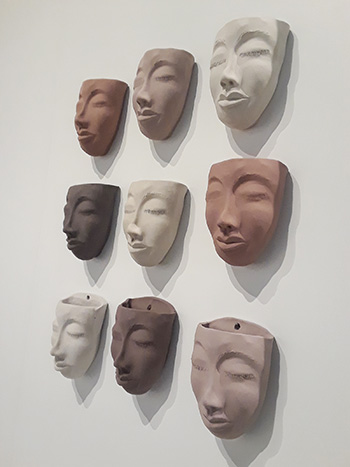

Functional ceramics by Mary Martin, a member of the Women of Visions artists collaborative.

Heritage Highlights

Rivers of Steel’s Heritage Arts program strives to represent the region’s diverse cultural heritage, from ethnic customs and occupational traditions directly linked to Pittsburgh’s industrial past to new American folk arts and cultural practices emerging from the region’s diverse urban experience. Usually passed down from person to person within close-knit communities, these cultural traditions are as varied as they are unique, each representing one aspect of what makes southwestern Pennsylvania’s heritage so rich.

In this month’s installment, Rivers of Steel’s Heritage Arts Coordinator Jon Engel met with Women of Visions, a local Black women’s art collective. The group, which is based in Pittsburgh, seeks to help Black women show their art through collaborative exhibitions and other programming. Many kinds of artists are represented in the collective, including heritage artists practicing traditional African-American arts. This year, Women of Visions celebrates their 40th anniversary, and four of their members spoke to Jon about their individual crafts and the way the organization has helped them as artists.

Women of Visions

An Interview by Jonathan Engel

Through their conversations with Jon, artists Christine Bethea, LaVerne Kemp, Mary Martin, and Janet Watkins share elements of their craft and reflect on the how the Women of Visions organization has shaped their careers while providing support, camaraderie, and inspiration to themselves and other members.

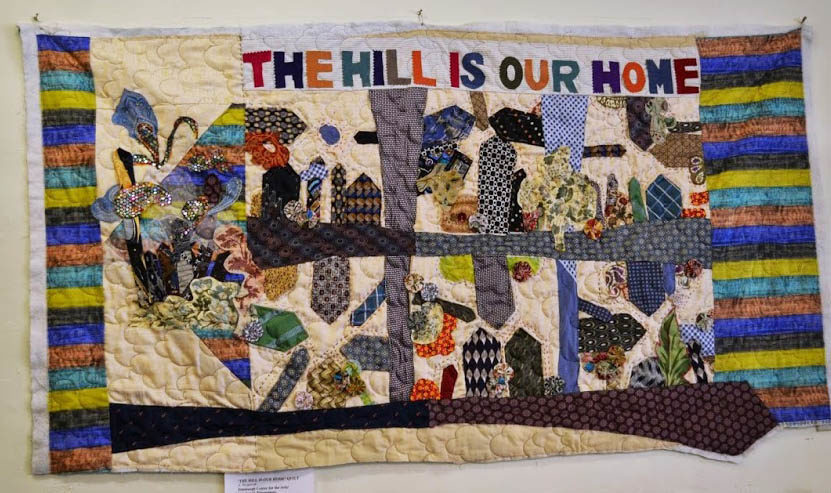

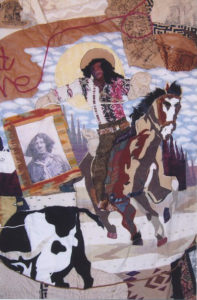

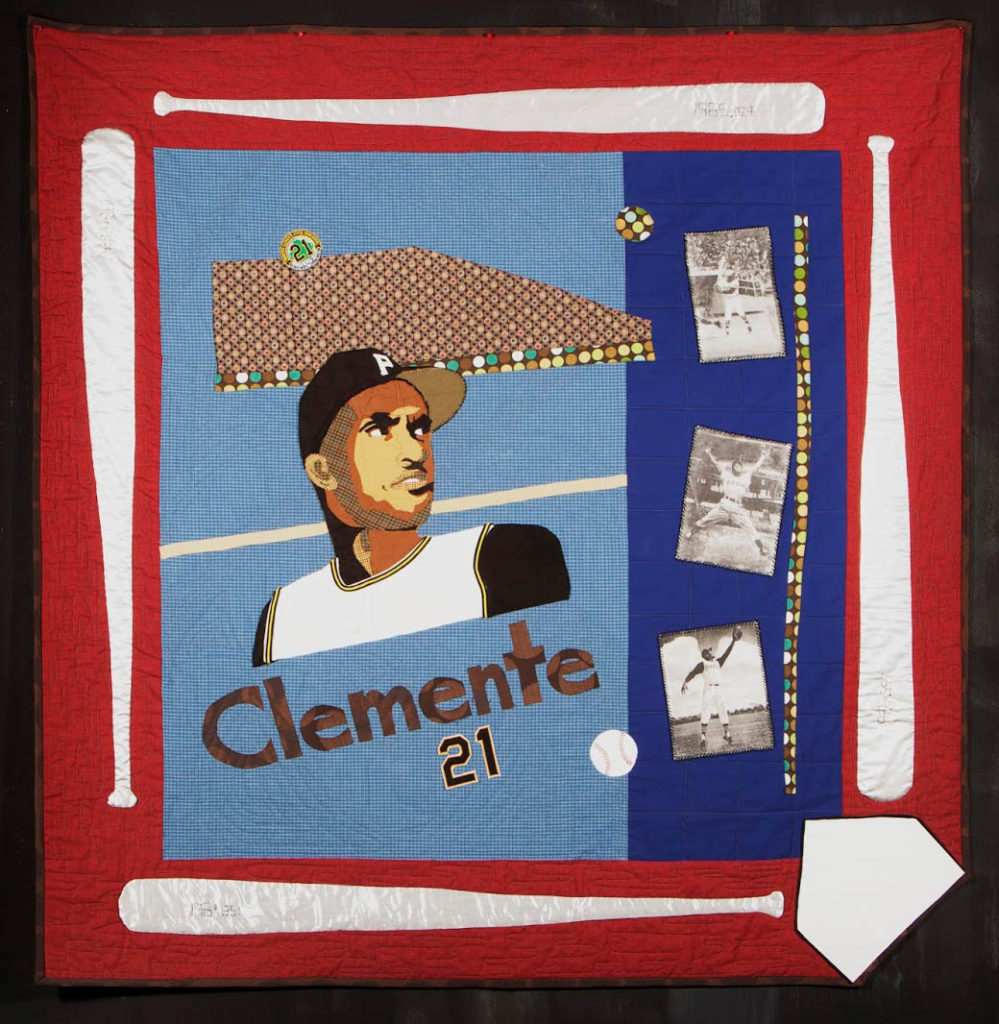

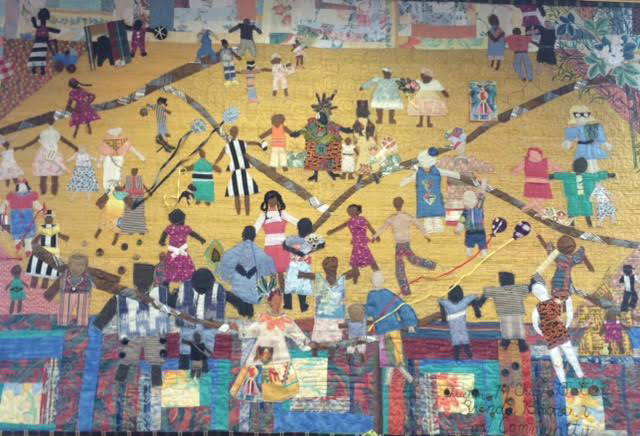

Christine Bethea—A tradition of Quilting

As an art quilter, folk quilter / storyteller, and traditional quilter, I do nearly all the genres associated with the art form. The majority of my work, I machine quilt. I did a lot of it by hand at one time but found that time, for me, was best spent in the design. One thing I do prefer from the traditional school is the use of fabrics taken from vintage clothing. In the past, that’s where women got their fabrics. They almost never bought their cloth new. Most of these fabrics are no longer manufactured, and so any quilt I make will be quite unique because of the blend of old and new.

“The Hill is Our Home” by Christine Bethea.

One of Bethea’s favorite pieces, “Deadwood Dick/African-American Cowboy”. She says she especially enjoyed “researching the history of black cowboys, who I was told as a child never existed”.

Why do you quilt? How does it fit into your life?

I believe I was born to it. My grandmother quilted, and her mother before her. It was a kind of therapy for me, and most likely them too. You could forget all your cares concentrating on a quilt. It made my children crazy watching me quilt. I did it a lot during my divorce. My daughter even wrote a poem for school, which I will never forget: “My mother made a quilt. She built and she built and she built. She built a big square layer by layer.” I think my friends thought it was pretty old fashioned. I found my “tribe” when I took a class at Pittsburgh Center for the Arts with Louise Silk, and later joined an African American quilt guild.

I’ve learned that I’m a salvage girl. I’m a Dumper Diver and love all that is recycled and repurposed in the world. I do assemblage art as well. Nearly all the quilters I know are doing some other kind of fiber art or mixed media art.

Who taught you to quilt?

I used to sleep under my grandmother’s quilts as she made them, because she worked on them in her bedroom after dinner. We grandkids often squeezed in with her. She’d be sitting on her favorite chair beside her bed, quilting, and I’d have about half the quilt—the done part—over me. When I woke up in the morning, the quilt would be mostly finished, and I’d be completely covered. She had worked on it long into the night, and often when my eyes popped open, she was already in the kitchen cooking breakfast. Those days were magical, filled with stories about her mother, gardening, and watching her take a short break in her constant work to skin a whole apple without breaking the peel. I’d wait in anticipation, but she never failed to produce a perfect spiral. Afterwards, she’d always share a slice or two of apple with me. It was the perfect bedtime snack.

What does quilting mean to you and your community?

“Roberto Clemente” by Christine Bethea.

As with my grandmother, quilts have been made by African American women—indeed, women the world over—not only as a necessity to keep their families warm, but as a creative release. It was an art form that was totally their own. Something that was not controlled by a world who saw little value in them or their work. When you worked on a quilt, you knew it was all yours. Made by cloth you chose and wrought through hours by your own hands. Even today, women who are unable to sell their quilts say: “It would be like giving away one of my children.”

How has quilting changed over time?

Not too much. Thank God. Much of the same block styles, the choice in traditional fabrics (like muslin), and the construction of quilts is very much the same. There are new construction techniques, however. The long-arm sewing machine, which I thought was invented maybe 30 year ago, was first made in 1871. Of course, the new ones are faster, and the movement has been vastly improved, but sewing is sewing. You can only make it easier and faster. I think that’s the secret of its staying power. Once you pick up a needle and sew, you connect with women—and men—going back to the ice age.

“Hey-Day on the Hill” by Christine Bethea.

How do you think quilting will change over future generations?

Actually, I don’t see it changing. This is one tactile artform that no one is in a hurry to modernize, not so much. Doing what was always done is part of the charm of quilting. It’s not hurting anything, its eco-friendly, and it makes people happy.

What does Women of Visions mean to you? What do you want for the group?

At a time when the art world made it clear you were not part of its artistic conversation, you had to go somewhere. For many women in Pittsburgh, that was Women of Visions. I wasn’t a member at the beginning, but I was there for 16 years of my life. They let me know I was an artist, and it was alright, and they didn’t really care what other people thought about it. We wanted to create. We needed to create.

If we do our job right as an organization, WOV should be looking ahead to get recognition nationally. We’ve been swimming in the same pool for a long time, which is one reason I became President. We were getting stuck. We needed to pass the reigns to the next generation of young women and African-American artists.

I hope [people] will say of my work: she was at the forefront of Pittsburgh women working with salvage, as an African-American quilter, and as a mixed media artist.

LaVerne Kemp—A Culture of Weaving

LaVerne Kemp

My medium at any time might be weaving, quilting, felt making, crocheting, basket making, book making, spinning, or dying, but my main focus and education has been in weaving. My art is soft and tactile. It almost always relates back to my African American heritage and traditions by the colors, patterns, and symbolism in my work. For example, if I am weaving, I have to put my own spin on it, and you can always feel my culture shining through.

What kind of weaving do you do?

I make a variety of items because I participate in art shows, not as much as I used to, but I like to keep my options open. My artwork ranges from large scale wall hangings and trees to smaller home decorative pieces like table runners and area rugs to shawls, ponchos, and jackets. I use a variety of materials from wool and silk that I purchase from across the US to repurposed fabrics, yarns, beads, and buttons for embellishments. I might turn anything into a piece of art! I don’t like to waste and I’ve always been able to see the beauty in things that others don’t, even people!

How did you learn to weave?

A coat by LaVerne Kemp, stitched from upcycled materials.

I have been weaving since I took an elective in college called Threads and Fibers, where we made baskets, macrame, rugs, etc. And it changed my life. I produced large wall pieces like my professor, Leslie Parkinson, and she talked me into taking a weaving class. Although the loom was intimidating, I progressed from weaving a sampler to a coat in no time. I never had an art class before college but I always knew that I had an artist’s spirit. I always felt a little different but very creative, like both of my grandmothers. I come from a family of people who all had their own businesses so the art helped me assume my place in the world. I know that I was meant to be an artist/entrepreneur. This was God’s gift to me, and I was determined to make it happen, and it has. My art is my passion! I have to “touch” it daily or it feels like something is missing.

How has weaving changed over time?

Weaving has been around as far back as Biblical times. It is how people made their fabric for clothing and everyday items such as tent covers and table coverings. My personal interest is in the African traditional cloth, with their colors and patterns and textures and the meaning behind the symbolism, and how they were and still are made. It used to be that the men did the weaving in certain cultures while the women took care of the daily chores and the children. I believe that has changed somewhat now. Different parts of the continent have various traditions and there are now more women weaving, as well as different types of looms that the weaving is produced on.

How does Women of Visions influence you? What do you get out of being part of the group?

A handwoven shawl by LaVerne Kemp.

I appreciate all art forms and, of course, all art can be inspiring in one way or another. As a teacher, I am always taking classes of some sort to keep it fresh and exciting for my students. I have tried glass making, ceramics, and even a little painting and jewelry making. Each Women of Visions member and each exhibition brings forth something new and creative in my eyes and I have the other women to thank for that. But I have decided to stay in my element and stick with the softer side of the art world, with my fiber.

I have been told that I am the only African American weaver in Southwestern Pa. I know of two others who have passed away, so this might be true. To that end, I am a part of history. I’ve also been told that Women of Visions is the oldest African American women’s art group in the country, so again we are history, and I am proud to be of it. More than this, I feel good knowing that I have influenced so many others in my exhibitions and through my teaching. I have used the gift I was given.

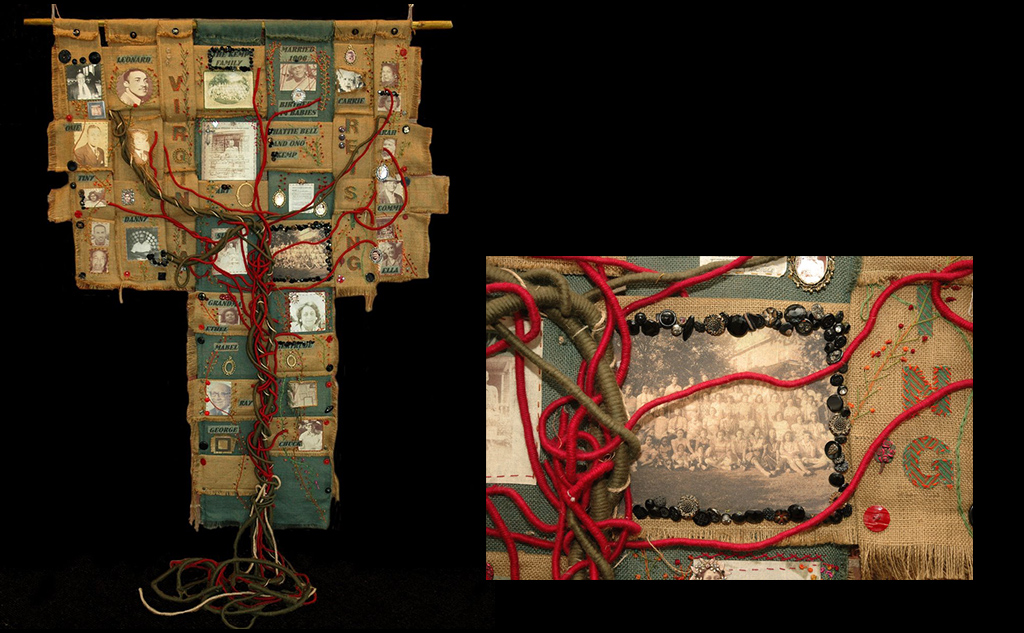

“Rooted by Blood: The Journey of Ono and Hattie Bell” by LaVerne Kemp, with detail inset.

Mary Martin—Communicating through Pottery

Mary Martin

I am primarily a ceramic artist, but I also work in metal, glass, and collage. Each medium informs the other. It’s like a call-and-response experience. This is part of my heritage as well. Music is just another means to communicate.

I love making functional pottery that is heavily adorned with carved or hand drawn lines, patterns, and textures. I love making teapots, bowls, cups, vases, etc. But I also make abstract pieces to express personal stories as well. I work using wax, underglaze, stains, commercial glazes. I work on the potter’s wheel and hand-build. I’m constantly being influenced by West and East African designs. I am strongly influenced by textile designs as well.

I also work in metals to create functional body adornment. Brass and copper mainly. And my collages are made of magazine imagery, papers, and paint.

Why do you, personally, make art?

I make art because I love to have a purpose. My artwork is a means to preserve traditions that would otherwise die out. Artists have a responsibility to preserve our traditions. We are meant to share our gifts with others. I believe that we are here to raise questions, but also to find solutions about life. Problem solving is such a large part of what I do. If there’s no struggle, I feel like the work isn’t complete.

How did you learn ceramics?

A teapot by Mary Martin

My educational journey has been very non-traditional. I grew up in a creative house. My father is a painter and a retired art educator for Pittsburgh Public Schools. I would watch him expressing himself in multiple mediums: watercolor, sculpture, and he also made handmade leather handbags.

I went to art school to study architecture at Rhode Island School of Design. We were discouraged from taking classes outside of our major, so there was only one ceramic class that I was able to take at RISD. After college, I grew frustrated with finding entry level work in local architectural firms. Looking back, those experiences really reflect the racism that still exists within that field locally, as well as nationally. So, my mother encouraged me to make an appointment to show my portfolio to Bill Strickland at Manchester Craftsman’s Guild. He told me that he didn’t have architectural work, but that I could choose any of the art studios to work as a teaching artist. I chose Ceramics and never looked back! It was a community environment where there were always at least four instructors in the space to teach different approaches to art making. I was mentored by Josh Green. He’s now the Executive Director of the National Council on Education for the Ceramic Arts.

Can you talk a bit about your ceramics tradition?

It was really interesting to discover that women are the primary artists working in clay in West Africa. I was really surprised to find this out, but I felt like I was part of a continuum, keeping that tradition alive. Like everything else, technology has replaced so many crafts that take time to create. It does feel like there’s a surge in folks wanting handmade art vs. factory-produced.

It’s a struggle to educate folks about the time it takes, though. I try to make pieces that are affordable by everyday folks so as not to cater to an audience that’s only wealthy. My works are appreciated by a wide variety of people. That excites me. I want everyone to have access to beautiful things, not just the wealthy.

I see my work as a continuum. It excites me to have a connectivity to an unbroken chain of artists with a common language. I know that some things that I make are subconscious decisions. It is exciting to discover an artist that connects with my work through the medium, process, content, or imagery. It’s that common language that runs deep as the rivers that Langston [Hughes] spoke about.

Two plates by Mary Martin

Broadly, what role does Women of Visions play in your art life? What is the value of this collective to you — professionally, artistically, emotionally, whatever?

WOV has been a major influence on my artistic growth as an artist.

My mother was in an African American female book club with a member of the group, Jacqueline Poindexter Jordan. She mentored me as soon as I relocated back to Pittsburgh from college. My first show was that summer, as part of the Harambee Black Arts Festival in Homewood. I was recruited to join the group when I dropped off my drawings for the exhibit. I was seeking other African American female artists to connect with and this felt like it. At the time, I was their youngest member, and I wanted to learn how to navigate the art scene in Pittsburgh.

The group has always brought about opportunities to stretch my imagination, to step outside of my comfort zone, and to step into administrative roles that I’d never thought I’d do well in. It’s offered me opportunities to grow professionally, artistically, and spiritually. I’ve always believed in collaboration, mentoring, and purpose. WOV offered all of these aspects.

As a mother, a daughter, granddaughter, aunt, niece, etc. I also feel that this group has been a constant reminder of femininity. It is one of the few spaces that I inhabit where I can be myself and see myself in other black female artists. I live the life of a chameleon, forced to change skins depending on the space that I’m in. WOV makes room for me unlike no other place. It’s about purpose, reciprocity, growth and identity. We support one another in ways that don’t happen in the workplace: I’ve connected with the members of the group with long term relationships that have been nurtured for almost three decades. My marriage, my children’s births, are all mapped with WOV experiences in mind. I can track any of these experience by associating them with one another. That’s how integral this is in my life.

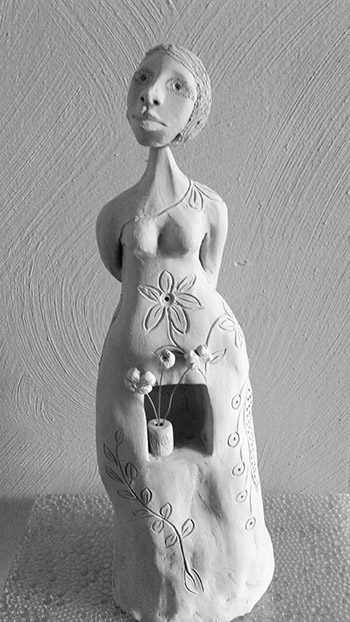

Janet Watkins—A (Second) Career in Ceramics

Janet Watkins

My passion for working with clay actually didn’t begin until after I retired from a 30 year career in banking. I was looking for an affordable hobby, then one day I noticed the beautiful church in my neighborhood posted a sign showing open studio pottery class. I stopped in, paid the hourly rate, and after one hour of working with clay I was amazed at the possibilities. I enjoyed the clay and process so much. In that short afternoon I discovered what I thought was merely going to be a new hobby.

What kind of ceramics do you create?

I usually work with brown earthenware, red clay, and porcelain. The type of work I create is mostly hand-built, functional, sculptural, and unique gardening art. I enjoy incorporating salvaged and discarded items into my work. I will often use items such as old, recycled telephone wire for hair, screws, bolts, old buttons, scrap wood & metal parts for added interest and texture for my artwork.

“Adolescent Girl” by Janet Watkins.

My passion for sculptural work comes from my early childhood time spent playing with dolls. And later in life, after retirement, spending time with my granddaughters making dolls out of playdough. I often find inspiration and attempt to repeat certain facial features of people I meet or just observe in conversation. I may talk with someone and notice they have unique or unusual eyes, nose, or face. There are often times when I will dream of a sculpture and wake in the morning, wanting to run to the studio and begin a new piece. It is so satisfying seeing the completed work. This form of art, I enjoy doing with my granddaughters, and I am passing it along to the two of them.

Why do you make art? What does it mean to you?

Coming up as a child both my parents were creative. Unfortunately, neither of them had the luxury of being able to be artists; they were much too busy working to make ends meet for me and my siblings. They raised us with the “can-do spirit”. They didn’t have extra money, so whenever we needed something, we found ways to make it. Example: when I got married, I made all of my bridesmaids’ gowns, the flower bouquets, and my wedding bouquets. We made our clothes for special occasions, such as prom gowns.

My career in art started just a short three years ago and I am still learning different techniques. I am what many would call a “shelf-made artist”. I work out of the little church where I first discovered clay — there is a very talented group of potters who are always willing to teach and share information.

How did you join Women of Visions, and how has it affected your art?

“Me Too Group” by Janet Watkins.

I knew about WOV for many years. In fact, I attended several of their exhibits before becoming a member. Two of the members visited my home and noticed a few items I had created. One member, Charlotte Kai, asked me if I ever thought of becoming a member of WOV.

In our group, we have many artists who work with several different mediums. This inspires collaboration between artists. As a new artist, I am still in the experimental phase. I have an appreciation for each artist and the medium which they chose to create from.

Exhibitions are a wonderful opportunity to grow, learn, experiment and challenge yourself. Sometimes you may create something based on a theme or title which you are not passionate or motivated about. This is exactly why I love being a part of this group. It’s in this type of situation where you learn and grow.

We as artists all enjoy creating. However, it’s important for me to be able to share my work, get feedback from my peers, and sell my work. By selling, I can purchase supplies and make space in my studio for more work.

Women of Visions’ website states that “We envision that in the next decade, we can create a visual record that places us in the annals of American history”. What does that mean to you, to be remembered in history?

We have a wonderful group of women from all different walks of life and different levels of work. Some have studied and taught art and some, like myself, are self-taught and still learning. I hope women, regardless of the color of their skin, can be encouraged and know you are never too old to begin a new career and learn something new. As for the group, what we share is a strong love of art and a desire to see each one of us be successful in our art form. We can be an example for all women for years to come.

A small figurine by Janet Watkins.

“Sitting Girl” by Janet Watkins.

“Soulmates Couple” by Janet Watkins.

Read more in the Heritage Highlights series. Our most recent story is on Mon Valley folk artist Kathleen Ferri.