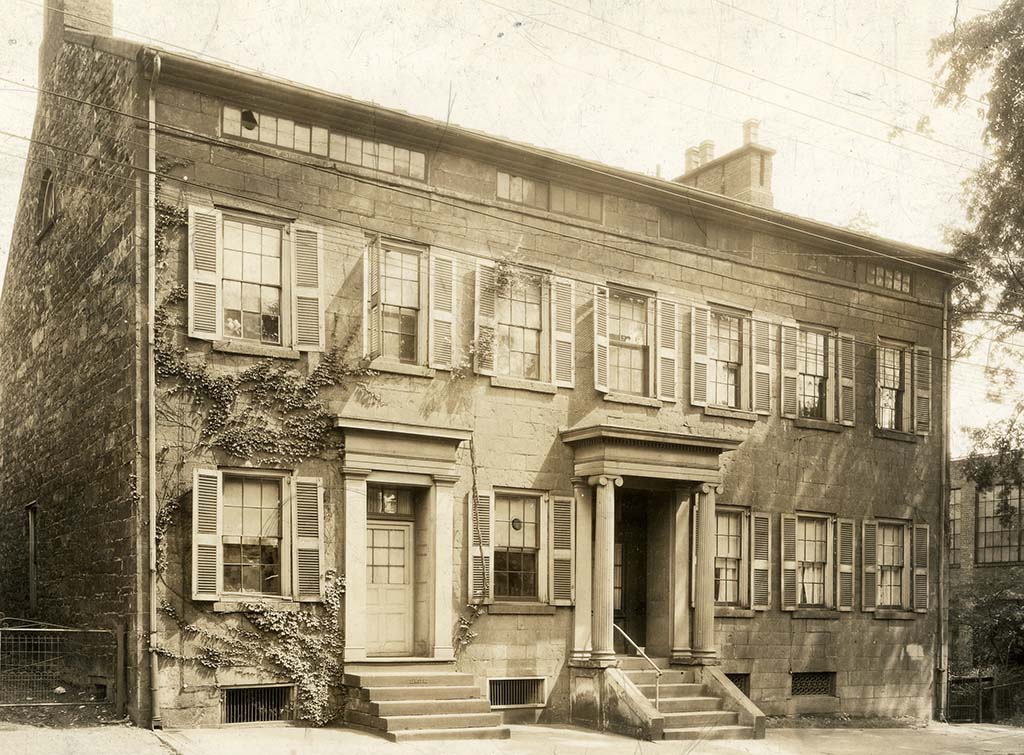

Washington County Historical Society’s LeMoyne House represents an important part of southwestern Pennsylvania’s rich history. The National Park Service states that the LeMoyne House is one of six NPS-recognized Underground Railroad sites in Pennsylvania—and it is the only one of these six located west of the Allegheny Mountains.

The Underground Railroad in Southwestern Pennsylvania

Guest Contribution by Washington County Historical Society

Every year, Black History Month invites us to view the tapestry of American history a little differently— through the lens of the African-American experience. While we rightly celebrate Black excellence in familiar fields—from business and academia to the arts, sports, and modern era civil rights activism—it also offers an occasion to explore lesser known stories. One such narrative is the pivotal role African Americans played in the formation of our nation’s first civil rights movement: abolitionism and its practical arm—the Underground Railroad.

Free Black Communities, Religion, and the Origins of the Underground Railroad

In the decade following the War of 1812, free Black communities began to lay the tracks of what later became the Underground Railroad. To understand how these communities helped initiate the Underground Railroad in southwestern Pennsylvania, one must look back to colonial times. Settlers from Maryland and Virginia brought enslaved individuals to the region, and while slavery did not take root as firmly in Pennsylvania as in other colonies, its presence loomed large, particularly in pre-revolutionary Westmoreland County (from which the counties of Washington, Fayette, Allegheny, Somerset, and Greene were later formed). In this way, African Americans were among the earliest settlers and contributed significantly to the early economic growth of the area.

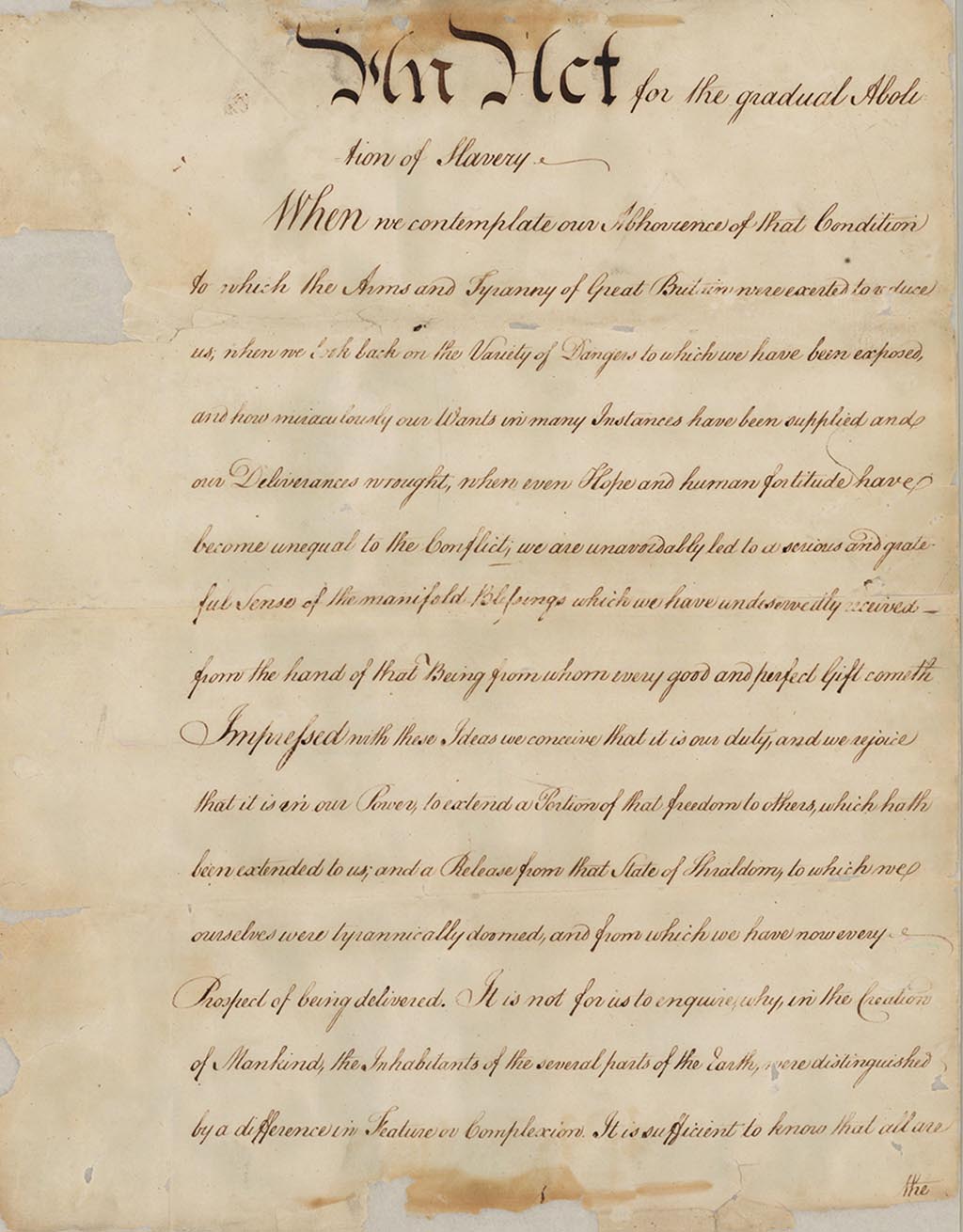

Act for the Gradual Abolition of Slavery

The Pennsylvania General Assembly’s “Act for the Gradual Abolition of Slavery” was adopted in 1780.

The age of slavery in Pennsylvania began to recede in 1780 with the passage of the “Act for the Gradual Abolition of Slavery,” heralding a new era of hope for enslaved African Americans. Though not an immediate emancipation decree, the Act ensured that future generations would be born into freedom, marking a significant step toward the eventual abolition of slavery in Pennsylvania. Children born after the passage of the Act became the first generation to gain full freedom in the years prior to the War of 1812. Additionally, some enslaved people born prior to the Act’s adoption would ultimately attain their freedom in Pennsylvania through individual emancipations or through legal challenges of an enslaver’s compliance with the Act. Thus, painfully slow as it was, slavery’s ultimate demise in Pennsylvania was set into motion.

Religion Aides Community Organization

Religion had served as a cornerstone of Black communities, offering solace and solidarity amidst the trials of slavery. During the 1780s, Baptist and Methodist churches began to draw the religious interest of many African Americans. As years passed, especially within Methodism, unresolved issues of slavery and inequality began to divide some of these congregations—and Black congregants began considering alternatives. In Philadelphia, the first African Americans left St. George’s Methodist Church in 1787 to form independent congregations offering a path to spiritual autonomy and equality. One of these became Mother Bethel African Methodist Episcopal Church, founded by Rev. Richard Allen in 1794. By 1816, Rev. Allen and others led the formation of the African Methodist Episcopal Church conference as an entirely independent denomination. Within a few short years, the influence of this new A.M.E. denomination grew and attracted attention in southwestern Pennsylvania.

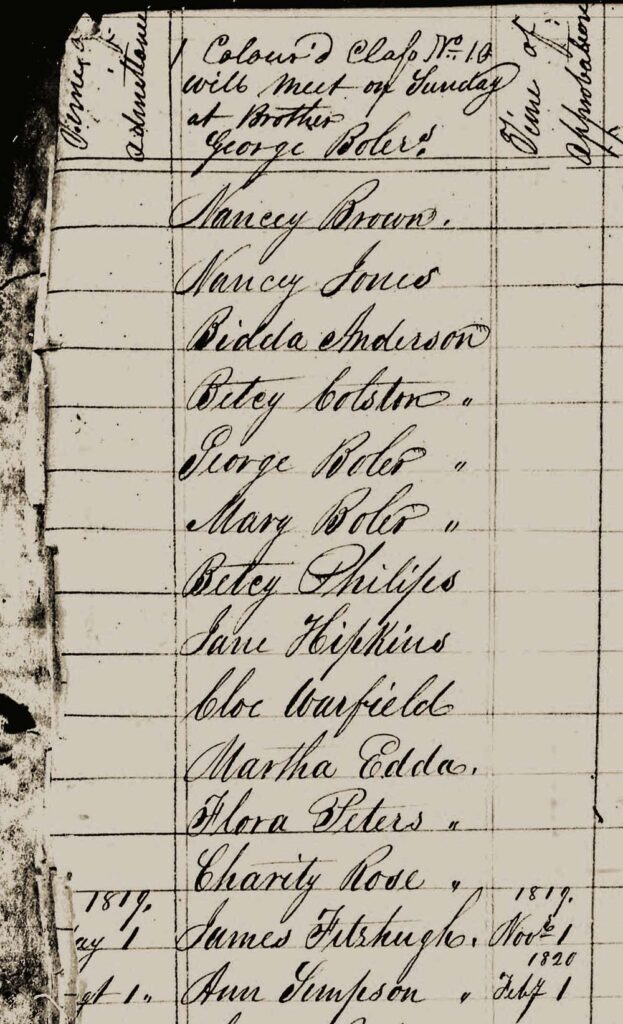

In Washington County, a local Black barber and Methodist class leader named George Boler wrote to A.M.E. leaders in Philadelphia in 1818 requesting support in formating a new Black congregation in Washington, PA. Rev. David Smith of the A.M.E. church came west in 1820 to help Boler complete this effort. With Rev. Smith’s support, George Boler led a concerted exodus of Black congregants out of the First Methodist Episcopal Church in Washington and into a new society that would later become St. Paul African Methodist Episcopal Church.

“I then proceeded to open the doors of the (new) Church, and forty-eight persons came forward and joined the A.M.E. Connection.” – Rev. David Smith on founding the A.M.E. church in Washington, PA. – Biography of Rev. David Smith of the A.M.E. church, 1881.

As members of the First Methodist Episcopal Church in Washington, PA, George Boler, Benjamin Dorsey, Betcy Philips, Cloe Warfield, and others formed a new society between 1818 and 1820 that would later become St. Paul African Methodist Episcopal Church.

Rev. David Smith and George Boler soon replicated their success in Washington by helping establish new A.M.E. churches in Brownsville and Uniontown. In other towns along the National Road and elsewhere in the region, new Black congregations were founded within the A.M.E. and A.M.E. Zion denominations. Ties among congregants and between congregations strengthened in the region. Trusted networks were formed. These networks served a dual purpose: not only did they support the congregants and their churches, but they also provided aid to those in dire need—freedom seekers making their way into southwestern Pennsylvania from the depths of slavery in Maryland or Virginia, as well as those who escaped while in transit on the National Road.

By the late 1820s, these networks, anchored by religious ties, became a lifeline for freedom seekers. They offered more than just spiritual support; they provided practical assistance such as meals, places to rest, and guidance to the next safe house. As the 1830s unfolded, radical white abolitionists in the region, including Dr. Francis Julius LeMoyne of Washington, PA, grew increasingly frustrated with the limitations of their efforts to combat slavery through “moral suasion” and shifted their focus to a more pragmatic form of abolition—direct aid to freedom seekers. Through this collaboration across traditional racial, social, and religious divides, the “friends of freedom” formed a broader decentralized network dedicated to helping those seeking liberty. This collective effort against slavery, characterized by everyday acts of kindness and occasional acts of heroism, would become the Underground Railroad in southwestern Pennsylvania.

The upcoming exhibit entitled Arcs of Freedom, to be completed by the Washington County Historical Society later this year, offers an opportunity to explore the story of the Underground Railroad in southwestern Pennsylvania. Through primary funding from the National Park Service’s Network to Freedom program and the Rivers of Steel mini-grant program, the exhibit seeks to remember the voices of all those involved in the movement, including the freedom seekers themselves. In commemorating their courage and resilience, Arcs of Freedom invites us to reflect on the enduring legacy of the Underground Railroad and its indelible impact on our region’s history.

The LeMoyne House today.

An Underground Railroad tour group learns about the activities that happened in and around the LeMoyne House, a National Historic Landmark in Washington, Pennsylvania.

All images are courtesy of the Washington County Historical Society.

About the Washington County Historical Society and the Arcs of Freedom Exhibit

The Washington County Historical Society (WCHS) is a center for preservation, research, and education that inspires the discovery and sharing of Washington County’s remarkable history. Central to this mission is WCHS’s administration of the historic Dr. Francis Julius LeMoyne House, an enduring beacon of freedom and social reform, for the benefit of the public.

The LeMoyne House, constructed in 1812, is a National Historic Landmark and a site on the National Park Service’s National Underground Railroad Network to Freedom. The upcoming Arcs of Freedom exhibit, created by WCHS under its Waller-McDonald Collection of African American History, will be presented at the LeMoyne House. WCHS is grateful for the efforts of the Arcs of Freedom steering committee that includes historian and author Dr. W. Thomas Mainwaring, historian and author Marlene Bransom, freedom seeker descendant and author Lorraine Walls-Perry, and others.

Inquiries about WCHS, the LeMoyne House, the Arcs of Freedom exhibit, and the Network to Freedom program may be directed to Tom Milhollan, Director of Operations & Development for WCHS, where he also leads WCHS’s study of the Abolitionist Movement and the Underground Railroad.