By Brianna Horan | Image: An illustration of the Steamboat Arabia by Gary Lucy, provided by the Senator John Heinz History Center

Pittsburgh’s Time as a Steamboat City

Pittsburgh’s Time as a Steamboat City

What goes up must come down–that’s the easy part, thanks to gravity. Getting things to move in the other direction is the where the challenge usually comes in. For the feat of propelling a large amount of passengers and cargo against the south-flowing currents of the Mississippi River in the 1800s, the invention of the steamboat was revolutionary. Suddenly, merchants could transport their goods to new frontier settlements, expanding both the economy and the supplies available to pioneers in the nation’s interior.

Marked by their striking, steam-driven paddle wheels, these boats were made possible by the invention of the steam engine by Englishman Thomas Newcomen in the early 1700s. After a series of shaky attempts to combine steam engines and nautical travel, Robert Fulton, born near Lancaster, PA, refined the technology and built the Clermont in 1807—a flat-bottomed sidewheeler with a square-shaped stern that was initially dubbed “Fulton’s Folly.” After the Clermont consistently completed multiple roundtrip journeys between New York and Albany on the Hudson River, Fulton soon proved that his venture was popular and profitable, kicking off the first viable commercial steamboat service.

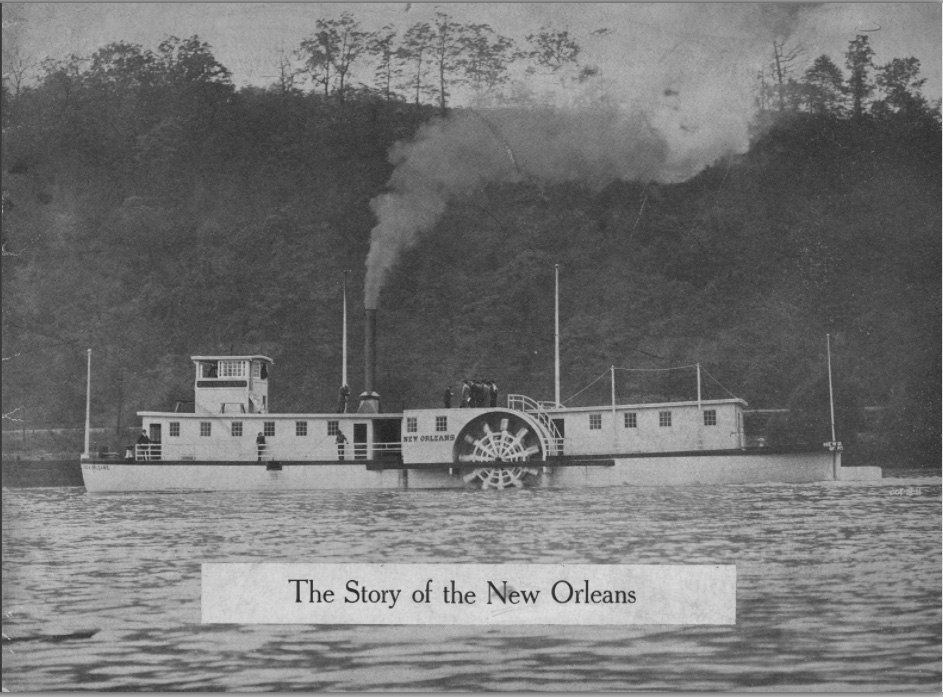

As is the case with so many stories of innovations that shaped America, the Pittsburgh region had a vital role to play in the steamboat industry’s history. The city became a steamboat hub after the Steamboat New Orleans set off here and became the first to complete the 1,800 mile journey down the Ohio and Mississippi rivers. The boat was funded by Fulton and Robert Livingston, a New York politician and inventor who helped to negotiate the Louisiana Purchase. Nicholas Roosevelt, who was a great-granduncle of President Theodore Roosevelt, oversaw the building of the Steamboat New Orleans in Pittsburgh, which he named for its ultimate destination. On October 20, 1811, Roosevelt and his wife Lydia, who was eight months pregnant with her second child, set out from Pittsburgh on the Ohio River to make history. The Senator John Heinz History Center’s blog tells the riveting story of this maiden steamboat voyage down the Ohio and Mississippi Rivers. It is highly recommended reading about a riveting journey that included a delay in Louisville caused by low waters at the treacherous Falls of the Ohio that was perfectly timed to allow Lydia to give birth, riverbanks crowded with people terrified by the unsettling sights and sounds of the strange steam-powered behemoth, and navigation through a series of the strongest earthquakes ever recorded in the eastern United States. The seismic activity caused the Mississippi to temporarily run backwards, new waterfalls were formed, islands were swallowed up as new ones were formed, and fallen trees created an obstacle course of snags that easily could have doomed the boat. The newly-enlarged Roosevelt family arrived in New Orleans nearly three months later, on January 10, 1812, proving that steamboat was a viable—if dangerous—way to connect the nation’s interior as western expansion intensified.

Cover of the book “The Story of the New Orleans, 1811-1911,” from the University of Pittsburgh’s Historic Pittsburgh Book Collection.

By the 1830s, nearly 40 percent of the nation’s steamboats were being manufactured in Western Pennsylvania, using locally-produced wood, iron, glass and paint. Mon and Ohio River Valley communities like Elizabeth, Brownsville, Belle Vernon, California, and Sewickley employed a large number of skilled craftsmen, launching hundreds of vessels each month. As the Heinz History Center’s communication assistant Katelyn Howard wrote for the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette in 2014, “The booming steamboat industry helped maintain Pittsburgh’s role as a key ‘Gateway to the West’ from the 1830s through the 1860s.“ By 1849, Pittsburgh’s wharf hosted more than 2,000 steamboats annually.

Steamboats were plentiful, but so were the dangers of traveling on one. The average lifespan of a steamboat was only a few years long. American waterways were filled with treacherous curves, fast currents, and variable water levels. The country was heavily forested at the time, and steamboats had to contend with numerous tree trunks floating beneath the surface—known as snags—waiting to impale and sink the vessels.

An illustration of the Steamboat Arabia by Gary Lucy, provided by the Senator John Heinz History Center

The Steamboat Arabia was one such boat that struck a snag while navigating the Missouri River, sinking in a matter of minutes. Luckily, all 130 people onboard survived – the only casualty was a carpenter’s mule who had been tied to the boat’s stern. It was thought that the 220 tons of cargo onboard were lost forever—a loss that caused several frontier towns to dry up after the Arabia failed to arrive with the clothing, tools, food, mail, munitions, and other supplies onboard.

The Arabia had been built at the boatyard of John S. Pringle in West Brownsville, PA, in 1853. This 171-foot-long steamboat sat at the bottom of the Missouri until the late 1980s, during which time the river’s path changed course. When a team of Kansas City, MO, locals learned the boat’s story, they were able to pinpoint the Arabia’s resting place – which ended up being 45 feet below a cornfield near Kansas City, a half mile from the present channel of the Missouri River. During a four-and-a-half month excavation, they uncovered millions of items in what was the largest collection of pre-Civil War artifacts – all perfectly preserved for 130 years in an oxygen-free environment.

These treasures are on permanent display at the Arabia Steamboat Museum in Kansas City’s River Market (check out their website for some incredible photos), and in 2014 the Senator John Heinz History Center hosted a special exhibit displaying some of the recovered cargo, called “Pittsburgh’s Lost Steamboat: Treasures of the Arabia.” The exhibition is now over, but luckily for us a thorough video tour guided by the History Center’s president and CEO Andy Masich is available online, where there are also a number of interesting facts and photos about the Arabia’s ill-fated journey. It’s fascinating to see goods made in western Pennsylvania and across the globe in the mid-1800s looking like new—including an assortment of clothing, bolts of fabric, jars of pickles, balance scales, fine china, tin ware, and even two prefabricated homes that were intended for frontier towns.

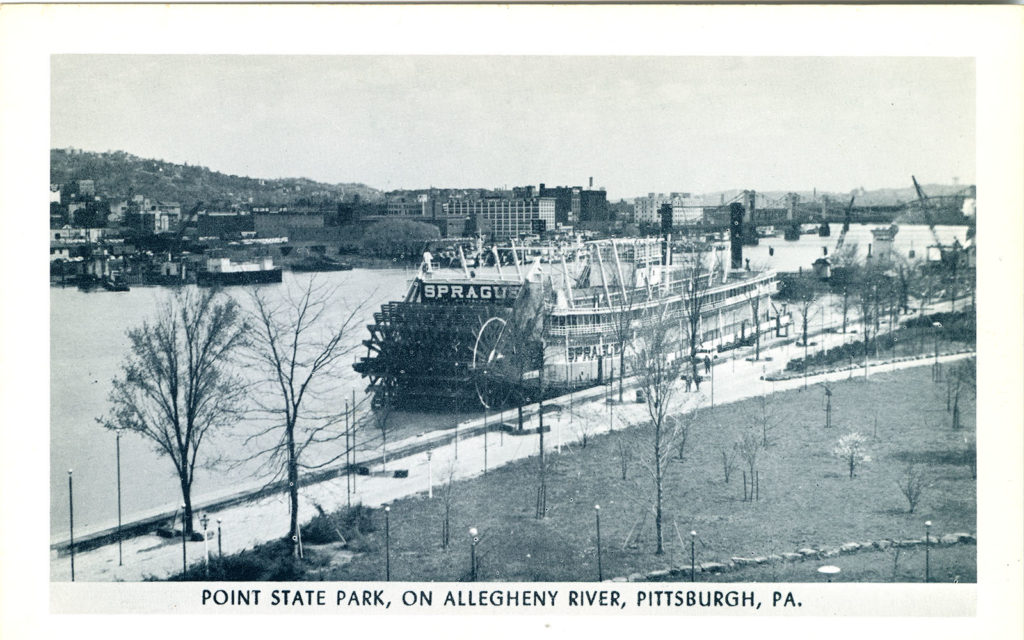

Postcard of the Sprague docked at Point State Park, 1959. Collection of Marilyn (Sprague) McCoy.

To bookend a story that linked Pittsburgh with a steamboat “first” is the story of a local connection to the biggest steam-powered sternwheeler towboat in the world. The 318-foot Sprague was built in Dubuque, Iowa, at the Iowa Iron Works, but it was named for Captain Peter Sprague, a marine construction supervisor who spent his early years in Elizabeth and Shousetown, PA, learning the boat building trade. He was known for having built or repaired one steamboat for every year of his 72-year-long life, earning him an induction in the National Rivers Hall of Fame in 2000. It’s noted that towards the end of the 19th century, Sprague was able to look from one end of Pittsburgh Harbor to the other and see that he had either built, designed, repaired, or rebuilt nearly every boat.

A panoramic view of Pittsburgh’s riverfront from the Pittsburgh and Lake Erie Railroad yards. The Smithfield Street Bridge is visible along with the Kanawha steamboat, docked on the Monongahela River, and several downtown business buildings including the Union Bank Building. From the University of Pittsburgh’s Pittsburgh City Photographer Collection, 1912.

In 1899, more than 90 independent coal operators in Pittsburgh were consolidated to form the Monongahela River Consolidated Coal and Coke Company, the largest river operation of all time. At the age of 71, Sprague took the job of overseeing the maintenance of the company’s fleet of more than 100 steam towboats. Soon after, the towboat Smoky City went up in flames in Pittsburgh in October of 1900. To fill the need to haul empty coal boats from New Orleans to Louisville, Sprague sat down to pen his final and finest design.

The finished Sprague was launched in September 1902, after her designer’s death. The massive vessel had to be towed from Dubuque to St. Louis to have her 40-foot paddlewheel installed because it was too long to pass through the Keokuk Lock in Iowa with the wheel attached. On her maiden voyage to Cairo, IL, the Sprague collided with a showboat called Temple of Amusement due to mixed up signals. The show boat was sliced in half and sunk in the incident. The Sprague also suffered damages, and she was taken to Pittsburgh to strengthen her structure and improve the signal system. Next came a successful run to New Orleans, after which the vessel returned to Pittsburgh for extra hog chains to be added to prevent the hull from sagging or “hogging” under heavy loads.

Before long the Sprague earned the nickname “Big Mama” in 1904 by pushing 53,200 tons of coal – only to break it in 1907 towing 67,307 tons of coal between Memphis and Baton Rouge, a 612-mile journey. The Sprague also set records for the number of tows lost; on one incident in 1913 she hit a stone dike near Osceola, AR, and let go of 35 barges carrying 53,200 tons of coal – enough to temporarily form a new island in the Mississippi River. Big River Magazine details the Sprague’s eventful life in a 2015 article by Connie Cherba and Harold Pollock called, “When ‘Big Mama’ Ruled the Rivers.” The Sprague’s paddlewheel kicked up a 10 to 14-foot wake behind it, and some claimed that the Mississippi ran backwards after the Sprague passed going upriver, with her wheel wash splashing the shore for hours after she went by.

Steamer Sprague arriving at Vicksburg with refugees for Red Cross care, May 12, 1927. Photography by the American National Red Cross. Collection of Marilyn (Sprague) McCoy.

In 1925, Standard Oil Company bought the Sprague to haul crude oil to Baton Rouge, LA,– more hauling records ensued. In 1927, “Big Mama” carried 20,000 refugees from Greenville to Vicksburg, MS, during a record flood of the Mississippi River. She continued to haul oil in service of the World War II, but after the war she was decommissioned at Memphis in 1948 in favor of more efficient diesel vessels. The Sprague was sold to the city of Vicksburg for one dollar in 1957, housing a popular floating restaurant and river museum.

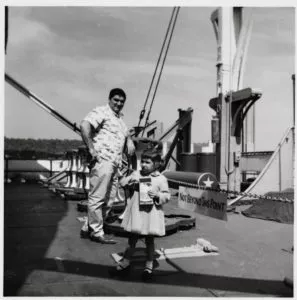

George and Marilyn Sprague on the Sprague, 1959. Collection of Marilyn (Sprague) McCoy.

In 1959, the Sprague made one more trip to Pittsburgh, towed to the Point in celebration of the city’s bicentennial. The Waterways Journal Weekly’s March 2008 “Old Boat Column” by Keith Norrington details the Sprague’s later years and the trip back to Pittsburgh. In preparation of the bicentennial appearance, “Big Mama” was treated to more than $100,000 of renovations and repairs before the Union Barge Line towed her 3,000 miles round trip on the Mississippi and Ohio Rivers. Thousands of visitors toured the Sprague while it visited the Point in the summer and fall of 1959; one of them was a young Marilyn Sprague, a distant relative of Captain Peter Sprague—take a look at the photo of her with her father, George Sprague.

The Sprague returned to Vicksburg in November 1959 and continued to draw tourists as a floating theater, showing Vicksburg Little Theater’s long-running melodrama, “Gold in the Hills.” Sadly, an overnight fire on April 15, 1974, gutted the Sprague, leaving only the sternwheel and hull intact. The remains of “Big Mama” stayed on Vicksburg waters for a few years after, until the flood of 1979 sank her. That wasn’t before Marilyn Sprague paid a visit to what was left of the world’s largest steam-powered towboat one more visit in Vicksburg in 1975.

Marilyn Sprague with the Sprague Sternwheeler, Vicksburg, 1975.

Pieces of the Sprague are strewn and rusting in overgrown riverfront property outside of downtown Vicksburg today. Marty Kittrell, a photographer there, has photographed these relics in an appeal to preserve the Sprague and its story on his blog. Today the Sprague can still be heard, thanks to a recording of her whistle from an LP recorded in 1965, shared by Steamboats.org (listen to the second recording to hear “Big Mama”).

The Sprague enjoyed a life that extended long into the 1900s, but for the most part steamboats began to decline as the preferred way of trade and travel after the Civil War, when railroads emerged as a more efficient mode of transportation.

Pittsburgh’s reign as a steamboat city may have been fleeting, but the craft of boat building and the pioneering spirit that grew out of that age are an important foundation of the region’s heritage.

Pittsburgh’s Time as a Steamboat City

Pittsburgh’s Time as a Steamboat City