By Angela Biederman, Chief Deckhand | Featured Image: Angela Biederman birdwatching on the Explorer riverboat.

“Birding from Explorer” is an ongoing series of articles by Angela Biederman, Chief Deckhand on the Explorer riverboat. A relatively new birder, Angela shares her observations of migrating birds, as sighted from the boat’s home dock on Pittsburgh’s North Shore, near the headwaters of the Ohio River.

A Tale of Two Ducks: Canvasbacks and Redheads

A Tale of Two Ducks: Canvasbacks and Redheads

The month of February brought so many migratory birds through and to Pittsburgh’s three rivers that, short of offering an extensive calendrical list of sightings, I might hardly know where to begin. I even considered opening this installment with the simple introduction: Brace Yourselves. Rather than opt for a chronological retelling that might quickly disinterest readers, I decided to focus on two diving ducks that are in the same genus and are a similar-looking species: Redhead (Aythya americana) and Canvasback (Aythya valisineria) ducks. Reasonably sized flocks of these ducks migrated through within a week of one another, and stayed for about three weeks. Prior to their arrival, I had not seen either species before in my life. Part of the reason I wanted to narrow down this article to two diving ducks was because my very first sighting of the Redheads made me initially think—before looking in any field guide—that they were possibly Canvasbacks. I had seen Canvasbacks in Captain Ryan O’Rourke’s Birds of the Three Rivers onboard, but Redheads are not in that compilation (side note: I’m happy to say there have been several diving duck species spotted this winter that will have to be added to that book!). It wasn’t until I opened Peterson’s field guide to Birds of Eastern and Central North America and saw a duck very similar to Canvasbacks that helped confirm what had just flown in.

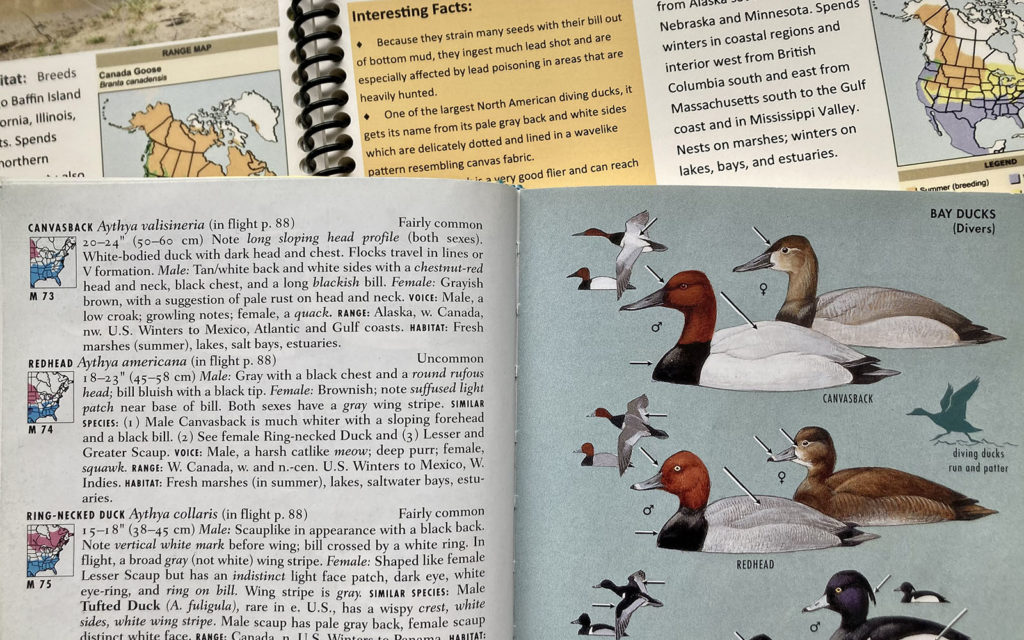

Canvasbacks and Redheads in Peterson’s field guide

Once I saw Canvasbacks and Redheads side-by-side in the field guide, I was quickly able to see the difference between the Canvasbacks I thought I saw, and the Redheads I knew I was looking at. This process of comparing similar species might be helpful for anyone new to birding, who wants to get started, or is curious about things to make note of to help you distinguish between similar kinds. After the arrival of the Canvasbacks, I did some additional research on both species’ behavior and history, like the overhunting of Canvasbacks that decimated their populations, which was inspired by conversations and articles that carried a lot of overlap and piqued my curiosity to find out more. Hopefully some things I learned about the four migratory flyways spanning North America, and related issues like hunting regulations and conservation efforts, can be revisited more in depth down the road.

I first saw a total of 27 Redheads (17 male, ten female) in the late morning of February 8th, off the starboard side of Explorer, making their way towards the stern to eventually settle near our floating dock. I can’t recall what I was even doing when along came this raft of ducks I had never seen before. (Another side note: a group of ducks has many collective nouns, including “raft”, “paddling”, “brace”, “flush” and “team”. I’m sure there are more, but I plan on randomly testing out these terms and we’ll see what sticks.) The Redheads came in and got close enough for me to take some good photos, and get a good look to help me to identify them. I watched them for a while as they almost immediately started foraging for food; they were quite lively and fun to watch, until most of them calmed down, and tucked their bills in their back to snooze.

Male Redhead Ducks

Female Redheads

Before I had ever even seen any Canvasbacks, I could tell from the images in the field guide that the birds behind the boat were Redheads. One major indication was the males’ backs and sides were not predominately white like they typically are on male Canvasbacks (which gets its common name specifically from the males’ canvas-colored back). Redheads have a much grayer back and sides; as well as a rounder, more rufous, and lighter cinnamon-red head. A Canvasback’s dark, chestnut-red head is more sloped, and their bill is longer and black. Another feature of Redheads that’s very distinguishing is not just the shape of their shorter bill, but also its color: it’s bluish gray, with a whitish ring preceding a black tip. The black and gray tails of Canvasbacks and Redheads are similar, as is their all-black chest; but another distinguishing trait is their eyes: the male Redheads I saw had yellow eyes, and while the eyes of both sexes of Canvasbacks are yellow for the first 10 to 12 weeks, they soon become a piercing bright red for the males, and a dark brown to black for the females.

While most of these indicators apply to the males (also known as drakes), a couple apply to the females, or hens: namely, the head and bill shape and bill coloration, which was the best way I was able to distinguish the female Redheads from female Canvasbacks. Canvasback hens have plumage more akin to their male counterpart, with a lighter back and sides, a slightly darker chest, and a suggestion of pale rust on their head and neck. The Redhead hens are overall brownish, with a suffused light patch near the base of their bill.

On February 11th, three days after I first saw the Redheads, the Canvasbacks arrived. In fact, this day was like hitting the migratory-diving-duck or bird-spotting jackpot. It was the afternoon, I was in the pilot house of Explorer, and noticed a bunch of spots on the water relatively close to shore in front of the Carnegie Science Center submarine. This area of the river is right in front of the boat launch under Heinz Stadium, where I see Double-crested Cormorants, Ring-billed Gulls, Mallard Ducks, and Canada Geese almost every morning on my way to work. It is also where I have gone birding to get a glimpse of some other recent migratory ducks, like Ruddy Ducks or ol’ miss Melani p (what I affectionately started calling the female Surf Scoter that was here for a couple of weeks in November). I couldn’t identify the ducks at all from the boat, but could tell that some of the spots were very white (Canvasbacks? I wondered), and others were quite dark. I walked a newly purchased field scope to the boat launch to get a better view, and identified the following ducks, all of them divers: Redheads, Buffleheads, Common Mergansers, roughly ten to 15 Canvasbacks (that were definitely Canvasbacks, and more came in over the weeks), Ruddy Ducks, and Greater and Lesser Scaups – the latter two being other species in the Aythya genus and ones I had not previously seen. In awe, I watched these seven species of male and female diving ducks (there were only two female Ruddy Ducks – I still have not seen a male) in this congested little area for well over an hour. I took many photos and videos, two of which can be viewed on Explorer’s Facebook page, and here are a select few:

Redhead and Canvasback drakes

I have since learned that this combination of so many different diving ducks is actually quite common for some wintering waterfowl. In the non-breeding season, Redheads, Canvasbacks, and scaups (which, again, are in the same genus) often flock together, occasionally along with wigeons and American Coots. Incredibly, their numbers can climb into the tens of thousands. One of the most interesting things I read on All About Birds is that Redheads are so “exceptionally gregarious” they will sometimes alight at hunting decoys before hunters have even finished setting them up.

Within a day or two of witnessing this highly social flush of ducks in all of their speciated variety, I was catching up with my father on the phone and telling him about it. My father—a life-long outdoorsman, and man who has gained more wisdom from decades of hunting, fishing, farming, and gardening than from what a formal education could afford—told me that at one point Canvasbacks’ population numbers were so low due to overhunting that restrictions were established so they didn’t become extinct. Canvasbacks use their bill to strain seeds from mud; they ingest a lot of lead shot and are especially affected by lead poisoning in areas that are heavily hunted (fortunately this threat has somewhat diminished since lead shot used for waterfowl hunting was federally banned in 1991). Curious to find out more about the health of their populations now, and to what degree they were overhunted, I did some digging that led to some very interesting finds.

Canvasbacks get their scientific name, Aythya valisineria, from Vallisneria americana, or wild celery, which is Submersed Aquatic Vegetation (SAV) that happens to be extremely sensitive to climate- and pollution-related changes in water quality. Canvasbacks’ habitat locations have shifted in part due to the loss of this SAV in areas where it once flourished (such as the Chesapeake Bay—a bottleneck on the Atlantic Flyway), but much of their habitat degradation occurred well after the overhunting that happened in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Here is the relationship: the wild celery diet of Canvasbacks resulted in their meat being believed to be the tastiest of any duck, which made them the favorite targets of commercial market hunters that supplied large cities of the North with fresh meat. The most sophisticated consumers sought to dine on this luxurious duck meat, and a pair of Canvasbacks would have cost more than one hundred of today’s dollars—clearly a dinner for the rich and well-off. Mark Twain even described Canvasback as one of the “quintessential American foods” he missed while traveling Europe. Demand for this duck meat drove commercial market hunters to bring their populations to extremely low levels, and these endeavors were aided by the industrialization of market hunting and America: after 1865, shotguns, railroads and refrigeration made killing and transporting large quantities of Canvasback meat viable. I also read about punt guns, sink boxes, and handmade or hand-carved decoys made by the Chesapeake Bay hunters—and even Native Americans 2,000 years ago—that all assisted in attracting and capturing this prized wild game.

After decades of overhunting, and recognizing birds travel across state lines (and countries and continents), the Weeks-Mclean Act of 1913 was implemented to transfer the regulation of waterfowl management from states to federal governments to help protect and revive Canvasback populations. Without enforcement, however, these regulations has little impact; this led to the Migratory Bird Treaty Act in 1918, which outlawed commercial market hunting and provided funding for enforcement. Recreational hunters became a significant interest group, and provided support for waterfowl conservation, along with other programs such as the Migratory Bird Hunting & Conservation Stamp (commonly called the Duck Stamp). I also read that other organizations such as the National Wildlife Refuge System and Ducks Unlimited, as well as Federal Farm Bill programs, have all aided in wetland conservation, and thereby the revitalization of Canvasback populations. Canvasback populations are still largely affected by breeding ground conditions, particularly wetlands such as marshes and the fascinating Prairie Pothole Region of Canada and the northern Midwest. When these wetlands are unavailable due to drought or other environmental factors, Canvasback hens will delay or skip nesting altogether, which is why populations had again declined during the 1930s drought that caused the Dust Bowl. Canvasback populations fluctuated through the 20th century, and dipped very low again in the ‘80s. Fortunately today, numbers have rebound, their population is stable, and about 700,000 ducks were reported in 2017, with a slightly lower estimate for 2020.

After learning all this, I felt grateful to have seen Canvasbacks passing through here. While I thought they had all left over the weekend before the river started flooding on Sunday, I took a little jaunt downriver on the trail this week and saw maybe half a dozen floating around Peggy’s Harbor. It’s been at least a week since I’ve seen any Redheads, but their reputation isn’t sitting well with me: I learned the hens are major brood parasites, which means they lay their eggs in all kinds of other ducks’ nest (such as Canvasbacks’) which negatively impacts the original ducks’ hatching numbers. Regardless, I hope to see both species come through again, along with all the others I’ve seen this month, which I look forward to sharing more about in posts to come.

Until then, here is the most recent video I took of Canvasbacks (with a pair of Lesser Scaups, and an uncommon female White-winged Scoter), filmed Friday of last week right before I was about to leave the boat. I was stepping onto the gangway, saw them off the stern, and decided to unlock the door, head back in, and grab some binoculars to watch them for a while. The river was extremely calm, the afternoon was quiet, and it was a rare moment I took to just sit and observe. Most of the time, I am busy with other things, and just get sidetracked (sometimes for a while) by a sighting. It was a moment I loved, and hope it encourages you to head to one of our riverbanks, look for what’s happening on the water, and see what you can identify.

Canvasbacks off Explorer’s stern

Author’s Note: A correction was made on March 10, 2021. Thanks to one of our readers, I was informed that my previous statement referencing “the lead shot ban” was somewhat misleading: lead shot is not federally banned for all hunting and fishing purposes. In 1991, lead shot for the use of hunting waterfowl was federally banned, but not for all hunting ammunition and fishing tackle. Some states, like California, have banned the use of lead in any ammunition, largely because lead poisoning from ammo is one of the biggest reasons California condors remain on the endangered species list. Other states have taken similar initiatives. On the last day of the Obama administration, a federal ban was issued for hunting with lead ammunition in national parks and wildlife refuges, but former Interior Secretary Ryan Zinke of the Trump administration lifted this ban promptly in March 2017.

A new lead ban was introduced to the House of Representatives on January 21, 2021.

Here are the most current shot regulations for hunting waterfowl and coots in the U.S.

If you have any comments or questions on this or future articles, please do not hesitate to reach out! I am still very new to birding, and am bound to make some mistakes; but I truly welcome any corrections or feedback! Please email me directly at abiederman@riversofsteel.com, or send us a message on the Explorer Facebook page. Thanks for reading!

Angela Biederman began working for Rivers of Steel as a part-time deckhand in March 2018. About a year later, she became the full-time Chief Deckhand, and is responsible for maintaining Explorer year-

This photo essay is the third in a series of articles by Angela highlighting her sightings of migratory birds. All the images of the birds were photographed by her, usually through a set of binoculars with her phone. Your can read her prior post from February here and her first post from December, 2020 here.

A Tale of Two Ducks: Canvasbacks and Redheads

A Tale of Two Ducks: Canvasbacks and Redheads