Edith Darlington, a contemporary of Carrie Clark, on her wedding day is 1885, photographed by her brother O’Hara (detail). From the Darlington Collection at the University of Pittsburgh.

The Marriage of a 19th-Century Factory Owner’s Daughter

This story is the third in a series of articles about Carrie Clark Arkell, the woman who was the namesake of the Carrie Blast Furnaces. In this piece, Dr. Kirsten Paine examines the wedding of the young Miss Clark and gives context to what may have been expected from her as a young bride from a family with new wealth.

By Dr. Kirsten L. Paine

New Connections for Carrie Clark

Last month, we began to unpack the life of the namesake of the Carrie Furnaces, Carrie Clark, and explore the latter half of the nineteenth century through some significant events in her life. Attending Vassar Preparatory Academy and then Vassar College from 1878 to 1881 proved a significant period in her life because it exemplified a broader shift in Americans’ beliefs and investments in women’s education. Even a year spent in an academically rigorous institution like Vassar differentiated Carrie Clark from many other young women from wealthy Pittsburgh families. As we [re]introduce Carrie Clark to Pittsburgh history, we should also take a closer look at some of the ways she was very much like other women in her peer group and what we can learn about the experience of womanhood in post-Civil War America.

This week, I’m exploring some of the expectations, conditions, and assumptions that people in late nineteenth-century America placed on the institution of marriage. Carrie Clark married Bartlett Arkell in November 1886. We could ask a lot of questions about this coupling, particularly about whether or not their union was the “right” one—meaning, was their marriage a socially, economically, and politically advantageous arrangement, not only for Carrie and Bartlett, but for the Clark and Arkell families? This is a particularly interesting question for me because we do not yet have any real details about whether or not this was a relationship born out of love and affection, convenience and ambition, or a little bit of both. While it would be fun to write about a swoon-worthy romance, we simply do not have the letters, diaries, photographs, or other personal mementos that would make it possible at this point in our research. Perhaps someday. What we can do, however, is glean information from newspapers and look at how the Clark-Arkell marriage fits into a bigger cultural landscape.

In our previous piece about Carrie Clark’s education, I mentioned that she lived during a period of pretty drastic change that impacted nearly every aspect of a person’s day-to-day experiences. Industrial and technological advancements in manufacturing, transportation, and communication altered physical landscapes. Rail lines crisscrossed hills, valleys, and plains so trains could carry people all over the country. Telegraph lines crisscrossed hills, valleys, and plains so messages could be transmitted further and faster than ever before. Great distances were no longer considered insurmountable because people had new ways of communicating and therefore maintaining all kinds of relationships with each other. As social and familial networks expanded, the shape of those networks did, too, thus allowing more people from different places to impact each other’s lives.

Of course, the Clarks played an important part in creating the infrastructure that allowed people to experience life beyond the boundaries of their home environments. Between the Solar Iron Works (1869) and the Carrie Furnace Company (1884), the Clark family’s investments in iron manufacturing technology helped make it possible for people to live, travel, and talk to each other in more immediate ways.

Parisian fashions in Peterson’s Magazine, October 1885, show what women of means may have been wearing at the time of the Clark-Arkell wedding. From the Library of Congress.

Nineteenth-Century American Marriage

American marriage, as an institution, changed a lot throughout the nineteenth century. Before the 1850s, married women in the United States, regardless of class, were largely subject to laws of coverture. Simply put, marriage as a set of laws required women to surrender property, money, business interests, and other discernible capital to their husbands. They ceased to exist as a separate entity and were subsumed into their husband’s estate as part of the estate holding itself.

It wasn’t until some states passed married women’s property acts in the 1830s and 1840s that women were granted the ability to own and control their own property after marriage. Additionally, it was not until the late nineteenth century that married women gained the right to business ownership or their own wages from either employment outside the home or business investments. Economically advantageous marriages involved the transfer of property and the protection of investments, land, or other business holdings. There was little incentive for cross-class marriages unless one family held significant interest or promise of another, and women often played important parts in securing or protecting capitalistic interests because they themselves retained power as capital.

By the time Carrie Clark and Bartlett Arkell married, women could legally retain property and business ownership, although Carrie likely surrendered most, if not all, of the decision-making power outside the home. Women’s primary duty within marriage was that of household manager. Wives usually managed domestic finances, such as day-to-day purchases of food, clothing, and any necessities for the house. Wives also oversaw child-rearing, as children were a direct reflection of family unity, piety, character, and success. Well-to-do wives, especially women like Carrie Clark, were expected to cultivate a home life reflecting their family’s social standing. They needed to decorate according to modern tastes and standards, and this included cultivating the appropriate social networks, philanthropic activities, and any other domestic labor dedicated to making sure the family’s character and prospects were unsullied.

This is not to say that marriages were only contractual exchanges designed to control property, money, and children. People in the nineteenth century married for the same reasons people marry in the twenty-first century: for love, for romance, for companionship, and for family—and we have no reason to say that twenty-three- and twenty-four-year-old Bartlett Arkell and Carrie Clark married for any other reason than they were madly in love with each other.

The Clark-Arklell Wedding Announcement

Carrie Clark and Bartlett Arkell: A Match Made in …

We do not know when or how Carrie Clark and Bartlett Arkell became acquainted with one another, and we do not know the personal circumstances surrounding their courtship or what prompted their engagement. It does, however, seem likely that this was a relationship that took several years to develop. Carrie Clark attended Vassar College for the 1880–81 school year. Vassar is located in Poughkeepsie, New York, and its historical counterpart, Yale University, is seventy-five miles away in New Haven, Connecticut. Bartlett Arkell graduated from Yale University in 1886. The relationship between the two institutions increases the likelihood that Clark and Arkell’s paths crossed somewhere in that seventy-five-mile radius.

By 1886, Carrie Clark benefited from familial wealth and prominence in Pittsburgh. The Carrie Furnace Company churned away on the Monongahela River while the Solar Iron Works, now under her brothers’ management, continued its own output on the Allegheny River. The Clark family lived in Pittsburgh’s well-to-do East End, somewhere near the modern-day intersection of Shady and Penn Avenues.

Bartlett Arkell had a similar pedigree. He was the son of New York State Senator James Arkell, a wealthy businessman-turned-politician from Canajoharie who placed his sons in advantageous, upwardly mobile careers in shipping and publishing companies. By 1886, Bartlett Arkell had graduated from Yale University and started on a path that would lead to the establishment of the Beech-Nut Packing Company.

The Clark and Arkell families occupied similar positions in their respective communities. They were wealthy industrialist investors who carved out visible roles in colorful social circles. At the dawn of the Gilded Age, neither family was considered old money, which meant they also had limited access to entrenched social circles out to protect their accumulated wealth and power rather than expand it even more. The newly wealthy networked with each other in hopes of creating ambitious connections in the establishment of power and influence. One group wanted to maintain their control of elite American enterprises and institutions while the other—the group to which the Clark and Arkell families belonged—wanted to expand, to conquer, and to be written about in the annals of American history as equals. By every measure, Carrie Clark and Bartlett Arkell’s marriage exemplified the pinnacle of upwardly mobile families throughout the mid-nineteenth century. They were the ideal, young, worldly, affable, social focal point of two extremely ambitious families. The Clark-Arkell match should have ushered in a new era, not unlike their near counterparts Henry Clay and Adelaide Frick.

The announcement, appearing in the June 19th, 1936 edition of The Record, includes a reproduction of a photograph showing Mary Carolyn Arkell in her wedding dress, replete with an enormous bouquet of flowers.

Engagement and Wedding Announcements

We know only a little about Carrie Clark and Bartlett Arkell’s wedding and subsequent marriage. An Allegheny County Marriage License Docket, entry 4377, shows Bartlett Arkell applied for a marriage license that was issued on November 26th, 1886, and that the marriage took place on November 30th. The Morning Journal Courier, a newspaper published in New Haven, Connecticut, printed the following on November 20th, ten days before the wedding: “Cards announcing the wedding of Miss Carrie Clark of Pittsburgh, Pa., and Bartlett Arkell ‘86, a son of ex-senator Arkell of Canajoharie N.Y., have been issued.” There is no further information about the time, place, or attendance of their wedding. A full announcement in local newspapers’ society columns about Carrie Clark’s wedding seems like a significant missing piece to Carrie Clark’s biographical puzzle.

What should a socially appropriate wedding announcement for Carrie Clark look like? Here are two excellent examples. In 1936 and 1943 respectively, two New Jersey newspapers announced the weddings of the granddaughters Carrie Clark never knew. Mary Carolyn Arkell, William Clark Arkell’s oldest daughter, married a man named Harry Francis O’Hara. The announcement, appearing in the June 19th, 1936 edition of The Record, includes a reproduction of a photograph showing Mary Carolyn Arkell in her wedding dress, replete with an enormous bouquet of flowers. The announcement reads, “Mrs. Harry Francis O’Hara Jr., who was Miss Mary Carolyn Arkell, daughter of Mr. and Mrs. William Clark Arkell of 227 Maplewood Ave, Englewood, before her marriage to the son of Mrs. Dion Keith Kerr of Chevy Chase, Md. The wedding took place in St. Paul’s Episcopal Church of Englewood.” The announcement, though brief, includes significant detail establishing the community standing of both bride and groom and their families by providing the Arkell family’s address (showing they live in a good neighborhood) and their home church (noting denomination and congregation). The picture of Mary Carolyn Arkell shows a young woman in a fashionable wedding dress. For 1936, this wedding announcement is period appropriate and adheres to general social expectations regarding the daughter from a wealthy family.

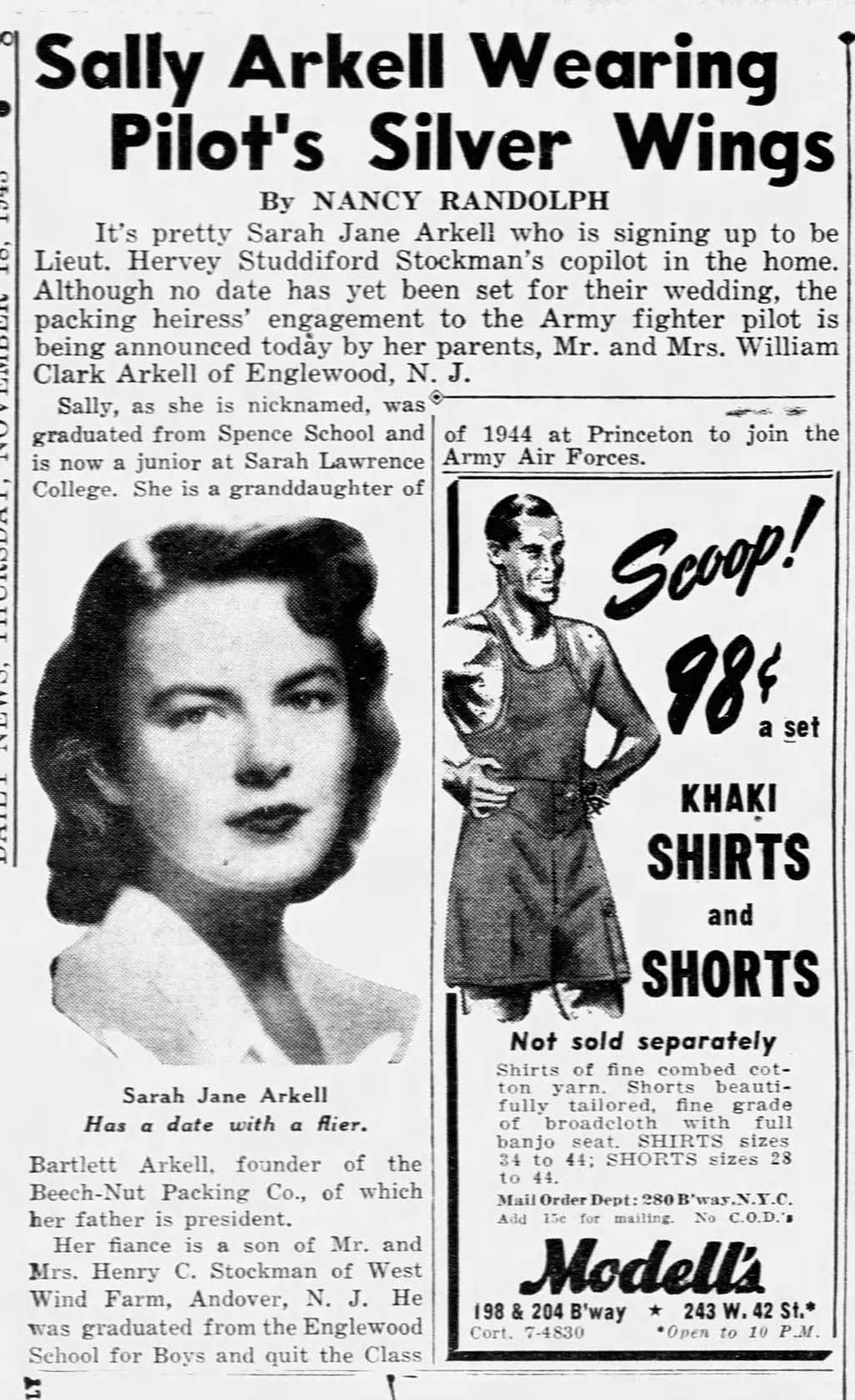

The announcement appeared in the November 18th, 1943 edition of New Jersey’s Daily News, titled: “Sally Arkell Wearing Pilot’s Silver Wings.”

Sarah Jane Arkell’s engagement announcement is altogether more fabulous than her sister’s, despite—or perhaps because of—being married in the middle of World War II. The announcement appeared in the November 18th, 1943 edition of New Jersey’s Daily News, titled: “Sally Arkell Wearing Pilot’s Silver Wings.” Sarah Arkell married Lt. Hervey Studdiford Stockman, an Army Air Corps fighter pilot. Their engagement announcement has all the hallmarks of a splashy social affair of the season, where their wedding would be the place to see and be seen. It is written as pure romance, as “pretty Sarah Jane Arkell who is signing up to be Lieut. Hervey Studdiford Stockman’s copilot in the home.” Sarah Jane Arkell, here noted as “the packing heiress” and “a granddaughter of Bartlett Arkell,” is characterized as a lovely, adventurous, well-educated, and rich young woman. Arkell “has a date with a flier,” and the included picture of her matches that of any Hollywood studio starlet from the mid-forties. The engagement announcement also details Arkell’s educational background at both the prestigious all-girls Spence School in New York City and Sarah Lawrence College, an equally prestigious all-women college in upstate New York. Stockman, her fiancé, left Princeton to enlist in the Army Air Corps. Like her sister’s wedding announcement seven years before, the write-up contains all of the necessary information to establish this as a good match between good families, thus meriting attention, broad approval and, with the appropriately patriotic overtones, worthy of a particularly celebratory moment in the midst of war.

Both of these announcements amplify the absence of such a notice about their grandparents’ own wedding on November 30th, 1886. This is what Carrie Clark should have had in The Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. Carrie Clark and her family had enough social, political, and economic standing in Pittsburgh to warrant money spent on copy like this. It is a kind of gap or silence that prompts more questions about Carrie Clark’s own wedding and subsequent marriage, but they are questions we cannot—and perhaps will not—have the ability to answer. Why is there no long-form article announcing Carrie Clark’s engagement or wedding to Bartlett Arkell? Were there any extenuating circumstances preventing the publication of that kind of feature? Did the Clark family prefer to keep her engagement quiet, considering William Clark was dead and therefore had no discernable social cache? Is there a piece of ephemera tucked away in an archive, or perhaps more likely, affixed in the pages of a scrapbook, that could yield more information? What happened to what should have been Pittsburgh’s social event of the season?

Marriage, Short-Lived

In the end, Carrie Clark and Bartlett Arkell were married just shy of two years. Carrie died on November 17th, 1888. That alone explains why Carrie was not named in Sarah Arkell’s engagement announcement. Why did Carrie Clark die when she was only twenty-five years old? Next time, we will explore death and dying in nineteenth-century America and what might have happened to cut her life so tragically short.

Dr. Kirsten L. Paine is an educator and researcher with more than a decade of experience working in higher education. She started working for Rivers of Steel in 2017 as a tour guide at the Carrie Blast Furnaces National Historic Landmark and was inspired by the mission to preserve such a national treasure held in public trust. Kirsten is committed to the work of public humanities education in her role as Site Management Coordinator and Interpretive Specialist. By creating and facilitating public programs that make the National Heritage Area’s history come alive for the community, she believes in archival study and teaching from primary sources as vital community resources.

Dr. Kirsten L. Paine is an educator and researcher with more than a decade of experience working in higher education. She started working for Rivers of Steel in 2017 as a tour guide at the Carrie Blast Furnaces National Historic Landmark and was inspired by the mission to preserve such a national treasure held in public trust. Kirsten is committed to the work of public humanities education in her role as Site Management Coordinator and Interpretive Specialist. By creating and facilitating public programs that make the National Heritage Area’s history come alive for the community, she believes in archival study and teaching from primary sources as vital community resources.

Enjoy Dr. Kirsten L. Paine’s article? Read her description about the discovery of Carrie Clark.