Artist Benjamin Aysan with First Lady Frances Wolf and Governor Tom Wolf

Heritage Highlights

Communities are built by sharing and traditions are built by sharing across generations.

At Rivers of Steel, our Heritage Arts program brings attention to arts that shape communities, passed down across time from one artist to another. That’s why we’re launching our new interview series, Heritage Highlights, where we will be showcasing artists who work within local traditions and communities.

For our first installment, we spoke with Benjamin Aysan, an accomplished calligrapher and Turkish immigrant to Western Pennsylvania. Benjamin shared with us the roots of Turkish calligraphy and how artists like him have changed it in the modern day.

An Interview with Benjamin Aysan

Benjamin Aysan

Rivers of Steel (RoS): What heritage art do you make and how?

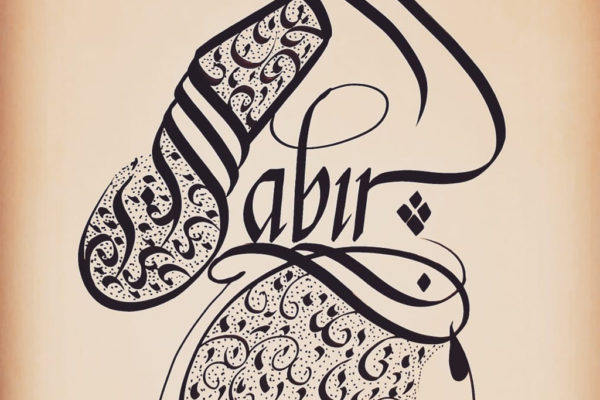

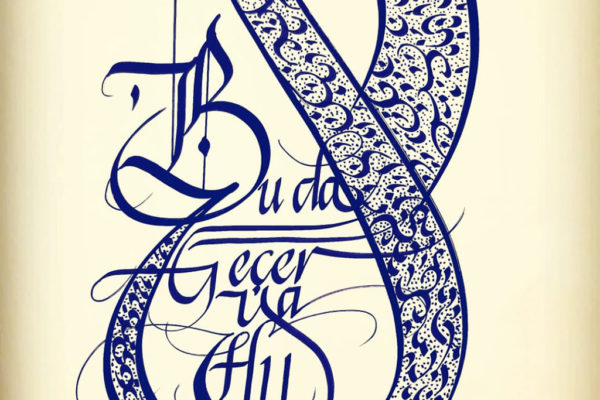

Benjamin Aysan (BA): I do calligraphy using italic letters for custom design art works. I can write names and quotes on any smooth surface: wood, ceramic, leather, etc. for wedding ceremonies, invitation cards, and so on. It depends on what customers order. I use parallel pilot pens, fabrications, and chisel-type pens with varying sizes.

RoS: Who taught you your art?

BA: Eight years ago, I was working as an event and facility manager at the Pacifica Institute in Salt Lake City, Utah. We invited a well-known calligraphy artist from Turkey to our organized friendship dinner. His name is Aydin Cayirli. He was dancing with the letters, using the pens as a part of his hand, and all the watchers admired him. The same day, I invited him to my home to show our hospitality and he gave me more advice about his art. His first tip was “Do not give up, and make more practice”. Since then, I have worked three hours daily and, after one year, I joined a big festival called “Living Tradition” in Salt Lake City. That was my first time meeting people with my art and I was encouraged because people liked it.

We moved from Salt Lake City to Erie, Pennsylvania in August 2015, as I became the executive director of the Erie Turkish Cultural Center. During the past five years, I have been invited as a calligraphy artist many times to friendship dinners in different states on the East Coast, festivals, activities, and as a guest to Governor Tom Wolf`s residence.

Mr. Cayirli`s advice “do not give up” always motivates me.

RoS: What community did this art come from?

BA: Turkish calligraphy is a unique artistic creation, although calligraphy itself is not of Turkish origin. The Ottomans adopted it with religious fervor and inspiration, taking this art to its pinnacle over a five-hundred-year period.

RoS: What community inspires your art?

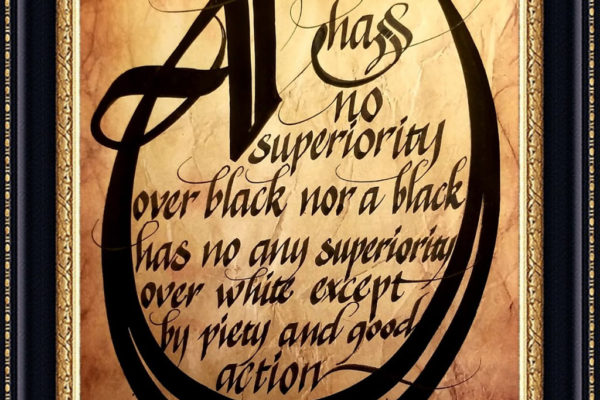

BA: I don’t have a specific community that inspires me. I make art to reach other communities and cultures, and to improve my art skills. It is a bridge between different cultural backgrounds. When I make art, it makes me feel more connected to the people around me, because the artist is the same as the community.

RoS: From what history did this art emerge? How has it changed over time?

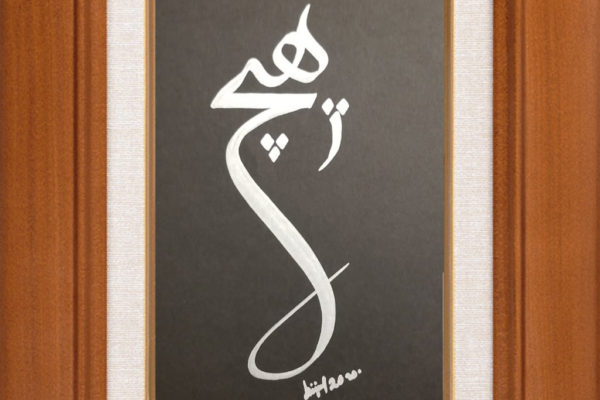

BA: The literal meaning of the Turkish word for calligraphy (hat) is line or way. In essence, Husn-i Hat—calligraphy that uses Arabic letters—comprises the beautiful lines inscribed with reed pens on paper using ink made from soot. In the 13th century, Yakut-ul-Mustasimi, a calligraphist from Amasya, made a breakthrough by using nibs of various widths and sizes in one composition. Later calligraphists followed and developed his methods.

In modern day Turkey, there are two types of calligraphy. The first one is Arabic calligraphy using Arabic letters, Husn-i Hat. In Islam, calligraphy was practiced by writing sections from the Qur’an and hadiths (prophet’s words) and then hanging the copies up in mosques. The other type, which I do, is modern Turkish calligraphy using Latin letters. After the founding of the Turkish Republic, calligraphy written with italic Latin letters became very widespread.

RoS: What is the most beautiful thing you have ever made?

BA: I think, to this day, the most beautiful thing I have made was the piece that I made as a gift for Governor Wolf and first lady Frances Wolf. [Pictured at the top of this page.]

View Benjamin Aysan’s work in the videos and gallery below. In these videos, recorded in the summer of 2020, Benjamin talks about the differences between American and Turkish calligraphy cultures and the need for patience and decency in art.