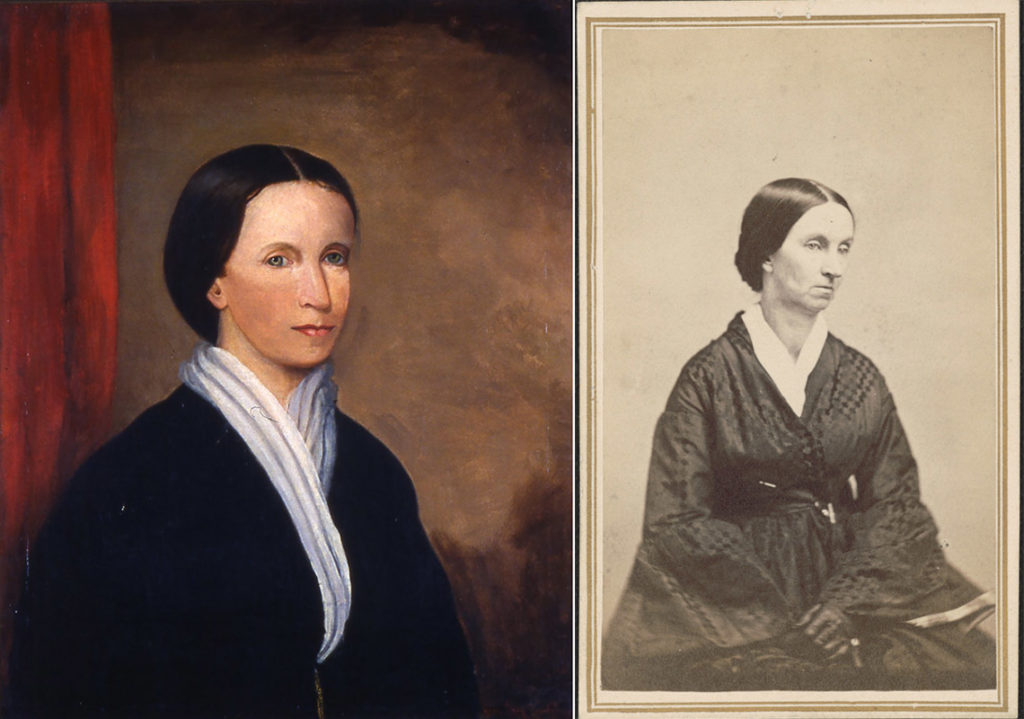

A detail Jane Grey Swisshelm’s Self-Portrait, circa 1840-1845 / Senator John Heinz History Center, Courtesy of N.N. Moore.

Jane Grey Cannon Swisshelm’s Autobiography, Half a Century

A Literary Look is a recent series that features recommended reads from the Rivers of Steel. For Women’s History Month, Dr. Kirsten L. Paine, our site management coordinator and interpretive specialist, reflects on one of her favorite historic Pittsburghers—Jane Grey Cannon Swisshelm. Working as a reporter, newspaper publisher, women’s rights advocate, and abolitionist throughout the nineteenth century, Swisshelm was a woman ahead of her time. Using her autobiography as a starting point, Dr. Paine leans on her own expertise in literature from that era to provide context for understanding this pioneering woman.

A Literary Look is a recent series that features recommended reads from the Rivers of Steel. For Women’s History Month, Dr. Kirsten L. Paine, our site management coordinator and interpretive specialist, reflects on one of her favorite historic Pittsburghers—Jane Grey Cannon Swisshelm. Working as a reporter, newspaper publisher, women’s rights advocate, and abolitionist throughout the nineteenth century, Swisshelm was a woman ahead of her time. Using her autobiography as a starting point, Dr. Paine leans on her own expertise in literature from that era to provide context for understanding this pioneering woman.

By Dr. Kirsten L. Paine

Tucked behind and rolling away from the Carrie Blast Furnaces National Historic Landmark is land that once belonged to somewhat of a Pittsburgh legend: Jane Swisshelm. Some locals might hear her name and recall the blue historical marker near the corner of Braddock and Greendale Avenues in Edgewood. Other folks might know a bit about the newspapers she ran, or that she is credited as the first woman reporter to sit in the senate press gallery in Washington, D.C. Perhaps others are aware that she advocated for women’s rights.

Jane Swisshelm’s life drifts in and out of public knowledge, and the legacy she left behind is complicated and filled with interesting contradictions. We will explore the ins and outs of her complexities in a companion piece to this article later this month. But for now, let us take a look at a fascinating piece of writing: Swisshelm’s autobiography. Half a Century was first published in 1880, and in it, Swisshelm sets out to tell the story of her early life.

Two portraits, about twenty years apart. Left: Self-Portrait, Jane Grey Swisshelm, 1840-1845 / Senator John Heinz History Center, Courtesy of N.N. Moore. Right: Jane Grey Cannon Swisshelm, journalist, activist, and Civil War nurse, Joel E. Whitney, photographer / Whitney’s Gallery, St. Paul. United States, ca. 1865. Courtesy of the Library of Congress.

Swisshelm’s narrative voice is engaging and witty. It is sharp, idiosyncratic, and can feel personable. Readers who enjoy memoirs, biographies, autoethnographies, and other forms of life writing might enjoy delving into this volume to get to know this interesting life of local lore. History buffs might enjoy the personal perspective on a galvanizing time in the American women’s rights movement, Civil War nursing, and Pittsburgh’s urban growth. There are many ways to read Half a Century. As March is Women’s History Month, consider reading it to understand what it means for a woman born in 1815 to tell her own story, in her own voice, and on her own terms in the nineteenth century.

Most people who know me know I am a scholar who specializes in American literary culture between 1790 and 1900 with a particular focus on women’s life writing from that time period. I love spending time with stories by and about women who challenge a world that is often inhospitable to their aspirations and ideas. Nineteenth-century women’s life writing has certain hallmarks. The writing can feel intensely personal even though the writer may not reveal much. Writers blur boundaries between public and private spaces and frequently indulge public scrutiny that might come with it. I enjoy investigating the purposes and limitations of this genre of literature.

So when I use the term “life writing,” I am taking it from two sources. In her 1992 book, American Women’s Autobiography, Margo Culley considers the term “autobiography” as three parts: “auto (self) / bio (life) / graphy (writing).” Then I combine that with James Olney’s perspective on the expansiveness of what “autobiography” can be. Life writing is autobiography, but it is also memoirs, journals, correspondence, scrapbooks, and other forms of composing the self.

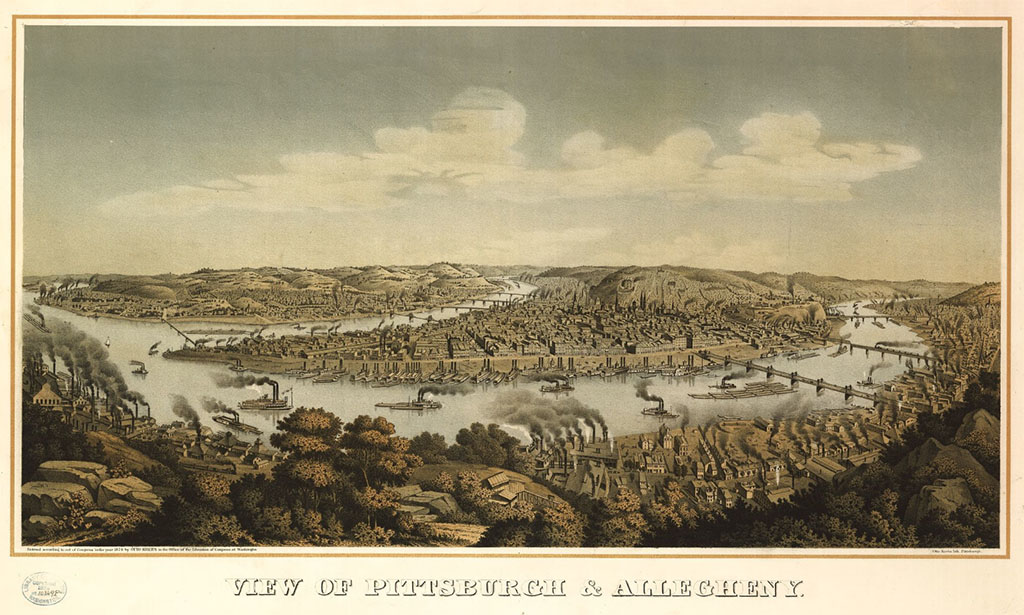

Life writing is also intensely literary. Half a Century is a wonderful example of how a middle-class white woman in the nineteenth century uses rich simile, metaphor, and symbolism to make sense of the world in which she lives. She also has a strong sense of place. For example, she writes about her birth: “I was born on the 6th of December, 1815, in Pittsburg, on the bank of the Monongahela, near its confluence with the Allegheny” (10). In 2022, the building is long demolished, but it is still possible to trace the pathways of Swisshelm’s life in Pittsburgh by following her from the burgeoning little city out to the fresh air of Wilkinsburg and Braddock, then down the Ohio River to Cincinnati and Louisville, Kentucky. For the majority of her life, Jane Swisshelm did not stray far from one of the rivers that could, and would, eventually bring her back to Pittsburgh.

Pittsburgh during Jane Swisshelm’s era. View of Pittsburgh & Allegheny, Otto Krebs, Lithogrpaher. Pittsburgh Pennsylvania United States, ca. 1874. / Courtesy of the Library of Congress.

In Pittsburgh and everywhere else in the United States, the church played a critical role in people’s lives, no matter the denomination. Publicly accounting for one’s own spiritual journey is a key feature in autobiographies like Swisshelm’s. It is typical, then, for a writer like Swisshelm to lean heavily on religion as the lens through which she considers her life. She makes her spiritual journey central to how she understands her place in the world and why that place might not be enough for her. She was born to Covenantor parents, and the strict adherence to God’s authority over one’s every thought and action meant that Swisshelm had few opportunities to question or challenge that authority.

Early in her autobiography, Swisshelm writes about memorizing prayers and Bible verses at three years old, and alongside remembering preachers, sermons, and any religious education, she also writes about ghosts and cemeteries. At the beginning of one story Swisshelm recalls, “Grandmother took me sometimes to walk in these graveyards at night, and there talked to me about God and heaven and the angels” (15). Odd, yes? However, given the context of the early nineteenth century and the closeness people had with death, the graveyard is an ideal teaching tool for discussing mortality and the divine afterlife. Swisshelm muses, “I was sufficiently interested in these, but especially longed to see the ghost, and often went to look for them,” and sometimes she “went home to lie and brood over the unreliable nature of ghosts” (15). Her interests lie not solely in the dutiful contemplation of heaven and hell. She documents the fleeting, unprovable, weird parts of spiritual existence that, perhaps, cannot be learned by following all of the rules.

Swisshelm builds resistance to, and rejection of, authority throughout her narrative. It culminates in her methodical dismantling of marriage as an institution designed to subjugate her. The first chapter devoted to her doomed marriage to James Swisshelm is entitled, “Deliverer of the Dark Night.” In it, Swisshelm unleashes all of the ghosts that would continue to haunt her through her life. She writes about how “he had elected me as his wife some years before this evening, and had not kept it secret” (40). James Swisshelm pursued her for years, and by the acknowledgement of both her family and his, “he had been assured his choice was presumptuous, but came and took possession of his prospective property with the air of a man who understood his business” (40). Words like “possession,” “property,” and “business” highlight the transactional nature of marriage and her value as an object for sale. Small details like this lay a foundation for how she navigates the issues of women’s rights to property, to children, and to divorce, for the rest of her life.

In the nineteenth century, belief that women belonged at home regulated daily life for most people. Women largely relegated their influence to raising children and tending to domestic responsibilities. Laws barred women from voting and holding political office, and they were mostly prevented from pursuing higher education, training in professions, and owning businesses and property. In many ways, women were property, so there were very few opportunities to hold positions of public authority. However, Swisshelm rejects the expectations of the “woman’s sphere,” precisely because she cannot think of a woman who succeeded in escaping it. She “had never then heard the words, for no woman had gotten out of it, to be hounded back” (48). As so much of the narrative chronicles her journalism career and the public platforms she created in order to speak about issues that mattered to her, it is interesting to read about how she “had gotten out of it” and refused in every way imaginable “to be hounded back” (48).

The Civil War created many opportunities for women to leave their designated sphere. Jane Swisshelm was one of the hundreds of women who, through the United States Sanitary Commission and under the leadership of other women like Dorothea Dix and Clara Barton, nursed soldiers in ramshackle hospitals near every battlefield. This portion of Half a Century is of especial interest to me primarily because it is about Swisshelm’s service during the Civil War, but I also think it is a fascinating look at how a seasoned journalist tries to assemble fragments of memories that are all part of a great national trauma. Memoirs of female Civil War nurses abound, and Swisshelm fits hers well within the somewhat self-denying style and tradition of women writing about their service. On the surface of such narratives, a woman’s motivation is motherly devotion to the wounded nation. However, once a reader pushes beyond Swisshelm’s public assurance that she behaved herself and completed her duties without losing an ounce of femininity, they will start to see Swisshelm, yet again, pushing against the boundaries of an institution designed to slot her into a specific role.

She argued with Dorothea Dix over the “kind of women” who should be allowed to train as nurses and threatened to “apply to my friends Mrs. Abraham Lincoln and Secretary Stanton, and have your authority tested” (302). She recounts the horrors she witnessed in the aftermath of the battle of Fredericksburg. She cajoled doctors into pursuing better treatments, conversed with sick and dying soldiers as they looked to her as a refuge, and, by her own account in a chapter called “The Old Theater,” almost single-handedly saved an abandoned group of soldiers and cowering nurses (308–314). These chapters comprise most of the last third of the book and piece together Swisshelm’s movement from hospital to hospital.

Part of Swisshelm’s narrative provides the basis from which she discovers, and then defines, the parameters of her belief in abolition, which was, of course, the primary cause of the Civil War. It is important to remember that, as a white woman in the nineteenth century, Swisshelm’s ability to synthesize and discuss the institution of slavery is limited to the language available to her at the time. It is also important to remember that how she frames her belief in and work with abolitionist groups is always in relation to those with whom she speaks on a regular basis. Of course, that means the language she uses to discuss the institution of slavery is shockingly racist to contemporary audiences.

Language in nineteenth-century autobiography challenges modern readers precisely because it puts present-day understandings of how and why words and phrases are weaponized to hurt people over top of archaic models of storytelling. However, with Swisshelm’s narrative as an example, readers can consider how she commands a gut-level emotional response by cultivating sympathy. She does not sweep violence away to make it more palatable for people. Rather, the violence embedded in her language and in her descriptions of violent acts are there to provoke anger, outrage, and even perhaps a little disbelief. After all, she writes about her first encounters with enslaved people while trying to reckon with the haunting scenes of violence that seemingly called her to action.

Those moments in her autobiography are bitter and deeply unpleasant, even as those same moments help readers understand how nineteenth-century people lived and wrote about their society, environments, and experiences—but proceed with caution.

Photographer’s note: “This is one of four small, hard-to-spot stone reliefs built into a brick wall in the Coffee Way alley downtown, c. 1865. The artist is unknown. Exactly whom this relief represents is not recorded; it is speculated that it Mary Croghan Schlenley, a noted Pittsburgh philanthropist of the day; or Jane Grey Swisshelm, an American journalist and abolitionist.” One of dozens of examples of exemplary public art and architecture, some old, some new, in the venerable “Steel City” of Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. Pittsburgh, 2019. Carol M. Highsmith, photographer. Courtesy of the Library of Congress.

Of course, Half a Century delves into Jane Swisshelm’s journalism career. She details every paper she ever started, discusses in detail her approach to reporting and editing, and wields the power of the press to advocate for sweeping political, social, and economic advancements for marginalized groups of people. Readers who know Swisshelm’s extensive body of work in this arena will not be disappointed by the stories she tells.

I plan to use this part of the book as a pivot point for a companion piece about Swisshelm’s activism via the press. While it might reference Half a Century, the next piece on Jane Swisshelm will not be about her autobiography. It is a deeper dive into her journalism career as it relates to causes that eventually impact labor in the late nineteenth century.

Physical copies of Half a Century might be difficult to find because it is out of print, but it is easy to access online. Search for the book title and author on archive.org and enjoy one of the high-quality digitized copies located there.

Bibliography

Culley, Margo. American Women’s Autobiography: Fea(s)ts of Memory. University of Wisconsin Press, 1992.

Olney, James. Memory and Narrative: The Weave of Life-Writing. University of Chicago Press, 1998.

Swisshelm, Jane. Half a Century. Jansen, McClurg & Company, 1880.

Image Credits

In order of appearance:

Swisshelm, Jane Grey, painter. Self-Portrait. Ca. 1840 – 1845, painting. / Senator John Heinz History Center, courtesy of N.N. Moore.

Whitney, Joel E, photographer. Jane Grey Cannon Swisshelm, journalist, activist, and Civil War nurse / Whitney’s Gallery, St. Paul. United States, ca. 1865. [St. Paul, Minnesota: Whitney’s Gallery] Photograph. Courtesy of the Library of Congress.

Krebs, Otto, Lithographer. View of Pittsburgh & Allegheny / Otto Krebs lith., Pittsburgh. Pittsburgh Pennsylvania United States, ca. 1874. Photograph. Courtesy of the Library of Congress.

Highsmith, Carol M, photographer. One of dozens of examples of exemplary public art and architecture, some old, some new, in the venerable “Steel City” of Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. Pittsburgh Pennsylvania Allegheny County United States, 2019. -07-05. Photograph. Courtesy of the Library of Congress.

Enjoy Dr. Kirsten L. Paine’s article? Read another story from the A Literary Look series.