Collaborators with the Currents program: (Top row from left) Alison Zapata, Lindsay Huff, Jon Engel, Katy DeMent, Til Gurung, and Chitra Gurung. (Seated from left) Benjamin Aysan and Gloria Bal. Participating, but not shown here, is artist Jennie Reyes.

Heritage Highlights

Rivers of Steel’s Heritage Arts program strives to represent the region’s diverse cultural heritage—from ethnic customs and industrial arts directly linked to the Heritage Area’s past to contemporary folk arts and cultural practices emerging from the region’s diverse urban and rural experiences. Usually passed down from person to person within close-knit communities, these traditions are as varied as they are unique, each representing another part of southwestern Pennsylvania’s rich ways of life.

Earlier this year, our Heritage Arts Coordinator, Jon Engel, teamed up with the Pittsburgh Center for Arts & Media (PCA&M) for a community-building project, dubbed Currents, that collaborated with new American groups in the city of Pittsburgh. Jon and several of PCA&M’s staff artists led an educational program for immigrant tradition-bearers, culminating in a series of free arts workshops for their communities. At the end of their year together, these traditional artists left with a new network of mentors and new ways to share their cultural skills with others. In this article, Jon speaks with each of the artists, as well as leaders from their communities, about why this series and these traditions are so vital and important to their people.

Currents Traditional Arts Education Training

By Jon Engel

A Reflection On Connection

It’s easy for me to take my daily life for granted—the same work, the same food, the same commute. While routine can fade easily into boredom, it is actually made up of a thousand things—traditions and value systems emanating from complex cultures and histories. I love my job because it surrounds me with people from incredibly different cultures who have unique stories to share. These individuals’ journeys are quite unlike my own, yet I consistently connect with them, understanding where our similarities converge. Recognizing that in one another has been a form of incredible awakening that for me has been enlightening.

Last April, the light shone in as I ate dinner at the home of Benjamin Aysan, a Currents artist and traditional Turkish calligrapher. We were sharing chicken and roasted potatoes, just as I would at any of my grandfather’s Christmas dinners. However, this was an iftar, a Ramadan feast. For one month, practicing Muslims fast from sunrise to sunset, denying themselves sustenance so as to strengthen their own contemplation of God and their relationship to compassion. At the end of each day, they hold one of these dinners, trading food between family members. On this occasion, Benjamin and his family shared their meal with the rest of the Currents cohort and me. We ate as Benjamin spoke about the deep wisdom of his people, the things that Ramadan teaches and the people it brings together. I sat and listened, seated among engineers, bakers, and rice farmers from all around the world, artists all, and thought fondly about my dad’s potatoes.

The collaborators of the Currents project, gathered with their immediate families at Benjamin Aysan’s home in April 2023.

Traditions like this are built to foster intimacy. In part, that is why they are so valuable. Prior to that dinner, the team at PCA&M, which included Mary Brenholts, their director of artists in schools and communities, along with teaching artists Katy DeMent, Lindsay Huff, and Alison Zapata, worked with Rivers of Steel and the community artists for six months. Our goal: to translate that intangible value into a series of arts workshops, highlighting the unique traditions of the artists—and their communities—who gathered for this special meal.

In addition to Benjamin, three more artists were nominated by a Pittsburgh Area ethnic center representing their communities. They included Gloria Bal, who also originated from Turkey, Chitra Gurung of Bhutan, and Jennie Reyes of the Philippines.

Benjamin, Gloria, Chitra, and Jennie were selected based on their expertise in traditional forms, along with their desire to share that expertise with the people around them. Under the guidance of Katy, Lindsay, and Alison, each artist created a lesson plan that communicated their skills and gave context as to why their practice was so important to their community. Afterward, they taught these lesson plans to other members of their community in a free gathering at their ethnic center.

Starting this fall, these lesson plans will available at various local libraries. For now, it is my deepest honor to introduce you to the Currents cohort of 2023.

Our Traditional Artists

A group of middle schoolers gathers around Gloria Bal at the Turkish Cultural Center to learn the water marbling process.

Gloria Bal with the Turkish Cultural Center

Gloria Bal was born in Istanbul, the capital of Turkey, where she studied to be a teacher. Since moving to the United States to complete her Master’s degree, she has taken an interest in ebru, a traditional Turkish form of water marbling. In this art, Gloria uses natural products like ox gall to thicken a tray of water, transforming it into a fluid yet jelly-like substance. She then draws on the water with special ebru paints that float on the surface, instead of dispersing through the liquid, allowing the waves and ripples to shape the image. She uses these properties to make images like flowers and hearts, which she can copy onto paper by laying it on the water.

“In this art, the tulip shape is important,” she says, “It is a symbol for Turkish culture. Because a tulip comes from a single bulb, it symbolizes the one and only oneness of God. Ebru has a big philosophy behind it.”

Midway through the process of creating an ebru artwork. The paint has been applied over the water and designs have been created within it. Placing paper over the design is the next step.

Historically, ebru was often practiced by dervishes, a kind of Islamic mystic. Echoing this, Gloria finds it deeply spiritual and calming. “This art teaches us to be patient because when you’re doing it, you can’t do it fast. You need to be slow and focused. And you can’t do the same thing with the water every time, you’re going to do it different.”

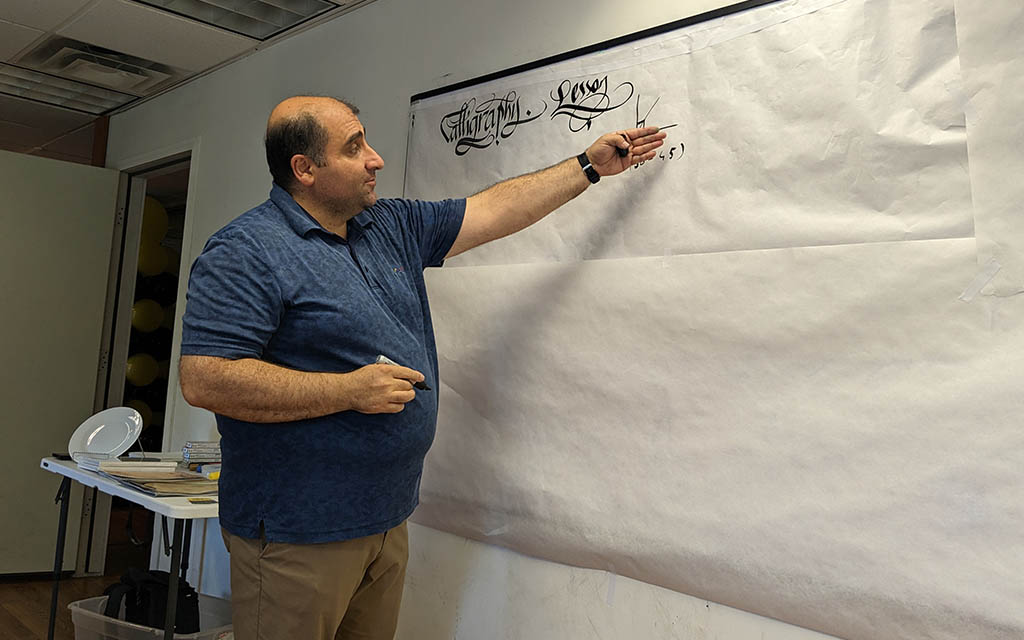

Artist Benjamin Aysan demonstrates the angles desired as he workshops his calligraphy lesson.

Benjamin Aysan with the Turkish Cultural Center

Once used primarily to decorate mosques and copies of the Quran, calligraphy has a very similar place in Turkey. “In many different cultures,” Benjamin says, “calligraphy has significant cultural and historical importance. In addition to being a beautiful art form, it is a way to celebrate and preserve that cultural history via the written word.”

On top of his calligraphy practice, Benjamin is also the outreach coordinator for the Turkish Cultural Center Pittsburgh, located just off Banksville Road. In both this role and his work as an artist, he seeks to connect Turkish culture to other cultures. “We focus on fostering cross-cultural dialogue, comprehension, and appreciation. Providing opportunities for people from all backgrounds to learn about Turkish culture, art, and customs, workshops aid in the achievement of these objectives.”

“Programs like Currents provide possibilities for visibility, teamwork, and skill development,” he adds. “That makes it easier for artists to communicate with audiences and other artists, encouraging participants to appreciate and understand one another.”

Jennie Reyes shows off various Philippine fabrics.

Jennie Reyes with the Filipino American Association of Pittsburgh

Jennie Reyes grew up in the town of Daraga, Albay, in the southeast of Luzon, the main island of the Philippines. Growing up, her family ran a manufacturing business, which produced housewares, handbags, novelties, and more from the island’s natural materials, and sold them for export. These materials included plants like seagrass, rattan, wicker, and abacá. The abacá is a Filipino banana plant, the leaves of which can be processed into an extremely strong fiber sometimes called “Manila hemp.” Jennie worked as the head of product development for her family’s company and learned a deep reverence for this material from the artisans her family employed on their production lines. She learned how to weave abacá by traveling across the Philippines and the world for trade shows and observing the local techniques these merchants brought with them.

“I have been surrounded by beautiful handmade products,” Jennie says of her work. “I would like to emphasize their importance because there are only a few small cottage industries and villages that are engaged in creative handmade weaving. In this age of technology, I think It is important to preserve and continue the traditions of hand-weaving of abacá fibers.”

Lani Mears, president of the Filipino Association, personally recommended Jennie explore teaching through the Currents program. “According to the unofficial results of the census in 2020, there are over 8,500 Filipinos in the greater Pittsburgh region,” she says. “A significant portion of the Filipino immigrants are in mixed marriages, so it’s very crucial for us to promote programs that educate the partners and the children about our backgrounds, our heritage, and our culture.”

“Workshops like the one conducted by Jennie highlight the livelihood and crafts of our people. They provide Filipinos who attend them a feeling of pride and self-identity. And, because the workshops are open to non-Filipinos, we are also providing opportunities for much deeper relationships and mutual understanding.”

Chitra Gurung, left, instructs a Bhutanese American man, sharing how to create a ghum—a woven umbrella traditionally used by rice farmers.

Chitra Gurung with the Himalayan Foundation-USA

In the past fifteen years, Pittsburgh has become home to thousands of Bhutanese Americans, many of them originating from rural villages high in the Himalayan mountains. These villagers, largely descended from groups who migrated north from Nepal centuries ago, are members of a vast array of ethnic groups and religions. Each has their own unique farming methods, ceremonies, and cultural traditions. They are unified primarily by their use of the Nepali language, as opposed to the Dzongkha language favored by Bhutan’s primarily Buddhist ethnic majority. In the 1980s and ’90s, the Bhutanese government heavily persecuted Nepali speakers and other village people, categorizing them as “illegal immigrants” and denying them their rights to property and / or their traditional religious beliefs. Many people were displaced as they lost their homes or fled oppression, leading to the establishment of massive refugee camps in Nepal, where cultures intermingled and traditions were adapted for their new circumstances.

In 2008, the United Nations began to voluntarily resettle many people in those camps to new countries, with the United States taking in around 60,000 people. Since then, Pittsburgh has become a major cultural hub for Bhutanese American communities, first as a city where many were settled and then as thriving communities as folks flocked to live alongside friends, family, and others who spoke their language. These communities vary vastly in age and experience, ranging from elders who spent the majority of their life in the homeland to young children who have never left this city. In times like these, artisans like Chitra Gurung have become vastly important to their people as guardians of memory.

Chitra was born in the village of Gairigaon in the Sipsoo area of southwestern Bhutan. He is a craftsman of many talents, including woodcarving and weaving, which he primarily used to create tools, baskets, and other utilitarian items on his family’s farm. After the displacement of his village, he lived for a while in the refugee camps. There, he applied his skills to survive in a very different reality—learning, for instance, to weave with strips of fiber torn from plastic packaging rather than split from bamboo stocks. Since moving to Pittsburgh, he has become a gardener here as well, adopting power tools and store-bought twine. His craft practices are thus more than practical but are also records of the many ways he has lived his life and the experiences these disparate peoples have shared.

Chitra also works closely with Himalayan Foundation-USA, a Pittsburgh-based nonprofit that helps to preserve memories of life in Bhutan and in the camps while also working to sustain the shared community of Bhutanese Americans. They offer many social programs, particularly to elders and youth, and are working toward the creation of a museum in Pittsburgh that will honor each of the individual Himalayan ethnicities now living here. At the workshop led by Chitra, elders worked together to create a ghum—a woven umbrella for rice farmers—but also sang, danced, and discussed times gone by.

“Elderly people are isolated, even within their family,” says Til Gurung, president of the Himalayan Foundation, “because the subject of their interest—their skills, their experiences— are totally different to their children and grandchildren. They don’t have much opportunity to express their feelings, to share their experience, to tell their stories.”

“But this type of project, the workshop and the get-together, gives them this opportunity to share with their friends who really understand and have similar experiences.”

Jon Engel is the Heritage Arts Coordinator for Rivers of Steel and the author of the Heritage Highlights column.

Jon Engel is the Heritage Arts Coordinator for Rivers of Steel and the author of the Heritage Highlights column.

To read more about local traditional artists, check out the other articles in our Heritage Highlights series, including this piece about Ukrainian pysanky in Carnegie. To see more of our work with Benjamin, you can read our interview with him from 2021 or check out this calligraphy tutorial he made with us last year. If you’d like to learn more about the process of water marbling or even try it for yourself, check out this heritage craft tutorial and kit that highlight Gloria Bal’s practice.