Kathleen Ferri painting, image courtesy of the artist, by Bob Donaldson for the Post-Gazette.

Heritage Highlights

Rivers of Steel’s Heritage Arts program strives to represent the region’s diverse cultural heritage, from ethnic customs and occupational traditions directly linked to Pittsburgh’s industrial past, to new American folk arts and cultural practices emerging from the region’s diverse urban experience. Usually passed down from person to person within close-knit communities, these cultural traditions are as varied as they are unique, each representing one aspect of what makes southwestern Pennsylvania’s heritage so rich.

In this month’s installment, Rivers of Steel’s Heritage Arts Coordinator Jon Engel shares an in-depth dive into the life and art of local painter Kathleen Ferri. Ferri is a lifelong resident of the Mon Valley, born in Turtle Creek and now living in North Versailles. Her unique works provide deep insight into the Valley of the 20th century, from factory labor to family life.

Kathleen Ferri, Artist & Historian

By Jonathan Engel

Like most Europeans, the Orgills first came to the Monongahela Valley for the mills. They had been living in some English colony—the name of which is one of the few things that Kathleen cannot remember—where the state gave out land through lottery. The Orgills drew the worst, and so their patriarch made for America, specifically for an aunt already living in Lawrenceville. He quickly found employment in steel but burned his hands badly on the job. Now unable to work, he set sail back to his family. Meanwhile, his wife and children had suffered in the colony during a typhoid outbreak and boarded a ship to find him in America. As Kathleen tells it, with a laugh, their ships passed each other in the sea.

“Through people helping them,” she concludes, “they got back together.”

A painting of Braddock in the 1940s by Kathleen Ferri.

Kathleen Ferri (née Orgill) is full of stories like this. “Before TV, families discussed ‘local history’ at the dinner table.” Mainly, these stories are about two topics: family and work. She is a historian of these things in the Mon Valley, a history she records in her vibrant paintings.

Kathleen was born in Turtle Creek in 1926 to two Westinghouse employees, who had met at the company’s East Pittsburgh office. In this story, Kathleen’s father is a dogged romantic hero turned down numerous times by her mother, a young secretary that found employment when most men were drafted into World War I. Shortly before their long-requested first date, Mr. Orgill, a strapping young football player, injured himself on the field. He arrived at the future Mrs. Orgill’s doorstep on crutches and covered in mud, not at all the image of the young gentleman she knew at work. Kathleen laughs again, noting that her mother did not like that very much.

Throughout Kathleen’s life, she also worked at Westinghouse, and at the local bank. Her son Vince worked at U.S. Steel’s Homestead mill. Others of her children and grandchildren have worked and lived throughout the Mon Valley. Thus, these family stories tell about more than just her own life, but about the social conditions of the entire region. When the Depression came, the Orgills—like most of Turtle Creek—were poor. Mr. Orgill worked only two and a half days at Westinghouse and sold sweepers on the side to make ends meet. Still, they made frequent trips to the Penn Avenue business district in downtown Turtle Creek. “During the ‘Depression Days’,” says Kathleen, “money was so scarce, we seldom could afford any new items, but we enjoyed ‘window shopping’ and dreaming of ‘better days’ coming.” These small-town streets and storefront displays were the beginning of a lifelong fascination with local scenes, which was tied intimately to an interest in the metal and manufacturing industries that supported that lifestyle.

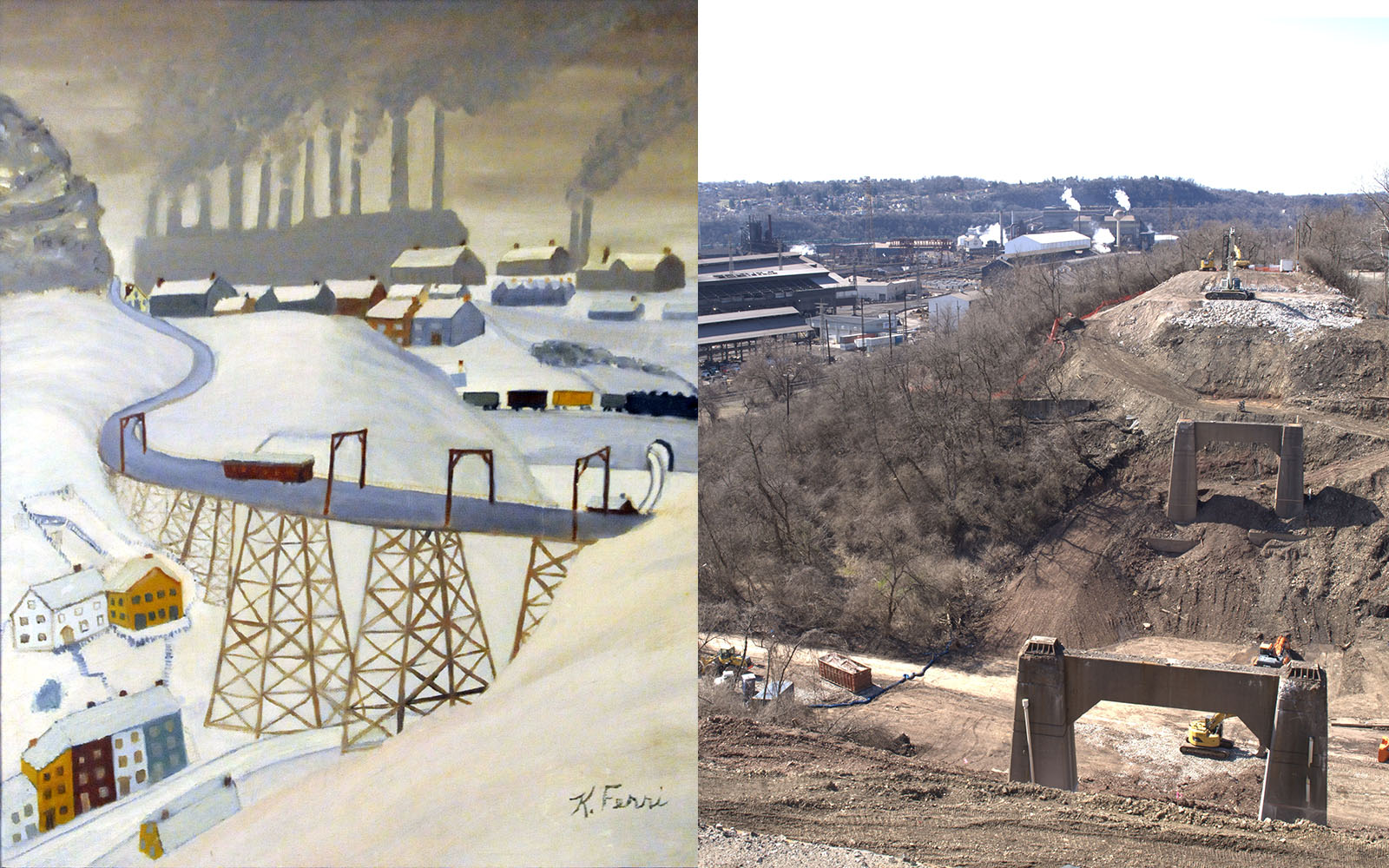

An undated Kathleen Ferri painting of the Homestead Works steel mill and adjacent trolley.

Picking Up the Brush

Kathleen did not begin painting until she was in her sixties. Whenever she tells this story, it is only ever one sentence away from a story about her late husband, Jim Ferri.

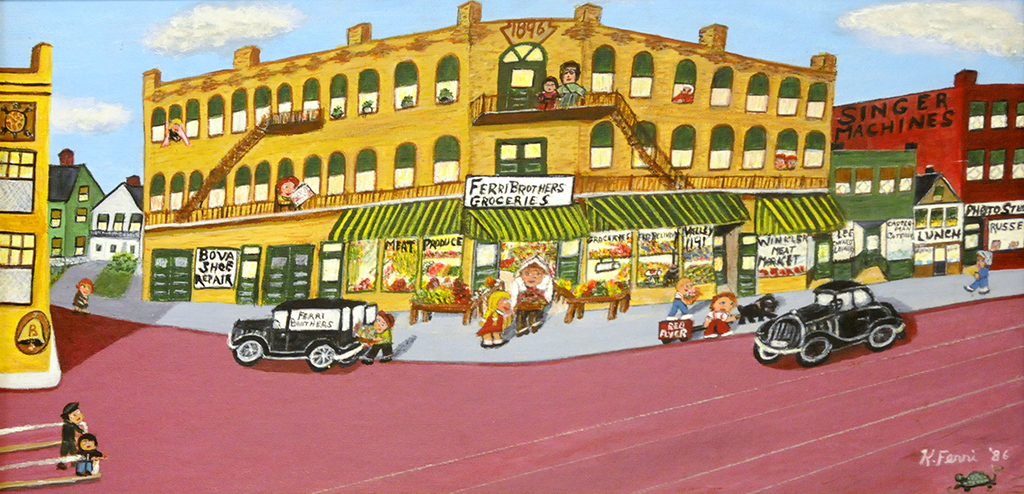

Growing up, Kathleen’s family often visited the local Italian grocery, Ferri Brothers’, which was founded in 1919. Ferri Brothers’ was a key community-gathering place. The first phone in town was installed there. “People would call in from Altoona,” Kathleen says, “‘Can you tell so-and-so her sister died?’” (Mickens, PGH City Paper, 2002). They frequently catered community picnics. The company truck was lent out to anyone who needed help moving.

When she was young, Kathleen met Jim, the owner’s son. One day at the store in 1942, Jim told her he was going to the join the army and asked Kathleen to write him. Reminiscing now, she remembers being skeptical and fiery—“Get out! The army won’t have you!”—but she also remembers crying on her walk home.

They did write. “His first letter was signed ‘Love, Jim!’—and I thought, my mother’s gonna’ kill me, I’m still in high school!” When he returned, the two were married. They raised four kids together and Jim worked in the store that his uncles ran.

A 1986 painting by Kathleen Ferri, showing the Ferri Brothers’ grocery store in Turtle Creek, c. the 1940s.

He passed away in 1984. By then, their children had all moved out to find jobs elsewhere. Kathleen was left lonely and bored. At the encouragement of some friends, she made a social visit to a local senior center. There, she was convinced to stay for a holiday crafts class, making ornaments for the center’s Christmas tree. Told to do “anything”, she made her first painting: a five-inch disk with an image of Mickey Mouse, which she thought little of. After class, she was pulled aside by the volunteer instructor, Shirley Knezevich, who told her: “You are a natural-born artist, I can tell!”

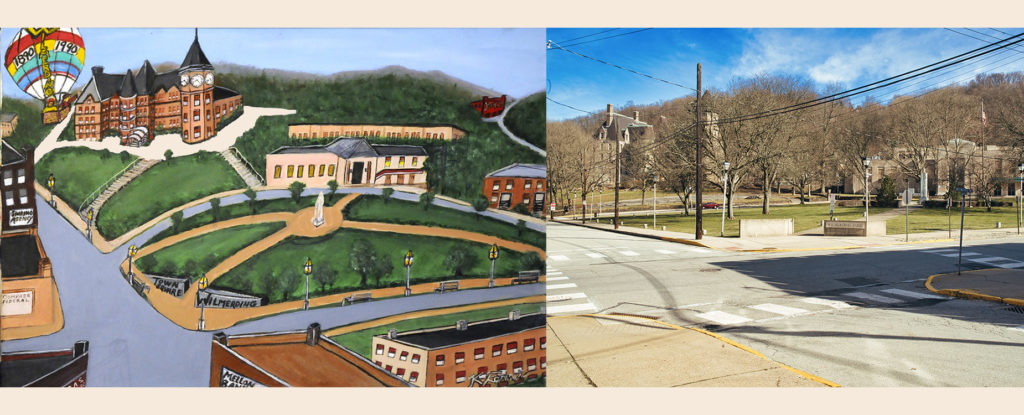

Kathleen and Shirley forged a strong bond. Kathleen began attending Shirley’s classes to paint, staying after to tweak her works with the input of her friend. From the beginning, Kathleen’s paintings were almost always family scenes or scenes of the community. “I thought, well, paint what you know. So I started to paint the little town of Turtle Creek! I love that town! I know everybody and they know me!” Soon enough, she painted Wilmerding too. After that, East Pittsburgh. Then Trafford. Then McKeesport. Then Braddock, and so on. Kathleen has made over 70 deeply detailed paintings over the past 35 years.

Nearly all of these are rendered from a bird’s eye view, even at impossible angles. Still, they remain faithful to the towns’ layouts. Kathleen knows her subjects so well she can picture them from any vantage point. This is because, with few exceptions, she does not paint from photographs or from any other reference. She paints from her memories, especially her memories of being a child in the ‘30s and ‘40s.

Going Over the Faces

A painting of the Strip District depicting the 1940s era by Kathleen Ferri.

Kathleen’s works immediately caught people’s eyes. Not only do they carry a unique visual character, but they capture rarely seen views of the Mon Valley: views of not just industry, but also neighborly living. In 1987, Kathleen entered a painting of Turtle Creek into the Wilkins Township Art Festival and received best of show; in 1988, she showed two paintings at the Three Rivers Arts Festival; and by 1994, her painting of Ferri’s Groceries had won the statewide Senior Arts Festival’s first prize. In 1995, she was part of a large folk artists’ show at the Pittsburgh Center of the Arts, where then-director Murray Horne commented: “I walk through the gallery during the day and hear people commenting that they can do this or that. And it’s true, maybe they can do it too if they pick up a brush” (Norman, Post-Gazette).

Not long after, Kathleen sold the only painting she ever has. (She has, at several points, recreated paintings or sold prints of them, but she has not parted with any of the rest of her originals.) This was a painting of Pittsburgh’s Strip District, to the Heinz Foundation. It is characteristic of her works: a bright red cathedral is in the center, with boats, trains, cars, and little people all about. Many factories surround the church, spitting up fire. In the background, the original Heinz plant sits across the river, the element that intrigued the Foundation. As Kathleen tells it, she sold for a simple reason: the Heinz representatives were kind and described the Berlin Wall to her, so she could paint it.

A 1993 painting by Kathleen Ferri of Burke Glen, a former amusement park in Monroeville. The park operated from 1926 to 1974, just off the Old William Penn Highway.

Kathleen has never received any formal art training. She does not much consider painterly techniques like perspective, lighting, or anatomy. She prefers her own intuition. Her works have been called “childlike” or “primitive” but, really, they are personal. They thrum with the unique rhythm of her “good ol’ days” window shopping: place names, street plans, brick walls, and windows. Often, she calls her paintings “memory scenes”, and designs them as a resident might describe them in a story.

She recalled to me how she painted the Berlin Wall scene from details passed on by the Heinz people and the TV news: “There was tears of happiness, so I have to have tears of happiness in there. And they said there was people dancing in the streets, so I had to put dancing in. And you need to have music, you can’t have them dancing around the lunchbox, so I painted a German man playing music,” and so forth. “I’m not in a rush. As long as something’s recognizable, it’s good—and I can always just go over it a second time!” She can stay up all night, making little improvements just as she did in Knezevich’s class, redrawing clouds and faces.

In Kathleen’s paintings, people are mostly happy. They are happy under blue skies, at play in busy amusement parks like Kennywood or Monroeville’s Burke Glen. They are happy under red skies, at work in smoggy mills like Homestead and Edgar Thomson Works. They are happy in town, at business, and with family. The intimate connection between all these aspects of life is obvious, as is the deep familiarity everyone in town has with each other. Her people—often drawn simply, almost like dolls or toys—are in harmonious community with one other and with their surroundings. Kathleen’s artworks are not just key records of the Mon Valley’s underappreciated boroughs, but of Kathleen’s views of 20th century life. In contrast to the Depression, “steel mills, electric production, and boats on our rivers, and many trucks were the evidence of employment returned once more.”

While she gleefully blends small details like period boats and contemporary cars, she is careful to accurately pin down the precise geography and architecture of the town she is painting. She is not only preserving the visual appearance of these places but a loving view of how the people interacted in them. This has only become more crucial as time has gone on and economic forces have changed these towns.

Left: an undated painting of Dooker’s Hollow Bridge c. the 1940s by Kathleen Ferri. Right: a March 2021 picture of the Dooker’s Hollow Bridge construction siteby Mike Engel. Dooker’s Hollow Bridge spanned a gorge between North Braddock to East Pittsburgh until its detonation in February 2021. Construction on a new bridge is scheduled for later this month.

Hanging the Canvases

Like everywhere in the Rust Belt, Turtle Creek’s industrial economy crashed in the second half of the 20th century. While factories like Edgar Thomson and the Westinghouse Airbrake Factory still remain, they employ far less. As jobs changed, so did the forces and infrastructures that dominate people’s lives. Mill life shifted towards office life and company towns like Wilmerding shifted towards long commutes and large highways. The logic of existence was changing.

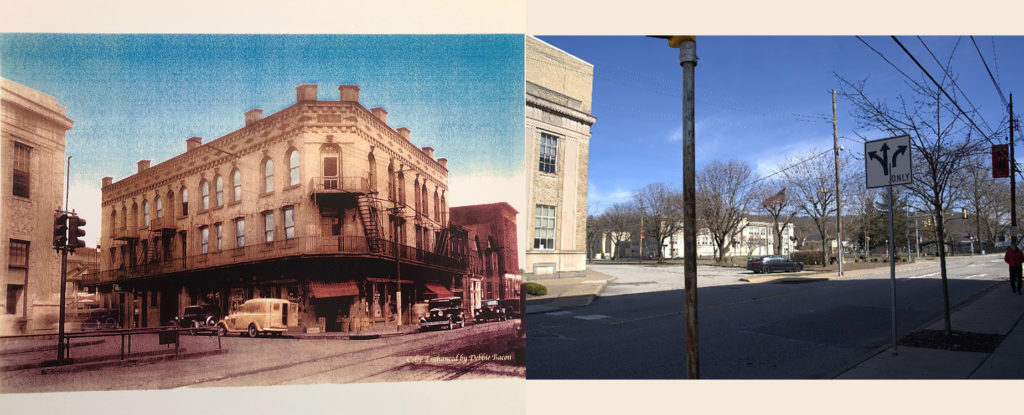

The Tri-Boro Expressway was built through Turtle Creek in the 1970s to connect it to Pitcairn. “You crawl after Pitcairn,” remarks Kathleen. During its construction, Ferri Groceries, along with most of the business district, was demolished. A new, smaller plaza was built in their place. A small Vietnam War memorial was erected where the store once was.

Ferri Brothers’ had been seized through eminent domain. Jim, having lost his job, worked various odd jobs. Kathleen got work at the bank. Though the Ferris survived, the way their neighbors related to each other was forever altered. According to the Census Bureau, the 10,600 people of Turtle Creek in 1960 had become 8,300 by 1970 and 6,000 by 2000. The population now hovers somewhere over 5,000.

“They took the whole town!” Kathleen says, naming the Isaly’s deli and local pharmacy as shops long gone. “[The redevelopment] was successful, but they tore down all the old reliables where you knew everyone”.

Left: a picture of the Ferri Brother’s Groceries building at 901 Penn Avenue in Turtle Creek c. the 1930s. Right: a picture of the lot where the building once stood, taken by Mike Engel in March 2021.

Kathleen’s painting of Ferri’s Groceries is one of the few relics of the store left. It preserves not just the’’ building’s façade, but the way of life the store was integral to, a more communal time when people were more known to each other. Many vanished places still endure in Kathleen’s paintings, and her memory. Perhaps because of this, she is careful to only paint things which she remembers well. Though also lacking formal training as a historian, Kathleen is a diligent one. In addition to her art, until recently, she gave lectures on local history at high schools and volunteered at the now-closed Westinghouse Castle Museum.

Left: a painting of the town of Wilmerding by Kathleen Ferri, made in 1990 for the town’s centennial celebration. Right: a picture of Wilmerding Park by Mike Engel in March 2021. Note the famous Westinghouse Air Brake Office Building on the left of both, nicknamed “the Castle”. The Air Brake company was based from 1889 to 1985, and from 2006 to 2016, operated as a museum to local history. It is now being developed into a boutique hotel.

These days, Kathleen lives in an independent living residence for seniors in North Versailles, not far from Shirley Knezevich. She spends much of her time writing up old family stories, having created a comprehensive Ferri family history with a photo album and paintings to accompany. She has no plans to sell any more of her artworks, which densely line the walls of her apartment. “They’re like my babies. You don’t produce a baby and then sell it.”

They still bring her great joy: “When I hear people try to describe my art, I say, ‘I don’t even know what you’re talking about!’ It just tickled my heart!”

A picture of Kathleen Ferri, c. 2021, with several of her paintings behind her.

A picture of Kathleen Ferri, c. 2021, with several of her paintings behind her.

For this article, my father and I set out to photograph some of the places Kathleen painted as they look now. This proved difficult, as our pictures were somehow never as sharp or as real as her works. Not having lived in these towns as she did, we were earthbound, in earthier tones. Still, I am surprised to say: the colors are really there. In the sunset, industrial grays and tans become alchemical golds and reds. Another generation grows up among these buildings, in Turtle Creek and Rankin and Wilmerding and more, witnessing their own hues, making their own memory scenes.

Kathleen Ferri will turn 95 this July. She has four children, ten grandchildren, and eleven great-grandchildren.

Citations

Kirkland, Kevin. “Artist Kathleen Ferri is a Pittsburgh original”. Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, 21 March 2012.

Mickens, Julie. Interview with Kathleen Ferri. PGH City Paper, November 2002.

Norman, Tony. “School of Life: City’s self-taught artists get own show at PCA”. Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, 1995.

All images of artwork, along with the featured image of the Kathleen Ferri painting, appear courtesy of the artist. They were photographed by Bob Donaldson for the Post-Gazette on Tuesday, January 24, 2012, for the article cited above by Kevin Kirkland.

Read more in the Heritage Highlights series. Check out this interview with Turkish Calligrapher Benjamin Aysan or this interview with drag queen Akasha Van Cartier.