By Ryan Henderson, Interpretive Specialist

John Hughey & the Legacy of Black Workers at the Carrie Furnaces

John Hughey & the Legacy of Black Workers at the Carrie Furnaces

A Segregated Workplace & A Segregated City

As a major hub for metal production at the turn of the 20th century, Pittsburgh attracted workers not only from across the United States, but across the globe. Though work in the mills was difficult and dangerous, it was plentiful; the mills that lined the three rivers would hire men with little to no experience, with no shortage of positions waiting to be filled. While the first British and German settlers of Pittsburgh came with iron and other metal working knowledge, the successive waves of immigrants who followed often did not have backgrounds in iron or steel. Indeed, international newcomers to the region often spoke little English, let alone had familiarity with metallurgy. Still, these immigrants were able to find a place in Pittsburgh society and began to carve out niches for themselves within the workplace. As a result, Pittsburgh rapidly became a multicultural and multiethnic metropolis during the late 1800s and early 1900s. The many ethnic neighborhoods, churches, and cultural institutions that form Pittsburgh today are a direct result of this era of domestic and international immigration to the city.

However, while many Pittsburghers are familiar with the positive legacy of this era—pierogis, the Jazz culture of the Hill District, the Little Italy district of Bloomfield, heritage groups like the Tamburitzans dance troupe—there is a darker, often unacknowledged element to Pittsburgh’s multiculturalism and industrial culture. While each successive wave of newcomers added to Pittsburgh’s growing diversification, they existed within a firmly established ethnic and racial hierarchy. Those earliest, Anglo immigrants enjoyed power and privilege at the top of this system, while those that came after them—Italians, Poles, Slovaks, and others—had to work to gain entry into this power structure. The same ethnic neighborhoods that Pittsburghers treasure today are, in some part, the result of segregation on cultural lines, self-imposed or otherwise. This hierarchy affected not just social life but working life as well. Access to certain industries was in some cases reliant on having the right ethnicity, with some jobs in the mills restricted to those with certain backgrounds.

While many Pittsburghers suffered discrimination under this system, no group had a harder time finding entry into Pittsburgh’s industrial working class than its Black citizens. Black Pittsburgh was largely segregated from traditionally white parts of the city and, additionally, Black workers found it difficult to enter into predominantly white professions. For much of the latter part of the 1800s, Black workers primarily were known in the mills as strikebreakers, hired by management to help end labor disputes. Some of these strikebreakers, though not all, had become skilled laborers after being forced to work in iron production under slavery, allowing management to go around the specialized skill sets of their striking workforce.

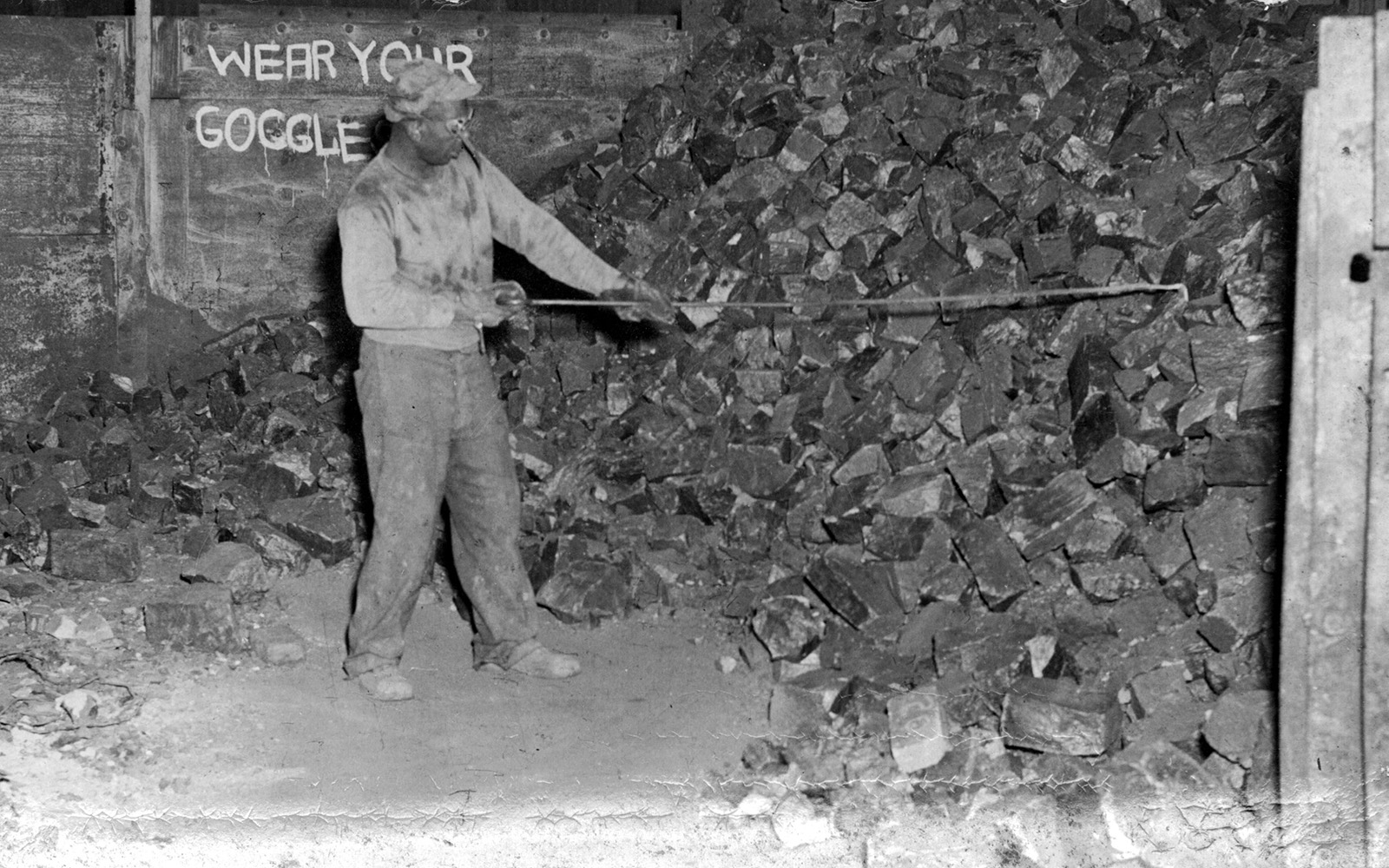

Ladle being settled into place for transportation.

The use of Black strikebreakers in this manner was a calculated choice on the part of management, as it increased tensions along racial lines. Unions in the late 19th century would not accept Black workers for this reason, as well as racist reasons more generally. This, in turn, proved to be a self-defeating mechanism for unions, as their refusal to admit Black workers created a ready-made strikebreaking force any time labor disputes broke out. At the same time, management continued to marginalize Black workers by electing to exclude them from many positions at mills, keeping them from being able to solidify power within mill culture and carve out a niche for themselves the way other ethnicities had. When they were employed, it was in the worst conditions, being given the most dangerous and unpleasant jobs.

Following the Homestead Strike of 1892 and the victory of management over labor, the issues surrounding union membership became somewhat moot as the union system collapsed for nearly 40 years. This did not help Black workers however, as their usefulness to steel and iron companies diminished with the less frequent need for strikebreakers. While their services would occasionally still be called upon, Black workers in this period saw what little place they had in the mill continue to erode, even as the city’s Black population continued to grow as a result of the Great Migration.

As the previous generation of Black workers had never truly been able to create a system of ushering newcomers into jobs the way other ethnic groups did, many of these new immigrants entered the workforce in other sectors. It was not until after the reformation of the union system in the late 30s and, more importantly, the end of World War II that Black workers were able to enter Pittsburgh’s industrial workplace in great numbers. Following the passage of the various legislation friendly to unions in the early 1900s and, several decades later, the conclusion of World War II, unions began to truly re-enter the iron and steel industry, forcing companies to recognize them once more. This time, unions accepted Black workers into the fold, in part to avoid the issues with strikebreakers that had affected them in the past.

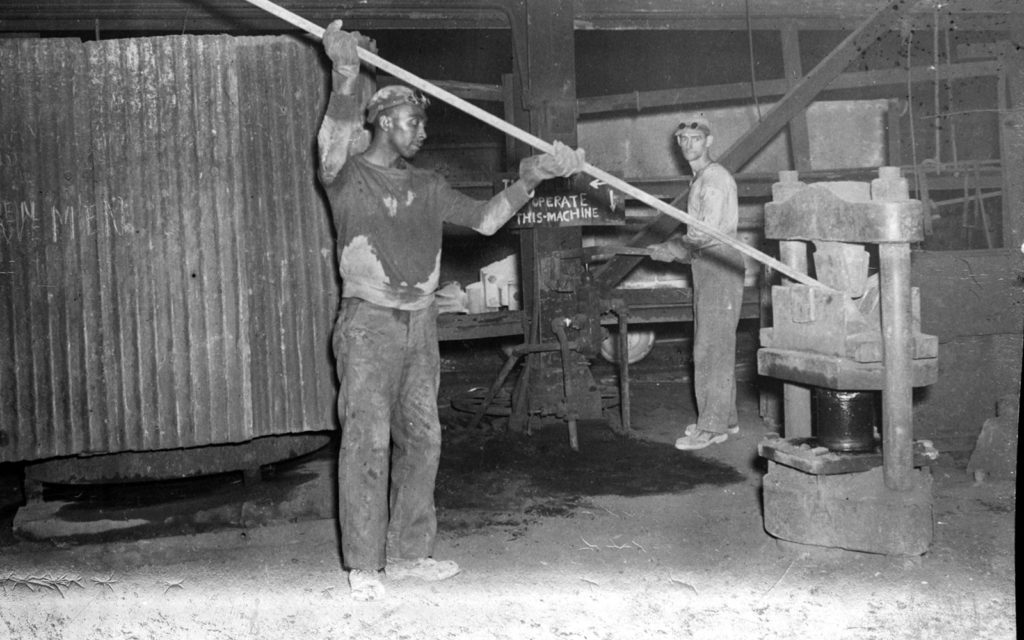

A worker bending a metal bar into a hook for various tasks at the mill.

John Hughey

An example of the life of a steelworker and ironworker post-WWII can be found in the story of John Hughey, who was employed at the Carrie Furnaces from 1947 through 1982, when the mill ceased production. Mr. Hughey was born in 1925 in Rankin, PA, a community that surrounded part of the Carrie complex. John’s father had moved to Pittsburgh in 1919, coming from South Carolina. He had been recruited by a man who spoke of better jobs and opportunities up north, and the possibilities that would come with working in the booming steel industry in Pittsburgh. Seeking that better life, John’s father moved to the Pittsburgh area, where he was placed in the Edgar Thomson Works in Braddock. What John’s father had not been told was that he would be coming to break a strike. While John’s father found employment for a period as a strikebreaker and gained new skills in the mill, he was dismissed shortly after the end of the strike. Though John’s father was an able worker, he was not white, and Black people with ability did not have mobility in this period. He became instead a door to door salesman, but the steelworking spark in the Hughey family did not end with him.

It was John who would become a lifelong metalworker, starting at the Carrie Furnaces at 22 years of age. Many young men in this era, including John’s other family members, worked for at least a few seasons in the mill. Many whites in Pittsburgh followed a kinship method of entry into the mill—their father would ask the superintendents to hire their sons, with multiple generations working in the same location. John did not have this same opportunity, and instead walked six minutes to the nearby Carrie to apply for a job. He was hired on the spot, to his surprise, making about $1.85 an hour.

Though John was unaware at this time of the politics surrounding the Homestead Works, this was consistent with the general hiring practices at Carrie. Carrie was the iron side of the Homestead Works, producing the liquid iron that would be transported across the Monongahela River to be turned into steel. Ironmaking, as well as producing coke, was generally considered to be the “worst” job within the steelmaking process. Ironmaking and coking are dangerous, smelly, and extremely dirty. As a result, these jobs were relegated to those individuals who were of ethnic and racial backgrounds that were at the bottom of the socially-constructed hierarchies that existed. In the early part of the 20th century, this meant Eastern Europeans. After Blacks entered the mill system in large numbers following WWII, this meant them. Two men, one Black and one white, both applying to work at the Homestead Works, would likely find themselves steered in different directions. The white man, especially if he was of Anglo descent, would find himself turned toward the steel side of the river. The Black man, almost always, would find himself pushed in the direction of the Carrie Furnaces.

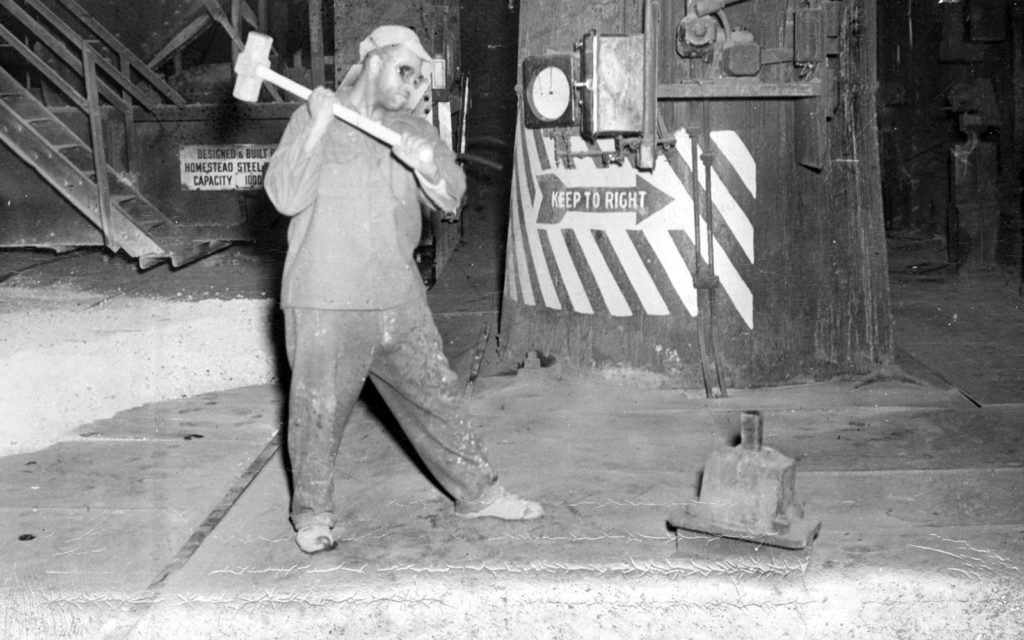

A worker lifts a sledgehammer.

Indeed, even the internal work divisions within Carrie were segregated. On the second night of work, John found himself “promoted” out of the position he was hired to and into the furnace division at Carrie, responsible for duties such as the actual tapping of the furnace. Without any training—a standard practice at the time—John was made into the second helper on Furnace #2.

John had no idea what was going to happen, standing around for hours before being directed to help with the tapping of the furnace—watching with both fear and awe as liquid iron came rushing forth; the 2,700 degree metal flowed like water a few feet away from him. John had been given only an asbestos coat for protection. He had no hardhat, worker’s greens (fire resistant clothing), or other heat equipment, only his street clothes.

Though John kept on as an ironworker, he later noted that this shock treatment was typical for the industry, where 20 men would be hired at the beginning of the day, and 15 would quit by the end, winnowing out all but the hardest men. John would later come to realize that his placement and lack of gear in the hot and dangerous furnace division was also no accident.

At the time he was hired, John guessed that the furnace division was 99% Black, and severely underfunded with safety equipment. Many men’s street clothes burst into flame in the cast house, and burns and blisters were common. Workers there had to buy their own gloves, and any protective equipment they needed. The maintenance division, on the other hand was composed of electricians, painters, carpenters, and other skilled workers and was almost 99% white. These jobs were considered prime positions, avoiding the dirtiest and most dangerous work, and for years were effectively whites only. They often had safety equipment bought for them; workers in the furnace division, meanwhile, would not receive basic gloves from the company until the 1970s. Other divisions also were heavily segregated, with John recounting that the Trainsmen’s Union, separate from the Steelworkers Union, explicitly banned Black membership until the 1950s.

At the time of John’s hiring, the Steelworkers Union was far from equal. “Last to be hired, first to be fired” applied to many Black workers, as they were purposely left until the very end to be hired into positions, and found themselves the first to be laid off in slow economic periods. In theory, the union system should have provided a kind of equality under its regulated system of benefits and advancement, but many Black workers did not experience the same successes as their white peers.

For example, the union ostensibly guaranteed a standardized wage system within the mills that would see a Black and white worker who started at the same job at the same time paid the same. However, it quickly became apparent that while white workers would eventually advance out of these starting positions, many Black workers were left to fruitlessly bid for higher paying, more sought-after jobs.

Work culture for the men who worked in the mills was unique but was still a reflection of the racial attitudes of U.S. society. While working in the dangerous conditions of the mill frequently left men with a sense of camaraderie that transcended racial lines, this was often not able to overcome long simmering prejudices that existed outside the mill’s walls.

This only began to change with the hard work of men like John, who fought to ensure rights for Black workers in the industry. In fact, John and other Black workers at Carrie found themselves in a unique circumstance created by the segregation between the two sides of Homestead; Carrie was, for much of its history after WWII, a majority Black mill. In the peak production period post-WWII, a large proportion of Carrie’s working population was Black, with over 90 percent of unskilled labor and 60 percent of the overall labor force being composed of Black workers.

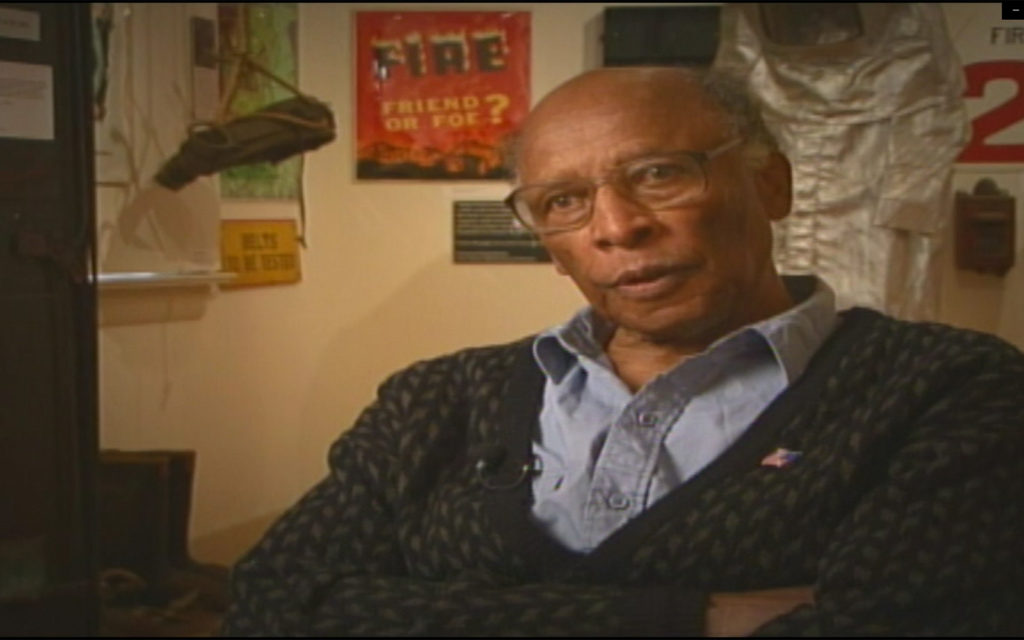

John Hughey

Years later, John recalled that Carrie was almost uniquely liberal in the Mon Valley, and while there was certainly tension in the mill, many important positions at Carrie were, nonetheless, held by Black men. All of this meant that John and other Black workers had a much clearer path to holding union offices through millwide elections. In 1949, a mere two years after starting at Carrie, John became a union grievance officer, one of the men responsible for taking issues to management to be resolved on behalf of union members. Five years later, in 1954, John became head grievance officer for Carrie, a position he held for many years.

Though John had to hold this position while also working a full time job in the mill—something uncommon for many grievance officers—he helped to lead several important fights that improved the lives not only of Black mill workers, but of all men who worked at Carrie. He and others pushed for company provided safety equipment, winning things such as greens and better heat gear. The union also pushed for dental and eye care, unheard of in the steel industry, and carried out a strike for better pensions. At Carrie, John helped lead a drive from 1954 that lasted almost 20 years until 1971 to have seniority count as the determining factor for advancement, rather than race.

The union at Carrie made many small advancements over this period leading toward success, to the extent that by the time a consent decree made mandatory changes to the steel industry to protect the rights of minorities, Carrie was already meeting proposed industry-wide standards. Indeed, by the 60s and 70s, Carrie had more minorities in trades than any other mill in the Mon Valley; in contrast, just across the river at the connected Homestead Works had a mere 1%.

John’s hard work, and the hard work of all those fighting for equal treatment, had a tangible effect. John and others noted a difference particularly after 1971, finally achieving a breakdown of the walls that had kept Black workers from certain jobs in the mill, and having ability counted over skin color. These men fought hard to create a better life and workplace that had eluded Black Pittsburghers for so long, and their legacy as pioneers in the field lives on today.

The accompanying photographs are part of the Rivers of Steel Archives.

If you like this article, you may want to read Josh Gibson Gets His Due, another story that examines the Black experience as part of the culture around our region’s industrial history.

John Hughey & the Legacy of Black Workers at the Carrie Furnaces

John Hughey & the Legacy of Black Workers at the Carrie Furnaces