Norma Ryan, a Remembrance—1931 – 2024

By Julie Silverman, Contributing Writer

Augie Carlino’s first encounter with Norma Marcolini Ryan was through food, which is not surprising if you’re of Italian heritage.

“Norma found out I was Italian,” said Augie, president and CEO of Rivers of Steel, “which isn’t hard to discover with my last name. So she invited me down to Brownsville for lunch. She made polenta for me in the old-school—the traditional—way, the way my grandmother used to make it. I hadn’t had it for years, since my grandmother passed away, and Norma wasn’t sure if I would like her version. It was just like my grandmother had made the polenta! That’s how spot on it was. I was just blown away. And that’s how I met Norma.”

In the early 1990s, the Mon Valley Initiative (MVI) was housing the Steel Industry Heritage Task Force, as Rivers of Steel had yet to become its own nonprofit. At that time, many of the MVI communities were working together to create a heritage area in southwestern Pennsylvania.

Brownsville, a former industrial town, was legendary. In the 1700s and 1800s, it was a booming and bustling hub of transportation and industry. Starting as a trading post along a well-worn Native American trail, its location on the Monongahela River made it advantageous to steamboat and barge building. When George Washington and Thomas Jefferson planned for the National Road to go through ninety miles of western Pennsylvania, Brownsville’s status as a hub for western expansion was sealed. Anyone heading into the western frontier of early America headed through Brownsville.

For those who knew her, Norma Ryan was the modern-day heart and soul of Brownsville. When she was growing up, Brownsville was lively and energetic. The town was still the intersection of railroad traffic, coal and coke transportation, barge making, and the National Road. Later in life, Norma would tell stories of the downtown sidewalks being so crowded that you had to step into the street to get around people.

Then things changed. As the steel mills and coal mines in the region put people out of work, stores began to close, and as it is in so many industrial towns, properties became neglected. Norma stepped slightly away from her long career as a beautician at Norma’s Beauty Salon to become a founding member of Brownsville Area Revitalization Corp (BARC), whose mission it is to achieve economic development through historic preservation, heritage tourism, outdoor recreation, community stewardship, education, youth advancement, and the arts.

Joe Barantovich, a community advocate for Brownsville and a collaborator with Norma, said, “She wanted to save every building. She thought they all could be saved, and she wanted the town to be the town she remembered.”

It wasn’t only the industry downturn that blighted Brownsville. In the early 1990s, Pennsylvania was considering riverboat gambling. A developer who wanted to capitalize on the idea bought more than 100 properties—some for only a dollar that were still in good condition. Riverboat gambling gave way to land-based casinos, and the developer’s plans for the buildings were scuttled.

Barantovich said, “The train station, which is called Union Station, was purchased. One day people were working there, and the next day the doors were locked. That’s how quick it was. Family photographs are still on the desks. The developer bought basically the whole downtown and then just let it sit. Norma was adamant about saving the unique architecture of every building.”

Barantovich leads Brownsville’s Perennial Project, a successful effort of planting flowers around the downtown area and creating an annual community project of beautification events and art installation (a project that has been supported by Rivers of Steel’s Mini-Grant program). But it was the Perennial Project’s Portals collaboration with local students that captured Norma’s memories of traveling to Kennywood via Union Station, combining that recollection with virtual reality.

“We kind of butted heads sometimes,” Barantovich laughed. “You can’t save all of the buildings, and we did lose a couple of really nice ones. But Norma was bound and determined to get things done. She had her vision.”

Carlino said, “Sure, she and Joe often disagreed, but they worked together for the betterment of the town. Norma wasn’t the type of person to hold a grudge. She always wanted to find a way to work with you.”

When the MVI and BARC were working on the renovations of the Flatiron Building, Rivers of Steel helped with interpretive planning and exhibits. It was more than a ten-year process to restore the building. Currently, the Flatiron Building also houses a museum for Frank Melega, a local artist and good friend of Norma’s. Melega was a coal miner’s son, and Norma was a coal miner’s daughter. His portrayals of life in southwestern Pennsylvania in the height of the coal and coke era became nationally famous.

Norma once said, “I’ve always been civic minded, always interested in people.” Add to that her drive and determination to revitalize Brownsville, and it might have seemed a natural progression for someone to suggest that Norma run for mayor. She was serving on the borough council and overseeing restoration of the Flatiron Building when the advice propelled her into history. In 2002, Norma Jean Ryan became Brownsville’s first and only (to this day) female mayor.

After her years as mayor, she again worked with BARC, giving tours in the historic St. Peter’s Church. It was the church of her childhood and where, as a devout Catholic, she attended mass as an adult. Her nephew Keith Ryan said, “She was a tour guide in our church. She studied the stained-glass history and the Irish coal-mine towns. ‘Patch town’ history was a big interest of hers. Any research she could do for the old history of the town she would try to preserve.”

Norma’s nephew Timmy Ryan shared: “Nobody’s ever been more positive than her. One of her sayings was, if you can’t say anything nice, don’t say anything at all. She lived by that, and her faith in God and her family and friends and keeping everybody together in a positive manner.”

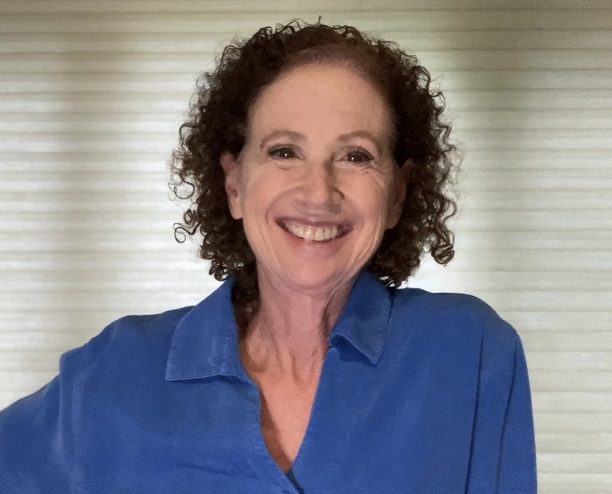

Norma Ryan taking pleasure in serving her food to others. Photo courtesy of Augie Carlino.

Her house was the place to gather, and the place to eat. Along with restoring Brownsville, cooking was one of her great passions. “She baked every day. Her life was in the kitchen. You never left her house hungry. She always had cinnamon rolls, pies, cookies, chicken, homemade pasta. If she wasn’t cutting hair, she was cooking,” Barantovich said.

Carlino said, “The last time I saw her, I was taking a group of people from Carnegie Mellon University through a tour of the Valley, and one of the stops was Brownsville. We were touring the Flatiron Building, and she showed up with all these cookies—I mean, a big, big tray of cookies! Then she came over to me and gave me a big hug and said, ‘I’m sorry it’s only cookies.’ And I said, ‘What are you talking about?’ And she said, ‘I wanted to make a gnocchi or polenta for you, but I didn’t have the time nor the energy to do it.’ She was really, really regretful about that. There’s not enough words in my vocabulary to describe her. She was just an amazing person.”

When Carlino went to Brownsville for his first lunch with Norma, he returned to his coworkers complaining. In the staff meeting, they lamented that in all the years of working in Brownsville, Norma never invited them to lunch.

“I come in,” Carlino said, “and I’m on the job literally a month or two, and not only do I get invited down there by her, but she’s serving me polenta. Polenta! Homemade sausage. Homemade bread. And I realized my coworkers were joking with me . . . I’m so thankful that she shared a number of years in my life with me. We just had a great time together!”

During the past year, in her role as Coordinator of Rivers of Steel’s Creative Leadership Program, Ashley Kyber had weekly—sometimes daily—conversations with Norma. She spoke fondly of her: “Benevolent in her love of Brownsville, Norma Ryan was a wealth of cultural history and a visionary optimist for the future of her community.”

Norma embraced a joie de vivre. Even with her boundless energy and countless hours of research, Barantovich said, “She always made the time. Her saying was, ’Stop and smell the roses’ and enjoy life. That was how she answered her phone on her message—it’s still on there. If she didn’t answer the phone, she would say, ‘I’ll call you back, and take time to smell the roses.’ She was a good people person. Great smile. She was a lot like a rose—beautiful, but she could be prickly if she wasn’t getting her way. She was bound and determined to see the way she wanted to get things done.”

Keith said, “One funny story: She was always looking for volunteers for any work everywhere. She finally got a volunteer one time to do some job like pulling weeds or pulling up poison ivy—things like that, and she called me wanting me to give him some advice on how to go a little bit faster. And I said, ‘Aunt Norma, he’s a volunteer! He’s working for nothing! If it takes him all week or all month, what’s the hurry?’ She figured that if he was going to volunteer, he should be up to her speed. We talked her out of that.”

There was Norma time, and there was everyone else’s time. But even Norma slowed down. Eventually, she spent winters in Florida, from late fall to late spring; however, no distance could keep her from calling to make sure things got done in Brownsville. Her heart, her smile, her determination—and perhaps a wafting aroma of homemade sauce—continue to weave their way through the town Norma loved so much.

“Brownsville has lost its greatest spokesperson,” said Dick Wallace, Rivers of Steel’s Board Chair.

Born in a time when Brownsville was the place to be, Norma passed away on April 30, 2024. Brownsville has reclaimed much of its former glory because of Norma and the people she brought together. Her life was celebrated on Saturday, June 1, at her beloved St. Peter’s Church by the people she loved and who loved her.

Read more about Norma Ryan in this article from the Observer-Reporter.

Julie Silverman is a museum educator, tour facilitator, and storyteller of astronomy and history for various Pittsburgh area organizations, including Rivers of Steel. A Chatham University 2020 MFA graduate, her writing is most often found under the by-line of JL Silverman. Occasionally, under the name of Julia, she has been seen on TV.