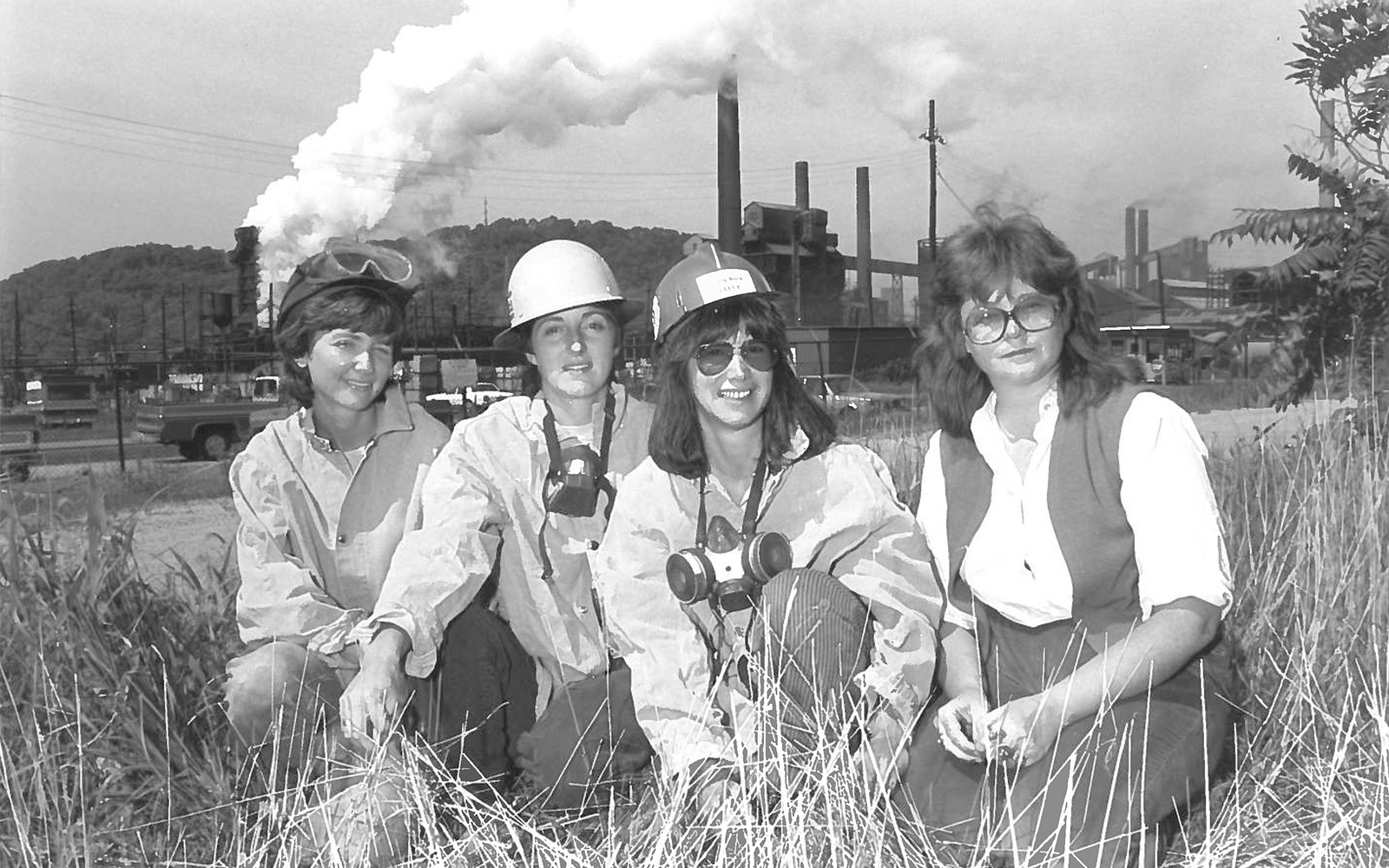

Women of Steel, the production team from the 1985 documentary of the same name— (left to right) Beth Destler, Steffi Domike, Linny Stovall, & Allyn Stewart

Women of Steel—Steffi Domike

By Brianna Horan

By Brianna Horan

When Steffi Domike graduated from college in 1975 with a degree in economics, so many of the jobs available to women at the time didn’t pay well. Not wanting to go to graduate school, she decided to move to Pittsburgh to work in the steel industry, which had recently been in the headlines for affirmative action policies meant to correct past discriminatory policies against hiring minorities and women.

“It was the beginning of the women’s movement, and there was this consent decree. It was national news that women could work in the mill, and I found that intriguing,” Domike says. “The idea of getting into the mills was a foreign experience, but not that bad. I thought I could try it, and it paid better than what my friends were getting with their college experience so I went for it.”

The mill environment at United States Steel’s Clairton Coke Works certainly embodied a place like no other she’d experienced. “I found it to be an interesting world to inhabit. The mill was a different kind of world. In fact, you’d walk in, clock in, go to the locker room, and then you would put on your disguise—your clothing—because it was head to toe,” she says. “I worked in the coke works so it was yellows—we had to wear yellow suits made of very tightly woven cotton as a protective layer against the coke oven fumes. And then there’s metatarsal arches on your feet, and then there’s a respirator, and then there’s a hard hat, sand safety glasses, gloves. There wasn’t a lot of flesh exposed. And then the scenery was a whole other world—it was like living on the moon. The jobs we did were like nothing else I’d ever seen. The machinery was unique to the industry, and the whole thing was a different world.”

Steffi Domike via Zoom screengrab.

Domike was born in the United States but grew up in South America because of her father’s work for the United Nations—so being back in the U.S. after so long also felt somewhat foreign at the time. Her job at U.S. Steel as a janitor and then electrician apprentice, along with her involvement with the United Steel Workers of America Local 1557 while she worked there, would end up rooting her career in activism and organized labor.

The 1974 Basic Steel Consent Decree that was a catalyst for Domike’s consideration of the steel industry was a settlement between nine of the nation’s steel companies that represented more than 75% of the steel industry. It was the result of suits filed mostly by Black steelworkers in the Alabama and Chicago area, and also at Homestead. With the legal backing of the 1964 Civil Rights Act, it required companies to end longtime discriminatory hiring and promotion practices against minorities and women. They also had to pay more than $30 million in retribution, shift to a company-wide seniority system, and abide by a mandate to award half of all bids into trades & crafts apprenticeships to people who were Black, had a Spanish surname, or were women. The other 50 percent of these bids would go to white men based on overall seniority – not department seniority.

“Before the consent decree, folks who were hired were hired into specific departments and couldn’t get out, and the company would hire people into departments really based on their ethnicity,” Domike says. She describes the clear patterns she observed where skin color, last names, and family connections determined how grueling and demanding a person’s job in the mill would be, with little chance of moving to another department. “Whatever the skill of your ethnicity, or whatever the track was for your race… they would just track you. The consent decree sort of stopped that… What happened was the favored groups no longer had that pull. When I talk to people who are critical of affirmative action, I say, ‘Well, it really leveled the playing field for all white people as well.’”

For the first nine months of her employment at the Clairton Works, Domike was the first female janitor, hired to clean the numerous new women’s locker rooms and bathrooms that had been created across the massive plant. Her gender solved a problem that had developed when men were cleaning these facilities; they were an ideal place to lock the doors and take a nap on the job. “So when the guys’ bosses were looking for them they couldn’t find them, and the women couldn’t use the facility. So that became a small crisis within a crisis – and that’s why they hired me! I could clean the locker rooms and women could still use them,” Domike says. “I got an education, because even though I had a college degree I hadn’t done a lot of cleaning, and, you know, I needed to learn.”

Once she’d worked there long enough to be eligible for apprenticeship training in other areas of the mill, she started to bid on the different opportunities that were posted but was repeatedly passed over. After an electrical job to train and join the wire gang that Domike applied for was given to a white worker with seven years of experience, one of the grievance officers noticed the discrepancy between the hiring practice and the policies laid out by the consent decree. “He came up to me and introduced himself and said, ‘Hey, you put in for this bid and they hired the white guy, but the way the consent decree reads, they’re supposed to give 50 percent of the bids to Blacks and women and people with Spanish surnames. But it looks to me like U.S. Steel is trying to get around that by just putting one bid up at a time.’ So I signed a grievance, because he was trying to defend the consent decree, and I was fortunate enough to kind of go in on the coattails of that.” The grievance was settled by opening up the wireman apprenticeship job to both the first man who was hired and to Domike; training took place at the Duquesne Works, where the apprenticeship school was. “It was a really good job, because now I know something that people think is useful to know—how to put in receptacles and run wire.”

Domike also learned how to stand up for herself and other women who were simply trying to do their job in a male-dominated environment. Some of the women she befriended on the job were training and working as diesel mechanics, millwrights, and welders. “For the most part, the men didn’t really want us there. We’d been forced upon them [by the consent decree]… There were some people who wanted to make it really uncomfortable.” She said there were reports of assaults, a lot of harassment, and some women were even asked to sign papers stating that they weren’t capable of doing the work. Domike remembers a woman, the daughter of one of the plant’s managers, who returned to the locker room day after day in tears following her shift. “I finally got it out of her that the guys in the cable crew were so resentful of her presence that they tied her up during the day. They tied her hands together with the zip ties that they use now for handcuffs, and they tied her to a work box, a big metal box, and left her there all day.” Domike confronted the leader of the cable crew that day, and although she herself “got some wild eyes after that,” her co-worker was never tied up again. “What I learned—and I learned this from the other women, but also from some of the supportive guys, is how to stand up to a bully. And nobody likes a bully; they don’t even like themselves.”

Domike was active in a group of rank and file women in the U.S. Steel plants who formed an unofficial group that they called Women of Steel. They started putting out a newsletter of the same name in March of 1979, written by and for USWA women in districts 15, 19, and 20—Domike was a frequent contributor. A similar kind of publication had been established at the Edgar Thomson Works called Hear, Here. An article in the first issue of Women of Steel answered the question, “Why get together?” It stated that the group’s meetings were open to all steel workers, and their aim was to solve common problems together with their brothers, while pointing out that there are “special forms of harassment … reserved just for us.” Seventy steelworkers came to the first Women of Steel meeting to talk about issues that women face in the mills, like “arbitrary firings during probation, overcrowded and inconvenient locker and washrooms, harassment and denial of [Sickness and Accident] benefits during pregnancy, discrimination in job training and apprenticeships, and sexual harassment.” It called for local union women’s committees to further the “good stands” that had already been made, and to increase the equality and unity within the union.

Being an active member of her local union was another part of the appeal for Domike in joining the steel industry after college, where she had written her undergraduate thesis on cooperative business models. “The Steelworkers Union was and still is one of the largest and most powerful industrial unions in the U.S. and North America,” she says. “I wanted to learn about it, and the best way to learn about it is to get right in.” She represented her local in the USWA Civil Rights Committee, and ran for recording secretary in 1979, as well as contributing to the Steel Workers Stand Up newsletter. Women’s issues and obstacles to employment were not unfamiliar territory for her, either. At the same time that Domike was graduating from high school, her mother was graduating from law school. Despite her qualifications, she struggled to get a job in a law firm and instead found employment in the Internal Revenue Service with the aid of affirmative action programs at work in the government. “My mother was a pioneer in her own way. She fought all her life to be taken seriously.”

After five and a quarter years at U.S. Steel, the industry-wide shutdowns and lay-offs hit Domike’s job in 1981. By then, she had completed her wireman schooling but was just shy of completing the training hours needed to make top rate. “I got laid off along with everyone else, and everyone else was looking for a job. So what room there was for craftspeople in the market was pretty well taken up. It was really hard to find a job in the early ’80s,” she says.

Many Women of Steel members initiated unemployment campaigns, and created foodbanks in Homestead and McKeesport where “thousands of people” came for food. Domike was working for the Mon Valley Unemployed Committee while also studying filmmaking at the Art Institute and Pittsburgh Filmmakers. Along with three other women that she worked with at the MVUC, Domike created an oral history project called Crashin’ Out: Hard Times in McKeesport, which compared the decline of the steel industry in the 1980s with the Great Depression in the 1930s. “It was great sadness in our communities when, starting in ’77, the jobs dried up and the mills closed, because whole communities were just dependent on that constant job,” Domike says. “People, particularly men, hadn’t really planned for what they could do besides work in the steel industry… They felt sort of shunned. There were generations of families that had fathers, grandfathers, great-grandfathers, and uncles all working in the mills.”

Before long, Domike was producing documentaries like 1985’s Women of Steel, which chronicled the struggles that laid-off female steelworkers faced in the wake of the steel industry’s collapse, and The River Ran Red, which portrays the 1892 Homestead lockout and strike from the workers’ perspective. Her artwork and activism have brought attention to feminist, environmentalist, and labor themes. She is currently a labor educator at United Steelworkers. You can watch Women of Steel, The River Ran Red, and Out of This Furnace: A Walking Tour of Thomas Bell’s Novel, all produced by Domike, on YouTube by clicking this link. The playlist also features a recording of a recent USW program, “The Origin Stories of Women of Steel.”

Today, the United Steelworkers (USW) has an activist-arm called Women of Steel that evolved from the early women’s caucuses that demanded a seat at the table in the union. The USW Constitution requires that each local union with female members must establish a Local Union Women’s Committee. USW considers all of its female members to be Women of Steel regardless of their union-position or the industry or service that they work in.

Take a look at the University of Pittsburgh Library System’s highlights from its Steffi Domike archives, where you can page through a pamphlet that Domike wrote called Snappy Answers to Stupid Questions: Some Hints for Women in the Mills for Getting Through the Verbal Abuse, along with the first issue of the Women of Steel newsletter, and other pieces of her collections. Here’s a zinger: Question: “What does your husband think of you working here?” Response: “1. What does your wife think?” or “2. He likes the paycheck as much as I do.”

This article was published to coincide with Women’s History Month. For another article on women in steel, read Shining a Light on the Ciloets.