Rachel Sager’s The Ruins Project

This week we are excited to honor what was—and what is—by shining a light on The Ruins Project, a long-term collaborative mosaic art installation amidst the ruins of a former coal mine in Fayette County, Pennsylvania. The brainchild of Rachel Sager, who operates the Sager Mosaics Studio, which is located near mile marker 104 on the Great Allegheny Passage, The Ruins Project represents the rebirth of abandoned American coal country into a spiritual and artistic pilgrimage and destination for adventure seekers and lovers of art and history.

By Rachel Sager, Guest Contributor

Rachel Sager at The Front Door of The Ruins

I have been writing about The Ruins Project for eight years now, and its ideal definition still eludes me. Like a slippery, Youghiogheny trout, it refuses to hold still long enough to be captured into the exact words that freeze it into the fullness of time.

But I keep trying. And with each try, I get a bit closer as I enjoy my wordy failures.

The Ruins is an ongoing outdoor art project built on the remains of an abandoned coal mine operation in Fayette County, Pennsylvania. It is a piece of architecture that embraces the excellence of contemporary mosaic art by using stone, glass, and ceramic to tell stories of place and time. It sits just off The Great Allegheny Passage bike trail that was once the Pittsburgh and Lake Erie Railroad.

To date, The Ruins cradles the art of over 250 artists from all corners of the world. Some of the best mosaicists working today are represented here. From Australia to Scotland, from India to Russia to Italy to Puerto Rico to Israel and dozens of U.S. states, The Ruins is a new recipe for the melting pot that started it all back in the late 1800s, when the original pot of immigrants dug coal here.

The art, installed carefully on its concrete and brick walls, ranges from delicately designed micro-mosaic native birds and portraits of real people who lived and died in the tiny coal-patch town of Whitsett to ambitious maps of countries that are creating a composition of the world. Mosaic bees, bats, mice, and cicadas represent the resilience of nature on this sleepy plot of land.

Possibly the biggest mosaic train in the world at seventy feet long anchors the architecture of The Ruins. Around moss-blanketed corners, visitors find surprises. Three full-sized mosaic quilts make up The Patch House Project, a collaboration involving more than 100 artists that celebrates the domestic side of the coal mining family.

The Great Train by Pittsburgh artist, Stevo Sadvary

But the main event is the coal miner.

I set in place a trio of rules the first year before any of the collaborative art was begun. The rules apply to everyone. The artists use them to make mosaic in ways that preserve the delicate balance of my vision. The rules also help the visitors to appreciate the story that is unfolding on deeper, more meaningful levels. As you experience The Ruins tour, your guide speaks to you about the bigger picture of time and how it changes a place.

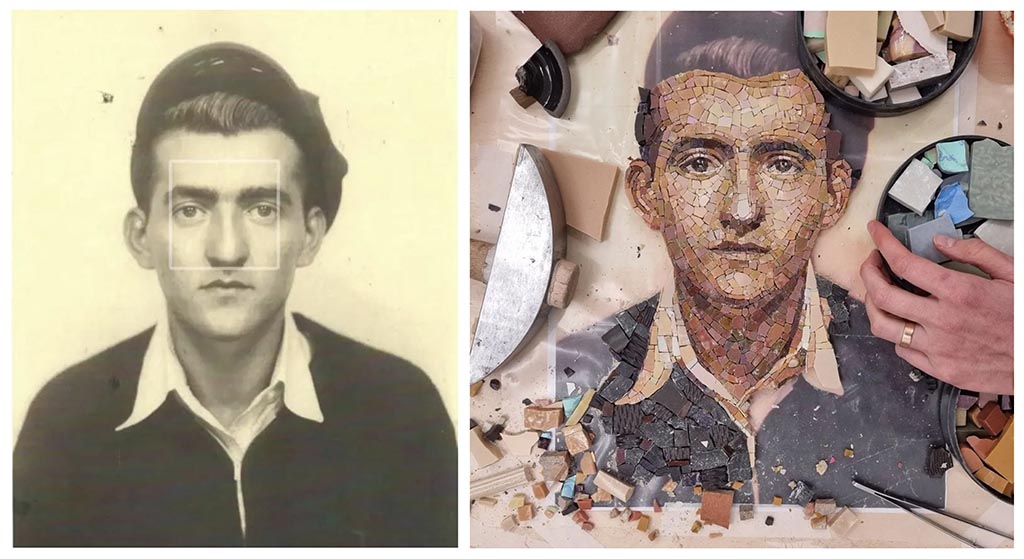

Photo of Charles Verba courtesy of The Whitsett Historical Society. Mosaic in progress by Russian artist, Adelaida Rosh

Rule #1 is to honor what was.

The man above is Charles Paul Verba, a miner killed in 1941 at the age of twenty-three in the Banning #2 mine. The classically trained Russian mosaicist Adelaida Rosh took on the challenge of recreating his photo into mosaic. The mosaic itself was carried from artist to artist on an arduous journey that spanned three continents this winter. It will be installed into The Portrait Room at The Ruins this spring.

With each careful portrait, I choose an artist, or sometimes she will choose me, who will honor the subject. When an emotional connection is crystalized between artist and subject, the process begins. I am hands off for this part as I consider it very important to let the artist interpret a person in their own unique way. Some end up quite realistic, like Mr. Verba above. Others can be more abstract, photorealistic, primitive, or even caricature. We have classically trained Ravenna artists and self-taught visionaries. (Ravenna, Italy is considered the mosaic capital of the world and is where many of the maestros in the art come from.) To date, we have ten portraits of men and women with many more in progress behind the scenes.

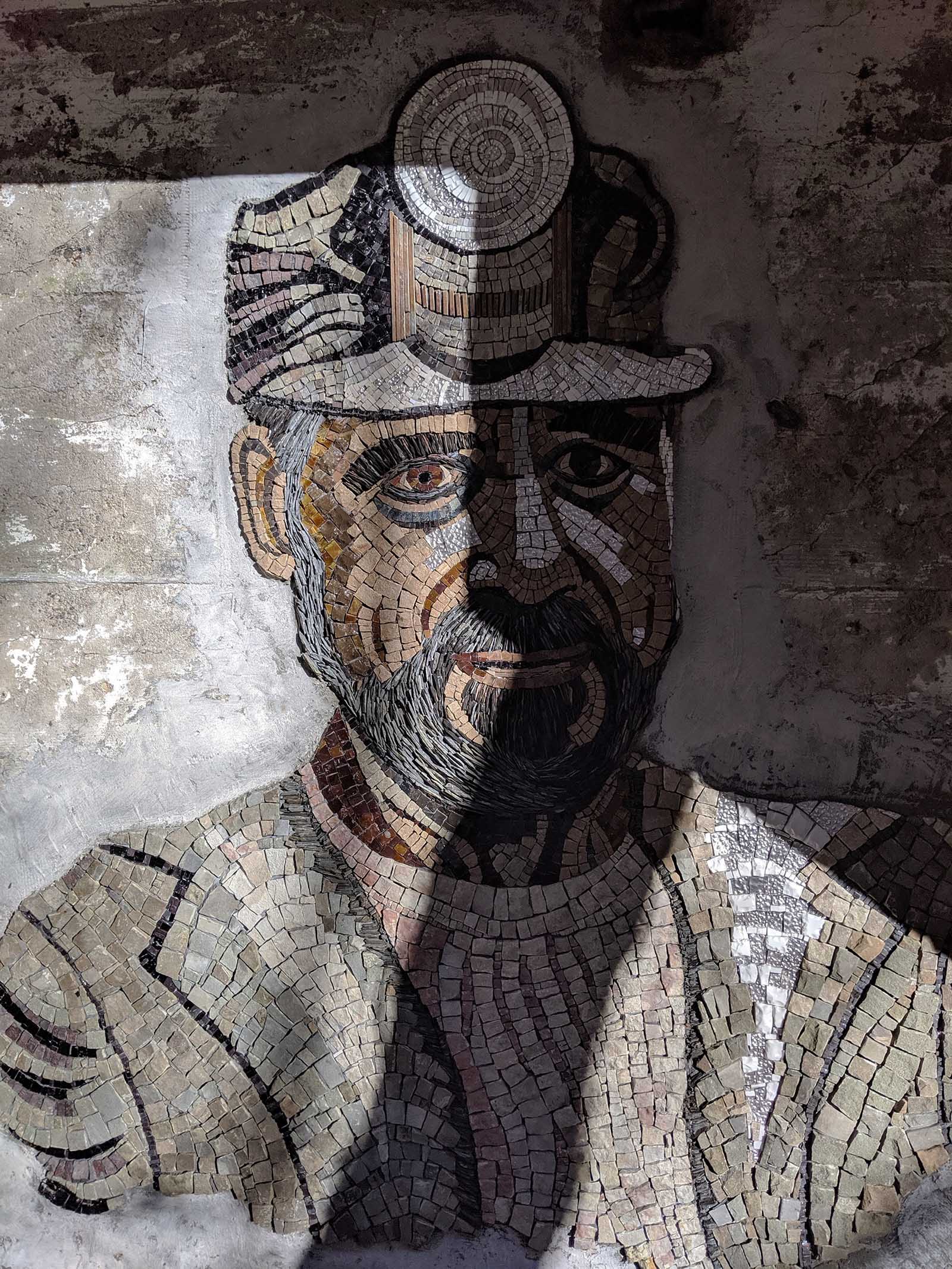

The Anonymous Miner by Wisconsin artist, Margy Cottingham

The Ruins portraits are a way to bring a person back to life. So many miners have been lost to time, their contributions swept under the rug of modern politics and our collective memory holes. I am consumed with an urgency to tell these stories while there are still descendants to help give us the details that are so important to storytelling.

We are finding that descendants will hear about the portraits of their grandfathers and husbands and uncles and come to visit. Good art makes you feel things.

The descendants of William Henry Mills with his portrait by Scottish artist, Joy Parker.

Geology is everything.

We ask visitors to picture a giant timeline that stretches from where they stand, down across the Youghiogheny River and over to the next patch town. That length of time is the primordial kind that is hard for humans to grasp. The best coal in the world took its time being made. And then another slice of time, about a horsehair width, is the fifty years it took men to find it, dig it, burn it, and turn it into the modern world.

The bituminous mines that radiated out and around Pittsburgh made Pittsburgh. The story we tell here spans not just back to the Industrial Revolution, but millions of years before. Before the dinosaurs. Back when giant horsetail ferns were growing and dying and creating the recipe for these coalfields. The Freeport seam. The Pittsburgh seam. The Connellsville seam.

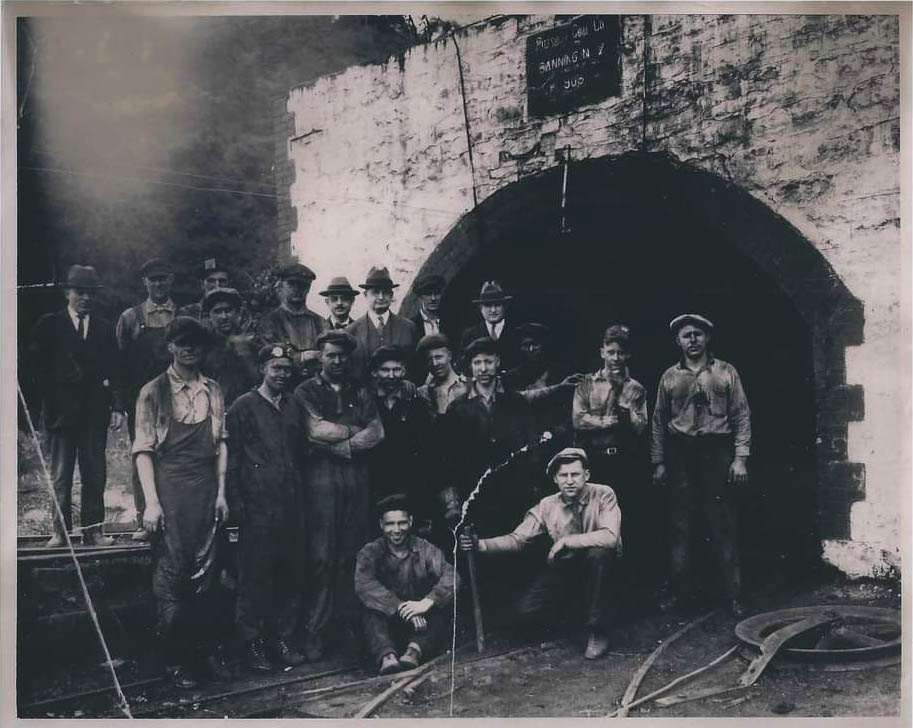

Banning #2 miners. Courtesy of The Whitsett Historical Society

I have memories of my father listing the layers of stratigraphy under his feet. His big-picture way of seeing the world helps me as I lay plans for the second decade of The Ruins.

It’s not an exaggeration to say that the Industrial Revolution was born here. The Pittsburgh Coal Company enlarged the portals that had been originally opened by smaller operations as early as 1893. The Banning #2 bituminous slope mine was called The Million Dollar Mine due to its very high production rate that spanned a short fifty years. The coal that men pulled out of these hillsides burned hot. Connellsville grade, they called it, and it fired well-known places like the Carrie Furnaces.

The coal that built the world.

My imagination travels the railcars that moved it to Youngstown, maybe even Detroit and Buffalo. Its circuitous routes took it to the Connellsville coke ovens, which then turned around and headed back to the steel mills of Pittsburgh. It was the literal fuel that created the backbone of our modern world.

The Carrie Furnaces, in miniature. A 2” x 5” micro-mosaic by Sager Mosaics installed at exactly the right spot of the Monongahela River on The Map Wall at The Ruins.

But there is more to The Ruins story than just the progress of industry. To take you deeper into understanding how this place cannot be defined, I need to take you back to my origin story. My father, grandfather, and great-grandfather mined coal in the Monongahela Valley. They owned and ran small drift-mine operations, loaded coal onto barges for home heating, and built our family from coal.

As I grew into an artist, I became aware that my peers and artistic community heard C-O-A-L as a four-letter word. I describe this uncomfortable time as my own personal Grand Canyon. I had one foot in the pride of where I come from and the other foot in the world of my progressive colleagues. I spent years full of angst, trying to find my place. And then, I bought my coal mine, and it gave me a stage, and it gave me courage to bring the two worlds together.

Let me take you back to that first rule. To honor what was.

It’s an odd phrase but chosen carefully. It doesn’t use the formal word history, although The Ruins is a very history-centric place.

Tour Program Director for The Ruins, Erika Johnson, installing The Ruins Angel, by Illinois artist Cindy Robin in The Memorial Chapel

Honor. What. Was.

These three simple words leave room for interpretation but ask for respect. Thousands of people from all over the world interact with this story, and I need to be sure that the memory of the people who worked, lived, and died here continues to be honored in spirit. By setting the tone of honoring first, all things are possible.

The Ruins is big. Its physical composition is big in that there is more of its concrete canvas to keep telling the story. And it is big in a philosophical way in that it gives people bridges. Long-dead coal miners and contemporary artists talking to each other through time and finding common ground.

This is the first in a series by Rachel Sager. Rules #2 and #3 will come in later publications and help round out the rest of The Ruins story.

Rachel Sager, The Storytelling Mosaicist, has been making mosaic, writing about mosaic, speaking about mosaic, and teaching mosaic for over twenty years. Her signature forager and intuitive teaching styles have changed how mosaic is experienced and have helped build on the golden age that the art form is enjoying in these exciting decades.

Rachel Sager, The Storytelling Mosaicist, has been making mosaic, writing about mosaic, speaking about mosaic, and teaching mosaic for over twenty years. Her signature forager and intuitive teaching styles have changed how mosaic is experienced and have helped build on the golden age that the art form is enjoying in these exciting decades.

As the owner and creator of The Ruins Project and Sager Mosaics, Rachel lives and works as an Appalachian entrepreneur in the hills and hollows of her hometown just down the river from Pittsburgh in Fayette County.

The easiest (and most engaging) way to keep up with what’s happening at The Ruins is by subscribing to The Ruins Substack which is also where you can find the growing episodes of The Ruins Podcast, a collection of conversations that Rachel hosts with all walks of creative people who interact with her cathedral to coal.

She hopes you will join her in her quest to unearth optimism; some days with a shovel, some days with a hammer, and some days with a pen.

The Ruins is accessible through guided tours only. To make arrangements go to Book a Tour.