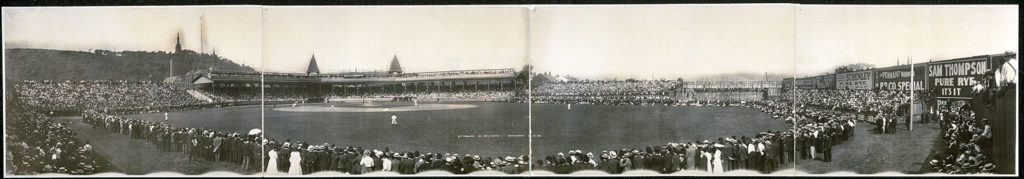

“Entrance to Forbes Field, Pittsburgh, PA.” Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, Detroit Publishing Company Collection.

By Ron Baraff, Director of Historic Resources and Facilities

The Origins of Pittsburgh’s Forbes Field

The Origins of Pittsburgh’s Forbes Field

Next weekend, Rivers of Steel will celebrate America’s Pastime with two baseball-themed films at the Carrie Carpool Cinema. This prompted Ron Baraff to look back at the origins of Pittsburgh’s Forbes Field and the place in holds in the hearts of many who visited this legendary ballpark.

For many baseball fans, there is more to the sport than the game that is played on the field. It has a history rich with colorful characters and places. Standing tall among these legendary characters of time are the ballparks. They are the “where” of the action and are inextricably woven into the very fabric of the nation’s sporting past. Within their “hallowed” walls, the fans felt like they were part of the game. A community existed where common ground was established on fond memories and cheers. The kinship of the fans related directly to the ambiance of the field. Here they were one, not of a diverse mind, but rather a singular pursuit. Never was this phenomenon more evident than in Pittsburgh—with its sixty-one-year love affair with Forbes Field.

Barney Dreyfuss’s Baseball Club

Barney Dreyfuss, a German-Jewish immigrant took control of the Pittsburgh Pirates baseball club before the start of the 1900 season. Over the course of the next eight years, the Pirates established themselves as one baseball’s premier franchises. They won National League pennants in 1901, 1902, and in 1903, the year in which they hosted the first modern World Series. In Dreyfuss’s thirty-two years as owner and president of the Pirates, they only finished out of the first division a total of six times. “I am a first-division club president, and I won’t stand for any second-division managers or teams.” It was precisely that attitude that drove the Pittsburgh franchise during his tenure as owner.

A Home at Exposition Park

Johnston, R. W., Copyright Claimant. Pittsburg vs. New York, Saturday, Aug. 5. Pennsylvania Pittsburgh United States, 1905. August 5. Photograph. https://www.loc.gov/item/2007663636/.

Home to the Pirates since 1891, Exposition Park, located approximately in the same location as current day PNC Park on the North Side, was not an ideal major league facility by any means. The structure certainly was no longer serviceable in the eyes of the forward-looking Dreyfuss, who remarked that, “The game was growing up, and patrons no longer were willing to put up with nineteenth century conditions.” The Park had many factors that inhibited its future success as a major league facility. Foremost was the problem of natural disasters. Because of its situation along the Allegheny River, the park was in peril of flooding whenever the river overflowed its banks. Floodgates were eventually placed on the sewers, but they were not very effective. The outfield was usually marshy, leading many to refer to the area as “Lake Dreyfuss.” In 1900, and again in 1901, high winds tore the roof off the grandstand.

Lake Dreyfuss—A view of Exposition Park and the surrounding area during the flood of March 28, 1913. It looks across the river from Monument Hill toward Downtown. “Exposition Park during 1913 Flood,” Pittsburgh City Photographer Collection, University of Pittsburgh, Historic Pittsburgh Archives.

Along with the problems incurred because of floods and winds, another worry for Dreyfuss was the issue of the park’s construction. Exposition Park’s grandstands, like all the other parks of its era, were constructed of wood. These structures were in continual need of upkeep. Without it, they were prone to rot, collapse, and of course, fire. Dreyfuss repeatedly attempted in the years that his Pirates were tenants in Exposition Park (1900 – 1909), to obtain a lease that would make “it feasible to rebuild the wooden stands,” yet he was constantly denied. Dreyfuss himself said of the conditions at Exposition Park:

It was impossible to build modern stands at Exposition Park because a lease could not be obtained for a term of years. Besides, we had more than a half dozen floods to contend with every year, and it often happened that after spending a great deal of money on repairs, all of our work was undone by a sudden flood.

Perhaps the most salient factor in Dreyfuss’s dissatisfaction with the park was its location. He saw the game as being a mode of entertainment that needed to attract larger and more affluent crowds than the usual working-class crowds that gathered at Exposition Park. For the game to survive and prosper in Pittsburgh, the Pirates, in Dreyfuss’s view had to have a more attractive location. He considered the area around the stadium to be dangerous and dirty, and felt that the “better class of citizens, especially when accompanied by their womenfolk, were loath to go there.” Dreyfuss reasoned that by attracting a more affluent class of fans, not only would attendance at the ball games increase, but so would profits. With these criteria in mind, Dreyfuss set out to find a desirable location to build his new park. He yearned for a showcase that would have its own personality, idiosyncrasies, and feel. He wanted it to be “state-of-the-art,” that it could serve as a source of pride for the community, the ball club, and himself.

Moreover, a new form of architecture was coming into being. In 1906, Frank Lloyd Wright made the use of steel reinforced concrete in the construction of his Unity Temple in Oak Park, Illinois. This technology was not only less expensive than building with stone, it also was more durable than using straight steel, which cracked easily. This use of reinforced concrete not only cut down on the amount of steel needed for construction, saving the builder money, but also increased the strength of the building and was fireproof as well. Until that time, even the new fields that had been built were still relying on the old process of wood construction. Barney Dreyfuss, was one of the owners who took notice of the new processes and was determined that his new park would be thoroughly modern in all respects.

Wooden fences and stands must go, just as frame structures and frame public buildings have been supplanted by fireproof structures…Steel and concrete stadiums will be the structures of the future.

A Fashionable Place to Build

“Landscaping at Schenley Park” Pittsburgh City Photographer Collection, University of Pittsburgh, Historic Pittsburgh Archives.

By 1908, it was becoming increasingly evident to Dreyfuss, that Pittsburgh’s growth would be centered in the East, around Oakland. It was there, that Dreyfuss turned his attention in his search for a new ballpark location. By the late 1890s, the East End of Pittsburgh was rapidly becoming the fashionable place to build. Pittsburgh’s growing elite of socially and politically ambitious families were settling in and around the area. In 1889, Mary Schenley, heir to a vast tract of land in Oakland, presented the city with three hundred acres of her property to be used as a park. One year later, Andrew Carnegie, chose a site at the entrance to the new Schenley Park as the location for his “gift to the people of Pittsburgh,” of a library, concert hall, and museum. With the addition of the new park and the Carnegie complex, thousands of people would be drawn to the area to “take advantage of its manifold facilities for learning and pleasure.”

Upon Mary Schenley’s death in 1903, Andrew Carnegie, John W. Herron, and Denny Brereton were appointed trustees of her estate. They set out to establish Oakland as the cultural and business center of Pittsburgh. In 1904, Carnegie broke ground for the Carnegie Technical Institute. Soon, he encouraged other Pittsburgh millionaires such as Henry Phipps, H.J. Heinz, Henry C. Frick, and the Mellon Brothers, to invest and build in the area. In 1905, Franklin Nicola, builder of the Hotel Schenley, along with his brother Oliver, owner of the Nicola Building Company, came to control, with the blessings of the Schenley trustees, vast tracts of the Schenley Estates. They incorporated their new holdings under the guise of the Schenley Farms Company.

Oakland also was home to the Casino Skating Rink, Schenley Oval Racetrack, and Luna Park, an amusement center that claimed to attract 25,000 customers a day during the summer months. There were some fifteen different trolley lines that regularly ran from downtown Pittsburgh to the eastern suburbs and were easily within walking distance of any proposed Oakland building site. These factors, along with Oakland’s advantage of being a transition community between blue-collar and white-collar Pittsburgh, served to hasten Dreyfuss’s decision.

A Home at the Entrance to Schenley Park

On October 18, 1908, after several months of negotiations, and lots of encouragement from Andrew Carnegie, Dreyfuss purchased nearly seven acres of land at the entrance to Schenley Park. The $250,000 land purchase was made from the Schenley Estate through E. C. Brainard and the Commonwealth Real Estate Company. The transaction was deemed to be the “largest real estate deal” to have taken place within the city in many years. In later years, Barney Dreyfuss liked to claim that when he bought the property, “There was nothing there but a livery stable, a hothouse, while a few cows roamed over the countryside.” The site, which was first proposed to him by Andrew Carnegie, was being used by Carnegie Technical Institute and the University of Pittsburgh as a football field. Moderately populated residential districts bound it on the West and the South.

Though Dreyfuss felt that he had found the perfect location for his new field, certain hurdles still had to be overcome for the project to be a success. Among the problems, was the natural landscape of the area. The site was not considered to be one of the better lots in the Oakland. It was at one end of a series of deep ravines that ran through the Schenley Park region. The main portion of the property was traversed by one of these ravines (Pierre Ravine) and would require a large amount of landfill before it could be useful. Only the northern portion was deemed to be suitable for building upon. Since most of the park would be open field, this it was felt, would not present a problem.

“Forbes Field, Pittsburgh, Pa.,” Between 1910 and 1915. Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, Detroit Publishing Company Collection.

When Dreyfuss agreed to purchase the land, he did so under certain conditions set forth by the Schenley Estate trustees. The trustees demanded that the structure be built of fireproof materials and be of a design that was in harmony with the other structures in the Park district.

Dreyfuss’s Folly

After an exhaustive search for an architect to build his new field, Dreyfuss chose Charles Wellford Leavitt, Jr., a 38-year-old, New York City civil engineer. Leavitt, preferred to think of himself, not as an architect, but rather as a “landscape design specialist.” Leavitt’s final design was elegantly simplistic. Emphasizing the park’s surroundings more than the structure itself, the only external extravagances were to be the buff terra-cotta fronts of the grandstands and the arched windows at the street level. Leavitt conceived of many revolutionary plans for the interior of the ballpark that included a three-tiered grandstand, and exposed bleachers that would be attached to the grandstand on the third base line. The grandstand seats would be accessible by a series of inclined ramps between the decks, eliminating the need for steps, thus easing fan movement. Elevators went from the main entrance to the third-tier boxes. Leavitt also incorporated plans for electric lights, public telephones, and have a seating capacity of 25,000, which would make it twice the size of Exposition Park and larger even than the Polo Grounds in New York. Yet, the proposed park size also became fodder for Dreyfuss’s critics, who claimed that there was no way that the Pirates could fill such a large venue and coined the new venue as “Dreyfuss’s Folly.”

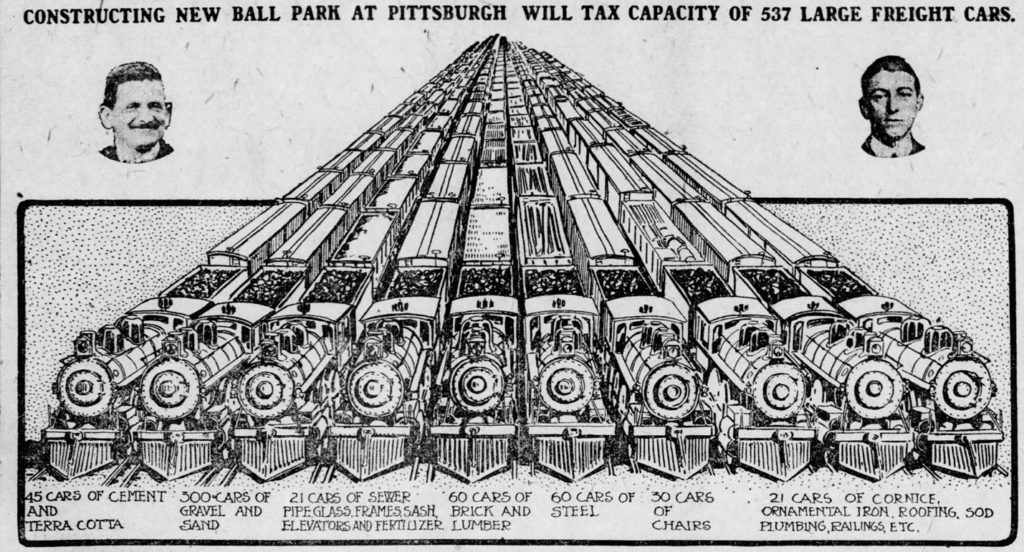

Dreyfuss chose the Nicola Building Company to build the park. Groundbreaking for the site took place on January 1, 1909. The job of filling in Pierre Ravine came first. This necessitated 11,155 tons of dirt and fill to be put in place. Grading of the field entailed the use of 60,000 cubic yards of earth, and the construction of the heavy retaining walls used to hold the fill, required 2,000 cubic yards of concrete.

Dreyfuss chose the Nicola Building Company to build the park. Groundbreaking for the site took place on January 1, 1909. The job of filling in Pierre Ravine came first. This necessitated 11,155 tons of dirt and fill to be put in place. Grading of the field entailed the use of 60,000 cubic yards of earth, and the construction of the heavy retaining walls used to hold the fill, required 2,000 cubic yards of concrete.

On February 26, 1909, the necessary building permits were obtained by the Nicola Company, for the construction of the $250,000 grandstands. The construction of the ballpark began on March 1. By March 21, the Raymond Piling Company had completed the foundation piles for the stands. Construction of the left field stands was finished one week later, well ahead of schedule. Beginning on March 29, the Nicola Building Company began to work double, eight-hour work shifts. The increased working hours, coupled with good weather allowed the work to progress rapidly. On May 9, the Pirates announced that the Park would open on June 30. The contract for the steel for the new park was awarded to the American Bridge Company, who supplied over 1,500 tons of structural steel. American Bridge, whose fabricating and manufacturing facility, located in Ambridge, PA and was the largest of its type, was part of J.P. Morgan’s United States Steel Company and a successor to Andrew Carnegie’s Keystone Bridge Company.

By June 13, most of the construction was complete. All the box seats had been sold, and the temporary bleachers finished. On June 16, the installation of the electrical wiring for the park began, as did the sodding of the field. Within a week, the last of the seats were installed. In all, to complete the construction of the park, it took 650 carloads of sand and gravel, 110 carloads of cement, 90 carloads of brick, 130 carloads of structural steel, 40 carloads of sewer pipe, glass frames and elevator materials, 40 carloads of ornamental iron, and 70 carloads of chairs. The final cost for Forbes Field, which took six months to complete, but required less than four months of actual construction time, was around $1 million dollars.

By June 13, most of the construction was complete. All the box seats had been sold, and the temporary bleachers finished. On June 16, the installation of the electrical wiring for the park began, as did the sodding of the field. Within a week, the last of the seats were installed. In all, to complete the construction of the park, it took 650 carloads of sand and gravel, 110 carloads of cement, 90 carloads of brick, 130 carloads of structural steel, 40 carloads of sewer pipe, glass frames and elevator materials, 40 carloads of ornamental iron, and 70 carloads of chairs. The final cost for Forbes Field, which took six months to complete, but required less than four months of actual construction time, was around $1 million dollars.

Exterior of Forbes Field, a baseball stadium, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. Pennsylvania Pittsburgh, ca. 1909. https://www.loc.gov/item/95503573/.

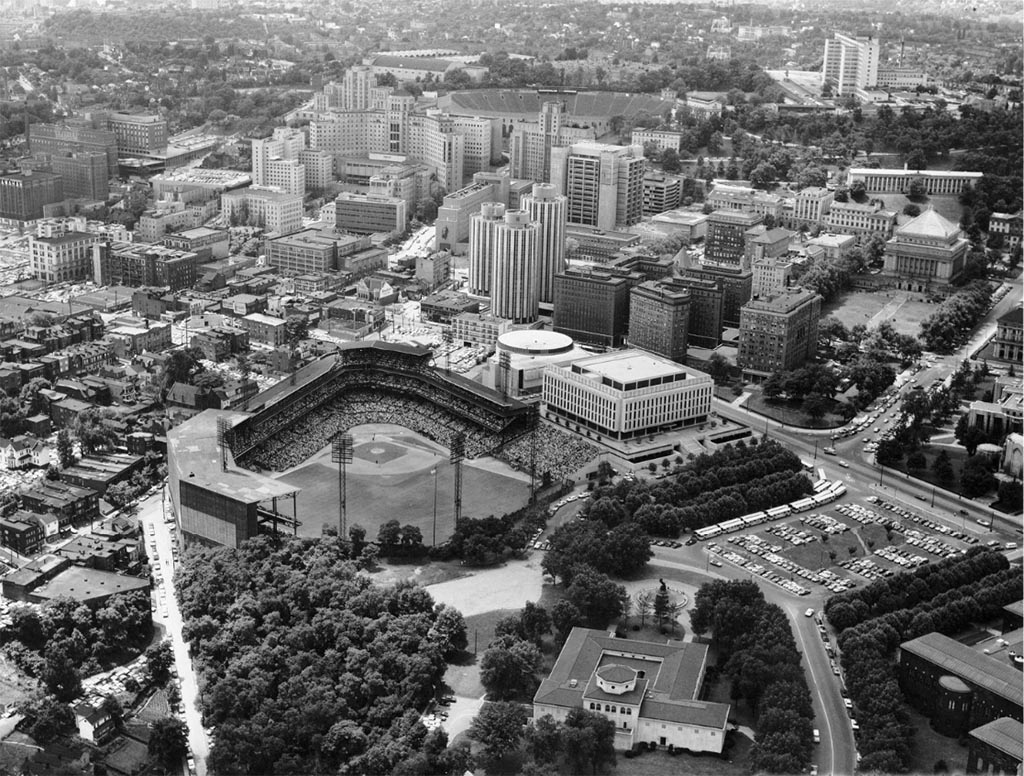

Within the history of Pittsburgh and the western Pennsylvania region, Forbes Field stands as landmark. From 1909 until it was vacated in 1970, it served the area as not only a venue for sporting events, but as an arena for political rallies, circuses, religious revivals, cultural events, and more. Very few Pittsburghers during its lifespan were exempt from its influence. At one point or another, no matter what their station in life, they had gathered within its perimeters and taken in its ambiance. It was a place where bonds were made and memories cast. Generations of Pittsburghers were able to share in its memory, hearkening back to a time when they could look out beyond its walls and feel as though they were a part of the neighborhood—all the while soaking in the green terrain that surrounded them. In Forbes Field, there was a sense of community that no longer exists, except within the precious memories of its loyal patrons. It is there, that it will live on and forever be cherished, thanks to Barney Dreyfuss’s folly.

Forbes Field in Photos, Later Years

View of the Schenley Park Entrance, taken from the 2st Floor of the Cathedral of Learning showing Forbes Field, the Carnegie Library, and the Mary Schenley Memorial Fountain. “Schenley Park and Forbes Field,” 1936. Pittsburgh City Photographer Collection, University of Pittsburgh, Historic Pittsburgh Archives.

Aerial view of Forbes Field and Oakland,” 1968 / 1970. Allegheny Conference on Community Development Photographs Collection, Detre Library & Archives, Heinz History Center, Historic Pittsburgh Archives.

An avid baseball fan and historian, Ron Baraff’s passions intersect when it comes to the Josh Gibson Collection of the Rivers of Steel Archives. If you like to read about Pittsburgh’s baseball legacies, you’ll probably want to check out Ron’s piece Josh Gibson Gets His Due from earlier this year.

The Origins of Pittsburgh’s Forbes Field

The Origins of Pittsburgh’s Forbes Field