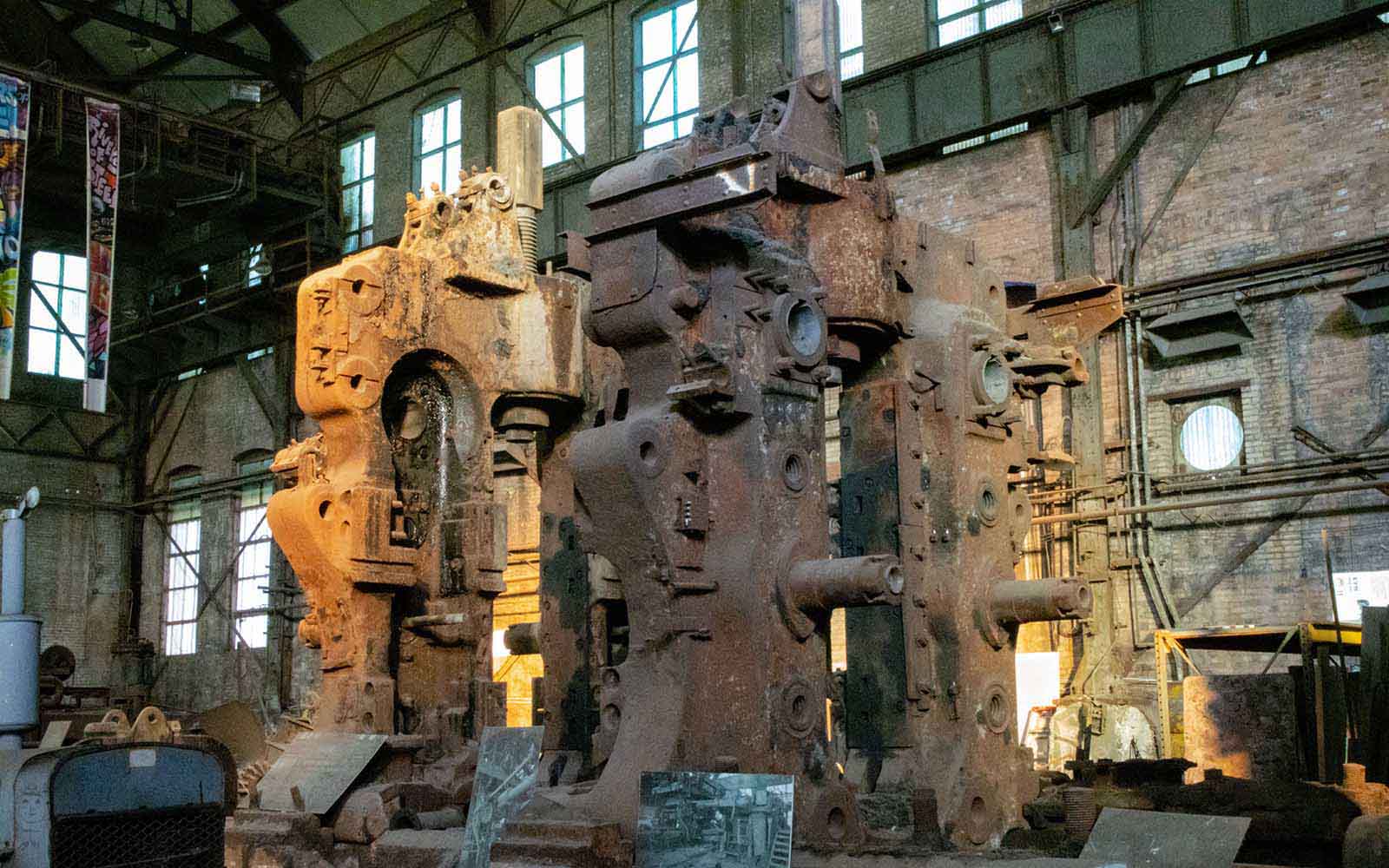

The 48-inch Universal Plate Mill as it appeared in the fall of 2022, immediately prior to recent preservation efforts.

The Historic Preservation of the 48-Inch Universal Plate Mill

After spending decades in storage, the 48-inch Universal Plate Mill from the Homestead Works is undergoing historic preservation work with support from an array of funders and a collective of workers. Since May is National Preservation Month, we’re excited to take this opportunity to share some of the important work that is currently going on, outside of public view, at the Carrie Blast Furnaces National Historic Landmark.

By Lynne Squilla, Contributing Writer

The 48-Inch Mill, a Part of Our Nation’s Story

It rolled out the steel that built the Empire State Building in New York City, the Golden Gate Bridge in San Francisco, and scores of other iconic American structures in its 80-year history from 1899 to 1979.

Known as the 48-inch Universal Plate Mill—and originally located at U.S. Steel’s Homestead Works—it was one of the mighty workhorses that defined the Steel Valley. When steel was king in the region, the mill churned out slabs of thousand-degree metal that became rolled plates used in large-scale construction.

Today, it sits in pieces inside the Blowing Engine House, part of the Carrie Blast Furnaces National Historic Landmark, waiting to be cleaned, restored, and rebuilt to recall its former glory. Even in pieces, it is the only surviving steam-powered rolling mill in the nation—and even the world. When restoration is complete, it will be the centerpiece of an ambitious visitor center and museum with exhibition and artifact space at the Carrie Blast Furnaces. Before then, it will help train a small workforce in crucial industrial restoration skills.

The task of resurrecting the 48-inch Mill is no small feat. However, the dedicated team at Rivers of Steel is undeterred, armed with the energy, vision, and expertise to make it happen. The effort is already in motion, fueled by funding from key grants and private foundations.

Rivers of Steel’s Director of Historic Resources & Facilities, Ron Baraff.

“This is a really exciting time,” says Ron Baraff, director of historic resources and facilities for Rivers of Steel. “All those years of pushing, working to save and preserve structures and artifacts from the steel industry, hoping to do all those things people thought were just too big to do—now, they’re all coming to fruition. And the restoration of the 48-inch Mill is so vital to telling the history of this area.”

Reassembling the 48-Inch Mill

Baraff describes the task of reassembling the mill as a monumental challenge, akin to constructing a massive toy model without complete instructions. The pieces, including the main crankshaft weighing up to 132,000 pounds, present a significant logistical challenge. With only a handful of photos and drawings as references and perhaps no living steel worker with firsthand knowledge, the restoration project requires a unique blend of expertise and dedication.

Rick Rowlands with the crankshaft from the 48-inch Mill when it was being moved to Carrie a decade ago.

Enter Rick Rowlands, the project manager heading up the mill rebuild for Rivers of Steel. As the executive director of Youngstown Steel Heritage, Rick became the only nationwide expert on old steam-powered rolling mills by restoring the Tod engine of a rolling mill in Youngstown, Ohio, and poring over the existing documentation on Homestead’s 48-inch Mill.

“Rick is an iron, steel, and railroad savant. He kind of showed up at Rivers of Steel’s doorstep like a feral cat,” Baraff laughs. Rowlands started doing modest restoration projects at the Carrie Blast Furnaces site, but upon hearing about the 48-inch Mill, he told Baraff, “You know, I love blast furnaces, but I really love rolling mills!”

Rowlands explains, “The best way of learning something is because you have to know it. There are two parts to this mill: The first half is the steam engine restoration, which will be completed by the end of 2024—then we’ll switch to the actual mill.”

A sign hangs on the 48-inch mill that acknowledges support from the Historic Preservation Fund.

Assembling the Resources

After more than thirty years of storing the mill parts, hoping for the day when it could be put back together, Rivers of Steel received a prestigious Save America’s Treasures grant from the Institute of Museum and Library Services to launch this three-year restoration effort. Rivers of Steel made the case to save this vast historical artifact that tells the important story of how regional steelmaking was pivotal to building our nation. In a separate project, with support from the Hillman Foundation, a second Save America’s Treasures grant, and a Redevelopment Assistance Capital Program (RACP) grant from the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, Rivers of Steel is working to stabilize and restore the Blowing Engine House, the building where the 48-Inch Mill will permanently reside.

Rivers of Steel’s Facilities Operations Director & Construction Project Manager, Adam Taylor.

Working on the massive mill rebuild is a dedicated crew comprised of Adam Taylor, Rivers of Steel’s facilities operations director & construction project manager, and new recruits Malayna Arambula and Derek Stein. Machinist Chad Fetternick was also contracted to assist Century Steel and DCI Field Services with the heavy lifting and cement pouring.

The first step was for Adam Taylor to locate and purchase special equipment for the job—things like a sixty-ton crane and large lathe—and to create a machine shop for fabricating essential parts. All of this equipment will remain onsite at Carrie for this and future projects. While most of the enormous mill and engine parts survived intact, smaller pieces went missing, and others must be repaired or completely remade.

“We have to make things like five-inch bolts, parts of shafts, and keyways that we can’t just go out and buy somewhere,” says Taylor, a trained millwright working in tandem with Rowlands to supervise the efforts and oversee the recruits.

Malayna Arambula and Derek Stein came through a Rivers of Steel pilot workforce development project in the summer of 2023, funded by the Department of Conservation and National Resources (DCNR). They were both interns in that program and were charged with doing some of the gritty prep work for this project. With funding from several private foundations and public sources to support further workforce development, Arambula was hired full-time this spring. Stein was hired part-time as maintenance crew to assist with the mill and engine rebuild, among other tasks.

Arambula and Stein will be learning on the job, doing everything from cleaning decades of grease, dirt, and corrosion from parts to painting, repairing, or machining new parts. They will also learn how the giant pieces will be lifted into place and even help with the concrete work required to support the massive structure. Stein has some machinist experience, and Arambula operated heavy machinery and did welding during her time in the Coast Guard.

“It’s kind of like the old days,” says Rowlands about Arambula and Stein, “where you’d come to the plant as an apprentice and get put onto different jobs to assist and do a little bit of everything.”

The workforce development initiative is part of Rivers of Steel’s ongoing commitment to developing a regional labor force of people who will have the skills to help with industrial restoration projects elsewhere in the country or who can apply what they have learned to other, more conventional jobs.

“This project also trains them in fast pivoting—being able to switch gears, to envision and problem-solve,” adds Baraff.

A film by the Steel Industry Heritage Task Force, the organization that evolved to become the Rivers of Steel Heritage Corporation, which details the dismantling of the 48-Inch Universal Plate Mill at the former Homestead Works in 1990.

The 48-Inch Mill’s Post-Homestead Journey

The fact that this mill and engine were salvaged and stored for decades with most of the parts intact is nothing short of miraculous. Its long, circuitous journey to its permanent home at Carrie is equally incredible.

Augie Carlino, the president and CEO of Rivers of Steel, has been there since the beginning of the mill’s resurrection story—back in the days before Rivers of Steel was even established. In the late 1980s, the Steel Industry Heritage Task Force, which later evolved into Rivers of Steel, operated under the Mon Valley Initiative and fought to save some portion of the vast steelworks in the area after the collapse of Big Steel. The Smithsonian Institution identified the 48-inch rolling mill as the last of its kind in the world. Permission was granted in 1990 to save the mill, and it was a three-month-long challenge just getting it dismantled.

Carlino was onsite in Homestead as two massive cranes tilted in the struggle to lift the foundation elements of the mill. Standing next to him was the mill’s last foreman, Leonard Fleming.

“Leonard was this humble, soft-spoken, elderly guy who was foreman from the 1940s to the end. He was there to record some oral history about the mill,” says Carlino. “Suddenly, he starts yelling, ‘Mr. Carlino, they’re not doing it right!’—meaning how they were taking it apart. At that point, I shouted out to shut the work down.”

The work stopped. The original blueprints were consulted, and they contradicted the foreman’s advice. Fleming then explained that the drawings were intentionally not modified during the 1940s as a form of job security for the older workers. Many World War II GIs returned to the mill for jobs, but only the old-timers knew how the mill actually went together.

“So the crew went back to work using Leonard’s memory, and the mill came apart as he said,” adds Carlino.

Following dismantling, the 900 tons of mill parts were hauled to an old Westinghouse Electric site at RIDC’s Keystone Commons in Turtle Creek, where they were generously stored for free for roughly five years until that space was needed for new development. Once more, the mass of mill and engine pieces were transported, this time up the valley to Trafford, which cost Rivers of Steel a considerable amount in storage fees.

Ron Baraff came on board in 1998 and recalls seeing the mill “in hundreds of pieces, very few labels, some parts with trees growing through them—crazy, strewn about. It was a daunting set of pieces. We thought, ‘How are we going to do this?’”

In 2013, Rivers of Steel secured funds from the Colcom Foundation to finally move the parts to Carrie, a site Rivers of Steel had begun maintaining in 2010 via a long-term lease agreement with Allegheny County. Three years later, after addressing the landmark site’s most urgent preservation needs, Rivers of Steel brought the 48-inch Mill to its new home inside the Blowing Engine House at the Furnaces—and there were just enough funds left to do some start-up prep.

Rick Rowlands documented the process of bringing the 48-inch mill to the Blowing Engine House. See his flickr photo album.

“In 2014, Rick Rowlands did some basic assembly getting the roll stands and cylinders in place, but we quickly ran out of funds,” recalls Baraff. A decade later, the DCNR and Save America’s Treasures grants kick-started the real work of training, preservation, and rebuilding. The team can now reassemble the roll stands, rolling tables, drive mechanism, and steam engine.

In Rowlands’ opinion, “The building part is easy. We’ll figure it out and make it happen. Each piece is a little challenge to overcome. The hardest part is finding the money. The rest of it is just fun! I get up each day and beat my head against this heavy machinery and couldn’t be happier!”

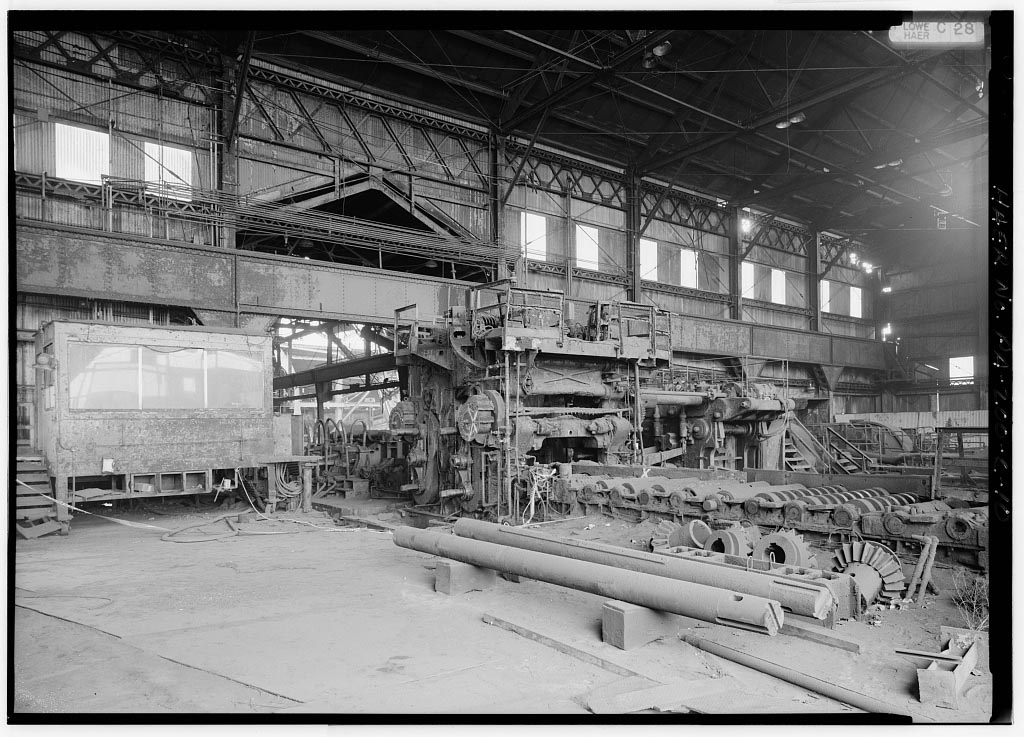

A Library of Congress image of the general interior view of the 48-inch Mill at the U.S. Steel Homestead Works.

The Work of the 48-Inch Mill

When it operated at its original location on the Monongahela River in Homestead, the mill was housed in a 60’x150‘x75’ steel-frame building with riveted Fink trusses and a monitor roof. Corrugated metal covered the roof and sides with a crane way on the east and north. In addition to the mill and its engine, the building also contained an operator’s pulpit, a scale pit, and a parts storage rack.

The rolling mill was fed steel ingots that were heated to a minimum of 1,100 degrees, depending on the product required, and would roll out long plates of finished metal up to 100 feet long. The Mill’s name is a designation of the maximum width of the plate that could be extruded, with varying widths up to a maximum of 48 inches. It rolled steel slabs up to two inches thick under extreme force and pressure, which also cleaned and eliminated scale that would cause surface defects. Hot rolling produced high-quality steel that was stronger and more formable and weldable than that produced using other methods.

In its early days, the mill was driven by a steam engine rated in the tens of thousands of horsepower—easily the largest engine in the country and perhaps the world in the early part of the twentieth century. It made a constant, thundering, puffing sound that could be heard for miles.

A rendering of what the completed 48-inch Mill will look like in the Blowing Engine House, after both have completed their historic preservation journeys.

The Layers of Significance of the 48-Inch Mill

When completed, the restored mill and engine will take up almost 23-thousand square feet— roughly one-third—of the Blowing Engine House.

Though the finished, restored 48-Inch Mill will not be fully functional, the Rivers of Steel team plans to make certain parts movable, such as the rollers and crankshaft, so that the public can get a sense of the power and majesty of this state-of-the-art technology in its heyday.

When this behemoth ruled the Mon Valley, only employees were allowed near it. Ron Baraff elaborates: “In a few years, people will be able to be right on top of this thing, at angles you’d only see if you had worked in the mill way back. This project ties together production, American ingenuity, and the impact of what was produced in this region. Beyond saving the Carrie Furnaces, it’s a real feather in our cap to restore this 48-inch Mill!”

“This is a pretty important piece in terms of technology and from an engineering point of view,” says Adam Taylor. “This is it. This is the last one in existence.”

Rick Rowlands adds: “Tens of thousands of people spent their lives building and working in this mill. They had their own communities around it. Then it all closed down, and you have these empty fields. Who were these people, and how did they do this? I like to think I’ve helped keep something around of those people and their lives.”

Baraff, Rowlands, Taylor, and the team realize that this is a labor of love and pride in the region, with their desire to accomplish the nearly impossible. Helping preserve and continue to tell the story of the steel industry in the Mon Valley with the 48-inch Universal Plate Mill at the Carrie Blast Furnaces will be priceless for future generations to experience.

Lynne Squilla is a skilled and creative storyteller. She honed her craft as a writer and producer / director of original scripts, documentaries, articles, web content, stage, and other live presentations. While her work has taken her across the globe, she’s rooted in the Mt. Washington neighborhood of Pittsburgh, and has a passion for sharing stories about our region’s past.

Check out Lynne’s previous article on the Intercollegiate Iron Pour.