The Golden Age of Carrie Baseball

Barney Terrell traces the origins of Carrie Furnaces’ baseballs teams from the earliest mention in 1895 through their final season in 1923 in this article about the players and the recreational culture that supported them.

The Carrie Nine & the Industrial Baseball Leagues

In the 1890s and the first decade of the 1900s, baseball was everywhere in the United States. Between 1876 and 1901, no fewer than six major leagues fielded teams. “Fast” minor leagues with high-quality teams proliferated to feed the increasing hunger for recreation and competition. Every town had its own ball club, and many business owners sponsored teams of amateur players. Industrial leagues were common in the Monongahela River Valley, serving not only as a source of pride for the mills, but also as a source of recreation and release in a time of brutal working conditions.

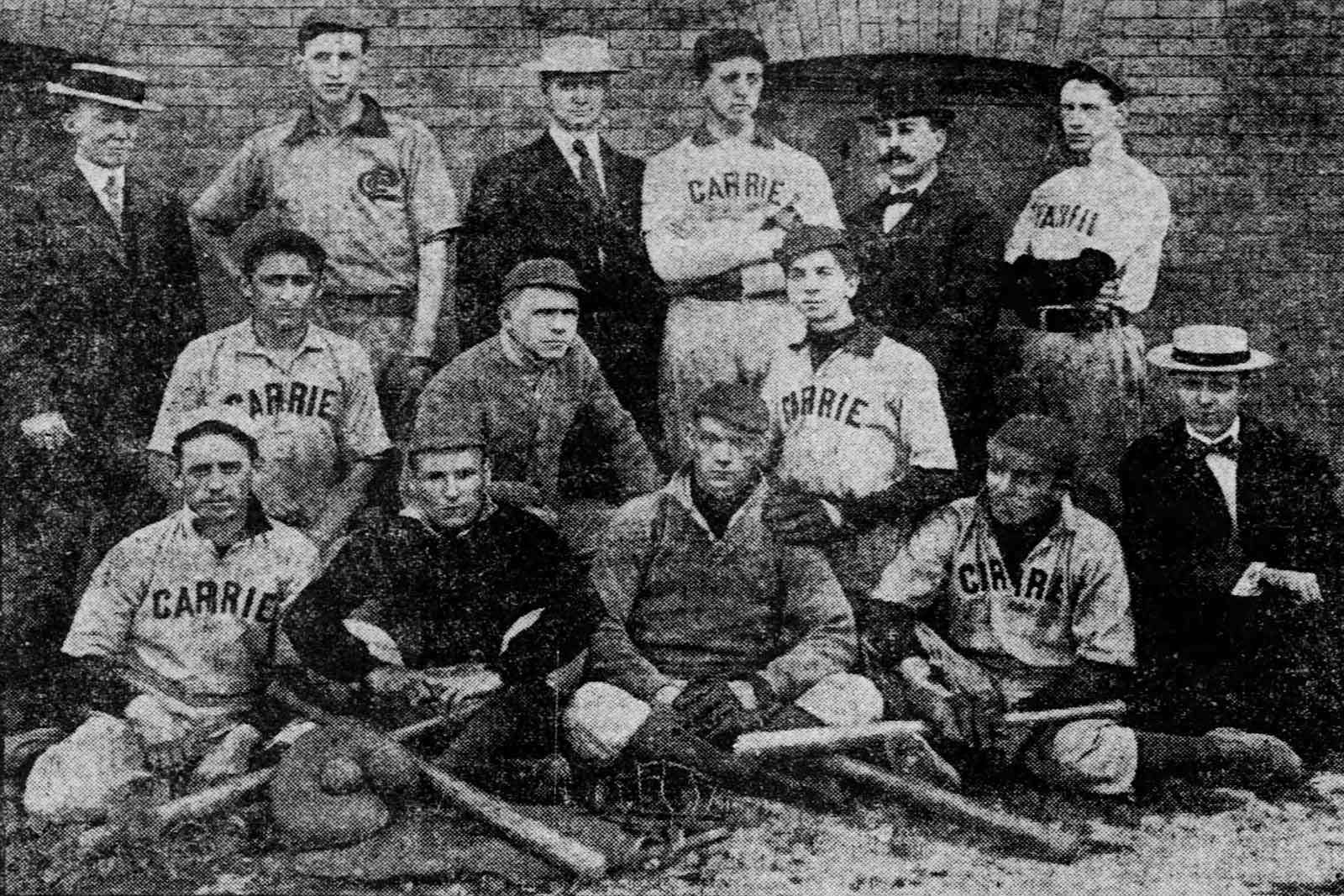

The Carrie Furnaces were no exception. June 22, 1895, saw the first mention of a Carrie Furnace ball club in local newspapers in a 17 – 14 defeat at the hands of the Consolidated Steel and Wire team. This Carrie Nine—a name referencing the number of players in the starting lineup—was likely brought together for weekend games to play against nearby mills in Braddock and amateur nines from Rankin and Swissvale.

The Pittsburgh Press, June 24, 1895 pg. 9

Between 1895 and 1907, the Carrie Furnaces likely had a team every summer. These teams scheduled games themselves and sometimes passed a hat through the crowd to take up a collection for the players. While not a part of established leagues, these teams served to promote athleticism, public goodwill, and comradery among industries, their employees, and rapidly expanding cities. Baseball was a sport where an individual could excel, but the outcome of a game was usually decided by the efforts of the team. Even the most uneducated, poorest, or least experienced players could make their mark by superior play. The Homestead Steel Works operated its own baseball league, occasionally supporting a dozen teams, each from a different part of the mill.

The Carrie Furnace Baseball Club & the Twilight League

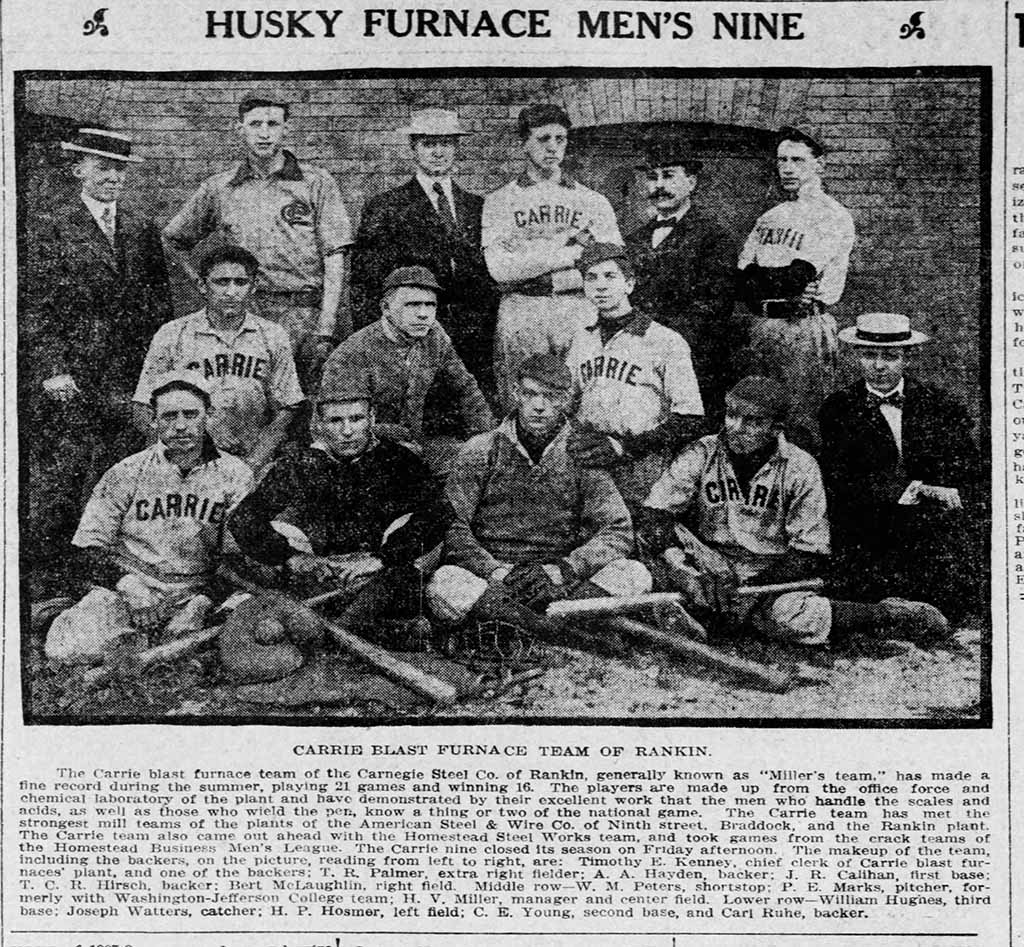

In 1908, the Carrie Furnace club burst back onto the amateur scene in Pittsburgh, posting a 16 – 5 record between May and October. The team was dubbed The Millers in honor of their starting center fielder, H.V. Miller, who was a member of the chemical division at Carrie and performed testing on metal samples and gas. As the caption of the following picture points out, most of the club was drawn from the offices and chemical division at Carrie. The club played on Friday and Saturday afternoons, generally tracing the schedule of the Homestead Business Men’s League. This league was a “twilight” league for several years, fielding teams of grocers, plumbers, city employees, and office workers from the Homestead Works. Games were played at 5:30 p.m., meaning that all of the players were professionals during regular business hours. The majority of the workers at Carrie or Homestead worked six-day weeks of 72 hours or more and could perhaps catch a few innings of the games after their shift ended. Club backers, such as chief clerk Thomas Kenney, supplied uniforms and equipment and split scheduling duties with Theodore Hirsch, the assistant superintendent at Carrie. Hirsch’s son, Theodore Jr., was a student at Pitt as well as an apprentice in the electrical department at the Homestead Works.

The Millers were led on the field by two players: their namesake, Miller, and Fred Hosmer. Miller was a strong-hitting and superb center fielder. Fred Hosmer split his time between the outfield and third base. In three games for which box scores exist, Hosmer handled 15 chances at third base without an error—an exceptional defensive performance!

Gloves were common in baseball for over a decade by 1908, but most games were played on poorly kept fields and often extended into near darkness. Those factors, combined with the discoloration of the single ball used throughout the game, reflect the challenges in the game that one might not consider as factors today.

The Pittsburgh Press, October 11, 1908 page 22

At least two in Carrie’s club played college-level baseball before working at the iron mill and were the strength of the club. Hosmer played while studying chemistry in Maine. In the above photo, Philip Marks is mentioned as “formerly with Washington-Jefferson College team.” To be a truly competitive team in this time period, the most important positions were the pitcher and catcher. A pitcher who could throw quality curve balls and off-speed pitches (variously called in/out shoots and drops) gave a team a leg up. If one of those pitchers was on the team, however, you needed a catcher who could handle the speed and movement of the pitches. With Hosmer and Marks, Carrie had both. In Joseph Watters, they even had an extra catcher as good as Hosmer.

The next season, however, Marks left to take a job at National Tube in McKeesport, where he managed a team in the West Penn Amateur League. Watters also did not play for Carrie the next year, and the Carrie team disbanded in late August after having difficulty scheduling games.

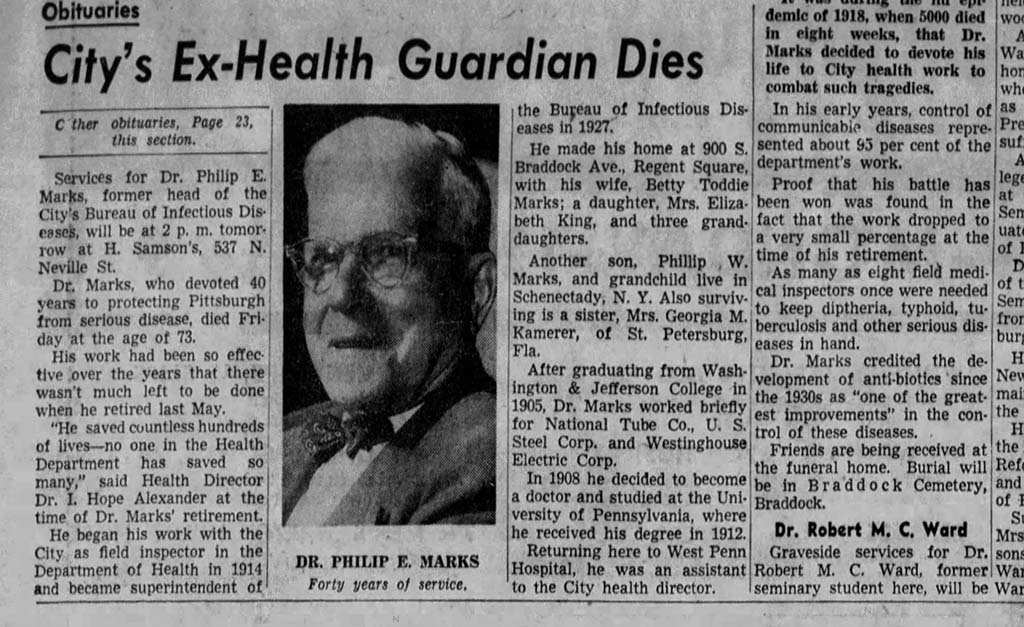

The career of Philip Marks did not end at National Tube, however. He decided to go into medicine and spent nearly 30 years as the director of Pittsburgh’s Bureau of Infectious Diseases.

Pittsburgh Press, Feb 20, 1955 Page 10

A Return to the Amateur Scene with the Tri-Borough League

Carrie team baseball returned for a third time to the amateur scene in 1919. That year, teams from Braddock, Rankin, and Homestead formed the Tri-borough League. “Tri-borough” was a commonly used name for any amateur league in the Pittsburgh district—and the 1919 edition was at least the fourth since 1900. Pittsburgh, like much of the United States, saw an explosion of amateur and semipro teams in the years following World War I. By 1925, according to Rob Ruck in Sandlot Seasons, Pittsburgh featured more than 200 semipro and amateur teams in dozens of leagues.

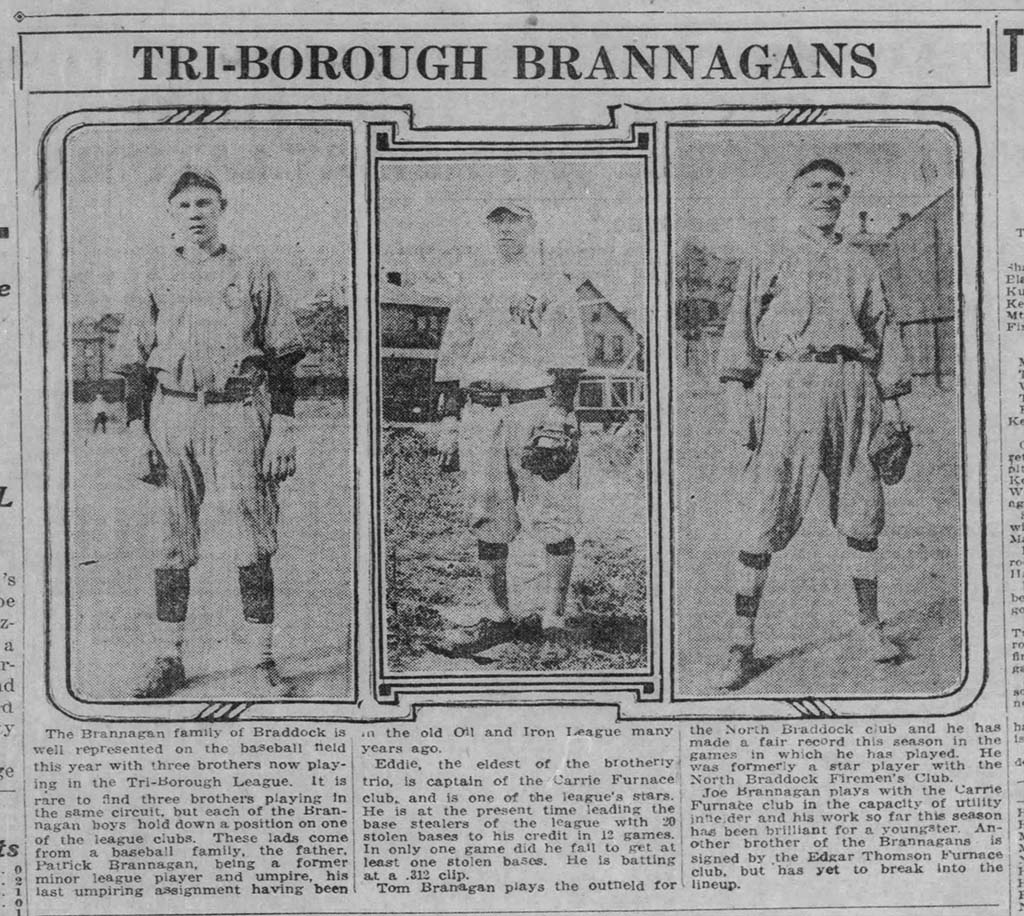

The 1919 team was one of the strongest teams in the Tri-borough League. Ross Calihan, a chemist, played for both the 1908 Carrie team and the 1919 edition. He was about 35 years old in 1919 and appeared in only five games. The leader on the field for the team was Eddie Brannagan. Eddie and his brother Joe played for Carrie, while one of their other brothers, Tom, played for North Braddock. Eddie was a fast runner and good fielder, and led the Tri-borough League in stolen bases in 1919.

Pittsburgh Daily Post, July 27, 1919 page 21.

The Brannagans also performed in musicals and plays at the Carnegie Theatre in Braddock, while Joe was also a member of the Braddock Men’s Chorus. Their father played baseball in the 1880s and served as an umpire in the Oil and Iron League, where he likely saw the rise of Hall-of-Famer Rube Waddell. (George Edward “Rube” Waddell was from Butler County and played for several teams, including the Homestead Athletic Club and the Pittsburgh Pirates, in a peripatetic career. While an outstanding pitcher for six years for the Philadelphia A’s and St. Louis Browns, he is better known for chasing fire engines and appearing in vaudeville acts, according to legendary tales shared by his manager, Connie Mack.)

Besides Eddie Brannagan, Ernest Morgan was the best hitter on the team and is recorded as one of the fastest men in the league. Levi “Larry” Kilbury was called the team’s “Iron Man” by The Pittsburgh Press. On days that he was not pitching, Larry played catcher and corner outfield. Jess Cook, a machinist at Carrie, was the other main pitcher for the team. Their manager was Jim Lose, a mechanical engineer at the Furnaces who was originally from Kansas. Lose worked at Carrie for nearly 15 years and later served as executive vice president at U.S. Steel before his retirement in 1956. Larry Kilbury and Braddock’s Jess Scott were talented enough pitchers to get invitations to try out for minor league teams in Western Pennsylvania.

The Carrie Furnace club finished third in the Tri-borough League in 1919 and was invited back to play in 1920. However, Carrie lost its best pitcher in Jess Cook In their first game, Eddie Brannagan took the mound against McClintic Marshall and was torched for 11 runs. (McClintic Marshall was a large independent steel company involved in the construction of the Gulf Tower in Pittsburgh and the Panama Canal locks, among other projects. Located on land adjacent to the Carrie Furnaces, it was founded in 1900 by H.H. McClintic and Charles D. Marshall with funding from Andrew Mellon.)

The 1920 Tri-borough season was short for the Carrie Furnace club. On June 18, 1920, the league cut four teams to improve the quality of play; Carrie Furnace, St. Josephs, the Swissvale Windsors, and the Korch Crescents were dropped from the league. Between them, the teams had a record of 4 wins and 15 losses. The Carrie Furnace club lost its first five games. Only one of their players, Eddie Brannigan, was snapped up by another club—the same McClintic Marshall team that hit him hard in the opening game of the season. During the next five years, the Carrie Furnace team still played games against amateur clubs on the weekends but never got back into an established amateur league. Larry Kilbury was the captain of the club in 1922 and 1923 and scheduled games for the team.

The population of Pittsburgh more than doubled between 1890 and 1920 to 588,000. Baseball was, for immigrant workers in the mills and rural migrants coming into the cities, a common touch point—an introduction of the “American Pastime” and industrialized society. The Carrie Furnace teams between 1895 and 1925 featured immigrants, men from Pittsburgh: doctors, scientists, machinists, and railway engineers. While the “golden age” of Carrie Baseball was short, it is a great reminder that each individual who worked on the site has a story all their own.

Barney Terrell is a tour guide, historian, and researcher for Rivers of Steel and is a tour facilitator at The Frick Pittsburgh. He is a member of the Society for American Baseball Research, a true crime author, and a trivia host.

Barney Terrell is a tour guide, historian, and researcher for Rivers of Steel and is a tour facilitator at The Frick Pittsburgh. He is a member of the Society for American Baseball Research, a true crime author, and a trivia host.