The Historic Preservation of the LeMoyne House

Established in 1973 by the National Trust for Historic Preservation, May has been recognized as National Preservation Month for more than fifty years! To help celebrate, Rivers of Steel is sharing the story of LeMoyne House, a National Historic Landmark in Washington, Pennsylvania, which is currently undergoing historic preservation work.

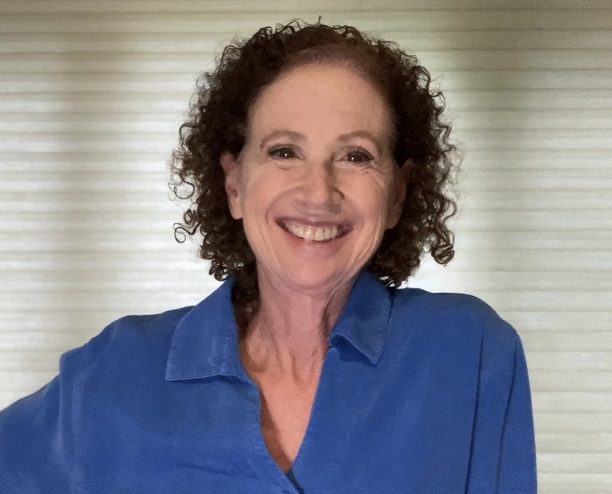

By Julie Silverman, Contributing Writer

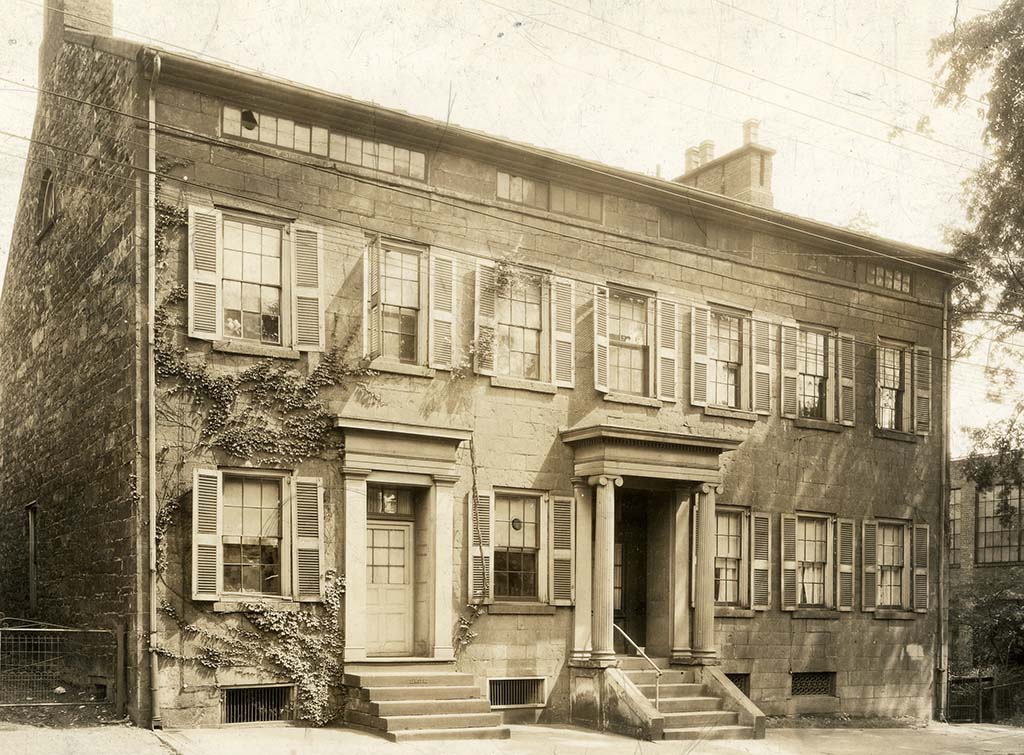

From a Home Built in 1812 to a National Historic Landmark

Shakespeare might have said, “What’s in a name?” but as we celebrate National Historic Preservation Month, we could ask, “What’s in a home?” In Washington County, the LeMoyne House has withstood time and history’s tests for more than 200 years.

Dr. John Julius LeMoyne built the pale stone house on 49 East Maiden Street in Washington, Pennsylvania in 1812. His son, Francis, also a doctor, was a staunch abolitionist who offered his home as a stop along the Underground Railroad. The house was passed down from father to son to daughter, Jane, then Madeleine LeMoyne. When Madeleine passed away in 1943, the house was donated to the Washington County Historical Society (WCHS). In May 1944, the WCHS moved their offices from the third floor of the Washington County Courthouse to the LeMoyne House, which became both offices and museum, opening to the public in the fall of 1944.

With only the LeMoyne family as occupants of the house until 1943, any changes, upkeep, and maintenance were made under the supervision of the family. Eighty years and countless footsteps through the house later have made repairs and preservation vital. There are special challenges for a house that in 1997 received designation as a National Historic Landmark—the first of six Pennsylvania National Historic Landmarks of the Underground Railroad to be registered.

Signage highlights the funders and collaborators in the LeMoyne House’s preservation efforts; image courtesy of WCHS.

A Historic Preservation Begins—and a Story Unfolds

Ellis Schmidlapp is an architect hired by the WCHS’s project manager, the StoneMile Group, to work on the restoration and preservation project. He recommended repairs to the exterior stone and mortar and rebuilding a section of the main front stairs. “For a landmark house that is to be used as a museum, the challenge is to preserve the historic materials and spaces as near to their original appearance and condition as possible,” he said. Attention is also aimed toward “updating mechanical, electrical, and safety systems in a way that is minimally intrusive to the historic character of the building.” WCHS is going to great lengths to preserve and maintain the integrity of the home, retaining its original features and giving it an opportunity to last for centuries to come. Part of the preservation work is handling some older materials that are no longer commonly used, such as “fragile interior finishes of leather, wallpapers, and paint.”

The portico entry steps of the LeMoyne House before preservation work; image courtesy of WCHS.

The portico entry steps during preservation work; image courtesy of WCHS.

As the house receives an uplift, so will the way it tells its story. When the WCHS first opened the home as a museum, they set up displays of family artifacts and papers. Through the years, extended family members have continued to donate items for the collection; however, the visitor experience remained a general exhibit of Washington County history. Sandy Mansmann, current president of the Board of Washington County History and Landmarks Foundation, first saw the LeMoyne House in 1970. “There was lots of old stuff,” she said, “but not much of a story to tell of the depth of the local, and later national, importance of the LeMoynes.”

Beyond preserving artifacts, showcasing key moments of history remain a focus. Clay Kilgore, executive director of WCHS, and Tom Milhollan, director of operations and development, are spearheading an exhibit to highlight the involvement of Francis Julius LeMoyne and others in the Abolitionist Movement and its practical extension, the Underground Railroad.

Washington County Historical Society’s new Research & Education Center; image courtesy of WCHS.

Four years ago, construction began on WCHS’s new Research & Education Center. This effort allowed WCHS’s offices to move out of the LeMoyne House as its center of operations and make the focus the house on the story of the LeMoynes’ place in social reform. While some grants for the house facilitate preserving facades, other grants, including a mini-grant from Rivers of Steel, are bringing to life the Arcs of Freedom exhibition.

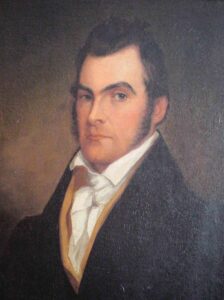

Dr. F. J. LeMoyne’s portrait; image courtesy of WCHS.

Representing The Abolitionist Movement and the Underground Railroad

This project continues the story The LeMoyne House has been telling for decades. In his time, Dr. LeMoyne was a radical abolitionist. He believed not only in ending slavery, but also in the equality and education of enslaved people once they were freed—that all people deserve equal rights. He medically treated Black Americans and was the only doctor in Washington County at the time to do so. But as LeMoyne’s involvement the Abolitionist Movement increased in the 1830s, he began to realize that it would not be enough to simply talk about abolition, and that more practical steps would be necessary.

Building on the story of Dr. LeMoyne, Tom said, “The Abolitionist Movement and the Underground Railroad represented the convergence of a lot of different people coming from different racial backgrounds, different social backgrounds, different economic backgrounds, different religious denominations—all coming together for the common purpose of defeating slavery.”

Arcs of Freedom, the upcoming interpretive project, will add previously hidden pieces. “We want to tell the story of the Abolitionist Movement and the Underground Railroad through the eyes of the participants—first and foremost, through the freedom seekers themselves,” Tom said. These are the stories that have been forgotten. This new exhibit seeks to preserve stories of the free Black community that had been bypassed. “We feel that history has been kind of slanted to where freedom seekers were totally dependent on wealthy white benefactors to take them to freedom, and that is an incorrect narrative.”

Tom said, “The African American Underground Railroad conductors helped build that movement.” Clay adds, “We had an artist from Washington & Jefferson College—a student there—who obtained photographs of the descendants of one of the freedom seekers and made a composite of what this freedom seeker might have looked like. We’re going to add faces to names—names that people really don’t know. Now, not only are they going to get the name, but they’re going to get the face to it.” For example, this professionally designed exhibit will feature people such as George Walls, who was one of the most prolific African American Underground Railroad operatives in this area. Photographic images and even key details of his life were missing; however, with a bit of luck they found a newspaper interview with him and were then able to find photographs of his descendants.

“We’re interacting with a descendant of one of George Walls’s brothers,” Clay said. “Her name is Lorraine Walls Perry—she lives in Pittsburgh and is a member of our steering committee for this exhibit. She has been really helpful in us understanding the whole enterprise from the perspective of the African American operative. Lorraine, herself, is not only a descendant of an Underground Railroad operative, but she’s also a descendant of a freedom seeker on the Underground Railroad by the name of Alfred Crockett. We have put tremendous effort into uncovering obscured resources—resources that were previously hidden from common view. And we’re trying to bring all of that information to the foreground in this exhibit.”

Dr. F. J. LeMoyne’s Philanthropy

Francis Julius LeMoyne was less visible in the movement after 1850. He suffered from arthritis, and travel was increasingly painful. At this point in his life, he refocused most of his efforts on philanthropy and other social reform causes. His activities emphasized his interest in education and included establishing Washington’s first public library, currently known as Citizen’s Library. During the Civil War, he donated money to Washington College, keeping it from bankruptcy and ensuring that education continued for those who returned home. He donated $20,000 to a small seminary in Memphis, Tennessee, so that many newly freed people could go to school; it’s called LeMoyne-Owen College, even though he requested that his name be withheld. As early as 1835, he started the Washington Female Seminary so that girls, including his own daughters, could receive an equal education. (At that time, the norm was that boys went to academy, and girls studied at home.)

Dr. F. J. LeMoyne’s crematory; image courtesy of the WCHS.

In 1876, LeMoyne again challenged the norm by creating the LeMoyne Crematory—the first crematory in the United States and only the second in the world. He believed that cremating human remains would be more advantageous to health and sanitary conditions. He built the crematory on his own land just outside of Washington, Pennsylvania. Restoration was completed in 2020, and the LeMoyne Crematory is now also part of WCHS and listed on the National Register of Historic Places.

A historic image of the LeMoyne House; image courtesy of WCHS.

Connecting the Past to the Present

Historic homes allow unique insights into a specific era. The LeMoyne House, from its inception in 1812, has been both stage and witness to history. “It has seen the construction of the National Road,” Clay said. “It has seen freedom seekers come in and out. It has seen abolitionists come here and speak. It has seen women’s suffrage movements and Susan B. Anthony here in this house. It has seen the Civil Rights Movement through the movements of today. We want to weave an entire story that tells not only of the LeMoynes, but of the struggles that people have had and how everything here fits into it—how the movements of today tie to the Underground Railroad and the Abolitionist Movements of the past.”

The LeMoyne House in Washington, Pennsylvania, intertwines the articles of the house and the history of Dr. LeMoyne himself, with the context, circumstances, and rich heritage of the Western Pennsylvania region. It was honored with a competitive grant from the National Park Service’s History of Equal Rights grant program for which ten historic sites were selected in support of their preservation work and historical connection with advancing civil rights.

“Saving and restoring the house is a valuable resource to tell this story, even with its creaks, groans, and smells. The structure definitely has outgrown its capacity to effectively house and maintain historic county records and documents. Its return as a primary history museum is most welcome. Its renewal and the construction of an adjacent center for research and document storage will once again revive the interest of continuing generations to visit and appreciate the legacy of Washington as a center of our heritage,” said Sandy Mansmann.

To read more about the LeMoyne House and its role in the Underground Railroad, read this contribution by the Washington County Historical Society from this past February.

Julie Silverman is a museum educator, tour facilitator, and storyteller of astronomy and history for various Pittsburgh area organizations, including Rivers of Steel. A Chatham University 2020 MFA graduate, her writing is most often found under the by-line of JL Silverman. Occasionally, under the name of Julia, she has been seen on TV.