By Brianna Horan, Manager of Tourism & Visitor Experience

Routes to Roots!

Routes to Roots!

You might be a Pittsburgher, a Monacan, a Vandergrifter, a Farmingtonian, or a Rices Landing resident. But if you live in the southwestern corner of Pennsylvania, you can also feel proud that you’re from the Rivers of Steel National Heritage Area.

A National Heritage Area is designated by Congress as a place of significance to America where natural, cultural, and historic resources highlight an important period of history in the development of the United States. The Rivers of Steel National Heritage Area draws its strength from the region’s industrial history, the landscape that fueled it, and the hardworking men and women who made it possible. The eight counties—and the hundreds of cities, small towns and main streets within them—that form the heritage area are linked not only by their river valleys, but by their shared cultural and industrial heritage through five journeys that each reveal an element of the region’s legacy as the Steel Capital of the World for more than a century.

The historical sites, cultural attractions, family-owned restaurants, mom-and-pop shops, and natural beauty that tell the story of these journeys also combine to make a fantastic travel itinerary filled with meaningful and memorable experiences. That’s why heritage tourism is a key component of Rivers of Steel’s mission. Defined by the National Trust for Historic Preservation as “traveling to experience the places, artifacts, and activities that authentically represent the stories and people of the past and present,” heritage tourism immerses travelers into the roots of culture and shows them how the past lives on in modern ways.

In celebration of National Travel and Tourism Week, below is a description of each of the journeys in the Rivers of Steel National Heritage Area—along with a few sites in each that resonate with the themes of Big Steel’s industrial and cultural heritage. Much of this information is sourced from Routes to Roots, a driving guide published by Rivers of Steel that is available in the Bost Building’s gift shop.

To protect yourself and others and to reduce the spread of COVID-19, it is important to limit your travel to essential activities only during this time. Additionally, many businesses and sites are closed because of the pandemic. Please enjoy the sites below as an armchair traveler for now—they all tap historical topics that make for great reading until it’s safe and permissible to travel again. Don’t forget to bookmark this page for your list of “Things to Do When Quarantine is Over!”

The Big Steel Journey | Allegheny County

The Big Steel Journey recaptures the dynamic era when the city’s steel empire was the backbone of the nation’s industrial economy, building the modern world. Thousands of immigrants were drawn to the promise of jobs, and they would go on to produce millions of tons of steel that built the Empire State Building, the Bay Bridge, the St. Louis Arch, and the battleships and tanks that won two World Wars. The industrial core was the Monongahela River’s Steel Valley, where U.S. Steel’s massive mills and furnaces dominated both sides of the river for more than ten miles, and 18 contiguous communities on the lower Mon.

The industrial power and astonishing work ethic drew awe and respect from visitors as long ago as 1868 —five years before Andrew Carnegie started construction on his first mill, when James Parton wrote a 13,000-word travelogue of his visit to “Pittsburg” (we’d been separated from our “H” at the time) for The Atlantic. He was quite taken with the city, starting off the article, “In other towns the traveler can make up his list of lions, do them in a few hours, and go away satisfied; but here all is curious or wonderful, — site, environs, history, geology, business, aspect, atmosphere, customs, everything. Pittsburg is a place to read up for, to unpack your trunk and settle down at, to make excursions from, and to study as you would study a group of sciences. To know Pittsburg thoroughly is a liberal education in “the kind of culture demanded by modern-times.” It’s hard to believe that this is the same article that earned the city the moniker of “hell with the lid taken off,” but in reality he was describing the view from the Hill District overlooking the smoky, fiery, bellowing nighttime skies of the Strip District as “a spectacle as striking as Niagara.”

There are a number of Rivers of Steel sites in Allegheny County that tell the story of Big Steel and the men, women and communities that fueled it. We’d love to welcome you at all of them! Here are a few more ways to connect with the Big Steel Journey:

Flex your muscles in front of the 15-foot-tall statue of Joe Magarac bending a rod of steel in front of U.S. Steel’s Edgar Thompson Works in Braddock. Magarac is a legend of the steel industry akin to Paul Bunyan, symbolizing the impossibly hardworking mill workers. If you visited Kennywood Park before 2009, you might remember seeing this statue there. The mill behind it is also a site to be seen—the only remaining integrated steel mill the state, Edgar Thompson, a.k.a E.T., was Andrew Carnegie’s first mill, and has been active since 1875. Want more Magarac? Iron Eden, a Pittsburgh blacksmithing studio known for ornamental ironwork, operates a gallery and gathering space bearing his name. MAGARAC has an industrial vibe and is furnished and decorated with Iron Eden’s Magarac line of ironwork; the gallery is open by appointment.

Flex your muscles in front of the 15-foot-tall statue of Joe Magarac bending a rod of steel in front of U.S. Steel’s Edgar Thompson Works in Braddock. Magarac is a legend of the steel industry akin to Paul Bunyan, symbolizing the impossibly hardworking mill workers. If you visited Kennywood Park before 2009, you might remember seeing this statue there. The mill behind it is also a site to be seen—the only remaining integrated steel mill the state, Edgar Thompson, a.k.a E.T., was Andrew Carnegie’s first mill, and has been active since 1875. Want more Magarac? Iron Eden, a Pittsburgh blacksmithing studio known for ornamental ironwork, operates a gallery and gathering space bearing his name. MAGARAC has an industrial vibe and is furnished and decorated with Iron Eden’s Magarac line of ironwork; the gallery is open by appointment.

- The Energy Innovation Center (EIC) isn’t too far from Cliff Street, the spot that The Atlantic article suggested for views of “hell with the lid taken off.” (Cliff Street is just a block behind the August Wilson House). The EIC is housed in the former Connelley Trade School, which was built in 1930 in The Hill District because its altitude put it above much of the air pollution that clogged the city, and because it was well connected to other areas by trolley and Union Station. Once a place where students learned bricklaying, plastering, plumbing, auto mechanics, electrical wiring, carpentry, cabinetry, and more—today it has been reborn as a LEED Platinum certified National Historic Landmark that is a “living laboratory” for industry-informed education and training programs, housing STEM industry leaders and offering job readiness training. For a similar feel with a rooftop bar, check out the new TRYP in Lawrenceville, a boutique hotel in the historic former Washington Education Center, where men learned bricklaying, woodworking, drafting and metal work. Elements of the original structure are at the core of the building’s design, and Over Eden restaurant and bar on the rooftop has incredible skyline views of Downtown while overlooking former steel sites like Bay 41 at the Foundry and the National Robotics Engineering Center.

- If you’re speeding past on Fort Duquesne Blvd., you might not have noticed that the mural painted on the side of the Byham Theater downtown depicts scenes from the region’s history as a Steel Town. The Pittsburgh Cultural Trust selected renowned American muralist Richard Haas to create the Trompe l’oeil mural in 1993. Take a walk downtown to get a good look.

- The McKeesport Regional History & Heritage Center celebrates its 40th anniversary this year. The Center houses the City of McKeesport’s first schoolhouse, built in 1832, and has displays featuring McKeesport and the Mon Valley’s history, including an Industry Wing with a large-scale model of the U.S. Steel National Tube, church collections, and an exhibit honoring Helen Richey, the first licensed female commercial pilot who helped to create an airmail system.

- George Westinghouse was an engineer who received 360 patents for his work, founded 60 companies, and invented things like the railway air brake, nuclear reactors, and alternating current. Residents of Chalfont are familiar with the Westinghouse Atom Smasher, looking like a large, upside-down silver lightbulb. The world’s first industrial Van de Graaf generator was created by Westinghouse Labs in 1937 (after Westinghouse’s 1914 death), and while the lab is no longer there, the atom smasher is resting on its side in an overgrown parking lot on Service Rd. No. 1, across the street from Tugboat’s Restaurant and Bar at 105 West St., East Pittsburgh, PA 15112. You might also want to take a stroll in Westinghouse Park in Point Breeze, built on the land where Westinghouse’s estate and home laboratory once stood. It’s thought that his underground labs may still be intact!

Thunder of Protest | Beaver County

Southwestern Pennsylvania’s people are known for strong values and deeply held beliefs—something that is evident in more than 200 years of history along the Ohio and Beaver Rivers where the communities have shown a willingness to take a stand. For hundreds of years, the Ohio-Beaver riverfronts were a Native American trading area. The region’s first century of European settlement was strongly influenced by the Harmony Society, German Protestant religious dissidents who were also successful industrial entrepreneurs. Their industrial pursuits included some of southwestern Pennsylvania’s earliest iron foundries and rolling mills. Due in large part to the Harmonists’ early ventures, iron production prompted the growth of a string of towns along the Beaver River. A sect of the Harmonists broke away in the 1800s, disagreeing with lifelong commitment to celibacy that was part of the societies’ practices, to build towns on the other side of the Ohio River.

The second century of the area’s development were shaped by iron and steel. The town of Ambridge, started by the American Bridge Company, was built on property purchased from the Harmonists. Across the river, the Jones & Laughlin Steel Company (J&L) built southwestern Pennsylvania’s largest basic steel mill complex, the Aliquippa Works, in 1900. Thousands of immigrants from eastern and southern Europe, along with African Americans from the south, flocked to the area to work in these new mills. The Ohio-Beaver area soon became divided between the management who lived in fine homes in Beaver, far away from the cramped milltown workers’ quarters. Fearing labor unrest and trying to keep production high and costs low, J&L kept tight control over its facilities and workforce. In Aliquippa, J&L required workers to live in company-built neighborhoods segregated by ethnicity, with round-the-clock surveillance by company police and strictly enforced curfews. Things came to a head in 1937 in an uprising that challenged J&L’s policies, resulting in the 1937 Little Steel Strike.

Old Economy Village tells the story of the Harmony Society, one of the oldest and most successful religious communal groups of the 19th They sought to create a utopia inhabited by German Lutheran separatists who subscribed to the mystical religious teachings of their leader George Rapp (1757 – 1847). They created a self-sustaining village with agriculture, blacksmithing, tanning, cabinetmakers, and textile mills powered by steam engines. Their Economy was successful, and they sold their products throughout the world. Ultimately their belief in celibacy spelled out the end of the society by 1905. Old Economy Village features 17 authentic Harmonist buildings, gardens, streets and artifacts on six serene acres in Ambridge.

Old Economy Village tells the story of the Harmony Society, one of the oldest and most successful religious communal groups of the 19th They sought to create a utopia inhabited by German Lutheran separatists who subscribed to the mystical religious teachings of their leader George Rapp (1757 – 1847). They created a self-sustaining village with agriculture, blacksmithing, tanning, cabinetmakers, and textile mills powered by steam engines. Their Economy was successful, and they sold their products throughout the world. Ultimately their belief in celibacy spelled out the end of the society by 1905. Old Economy Village features 17 authentic Harmonist buildings, gardens, streets and artifacts on six serene acres in Ambridge.

- Built in 1910 to create an entrance to the J&L Steel Company’s Aliquippa Works beneath the Pittsburgh & Lake Erie Railroad tracks, the Tunnel was the way that the mill’s 15,000 workers came to work every day. In May of 1937, shortly after the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that employers must bargain in good faith with union representatives, talks between the Steel Workers’ Organizing Committee (SWOC) and J&L were getting nowhere. When the union voted to strike on May 12, the Tunnel became the staging ground for thousands of workers leading up to the 11 p.m. shift change. As May 13 dawned, only a few hundred workers remained in the mill, and the possibility of serious violence was imminent. The next day, Gov. George Earle arrived to tour the Works, and then urged the parties to negotiate a peaceful settlement. Later that day, J&L agreed to recognize union elections, and a new contract was signed. Today the Tunnel still stands as the entry to the Aliquippa Industrial Park, with a Workers’ Shrine To get there, follow Franklin Ave. underneath Constitution Blvd. until it becomes Station Street. After your visit, take a drive through one of the housing plans to see the scale of J&L’s company control.

- Nearby to the Tunnel is the B.F. Jones Memorial Library, built in 1929 by Elisabeth Horne to honor her father, Benjamin Franklin Jones, Sr., co-founder of Jones & Laughlin Steel. Elisabeth saw it as an opportunity to serve the educational and cultural needs of the white-collar managers and immigrant laborers who settled in Aliquippa. The ornate 15,000-sq. ft. facility was designed in a restrained Italian-Renaissance style.

- Edward Dempster Merrick made his money as an industrialist at his family’s Standard Horse Nail Company, but his passion for art would define his life and legacy. He wasn’t permitted to pursue art as a child, but as Merrick approached his 50th birthday he began buying paintings, particularly those of the Hudson River School, and painting his own works. In 1880, he founded the Merrick Free Art Gallery and Public Library. He became an eccentric collector and creator, and his gallery is still open to the public in New Brighton. Down the street, the Merrick family’s Standard Horse Nail Company still stands in a building dating from the mid-1880s, as well – these days they make precision parts.

Mosaic of Industry | Allegheny, Armstrong, Butler, and Westmoreland Counties

The variety of industrial work is matched by the diverse cultural heritage of the region. During the 18th century, early European fur trappers and explorers encountered Seneca and Delaware villages along the Allegheny River from Kittanning southward as Scots-Irish, German, and English settlers began to stake out farmsteads. After the Revolutionary War, the pace of European settlement quickened. Originally agricultural, the area soon began to attract workers for its burgeoning industries—especially after the opening of the Pennsylvania Canal and the rise of “Big Steel” in the region. By the late 19th century, the Alle-Kiski area was home to many eastern Europeans, as well as Italians and African-Americans. German settlers settled in Butler’s Harmony village, in what was a precursor to the Economy settlement in Ambridge. Today, the cooking traditions, sacred spaces, dances, and music create a rich tapestry of cultural experience for visitors.

- At the Rachel Carson Homestead in Springdale, visitors can tour Carson’s childhood home, where she could see the Allegheny River from her window while heavy industry came into its own all around her. A graduate of the Pennsylvania College for Women (now Chatham University), Rachel Carson’s work and writing created the modern environmentalist movement and led to the outlawing of DDT pesticides. Her modest childhood home in Springdale was just downriver from a DDT manufacturing plant.

- At the Tour-Ed Mine & Museum in Tarentum, visitors ride in trams through the former Avenue Mine that formerly served as a source of raw materials for Allegheny Ludlum Steel. In 1964, the Wood Coal Company took over operations, and for the next six years it supplied coal to local businesses like Tarentum Power and PPG. In 1970, operations changed when owner Ira Wood decided to use the mine to preserve the culture, the tools—the life—of the men who once worked there. Former miners are the tour’s docents, who talk about the coal industry, the mining process, and the workers’ culture.

- Timing is everything. That was certainly the case for the builders of Mount Saint Peter Roman Catholic Church in New Kensington. In 1941 as the grand Richard Beatty Mellon Mansion in Pittsburgh was being demolished, Mt. St. Peter was being constructed. A longtime Mellon employee and friend to the Kew Kensington Italian Community saw the opportunity to reuse the Mellon’s finery in the new church. The parish’s Italian congregants mostly worked in the nearby Alcoa plant, but in their native land they had been stonemasons, carpenters, and metalsmiths. They set out to transform the Mellon mansion’s porch banister into the communion rail, a chandelier was reconfigured into the baptismal front, and former library doors now surround the confessionals. Antonio Muto spent more than six months on his knees, cutting and piecing together marble to form an intricate pattern on the basement floor. There is even a red Verona marble pulpit that was commissioned by Andrew Carnegie, along with a 19th century painting, Behold the Lamb of God, that once hung in the Vatican and then in the original Heinz Chapel on the North Side.

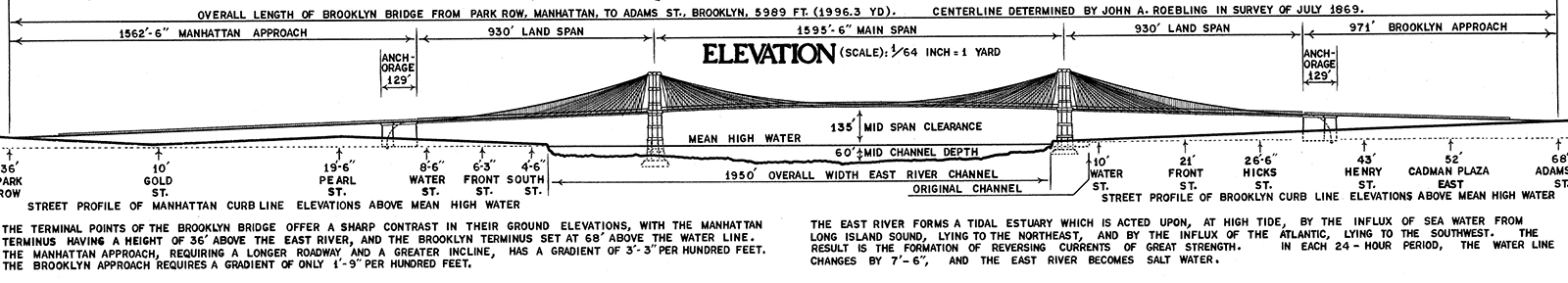

- Great strength can be found at the Saxonburg Museum, which includes the Roebling Workshop. Saxonburg was founded by John Roebling, a German immigrant who invented wire cables in this workshop. He went on to design the Brooklyn Bridge, putting his suspension cables to good use. There’s a small replica of the Brooklyn Bridge onsite! In addition to a history of the Roeblings, the Saxonburg Museum features exhibits on communications, blacksmithing, a general store, and laundry practices.

- Before Economy, there was Harmony. This small Butler County town was founded in 1804 by 90 families who followed religious leader George Rapp away from the official Lutheran Church and out of Germany. Learn more about their way of life – in addition to 250 years of history – at the Harmony Museum.

Whereas some parts of the Rivers of Steel National Heritage Area were dominated by one industry, such as steel or coal, the Mosaic of Industry Journey boasts an array of businesses and crafts that were connected to or influenced by steel. Aluminum, plate glass, refractory brick making, foundries, limestone quarries – all flourished here. Salt extraction methods developed here led to the first oil drilling. And, of course, there were steel mills and coal mines as well. Many of the companies with large-scale plants in the area, such as Alcoa (formerly Aluminum Company of America) and PPG Industries (formerly Pittsburgh Plate Glass) are household names throughout the United States.

Mountains of Fire | Westmoreland and Fayette County

For most of a century, hundreds of beehive ovens burned day and night across the hills and valleys of Fayette and Westmoreland Counties. Today the landscape charms with green rolling hills, but at one time this is where coal was transformed into coke, the fuel for steelmaking. These “Mountains of Fire” produced millions of tons of the highest quality coke to power the steel mills throughout the Pittsburgh industrial district, and coal mining and coke production came to define and dominate this part of the region. It reshaped and expanded older farming communities like Uniontown. It created scores of company-built patch settlements like Morewood, Leisenring, Bessemer, and Indian Head. It also spurred the growth of other industries, such as glassmaking and railroads. Henry Clay Frick rose from this region as the coke king, going on to become the partner of Andrew Carnegie in the Carnegie Steel Company.

- The Westmoreland Museum of American Art overlooks the city of Greensburg’s main street. Two of the museum’s regional collections, Southwestern Pennsylvania Landscapes and Valley of Work: Scenes of Industry vividly portray the evolution of this region’s landscape from rural farmland to a nighty industrial concept. The stunning “before and after” view of the region draws a stark contrast.

- The Saint Vincent Grist Mill and General Store are cornerstones of Saint Vincent College. Visitors can watch the gristmill in action and purchase bags of Saint Vincent’s own whole wheat flour, made by the 185 monks who live at the Saint Vincent Archabbey—the first Benedictine order in the United States. When the three-story mill was built in 1854, it was originally powered by a coal furnace, stoked by the monks who mined their own coal. Electrification came in 1952, and in the early 1990s the Monastery Run Project effectively treated the abandoned mine drainage that followed the decline of the local mining industry.

- Meaning is everywhere at The Ruins Project in Perryopolis, where mosaicist Rachel Sager tells forgotten stories with raw materials. An outdoor experience close to the banks of the Youghiogheny River and the Great Allegheny Passage bike trail, a masterpiece of mosaic art has come to life on the walls of an abandoned coal mine banning, representing the rebirth of abandoned American coal country into a spiritual and artistic pilgrimage and destination for adventure seekers and lovers of art and history.

The rural setting of West Overton Village & Museums was the birthplace of Old Overholt Whiskey and Henry Clay Frick. With eighteen original buildings, West Overton is a charming pre-Civil War village. With distillery tours and tastings, homestead tours, and demonstrations of the backbreaking work that made this village self-sufficient, a visit to West Overton is a visit to the past. Frick was always looking towards the future, however. As he grew older, his grandfather paid him to keep the books for the distillery. Recognizing that the region was rich in bituminous coal deposits, Frick formed his own company and began buying land, building coke ovens, and making a lot of money. By his early 30s he was a millionaire living in Pittsburgh with his bride, Adelaide Howard Childs, at Clayton. His H.C. Frick Coke Company became the largest producer in the world, and Frick became the business partner—and then enemy—of Andrew Carnegie.

The rural setting of West Overton Village & Museums was the birthplace of Old Overholt Whiskey and Henry Clay Frick. With eighteen original buildings, West Overton is a charming pre-Civil War village. With distillery tours and tastings, homestead tours, and demonstrations of the backbreaking work that made this village self-sufficient, a visit to West Overton is a visit to the past. Frick was always looking towards the future, however. As he grew older, his grandfather paid him to keep the books for the distillery. Recognizing that the region was rich in bituminous coal deposits, Frick formed his own company and began buying land, building coke ovens, and making a lot of money. By his early 30s he was a millionaire living in Pittsburgh with his bride, Adelaide Howard Childs, at Clayton. His H.C. Frick Coke Company became the largest producer in the world, and Frick became the business partner—and then enemy—of Andrew Carnegie.

- At the Coal and Coke Heritage Center at Penn State’s Fayette Campus in Uniontown, the soul of the coal patches and is on display in the displays of artifacts, tools, gear, home goods, and oral histories of miners and their families. In Farmington, the well-preserved, limestone Wharton Furnace stands tall as an example of the iron-smelting furnaces that dotted the early 19th-century landscape in southwestern Pennsylvania. This one was used from 1839 – 1873. And near a lake in Mt. Pleasant’s Mammoth Park, visitors can explore a row of preserved beehive ovens and two narrow-gauge “larry” cars.

Fueling a Revolution | Greene and Washington Counties

Once hailed as the “hardest working river in the world,” the Monongahela runs north from its origins in West Virginia into the Pittsburgh region. For more than a century, the Mon has carried millions of tons of high-quality bituminous coal to power southwestern Pennsylvania’s steel mills and electrical generation plants—the fuel for America’s Industrial Revolution. Along the way, the river offers breathtaking views and enjoyable pastimes like fishing and boating, and the fleets of barges that still ply its waters today speak to the river’s long history as the steel era’s most vital industrial artery.

Early in the 20th century, as by-product coke production replaced the older beehive method, the Mon became indispensable for transporting raw coal from the mines to the processing plants. The river’s system of locks and dams was built to facilitate the transportation of coal, and the coal companies’ riverside barge loading facilities, as well as river-related industries such as barge building and repair, provided employment for many.

- The Donora Smog Museum is operated by the town’s historical society, and it maintains permanent exhibits related to the founding of the town, town life, steel mills, and the 1948 smog tragedy. In 1948, two large plants dominated Donora—the U.S. Steel Donora Zinc Works and the American Steel & Wire plant. Just before Halloween of 1948, a dense haze blanketed the town that wouldn’t blow away. A temperature inversion in the valley trapped the noxious emissions from the two plants, and soon residents began to fall ill. Five days later a rainstorm helped to clear out the smog, but not before roughly half of the town’s population of 14,000 became sick and 20 had died. Fifty more people died soon after the smog lifted. While in town, take a drive around Cement City, a company town built by Union Steel Company in 1916 to create housing for workers. A building concept that was the notion of inventor Thomas A. Edison, 80 homes were completed overlooking the mill. Rent ranged from $22.50 to $40. Drive around Walnut, Modisette, Ida, Bertha and Helen Streets in Donora.

- The Flatiron Heritage Center in Brownsville stands in a building that over the years has housed ethnic banks, taxi services, a trolley stop, and a number of different tailors, as well as the original Brownsville library and post office. In the Flatiron Building’s first floor, visitors learn from exhibits about Brownsville’s colonial past, sitting at the western point of Nemacolin’s Trail, which went on to become the National Road. Brownsville’s role in river travel and commerce includes the production and launch of the nation’s first steamboat, the Enterprise, in 1814. In terms of its industrial legacy, the coal and coke mined in Fayette County passed through Brownsville on its way to feed the steel mills in Pittsburgh. These stories are told through artifacts, maps, photos, models, and paintings. On the second floor is a gallery dedicated to local artist Frank L. Melega. He got his start creating signs for Brownsville businesses.

- When Rices Landing Riverfront was incorporated as a borough in 1903, its streets were lined with shops, taverns, and trading posts. Its abundant natural resources—clay, sand, coal and lumber—helped local businesses prosper. Its proximity to the Monongahela River made it an ideal industrial and transportation hub. More than 100 years later, the stores, coal mines, and lock and dam that once defines this community are gone, but a strong connection to the river and the land remains. One piece of that history remains on a bank above the Monongahela River: Rivers of Steel’s W.A. Young & Son’s Foundry and Machine Shop. Built in 1900, the shop produced parts for steamboats, coal mines, railroads, and local businesses. In 1908, the shop expanded to include the foundry, and twenty years later electricity was added. Very little has changed since the doors closed in 1965—calendars, invoices, tools, patterns are still in place. But the place comes to life when the series of line shaft driven tools are powered up and local blacksmiths fire up the foundry.

- Step back to the dawn of the Electric Age when in 1918 the Pittsburgh Railways Company operated some 2,000 trolley cars, 65 different lines, and 600 miles of track. At the Pennsylvania Trolley Museum in Washington, the nostalgia and history of those days are alive and well. Visitors can step aboard and see the restoration in progress of more nearly 50 cars, interact with hands-on STEM exhibits, and even take a roundtrip ride on a vintage trolley.

Before this region was known for steel, it was known for glass—and by 1920, 80% of the glass made in the U.S. was produced in the Pittsburgh area. Access to the rivers, abundant raw materials and coal supplies for fuel allowed the region to find huge success in the market west of the Appalachian Mountains. One renowned glassmaking company was Duncan and Miller Glass, whose roots can be traced to 1865 producing clear, colored, and patterned decorative glassware. Collectors of the company’s products can be found across the globe, and a large display of gorgeous sugar bowls, creamers, salt and pepper shakers, ash trays, shot glasses, plates, and vases are on display at the Duncan and Miller Glass Museum, which recently re-opened in a larger and updated space in Washington.

Before this region was known for steel, it was known for glass—and by 1920, 80% of the glass made in the U.S. was produced in the Pittsburgh area. Access to the rivers, abundant raw materials and coal supplies for fuel allowed the region to find huge success in the market west of the Appalachian Mountains. One renowned glassmaking company was Duncan and Miller Glass, whose roots can be traced to 1865 producing clear, colored, and patterned decorative glassware. Collectors of the company’s products can be found across the globe, and a large display of gorgeous sugar bowls, creamers, salt and pepper shakers, ash trays, shot glasses, plates, and vases are on display at the Duncan and Miller Glass Museum, which recently re-opened in a larger and updated space in Washington.

Guide to Images

- Detail Richard Hass Steel Town Mural on Byham Theater, Downtown Pittsburgh

- Joe Magarac statue as it appeared at Kennywood, Pre-2009, West Mifflin, PA

- Old Economy Village, Ambridge, PA

- Saxonburg Museum and Roebling Workshop, Saxonburg, PA

- John Roebling diagram for the Brooklyn Bridge

- Debut of the Little Giant Mosaic at the Ruins Project, Perryopolis, PA, June 2019

- Pennsylvania Trolley Museum, Washington, PA

Routes to Roots!

Routes to Roots! Flex your muscles in front of the 15-foot-tall

Flex your muscles in front of the 15-foot-tall  Old Economy Village

Old Economy Village The rural setting of

The rural setting of  Before this region was known for steel, it was known for glass—and by 1920, 80% of the glass made in the U.S. was produced in the Pittsburgh area. Access to the rivers, abundant raw materials and coal supplies for fuel allowed the region to find huge success in the market west of the Appalachian Mountains. One renowned glassmaking company was Duncan and Miller Glass, whose roots can be traced to 1865 producing clear, colored, and patterned decorative glassware. Collectors of the company’s products can be found across the globe, and a large display of gorgeous sugar bowls, creamers, salt and pepper shakers, ash trays, shot glasses, plates, and vases are on display at the

Before this region was known for steel, it was known for glass—and by 1920, 80% of the glass made in the U.S. was produced in the Pittsburgh area. Access to the rivers, abundant raw materials and coal supplies for fuel allowed the region to find huge success in the market west of the Appalachian Mountains. One renowned glassmaking company was Duncan and Miller Glass, whose roots can be traced to 1865 producing clear, colored, and patterned decorative glassware. Collectors of the company’s products can be found across the globe, and a large display of gorgeous sugar bowls, creamers, salt and pepper shakers, ash trays, shot glasses, plates, and vases are on display at the