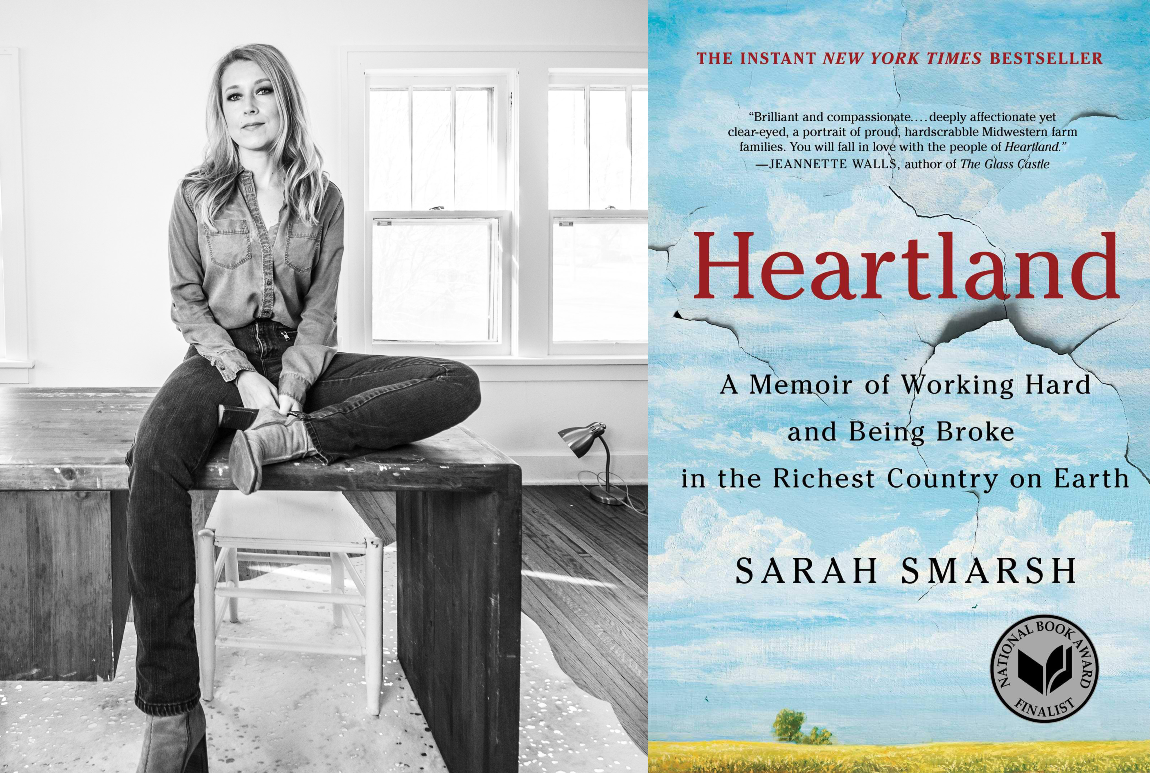

Sarah Smarsh by Paul Andrews and the cover of her memoir Heartland.

A Literary Look at Heartland: A Memoir of Working Hard and Being Broke in the Richest Country on Earth

A Literary Look is an occasional series that features recommended reads from the Rivers of Steel staff. For Women’s History Month, Dr. Kirsten L. Paine, our site management coordinator and interpretive specialist, introduces us to Heartland: A Memoir of Working Hard and Being Broke in the Richest Country on Earth by Sarah Smarsh. The One Book Community Read selection provides a foundation for discussion of working class challenges in Pittsburgh, Homestead, and neighboring communities.

By Dr. Kirsten L. Paine

This past September I had the opportunity to read Heartland: A Memoir of Working Hard and Being Broke in the Richest Country on Earth, by journalist, political commentator, and writing professor Sarah Smarsh. Her 2018 memoir was selected for the Community College of Allegheny County’s (CCAC’s) 2023 – 2024 One Book Community Read program. It is a bit of a departure from my usual fare because it is contemporary and was written by someone who is not only alive but close to my own age.

For someone who reads mostly nineteenth-century American literature written by people who are very much not alive, I was drawn by Sarah Smarsh’s deep engagement with the immediacy of her own life as a child in rural Kansas. In mapping her family’s history as farmers in flyover country, Smarsh narrates generational struggles stuck in cycles of poverty. She highlights her family as an example of the ravaged working class left behind by years of harmful public policy. While grappling with how popular social engagements consider “white trash” as celebratory, beleaguered, stereotyped, and as a lived-in identity, Smarsh treats her life and own search for identity with gentleness and works through feelings of disposability in a world where people far too often see themselves as inconsequential.

I couldn’t help but consider her experience through my own lens, growing up in rural western New York. If someone drove through town on a breezy summer day, they might find the villages and hamlets nestled in gently rolling hills rather quaint. It took twenty years and several out-of-state moves for me to understand why folks took to an environment that felt so isolating to the adolescent version of me, but now I can see some charm in the bucolic idyll despite being aware that sometimes charm is performative.

I did not understand the real conditions of rural poverty. I did not understand deprivation. I did not understand insecurity. I think I observed these experiences from a distance and tacitly understood that other people I knew had very different lives than mine. Proximity meant familiarity—perhaps a kinship—but simply living around rural poverty did not substitute for intimate knowledge of its tolls, risks, and demands on a person, family, or community.

Regardless, I left as soon as I graduated high school. Twenty years later, I find myself here in Pittsburgh, deeply immersed in historic preservation work in postindustrial communities. Our contributions to revitalization efforts throughout southwestern Pennsylvania help nurture towns and villages that, in an increasingly postindustrial twenty-first century, look a lot like the one in which I grew up.

Considering Labor

In my role at Rivers of Steel, the legacy of labor and the industrial working class are daily considerations. The throughline in Heartland that made me think the most was the way working class bodies appear on the page. Smarsh writes about women and labor as though they are one and the same—as though there can be no concept of womanhood that exists without the primary usefulness of the body as an object that can perform labor. Smarsh also handily doubles the meaning of “labor,” as it stands for the body at work and the body in childbirth. She writes, “Our bodies were born into hard labor. To people who Grandma Betty would say “never had to lift a finger,” that might sound like something to be pitied. But there was a beautiful efficacy to it—form in constant physical function with little energy left over” (Smarsh 44). And just as women’s bodies are inextricably linked to “labor,” she observes, “the person who drives a garbage truck may himself be viewed as trash. The worse danger is not the job itself but the devaluing of those who do it” (45). A laboring person inevitably becomes their task, and that in and of itself is indeed a dangerous way to think, because once a person becomes their job in that their job is their body’s primary function, they cease to appear human at all.

Later in the chapter entitled “The Body of a Poor Girl,” Smarsh writes about how “physical markers of our place and class were so normal and constant, from my vantage, that I never thought to question them: the deep, black bruises ever-present beneath my dad’s fingernails, the smoker’s rattle in Grandma Betty’s lungs, the dentures she’d had since her late twenties, the painful sunburns I sometimes got on my young corneas working outside against a hard slant of light” (82). If a body exists only as a body instead of a whole person, then the pain of intense physical labor is the world’s only indication that the body is even alive.

When I read or listen to stories of steelworkers in Pittsburgh, I hear the same refrain. There is a regional shorthand for “steelworker” to describe the bodies of men and women laboring in billowing mills. One of the tour guides, Keith Clouse, at the Carrie Blast Furnaces often talks about his own experiences as a steelworker. He tells rapt audiences his story and talks about heat exhaustion, burn scars, and the bone-deep sense that “steelworker” is an embodied identity. Working class meant working, and working was good. When someone asks Clouse if he would do it all over again, he answers, “Yes. In a heartbeat.” In some ways, I hear this sentiment echo in the way Smarsh writes, “I feel enriched rather than diminished for having lived it” (44).

Books Beyond the Classroom

When Carmen Livingston, Professor of English at the Community College of Allegheny County, asked me to represent Rivers of Steel as a community partner for the duration of the 2023 – 2024 One Book Community Read program, I jumped at the chance to engage with a modern piece of life writing. I wanted to participate for a number of reasons, but I especially wanted to see literature in action—on campus, at home, in town—as both a point of reflection and identification, and as a blueprint for the possibilities of widespread public engagement.

I sat down with Livingston to talk about her accomplishments with the program this year (as well as hopes for a new slate of projects next year), and she immediately honed in on the project’s interdisciplinarity. She said, “It’s a way for us to do American history and literature in a different way by reaching towards connections that feel real and authentic for our students. We could showcase student work through audio recordings, podcasts, oral histories, personal essays, and theatrical productions.”

I asked her why she ultimately chose Heartland as the vehicle for all of these student projects. Livingston remarked, “This was the book that spoke to the region the most. It speaks to how geography can sometimes limit you and offers possibilities for different kinds of communities to solve ongoing regional problems. Because part of what Smarsh is doing is addressing the failures of a ‘get out to survive’ mentality. What happens when you don’t want to leave . . . when you want to invest in your community? We have in this region a population that hasn’t, can’t, and doesn’t want to ‘just move on.’”

By highlighting student-centered narratives and creative writing projects in their yearlong study, Livingston’s class put Heartland in conversation with their own personal stories about classism, racism, poverty, addiction, and teen pregnancy. Livingston also wanted to ensure that her students’ work did not exist in a vacuum. Community partnerships outside of the classroom bolster the success of the Community Read initiative.

I also spoke with a frequent Rivers of Steel community partner, Emily Kubincanek, program coordinator at the Carnegie Library of Homestead. I asked her why she wanted her Homestead library community to read this book. She said, “It puts into words what many of the Homestead [communities] live with and probably don’t have the opportunity to think about in the way Sarah Smarsh does. Smarsh does a great job at balancing her personal perspective and the larger issues at hand in our country. Everyone could benefit from thinking critically about why being poor in America is so widespread and generational, but people in this area should especially. Her family’s experience losing their career in farming is very similar to the loss of steel mill jobs here, and I think many readers here would see that.”

I appreciated Kubincanek’s point in drawing an explicit connection between the conditions of poverty in rural America and the struggles many former mill towns in the Monongahela River Valley have faced in the last fifty years.

Tangible Community Connections Through Books

Conversation is the driving force of the ongoing partnership between the Carnegie Library of Homestead and CCAC. In addition to having free copies of Heartland available for library patrons, the library and CCAC cohosted a public discussion of the book. I attended this discussion as one of the panelists and enjoyed talking with folks about how Smarsh’s frank depictions of generational poverty reflect many of the conditions found in our own neighborhoods. People talked about access to resources like well-funded public schools and reliable transportation options as key factors in long-lasting feelings of isolation. Some participants talked about seeing the genuine desire of young people to be good and do good and expressed concern that the pressures of modern life might compromise or otherwise thwart their efforts. Everyone in the room thought Heartland would be worth discussing in a high school classroom, while also remarking on the quality of the writing and storytelling.

Our discussion returned several times to a core question: what can we do to help young people up and down the Mon Valley create opportunities that might actually allow them to not only benefit from economic revitalization efforts but also make strong and stable homes in a community? We returned again and again to some variation on the idea of what a postindustrial community could look like.

Rivers of Steel works with many libraries throughout the National Heritage Area, and we often advocate for creating meaningful community connections through reading. These efforts align with the goals of CCAC’s One Book Community Read program. I wanted to know more about how Heartland could be a means of bringing classroom discussion and community partnerships together. Additionally, I wanted to explore how Heartland brings together diverse audiences and creates opportunities for dialogue. Kubincanek discussed the necessary role public libraries play in sustaining communities, particularly poor rural communities that often struggle to maintain access to necessary resources. She says that through Smarsh, there’s a realization that “public libraries are not available for many rural families like they are here in our community.” She reflected that while neighbors “have barriers with transportation and scheduling like everywhere else in the country,” there is potential for a book like Heartland to be “a jumping off point for a conversation about what libraries can do for low-income people in a more urban community like [Homestead].”

When I asked both Kubincanek and Livingston about their favorite parts of Heartland, they both reflected on finding the moments of beauty and hope in hardship—that it is possible to break and heal from cycles of abuse and neglect, and that such instances of beauty are to be treasured. For me, I revisit the end of Smarsh’s memoir where she offers readers a final deconstruction of “The American Dream” as a “ghost haunting our way of thinking” rather than “a sacred contract worth signing toward some future,” where an oft-repeated ideal takes the form of a spector (288). In its place she offers the possibility that “what holds society together in a lasting way isn’t a calculated trade involving sacrifice, currency, and power—a wobbly claim that you get what you work for—but something more like a never-ending spiral of gifts” (288).

Dr. Kirsten L. Paine is an educator and researcher with more than a decade of experience working in higher education. She started working for Rivers of Steel in 2017 as a tour guide at the Carrie Blast Furnaces National Historic Landmark and was inspired by the mission to preserve such a national treasure held in public trust. Kirsten is committed to the work of public humanities education in her role as Site Management Coordinator and Interpretive Specialist. By creating and facilitating public programs that make the National Heritage Area’s history come alive for the community, she believes in archival study and teaching from primary sources as vital community resources.

Dr. Kirsten L. Paine is an educator and researcher with more than a decade of experience working in higher education. She started working for Rivers of Steel in 2017 as a tour guide at the Carrie Blast Furnaces National Historic Landmark and was inspired by the mission to preserve such a national treasure held in public trust. Kirsten is committed to the work of public humanities education in her role as Site Management Coordinator and Interpretive Specialist. By creating and facilitating public programs that make the National Heritage Area’s history come alive for the community, she believes in archival study and teaching from primary sources as vital community resources.

Enjoy Dr. Kirsten L. Paine’s article? Read another story from the A Literary Look series.