Drag Queen Story Hour with Akasha Van Cartier

Heritage Highlights

Rivers of Steel’s Heritage Arts program strives to represent the region’s diverse cultural heritage, from ethnic customs and occupational traditions directly linked to Pittsburgh’s industrial past to new American folk arts and cultural practices emerging from the region’s diverse urban experience. Usually passed down from person to person within close-knit communities, these cultural traditions are as varied as they are unique, each representing one aspect of what makes southwestern Pennsylvania’s heritage so rich.

An Interview with Akasha Van Cartier

By Jonathan Engel

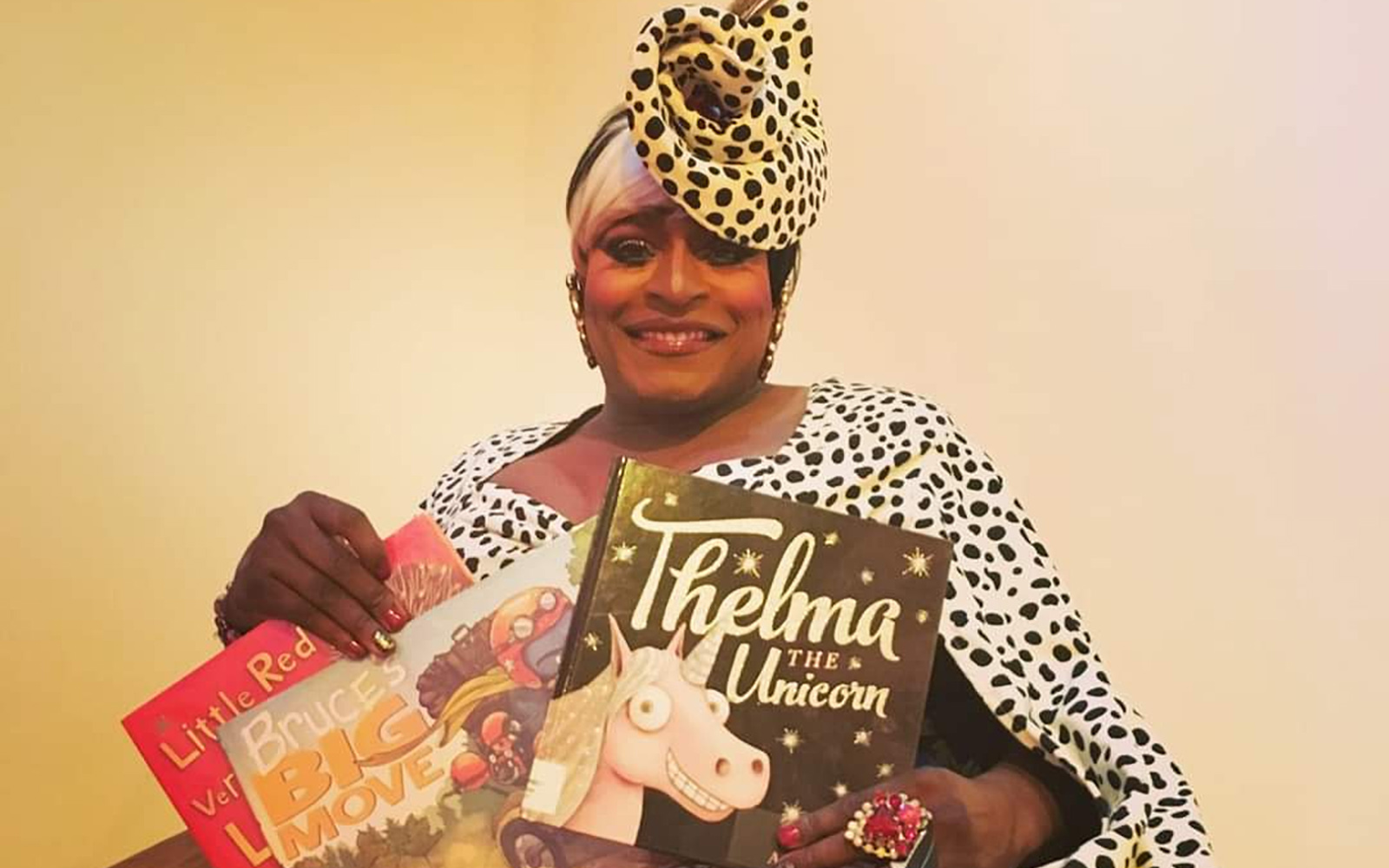

Artists pull influence from everywhere—and heritage artists can build community around anything. The subject of this month’s Heritage Highlights is Akasha Van Cartier, the Last Lady of Pittsburgh, an accomplished drag queen with twenty-one years of experience. Originally from Canfield, Ohio, she has performed all over Pittsburgh, including at the Warhol Museum and the Carnegie Library as part of her Drag Queen Story Hour program. Rivers of Steel’s Jon Engel spoke to Ms. Van Cartier about her personal history with drag, her many inspirations, and the ways this community operates through performance.

I came into my own.

How did you first get started in drag?

My first show was at a Youngstown State AIDS benefit. I was one of the last minute throw-ins, because of an accident that had happened. It was my first time experiencing drag, but I realized how much of a difference I could make and how much I could give back to the community.

Interesting. So you were a last minute throw-in, how did you get involved in that show?

I had done some choreography for some of the queens in the show, and I also knew some of the make-up artists. One of the queens had gotten hurt and I knew what was going on, so it was the decision of the casting director that I was going to take her place. I was originally going to school for music education and dance performance, so I think I was going to school to eventually be a drag queen.

Do you remember the first time you would have heard of drag?

The first time I heard of drag, I was around 14 or 15 years old. I started venturing out because I had discovered who I was at a very young age, so I ventured out into finding out more about things. It wasn’t like you could go to a library or, y’know, go online and go to a hookup site or stuff like that, you had to actually know someone and explore situations. And I found a bar that I started going to in Youngstown, Ohio at an absurdly young age-

(laughs)

Because it was in Youngstown, Ohio, it was a frightening experience. But at the same time, it was one of the most relieving and enlightening experiences to realize you’re not alone, there’s an entire community of people out here that are just like you and support you in everything that you do. You just had to find them, and not a lot of people have that opportunity.

Moving to Pittsburgh was… it was my Queer As Folk moment. When I originally moved here, I thought, y’know, I was moving into the life. I didn’t know that it was going to be not Queer As Folk. [Editor’s note: Set in Pittsburgh, Queer as Folk was a Showtime drama that revolved around a group of gay friends. It ran from 2000 to 2005.] Which—I was surprised, but I was pleasantly surprised because, you realize, after a certain point of time, you weren’t ready for Queer As Folk after coming out of Youngstown, Ohio. And I feel like Pittsburgh was that next step up, coming from a very small town to very small town ways in a larger city setting.

After that first show, how did your career develop?

After that show, it was a very quick progression. Because of the money that we had made, I had turned up on the front page of the city newspaper the next day, which was a Sunday—which my parents noticed while they were getting ready for church.

Ahh.

So that was a situation. But things progressed pretty far and fast from there, because it was like, who can say what? You’re now open and you’re out and you’re living your truth and your freedom. People can say what they want but that doesn’t take away from who you are and what you do. I just sorta’ came into my own and realized, everyone’s not going to accept everything, but if you do it and you believe in it… you do you and let them do them.

The queens in my family, we’re not just queens.

Are there any other institutions or specific mentors who you learned a lot about drag from?

I was very much a drag orphan. And I think that was sort of by choice, but sort of because I was a ruthless child and I had a really bad attitude. So a lot of people didn’t know how to take me, because my truth was mine and I needed to force it upon everyone else. Which I realize now, that’s not the case. That’s my truth and no one else needs to understand it or deal with it.

But there were significant people who very much affected my drag. I would say, from the Ohio scene, there were queens like Linda Lacee, who would then eventually be in the Pittsburgh scene. And now she’s a male performer in the Ohio and Pittsburgh scene, so she has experience in performing and theater. Samantha Styles was the first ever queen to paint my face and introduce me into what glamor in drag was. I had inspirations like Maxine Factor and Aaron Steel! They were people who taught me how to perform and how drag isn’t just dancing on stage in women’s clothing, it’s musical theater. It’s a part of acting. It’s being a smaller part of the entertainment industry, just on a local level.

When I moved to Pittsburgh, I sort of floated around. I got a feel for things in different families, who taught me different make-up techniques, different bodying techniques. I’m the USA of drag – it’s just a melting pot of knowledge that’s been gained to make me a better person.

You described yourself as kind of a “ruthless child”—I wonder, how does that effect the way you interact with younger queens? Do you try to be a mentor to them?

I do have an extensive family tree of queens underneath me that I’ve taken in as my children. And I do encourage drag on many levels. But at the same time, I am that cautious person who believes that your outside life influences your drag life. So if you don’t have that together, then your time in drag is not now. Because that’s going to affect your performance quality, what you bring to the stage, and what people see. Those feelings in our actual life do come across in our performances and what we do as entertainers.

The queens in my family, we’re not just queens. We’re people that have gone on to be nurses and people who are still in school to get engineering degrees. I believe in investing as much time into their drag as into their male lives, because, at the end of the day, it’s the boy behind the mask that’s making it all happen.

Can you describe a little bit what you mean by families?

A drag family is a chosen family that you find that inspires you to do better than you thought that you could do, that instills the factors and the morals of what you can be and have the ability to be over what people expect you to be. They’re the people who have your back when you feel as if blood family has turned against you or you have nowhere else to or you can’t talk to someone else about this situation. They’re that backbone that you can lean on. Any problem, big or small, male or drag, we can handle, because we’re a solid unit that works together.

Before the entire, like, pandemic, I used to try to have, at least once every two weeks, a family dinner. It would be a barbeque or just a large dinner where we all just got together and talked about what was going on in our lives, had a good time, y’know, enjoyed each other’s company. That way, we knew we were still on the same level. If there were any problems, we talked those problems out. Someone wore bad hair? We talk that out. We talk about them. If we talk about you, we care about you. If we’re not talking about you, that’s when you should be worried.

I sort of felt like a local superstar…

Pivoting subject matter a little bit, what about drag appeals to you? What makes you want to do drag?

Drag appeals to me, in general, because I went to school to dance and sing and do music, to be on Broadway. And drag was like that next step down from being famous. Because everyone wants to audition for that part and everyone wants to do that, but only so many people want to do that local aspect. I sort of felt like a local superstar, and that was amazing to me! It was a way to step out of the homeliness and homebody of who I usually am into something much greater.

What communities would you say you perform for? And how does your performance engage that community?

Recently, there’s been not much community to perform for, because of the pandemic. But I’ve performed for many communities because I’ve done many local bingos and brunches, which caters to more of a heterosexual sort of crowd. I’ve done Drag Queen Story Hour for multiple years, which caters to infants to 13, 14 year olds. And then I’ve also performed in the bar scenes, which caters to our college scene to 35…so I’ve catered to infants to ninety-nine playing bingo and above.

I’d like to believe I give an overall sort of wholesome drag that can be accepted anywhere, as entertainment and as theater.

The consistent interest that I think I’m hearing is the desire to do a theatrical performance, would that be right?

Yes, because, when you think about musical theater, when you think about Broadway—that’s what we want to bring to the stage. That Broadway, “we can’t take our eyes off of you” because—are you singing? Are you not singing? Is your costume appropriate to what you’re supposed to be giving? Is your hair swept the right way? When the music comes in proper, does the fan blow your outfit and hair properly? All the production! And if you produce that properly, it can change the entire aspect of what you’re trying to portray.

That’s really interesting to me because, I’m used to thinking about drag as, like, make-up and wardrobe and, y’know, personal kind of stature—

I think of drag from a pageant aspect and, when I think pageantry, I think they give you that large stage for a reason. Stages are meant for Broadway and grand productions, so why wouldn’t you utilize that to the maximum potential? To where people are going to talk about you for years and years to come?

In order to see a better future, for the future of drag, the future of the people around me… I have to change what I’m doing and how I’m doing it.

So you mentioned Drag Queen Story Hour – could you describe it a little bit?

Drag Queen Story Hour is a program where we are drag queens for education. We read stories to children, and adults. We have interactive games, interactive songs, puzzles. We provide an interpreter for sign language as often as possible. It is basically a program to stimulate the children into learning and paying attention to what we’re saying. At the same time, it teaches the adults different ways that they can implement these things at home in order to grasp their children’s attention. To teach them [the children], at an earlier age, how to deal with different aspects of life that they generally wouldn’t be able to experience on an everyday basis.

The program came from queens in New York, who started it, and it just branched out from there. Because there were a lot of queens who didn’t just want to be seen as RuPaul’s Drag Race show queens. They didn’t wanna be seen as just entertainers in the nightlife scene, but they wanted to bring drag into the mainstream and show, we’re not something to be feared. We’re no different than a clown at a birthday party, a dragon at a birthday party. This is just the chosen “princess”, or theme, that we’ve been asked to provide.

I wonder if you could talk a little about why you think it’s important or valuable to expose children to drag, specifically?

Being that I grew up in a religious situation and I was able to branch out and find myself from there, I was told at one point in time that it was sad to take children to Pride because that’s “brainwashing” them. Yet, at the same time, people take their child to church every week, all year long, and they find that as “teaching” them. But it’s not on the same level. So, when I look at it, I think the children need to learn there are differences, there are people out there who are not exactly like you.

They need to be educated, that way they can properly respond to the situations in life that are going to be around them. We need to learn about each other’s diversities and differences, struggles and pains that we’ve gone through to become who we are, because that’s the only way, at any point in time, that we’re all going to be on an equal level of taking care of each other.

I think that’s a really good answer—

That really sounded like a pageant answer.

(laughs) It did! But that’s not a bad thing!

I have a niece- well, she’s like my goddaughter. She was looking at someone in a magazine and said, “Mommy, why is that boy wearing a dress?” And [her mother] said, “Well, Auntie Kasha does, and what’s wrong with that? What’s the difference?” And she said, “Auntie Kasha wears the big eyelashes!”

She’s only five years old, and she realizes, and she asks questions. Her mother is open enough to sit down and explain to her, and be like “OK, so, Auntie Kasha’s a little different.” I remember when, the first time my goddaughter came over to my house and I was there as a boy. She said, “Are you Auntie Kasha? ‘Cause you like Auntie Kasha”. We tried to convince her I was Auntie Kasha’s brother, it did not work.

(laughs)

And ever since then, she’s accepted it. She’s just like “Hey, that’s Auntie Kasha, she’s different sometimes, but I like Auntie Kasha.” It doesn’t mean as much to the children as it does to the adults. And it’s all about what the adults are showing the children. They’re following the lead of the people they are being raised by. I think that, in order to raise a better generation, we have to be better people. And that’s what I try to do!

I know I had my rough years in drag, and I definitely had my troubled years in drag, where I was a terror and people were afraid of me and I had an attitude, but I learned! In order to see a better future, for the future of drag, the future of the people around me, well then, I have to change what I’m doing and how I’m doing it.

That’s when I started reading to children and getting my life together. And I can say it’s one of the best things I’ve ever done.

Everything stems from that first brick that Marsha threw!

I want to talk a little about the history of drag. Specifically, I wanted to ask, what communities did drag develop from? And why might those communities have developed drag?

I would have to say that, for me, the drag community comes a lot from the melding of musical theater, drama, a lot of the ballroom, and vogue scene… I don’t even know if I’m allowed to say this, but, for me, drag comes from Black culture. It comes from a point of having to hide your identity in order to expose who you really were. It comes from a factor of being appreciated for what you do and not how you do it, because…

There’s 170-plus white queens, and there’s 15 Black queens, and it becomes one of those points of, are you being bumped to be that token Black queen for this show? Because I’ve noticed, ever since the Black Lives Matter movement happened, my requests have gone up, as well as my daughters’. Because people started complaining, if you don’t have one Black queen in this show, that’s of color, we’ll boycott your show. And that’s not why we want to be booked. That’s not why we want to be acknowledged.

There’s always a battle and a struggle, and it’s always in the forefront, but it’s in the background of people’s minds. There’s that struggle in the factor of being seen but not seen.

At the same time, the dancing and the entertainment factor, and the dramatics of voguing and expression that’s inside of that dance also influences and brings out an entirely different flavor to drag that’s celebrated through all cultures of drag. From iconic moves like death drops and, y’know, the girls throwing themselves on the floors, and dips and spins—these are things that would not exist, were it not from the adventurous factor of the voguers, who were Black and Latino queens.

So, for me, a lot of it is a cultural representation in an art form that I feel we brought to life that was taken over and manipulated by white people, as many other things have been. And that’s really the nicest way it can be said.

Across both queer and Black histories, what function has drag played in the lives of queens, both historically and now?

Well, you could it take from the standpoint of the Stonewall riots. They were the first ones to throw those bricks, stand up and say “we’re not gonna take this anymore, there needs to be a change and if violence is the way to make that change, or realize that that change needs to be made, then that’s where we’re going”. I believe that, literally, everything stems from that first brick that Marsha threw! [Editor’s note: Marsha P. Johnson was a Black activist and drag queen from New York City who participated in the Stonewall riots and, according to some accounts, started them.]

When you think about where drag has come from then, it’s strayed a lot from the path of the activism and the standing up for the community that it should be, into pettiness between queens. And as an older queen, it sort of makes me back off the scene, because it’s not the reason that I got into the game and what I want to see continue to prosper.

They want a show and I’m here to give you a show.

We’ve talked a lot about history at this point. How do you think drag might change over future generations? How do you see it evolving?

I don’t feel that drag will ever stop evolving. It’s for everyone, it’s by everyone, regardless of age or gender. Get up, dress up, have fun. No one can tell you what your drag is, no one call tell you what your drag isn’t, no one can say that your drag is invalid or not worth being drag, because there’s always one fan for everyone out there.

So I think that there’s no limit for where drag is going to expand to or where it’s going to go. I just know for a fact that history repeats itself, so the girls better get ready for that new wave of old school drag. Because us old girls are coming back!

(laughs) I think that’s really promising. What do you feel is the most interesting, or satisfying, part of doing drag to you?

For me, I’d have to say, it’s literally the joy that it gives people. They’ve come here to have a good time. When you can see them, and their eyes light up while you’re on stage, and they’re just soaking up every movement and every word that you give, you know that they’re thinking of nothing else except for the fun that we’re having right here, together. I see that in the eyes of the children when I read to them and we sing songs and play. I see it in the eyes of the people at bingo! They want a show and I’m here to give you a show.

What do you think is the best performance that you’ve ever put on?

(sighs) The best performance that I’ve ever put on? Wow.

I would have to say, my proudest performance—I’m not sure if it was the best performance I’ve ever put on!— but the year I won Miss Pittsburgh. I did a dominatrix performance, but it was a complete dance and spoof number. And I won Miss Pittsburgh, which was the biggest title that you could achieve in Pittsburgh, and I was only 18 years old.

So I had to just come into the scene, and I took the biggest pageant that I could, and it was the greatest moment for me, because I realized I had made it. But that takes you back to that local celebrity. I felt like I was the Michelle Obama of Pittsburgh.

It was an amazing moment and a confirming moment that, maybe you are doing something right and maybe you are making a difference. And now, here we are, y’know, a good 18 years later than that, and I feel like I have made a difference.

Read more in the Heritage Highlights series. Check out this interview with Turkish Calligrapher Benjamin Aysan.