Ed Parrish, Jr. during an iron pour at the Carrie Blast Furnaces, fall 2020. Photo by Richard Kelly.

Profiles in Steel

Rivers of Steel is excited to launch a new series that shines a spotlight on the talented members of our organization’s community. From staff and volunteers to collaborators and patrons, it takes a dedicated group with many and varied talents to support the community-based initiatives offered through Rivers of Steel.

In this installment, we meet Ed Parrish, Jr., our furnace master and metal arts coordinator. Ed has worked with Rivers of Steel since 2016, heading our Hot Metal Happenings and other industrial arts programming. He is also a talented sculptor who works in iron and other metals. You can view his work at the ZYNKA Gallery in Sharpsburg until the end of May in the exhibition Labour of Love, a two-person show with painter Jack Taylor, curated by Jeff Jarzynka.

An Interview with Ed Parrish, Jr.

By Jon Engel

The first time I met Ed was at the Festival of Combustion in 2019. He was armored in the iconic metalworker’s suit: thick protective jackets of layered leather, dark brown and uniform, with glass shields hanging over the face. Molten aluminum flowed from a massive bucket down into a line of sand molds, burning orange under the shadow of the Carrie Furnaces. Sparks sputtered by the dozen busy workers in our Metal Arts team, all of them working in tandem to ensure the foundry process went off without a hitch. In all honesty, I was pretty intimidated: the second a piece of metal starts to glow and warp, my first instinct is to put soles to the street and skedaddle, as it were.

In contrast, Ed himself is cool and breezy. “I’d like to sell this and put it on someone’s wall,” he remarked, gesturing to one of the 250 pound pieces in Labour of Love, “This stuff’s heavy so I’m not trying to haul it around forever.” We talked about his work, as a solo artist and a metalworker with Rivers of Steel, and what draws him to sculpting in the foundry…

Packing the Sand

Ed Parrish, Jr.

So first off, you went to art school…

Yeah, in North Carolina. East Carolina University.

You from North Carolina?

Yes. This little town called Rocky Mount. It’s right about 45 minutes from the Virginia border. If you’ve ever driven south on 95, you’ve seen signs for it: “Rocky Mount”, then “Miami”. But I’ve lived in Pittsburgh since the late ‘90s.

How’d you end up here?

I moved here with a friend shortly after college. And every time I tried to leave, it was like, for where? For what?

I’d been through Pittsburgh a couple times before, coming up from North Carolina. I used to pour a lot in Buffalo. And I was drawn to the kind of Rust Belt jam here and, like, the history of industry and metal work here. And it was cheap. It was like, do I wanna’ move to New York or…

Or Pittsburgh?

Or Pittsburgh.

I imagine most people around here get into metal arts through, like, they’re from here and this is history and the heritage around here. But it seems like you were already interested in metal arts and moved here because this was the logical place for that.

Yeah, I was into metalworking from college and Pittsburgh seemed like a good spot—although, when I moved here, no one was casting iron here. Carnegie Mellon, at that point, still had a foundry for bronze and aluminum, but that also got eliminated at some point after that. I was actually the first person to ever cast iron in Pittsburgh for artmaking purposes. We poured the first metal, at Carrie Furnaces, that had ever been poured there since the mills closed—which was kinda’ cool.

So, iron, specifically, is what you’re interested in?

I mean, primarily, yeah. Iron, as a metal, that was the one that I first became interested in, for casting purposes. It was more just a connection to the material and its connection to the Earth. Like, the center of the Earth is molten iron, so that was always a draw for it, conceptually, as a material. And the aesthetics of iron, I was drawn to those.

Casting iron is a much more involved process than casting aluminum or bronze. It’s more of a team sport or a group activity. And there’s always, like—there’s “heads” that travel around to iron pours around the country like people would follow around the Grateful Dead.

Ironheads?

Yeah! There’s a community like that around the process. And it’s something you can do in your backyard, but to do it at scale, it’s tough to do when you’re out of college and you don’t have access to stuff like that. So, early on, when I started pouring in Pittsburgh, we got a Sprout Fund grant to fund it and we did these traveling, kind of performative iron pouring demonstrations around town. And that’s when we got started doing that here again.

Anymore, it’s fun to travel to go iron pours, sure. But I have a really nice set-up at home [Carrie Blast Furnaces], so it’s less about traveling for the need to make work than it is about the community and to go to different places and make friends.

It’s interesting to hear you talk about it as a community, because I know Carrie is like that to Shane [Pilster] and the graffiti artists. That Carrie can serve the same function for you guys, that’s interesting to me.

Yeah, well, a lot of universities are kind of dropping their hands-on foundry programs. You have some of them pop-up, but… as that falls out, alternative places like Carrie and alternative venues pick up the slack and provides places for artists to do stuff like this outside of the university. And for people that are getting out of school or didn’t go to school and don’t have access, it gives people like that an opportunity to work in the medium.

How did you get work after college?

When I moved to Pittsburgh, I worked at a place called Iron Eden, doing ornamental ironwork and custom fabrication. Then I ran my own shop called Red Star Iron Works for years, then I just got kind of burned out on it and walked off and made art. Then I worked in the film business, did that for a while. It’s a lot more profitable than making art.

(laughs) You say that so dispassionately. “Oh yeah, I was in the film business for a while, I did that and eh”-

Well, I got into the film business because, I used to have a studio space in a building over in Etna, and there was a fire in the building, and I lost all my stuff. And I was making work out of there that was paying the bills. So a bud that was working in the film business goes, “hey, you might need work right now, do you wanna come work as a painter on this movie?” That was The Road, the first movie I worked on. Kind of a bummer, the movie, but it was good. Not super “feel good”.

I did that for a long time and I just had to get out of it, because my daughter had to live with me with full time again. So I had to be around with her more than I had to make money. So I took the pay cut, figured it out, and went back on my full time dad duty, which—that’s my actual favorite activity anyway.

Ed and the metal arts team during an iron pour, September, 2020. Photo by Richard Kelly.

Pouring the Cast

It seems like the way you got started in the metal arts was academic, in that you started at university. Is that how most people get into this field? Or was that the case at the time? ‘cause it seems like the spaces are shifting.

Art iron casting is pretty removed from the industrial foundries. It’s a real do-it-yourself kind of thing. For iron furnaces, I’ve never operated a furnace that wasn’t hand-built, homemade by someone I was working with. Apparently, industry was like, at one point, “a cupola is not gonna’ function, at that scale, for what you guys are trying to do.” So the old white beard dudes were, like, “OK, now we’re gonna’ have the smallest cupola festival to see how small we can make this work.”

What is a cupola, by the way?

A cupola is a coke-fired furnace for melting iron. It’s basically the furnaces at Carrie, those are just big cupola furnaces.

So building the smallest one you can that can still get hot enough to melt iron, not easy?

Yeah, I think it ended up being like three, four inches. And they would nerd out and make little tools and stuff for it. It’s pretty cute.

It’s interesting that you make this distinction between industry and art foundry. Working at Carrie, what is the relationship between the industrial history and the industry people who are still attached to that to your art and your program?

Well, I mean, the process is the same, largely. Us melting metal is not terribly different than people melting metal in the industry. Except for now, there aren’t many coke-fired iron foundries anymore in this country. It’s a lineage, y’know? It’s taking the industrial process and experimenting with it to make. These are simple, two-part, cope-and-drag molds for most of the things we do, so not all the technique that it would take the part for a car, but it’s the same process. But they won’t usually use cardboard, bubblewrap, and bull**** for their mold patterns.

Most of the people I know from industry who see us, they’re like “Oh, you’re just doing this for ****s and giggles? Just because?” It’s kind of hard not to respect that, if you have any respect for the process at all. If you’re like, “I hate it, I worked in the mill for years, why would you do that?”, that’s also (laughs) a pretty valid response. But I think most people are into it, they’re stoked to see people doing the work and keeping things going.

I’ve often joked I should have been a painter. It’s easier, and I still end up painting these things anyway.

As a sculptor, what about metal works grabbed you and made you say, I wanna’ do this?

Psychologically, it’s, like, the transformative process. Especially with this work at ZYNKA, using garbage and discarded materials, very temporal things, and then transforming that into something that’s relatively permanent…

What did these pieces start as, material-wise?

They’re a wide variety. There’s a lot of use of cardboard in a lot of these—it’s a very democratic material, everyone has access to it. And random stuff from the thrift store, like toys and craft materials. There are bottle nipples in one.

It’s a mold-making process, right—you make your pattern for the thing, either out of wood or all this stuff. These [the works in Labour of Love] are all cast from resin-bonded sand molds. It’s a two-part chemical, the catalyst and resin. Then you mix that in the sand, make a shape or a “flask” around the pattern in the mold, pack the sand, and flip it over, pack your lid. When you take it apart and take all the stuff out of there, you’ll have a void in the sand block. That’s your mold.

Then you make a “gate”, which is like a road, from the edge of the mold into your piece, so you can pour the metal. And you’ll need vents so the air can get out and doesn’t make an air bubble in the metal. Then you pour the iron in. The sand is a waste material, it’s a one-shot mold.

So these are all unique?

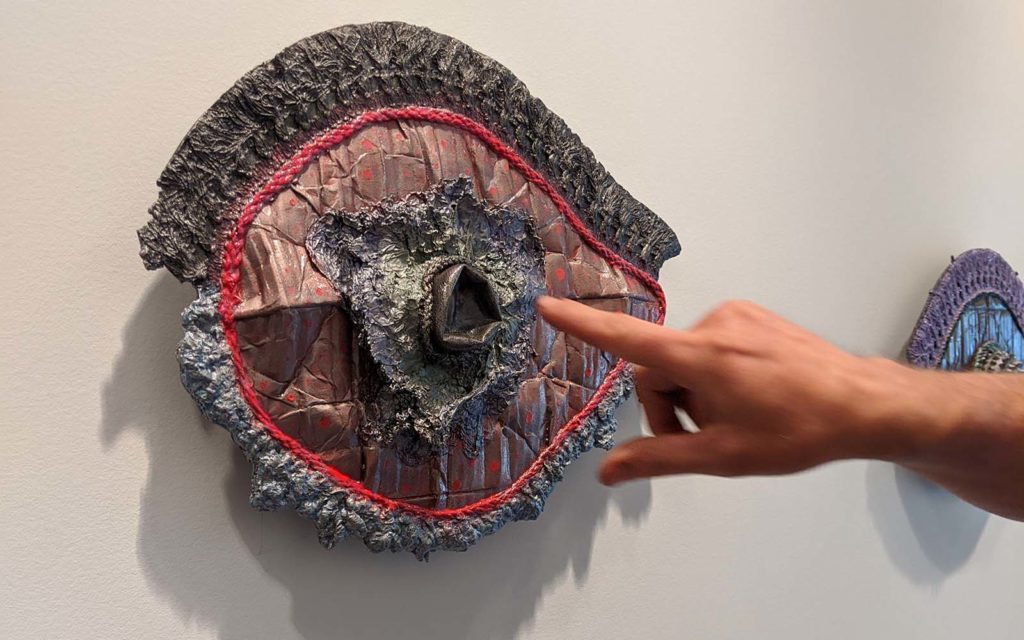

Yeah. There’s some of them where I recycled the patterns, like these two eyes. That was the first pull off the pattern, then that was the second pull off that pattern. So you can see, that iris was a plastic grocery bag material? When I pulled that first one out, that bag kind of blew out. So I just poked it in the eye and made another one.

I’ve been working with some of these patterns, especially the heads, for a while and reworked them. But this is probably my last show that’s gonna’ be all wall work, for a while. I’ve been working on wall pieces for a minute, not really doing much in the round, but I used to do a lot of installations, using some of the more temporal pattern pieces along with the metal.

So there’s a lot of steps. There’s a lot of steps that don’t involve touching the metal. Actually casting the pieces is one of the shortest parts. You get to touch the metal when it’s done, but I spend a lot more time with a hot glue gun and a paintbrush than I do actually, like, manipulating the metal for these pieces.

Ed Parrish points at the iris in his eye sculpture in the ZYNKA Gallery.

Breaking the Mold

So how did you end up working at Carrie?

I had worked with Ron [Baraff] before on an iron pour at the Pump House, probably in ’07. Then I did the casting for the Iron Garden project down there with my friends Josh and Addy and the Penn State Master Gardeners project. We did all the mold-making at my shop in Lawrenceville, 39th St, which has since been torn down to make room for condos. Then we did the pour at Carrie and installed those pieces and, after that, we really got the ball rolling to do more metal programming. It was kind of around the first time that Chris [McGinnis] was doing the Alloy program down there and Rivers of Steel was starting to get into more art programming,

And then, during the pandemic, Metal Arts was some of the only stuff that kept going. The facilities at Carrie are so big and so much of our work is outdoors so we were able to do a lot of socially-distanced programming, with Hot Metal Happenings and our doodle bowls.

A “Hot Metal Happening” at Touchstone Center for Crafts, 2019.

How did the Hot Metal Happenings happen?

That was programming I developed back in 2007. That was our name for our traveling foundry show, so it was easy to adapt to what we’re doing now. For the traveling pours, we mostly stick to aluminum pours. It’s a much easier lift, both weight-wise and the amount of crew. You can pour aluminum with three people. Pouring iron with three people, you’re not gonna’ be having a good time. It’s just too much work. Especially for the scale we do at Carrie, you want 10-15 people, at minimum.

So aluminum is easier?

Takes less heat, takes less materials. You can just pick up aluminum and get to work like– (clicks tongue).

Dipping into my Pittsburgh history, both aluminum and iron have been produced at an industrial scale here. The raw materials are mined here, right?

Yeah, the coal mines. The rock around here is basically coal, limestone, and iron ore. A lot of coal was imported here, transportation plays a huge role in Pittsburgh, but a lot of coal here too. So a lot of iron ore.

These minerals have taken on a kind of identarian role, almost spiritual role, for the people of Pittsburgh for nearly 200 years, because that’s what the economy has always been based on. I mean, we’re called “Rivers of Steel” – that’s what we identify by. What it’s like coming from North Carolina to a place like “the Rust Belt” that defines itself by this kind of material and this kind of work?

For me, I grew up in a working class family, so I have that kind of background. It makes sense to me. I identify with blue collar stuff. It’s a pretty natural shift, for me, to Pittsburgh, as far as that feeling. But also I always spent a fair bit of time in Appalachia, so I figured I should come to the Paris of it.

(laughs) Metal arts to me seems like a pretty “working class” field. Most of the people who end up in it identify with that idea?

Yeah. And, for me, even when I was in art school, the work that I was paying more attention to was more like craft and folk kind of art, what people describe as “outsider art”. I always respond to the rawness of that more so than hyper-conceptualized work that doesn’t have as much tooth to it at times. So there’s the grit of that that I always enjoyed. That’s one of the things that drew me to Pittsburgh originally, too. It’s fading away, you still have parts of Pittsburgh like this, but Pittsburgh used to be pretty grimy. And as much as I enjoy working class and blue collar stuff too, it’s also nice to have conversations with people who have expanded their brain beyond that kind of mentality and mind set… As much as my work is influenced by industrial history, working class stuff, it’s doing its own thing, too.

Ed’s artworks on display at the ZYNKA Gallery.

Why faces?

Well, I was playing with more abstract kind of imagery, more cellular. With the faces, I made one and went, “That’s kind of like derp-y face”, and I was like, “Yeah, I’ll make more faces.” People relate to it. That’s how people communicate now, with little cartoon faces. And it’s also considering the idea of a mask, of an emotion, and seeing… seeing life and expression in everything? I’ll see a piece of cardboard on the side of the road, a sweet, wrinkled, rain-damaged piece of cardboard, and I’m like, “Oh yeah, get that!” I look at the age and character, what can be expressed in a piece of cardboard.

My experience with metal art is, it scares the **** out of me, to this day. It feels very, like, inert and lifeless. But the work you’re doing is very against that. It’s very cute, and kooky, it’s fun. It makes an interesting contrast to what I expect. Like, there is life in this.

Even before the paint, I think there’s a lot of life in this work. There’s movement. A lot of this work I started making while processing a lot of loss. There was a lot of mourning process when creating these pieces, while trying to maintain a level of joy through that. I lost my mom and, six months later, the pandemic happened.

The work has always been very influenced by the women in my family, the craft work they did. People in my family always made stuff. I never had an understanding of “art” as a kid until I got into high school and a real art class, because it was always just stuff that we did. We were always making stuff. People like my mom, my aunt, my grandparents. And I think that shows too, in the pattern materials.

I think that’s interesting too, incorporating craft and women’s work. Because, I think, the association with metal is with these, like, big burly working men—

Yeah, that’s not true. It’s just perceived that way, in a lot of ways.

There’s a new director at this place called Franconia Sculpture Park, who was speaking of their 30 years of metal work happening at their sculpture as this kind of macho, machismo thing. When, in reality, the metal-casting community that I’m involved in has always been super inclusive. Generally, there is as many, if not more, women involved in all the pours that I have ran and been to over the years, and at that Sculpture Park, there’s a list of hundreds of women who have been and contributed to Park. And, yeah, you get young boys who start casting and it makes them feel like whatever...but as a community, as a whole, it’s a very inclusive community. Everybody’s welcome.

Yeah. The other thing is, trying to incorporate craft, I think there’s a very beautiful sentiment in trying to meld metal and craft, these things that are very gendered.

The machismo, that myth, is what I think is not true. That’s just the patriarchal society that’s been ruining things on the planet for however long it has. And that’s changing, and that’s great.

Now that you say that, I see some of these, especially that one with the hair, as depiction of women?

I think most of my faces are pretty nonbinary. Someone once asked a friend of mine, “So what gender is your sculpture?” (laughs) And she says, “It’s a sculpture!” But then she says, “You’re an a-hole for asking me what gender my sculpture is.” It’s a face. Is it the face of a woman or a man? I don’t know. These are all pretty fluid.

When people make the doodle bowls with Rivers of Steel, do they tend to make faces also? I did when I made mine. Do you think about that at all?

In those workshops, there’s a pretty wide variety of things and subject matters people make. A lady in the last one made a nice bowl with all the zodiac signs. Another made one with ribbons, because her friend had cancer. It’s all over the place with what people make on theirs. I don’t think I’ve seen many faces, though.

You talked a lot about the difficulty of the iron-casting process, that you need a team that really knows what they’re doing. The cool thing to me about the doodle bowls and the Hot Metal Happenings is, it makes these things accessible.

Yeah, the doodle bowl is a really easy way for people to get a glimpse into casting, to take something, make something rad that you can take home. The longer workshops that take longer let people get more creative. Even the ones that ask people to make a sculpture, instead of just scratching a design into a sand bowl, they’re pretty accessible. And they give you good experience. You can do all the jobs in the process, running the furnace. Can you go home and start your own baby furnace? Maybe. But at least you can dip your hands into all parts of the process.

What are the kinds of things that you’d like to do in the future, for the Metal Arts program at Rivers of Steel and your career? What’s next for Ed?

Me, I’m just looking forward to making some new work, continuing what I’m doing now but starting to explore space again, space in installations.

You’re an astronaut.

Traveling the spaceways. Listening to a lot of Sun Ra lately.

But I’m just making work, we’ll see where it goes. I usually work pretty intuitively, I don’t try to have too rigid of a plan going into making the work beforehand. So just taking a minor break, but not really a break, because two days later I’ll be in the basement working on patterns.

And stuff at Carrie, I’d like to sink my teeth into more programming, expanding what we’re doing through workshops, exhibitions, moving into offering some blacksmithing and fabrication. I’ve got this iron class I want to work on to combine the two mediums and bring partners in working both. I’d like to bring more sculpture down to Carrie, rotating like a sculpture park kind of thing. And we’re working on a diversity in metal arts program, to bring in a broader community and make this accessible to everyone.

Labour of Love, featuring Ed Parrish, Jr. & Jack Taylor, will be up at ZYNKA Gallery in Sharpsburg until May 30. You can also catch Ed at Rivers of Steel’s next Doodle Bowl Experience workshop.