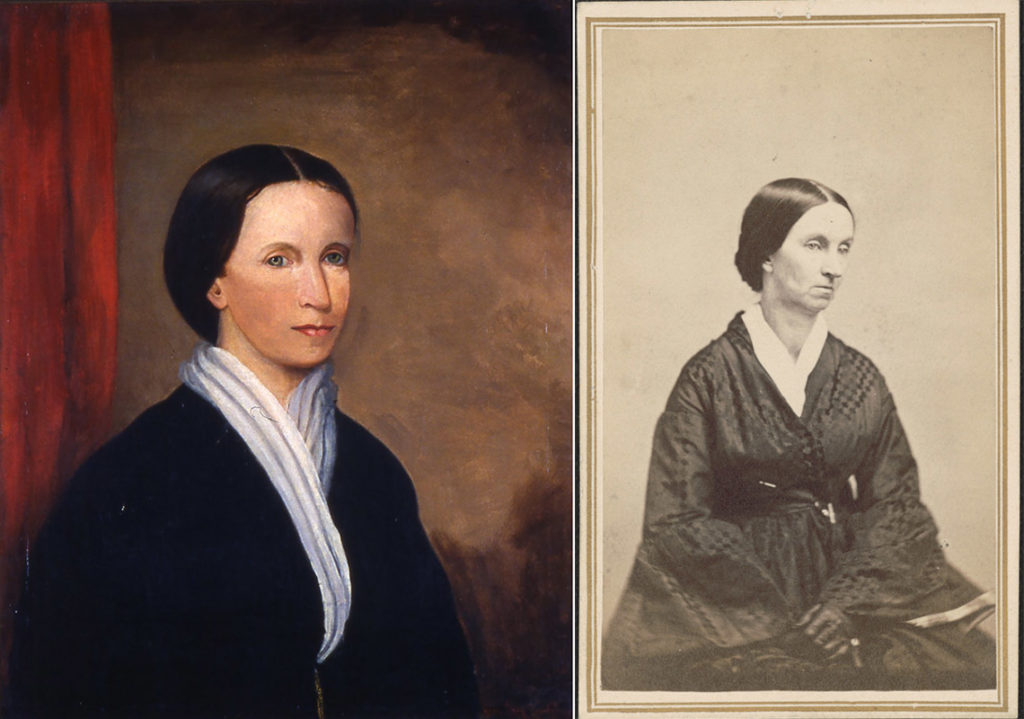

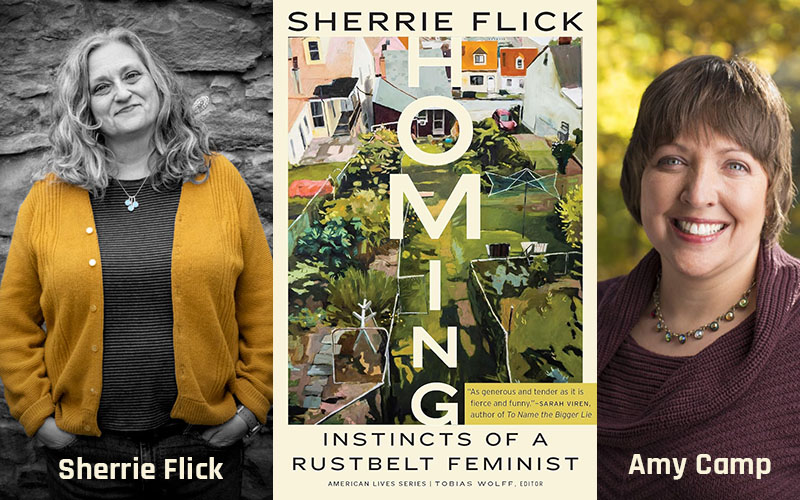

Join writer Sherrie Flick, pictured above, for a conversation about her new book Homing: Instincts of a Rustbelt Feminist that explores a sense of place in southwestern Pennsylvania. Photo courtesy of Sherrie Flick.

Homing—Exploring a Sense of Place in Southwestern Pennsylvania

On Thursday, October 24, Rivers of Steel will host writer Sherrie Flick at the Pump House for a conversation that explores her journey away from—and back to—southwestern Pennsylvania.

Her latest publication, Homing: Instincts of a Rustbelt Feminist, is a collection of autobiographical essays that traces her journey from her hometown of Beaver Falls to her cultivated home on the South Side Slopes, with time spent living on the East Coast, West Coast, and a significant stop in between. While reflecting on the experiences that shaped her, Flick offers insights on culture, characters, and place—with a special emphasis on the fabric of southwestern Pennsylvania.

Guiding the conversation with Flick is Amy Camp, who as a trails and tourism consultant is a woman who knows how to explore a sense of place. Also an author and fellow Beaver County native, Camp describes herself as having come up “a town and a decade apart” from Flick. From the boom and bust of a steel town adolescence to the vibrant communities these women help to shape today, Rivers of Steel explores perspectives of life in the Rust Belt.

In anticipation of this event, Lynne Squilla chatted with both women to learn a bit more about what to expect.

By Lynne Squilla, Contributing Writer

Sherrie Flick and Amy Camp will reflect on a sense of place as reference in Sherrie’s book Homing: Instincts of a Rustbelt Feminist.

Considering How Place Shapes Us

What does it mean to have a sense of place? Rivers of Steel invites two dynamic female authors and creators to delve into this multilayered subject that plays into all of our lives.

Writer Sherrie Flick has visited and lived in many places, from her birthplace in the former mill town of Beaver Falls, Pennsylvania, to her current garden-terraced home on Pittsburgh’s South Side Slopes, with much time spent on the East and West Coasts and points in between. She questioned why she wanted so desperately to leave home and to travel, and why it is that she ultimately returned to this Rust Belt roost. The result is a collection of autobiographical essays in her new book, Homing: Instincts of a Rustbelt Feminist.

“I wanted to examine how memory works, to think about the ways in which memory connects to history and to lived experience. Some of the essays in the collection circle around questions and ideas about what it means to leave and what it means to stay in a place you don’t fully understand.”

Flick is the featured author for Rivers of Steel’s evening of conversation at the Pump House on October 24: Homing—Exploring a Sense of Place In Southwestern Pennsylvania. She will read from her essays, which explore how place has shaped her sensibilities as a writer, feminist, educator, and human being, with a special focus on the strange and wonderful area that is Pittsburgh and southwestern Pennsylvania.

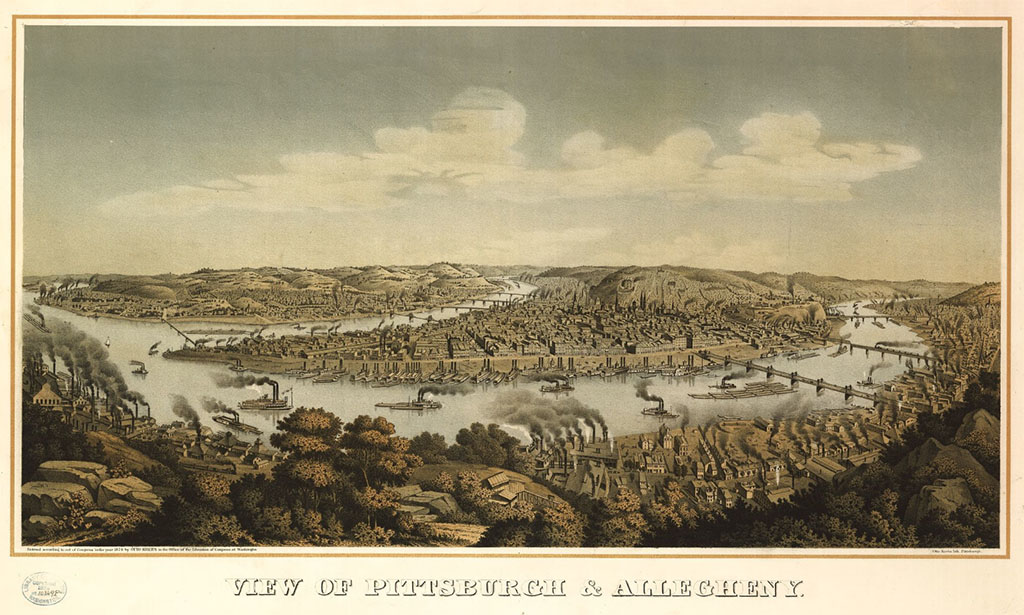

“Southwestern Pennsylvania can be hard to understand, even if you’ve lived here a while. There is something here that draws people in; it’s that quality of the unknown. The idea of a mystery. There are the common tropes of sports town, mills, and labor, of course. But there is more to this place.”

Flick’s essays delve into these other elements, weaving stories that touch on intriguingly diverse topics such as faith, whiskey, grief, eight ball, and gardening, as well as Andy Warhol, the poet Peter Oresick, her father, and her older brother’s telltale dialect. Flick noted that place has a big impact on each of us, whether or not we are fully aware of it, whether we leave or stay.

“Warhol is a great example of someone who grew up here, sucked in a bunch of ideas and influences, and left to New York to make it big. He didn’t come back here until he died,” she notes wryly.

Amy Camp, author, trails consultant, and fellow Beaver County native, will guide the conversation with Sherrie Flick. Photo courtesy of Amy Camp.

Factoring in Culture, Heritage, and Nature

Guiding the Pump House conversation with Flick will be Amy Camp, an author herself and a trails and tourism consultant whose career has focused on sense of place. As founder of Cycle Forward, Camp was instrumental in launching the nationally recognized Trail Town Program® in 2007. She works with local leaders and communities to create a more robust outdoor recreation economy in areas hit by industrial collapse. She initially settled in Pittsburgh in 1999 and watched as the empty steel mill sites grew into housing and retail shops.

“There was already a lot of change. It was no longer the Smoky City,” said Camp. “There were already some riverfront trails in place. In my work now, I’m often thinking of culture and heritage and what makes the area special. When you step off the trail into a community, what is that place all about?”

Nature likewise creates a sense of place. Camp likes the idea that the area’s natural surroundings—the rivers and valleys and resources that caused industry to take hold here—are “homing” back to their natural state. She spoke about recently hearing a talk about returning to returning to a nature-positive, carbon-neutral world. “We need to continue to strive to live in better harmony with nature, and this place can be that.”

Camp’s book, Deciding on Trails, gives the backstory of the Trail Town movement and outlines best practices for trail communities. When questioned why she is attracted to Pittsburgh, Camp muses, “I learned recently that my great-grandmother went right from Ellis Island to Hazelwood. So I’m asking, ‘Hmmm, did it have something to do with her? Something deeper than our conscious knowing?’”

Sherrie Flick’s home on Pittsburgh’s South Side Slopes overlooks the community below and the Oakland neighborhood across the Monongahela River. Photo courtesy of Sherrie Flick.

Choosing a Place / Staying or Going

Flick says the Pump House discussion and Q&A with Camp and her will examine the why of choosing to live in a certain place. The audience will be invited to weigh in, too.

“Amy is also from the same Beaver Falls region as me,” Flick says, “and also lives on the South Side, but is younger than me. She has very different opinions about Pittsburgh than I do. So I think we can look at generational layers there. Depending on age and how you experienced a time in history, you’ll have a different conceptual understanding of a place.”

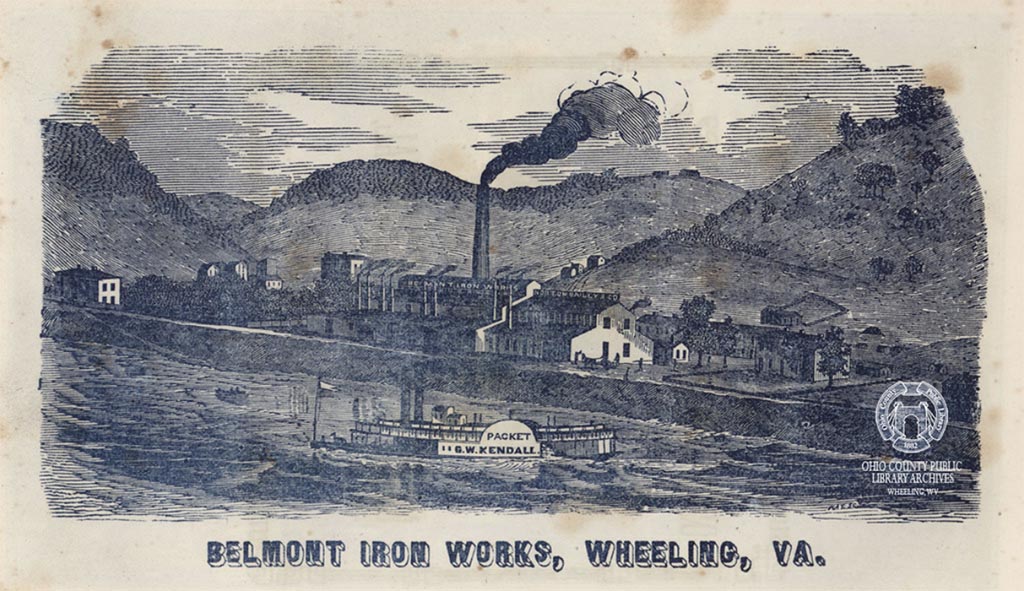

Flick’s parents chose to settle in Beaver Falls at a time when industry was booming. By the time Flick reached high school, the mills had largely shut down.

“The mill town was dying as I graduated high school. Disappearing before my eyes, because of this its history wasn’t written yet. There was no easy way to talk about the region in the mid-80s.”

“People choose ‘place’ for many reasons Flick continued. “My parents ended up in Beaver Falls to have a better life for their kids. Their decision was based in employment. I did the opposite of my parents. I knew for sure I had to leave and I knew I wanted to explore for exploring’s sake. I lived in New England, San Francisco, and Nebraska. I traveled all over the country.”

Sherrie Flick’s backyard garden, featured in the essays “Cultivation” and “Caretaker, Murderer, Undertaker,” helps define her relationship with the place where she settled. Photo courtesy of Sherrie Flick.

The Give and Take of Place

Sherrie Flick’s travels gained her degrees in English literature from the University of New Hampshire and University of Nebraska and fueled her many books and articles, which have appeared in such publications as the Wall Street Journal and New England Review. She has also garnered numerous fellowships and awards, including a 2023 Creative Development Award from The Heinz Endowments, a Golden Quill, and PA Partners in the Arts grants.

But this prodigal daughter eventually returned to postindustrial Pittsburgh, becoming more involved and aware of the character, history, and community of the area. Among her first creative endeavors from 2001 through 2010 was as co-founder and artistic director of the Gist Street Reading Series. Housed in an artist’s studio on Gist Street in Pittsburgh’s Uptown neighborhood, the freewheeling, monthly event featured local writers and poets, as well as national authors.

Flick also worked at the Frick Art & Historical Center, The Heinz History Center, and has created programming for the Carnegie Museum of Art, Silver Eye Center for Photography, and, most recently, Shiftworks, as part of their Creative Corps. Her Walk & Write programs take small groups through area neighborhoods and unlikely public spaces to observe and write. She is hoping to do one of these sessions at the Carrie Blast Furnaces National Historic Landmark. Flick is currently a lecturer at Chatham University and will serve as the 2025 Distinguished Professor of Creative Writing at Davidson College.

Flick strongly credits this once-industrial region with forging her feminist viewpoint: “I realized that my feminism was a mix of not just learning theory in a class, but also formed from the idea of labor, of effort, the strength of the body that is a focal point in mill towns.”

She continues, reflecting on her hometown of Beaver Falls: “It was a very macho place, and a person is informed by that growing up as a woman. You notice sexism that’s in your face, but sometimes you can process that to your advantage.”

After years of wandering and more than 20 years of living in Pittsburgh, Flick thinks she’s uncovered some of the draws to this region: “This is not a place that gives in to trends; sure, it’s hipper than it once was. Pittsburgh is settled-in, not pretentious, and bragging won’t get you anywhere. That’s appealing to me.”

Flick added, “You can start things here. It’s a great place for innovation . . . and historically always was. People can make their own way, try things out,” she explained. “Also, because of the hilly geography you often literally stumble on things that are surprising and fun and unusual, so you feel a constant sense of discovery.”

Two sets of Pittsburgh’s infamous steps that are referenced in Sherrie Flicks essays help to define both the physical character of the South Side Slopes and reflect its industrial heritage. Photos courtesy of Sherrie Flick.

Exploring the Postindustrial

The Carrie Blast Furnaces, the Pump House, and the Bost Building are among the kinds of unusual discoveries to be made in the Pittsburgh area. Both Flick and Camp feel a connection with Rivers of Steel when it comes to defining place and helping historic sites preserve their history and their significance for future generations: “I wish I had seen all the industry that was here, and at the same time, I’m glad that I didn’t.” Camp said. “This region experienced trauma, and it’s a natural inclination to want to wipe away all that trauma. But the fact that some of it is still standing helps tell the story of this place. I mean, what if there was no Carrie Furnace?”

One of Camp’s favorite quotes about place is from Ed McMahon of the Urban Land Institute. “He said, ‘A sense of place is that which makes our physical surroundings worth caring about.’”

To Camp, Pittsburgh and southwestern Pennsylvania’s former industrial communities have an endearing quirk factor worth preserving. Organizations like Rivers of Steel play a major part in that effort, as well as in tying nature, trails, arts, and culture to the story of labor and industry in the region.

“Part of our charge as a National Heritage Area is to engage in storytelling that helps explore and define a sense of place,” said Carly McCoy, director of communications for Rivers of Steel. “We do this throughout all of our programming and the content we share, but our conversation with Sherrie and Amy is an exciting opportunity to really dig in on the topic . . . to have an exchange about what it means to be from southwestern Pennsylvania and even how that varies from person to person. I’m really looking forward to it!”

Like Camp, Flick appreciates this Rust Belt region for its natural features. For the past 20 years, Flick has been happy in her “place,” hiding high atop a hillside in the South Side Slopes, with her many flower and vegetable gardens. “I am addicted to the view. The vista. It makes my world so much bigger to see the whole city before me. But the garden is what grounded me in this place and made me stay here—the organic versus the old industrial.”

Camp sums it up: “This talk at the Pump House is a great opportunity to explore Sherrie’s relationship with the region and how this postindustrial place has informed who she is as a person. It is important to have these conversations around place.”

Sherrie Flick and Amy Camp in Conversation

There are two upcoming opportunities to join in the conversation with Sherrie Flick and Amy Camp. If you can’t make Rivers of Steel’s event on October 24, make your way to Beaver for the next event on November 9. See the details below.

Homing—Exploring a Sense of Place in Southwestern Pennsylvania

Pump House, 880 E. Waterfront Drive, Munhall PA 15120

Thursday, October 24, 2024, 6:00 – 8:00 p.m.

Presented by Rivers of Steel, this is an evening in conversation with writer Sherrie Flick, guided by trails and tourism consultant Amy Camp. From the boom and bust of a steel town adolescence to the vibrant communities these women help to shape today, Rivers of Steel explores perspectives of life in the Rust Belt. The evening will include excerpted readings from Flick, a cumulative Q&A with both women, and the opportunity to pick up a copy of Homing: Instincts of a Rustbelt Feminist.

Rustbelt Reflections: A Evening of Written Word & Art

The Baby Bello, 2200 9th Avenue, Beaver Falls, PA 15010

Saturday, November 9, 7:00 – 9:00 p.m.

If you are unable to attend the event at the Pump House, we recommend this opportunity to hear another conversation with Flick and Camp in Beaver Falls, which also highlights community artist Kit Miller.

Lynne Squilla is a skilled and creative storyteller. She honed her craft as a writer and producer / director of original scripts, documentaries, articles, web content, stage, and other live presentations. While her work has taken her across the globe, she’s rooted in the Mt. Washington neighborhood of Pittsburgh, and has a passion for sharing stories about our region’s past.

Check out Lynne’s most recent prior article on the Gledaj! Sketching Session at the Carrie Blast Furnaces.

Dr. Kirsten L. Paine is an educator and researcher with more than a decade of experience working in higher education. She started working for Rivers of Steel in 2017 as a tour guide at the Carrie Blast Furnaces National Historic Landmark and was inspired by the mission to preserve such a national treasure held in public trust. Kirsten is committed to the work of public humanities education in her role as Site Management Coordinator and Interpretive Specialist. By creating and facilitating public programs that make the National Heritage Area’s history come alive for the community, she believes in archival study and teaching from primary sources as vital community resources.

Dr. Kirsten L. Paine is an educator and researcher with more than a decade of experience working in higher education. She started working for Rivers of Steel in 2017 as a tour guide at the Carrie Blast Furnaces National Historic Landmark and was inspired by the mission to preserve such a national treasure held in public trust. Kirsten is committed to the work of public humanities education in her role as Site Management Coordinator and Interpretive Specialist. By creating and facilitating public programs that make the National Heritage Area’s history come alive for the community, she believes in archival study and teaching from primary sources as vital community resources.

A Literary Look is a recent series that features recommended reads from the Rivers of Steel. For Women’s History Month, Dr. Kirsten L. Paine, our site management coordinator and interpretive specialist, reflects on one of her favorite historic Pittsburghers—Jane Grey Cannon Swisshelm. Working as a reporter, newspaper publisher, women’s rights advocate, and abolitionist throughout the nineteenth century, Swisshelm was a woman ahead of her time. Using her autobiography as a starting point, Dr. Paine leans on her own expertise in literature from that era to provide context for understanding this pioneering woman.

A Literary Look is a recent series that features recommended reads from the Rivers of Steel. For Women’s History Month, Dr. Kirsten L. Paine, our site management coordinator and interpretive specialist, reflects on one of her favorite historic Pittsburghers—Jane Grey Cannon Swisshelm. Working as a reporter, newspaper publisher, women’s rights advocate, and abolitionist throughout the nineteenth century, Swisshelm was a woman ahead of her time. Using her autobiography as a starting point, Dr. Paine leans on her own expertise in literature from that era to provide context for understanding this pioneering woman.