The Historic Preservation of the Carrie Blast Furnaces

This past fall, when the tour season ended at Carrie, construction season began. Working along with Century Steel Erectors, Rivers of Steel has initiated the first of several significant projects that will facilitate the stabilization of the Carrie Blast Furnaces and allow for expanded access to previously restricted parts of the site for visitors.

These latest projects are part of the historic preservation work on this National Historic Landmark that began when Rivers of Steel first started to manage the site in 2010. In these first dozen years, the reach and impact of Rivers of Steel’s work at the site has been exponential. Tens of thousands of visitors experience the Carrie Blast Furnaces each year. Now, as the Regional Industrial Development Corporation (RIDC)-led development of the adjacent Carrie Furnace site has begun, including the building of two tech-flex structures, we anticipate this trajectory to continue. With more exposure and visitation projected, the historic preservation and stabilization of the Carrie Blast Furnaces National Historic Landmark is crucial now more than ever.

A view of the Ore Yard in 2011; one year after Rivers of Steel began its stewardship of the site, a path has been cleared for tour groups.

Dispelling the Myths

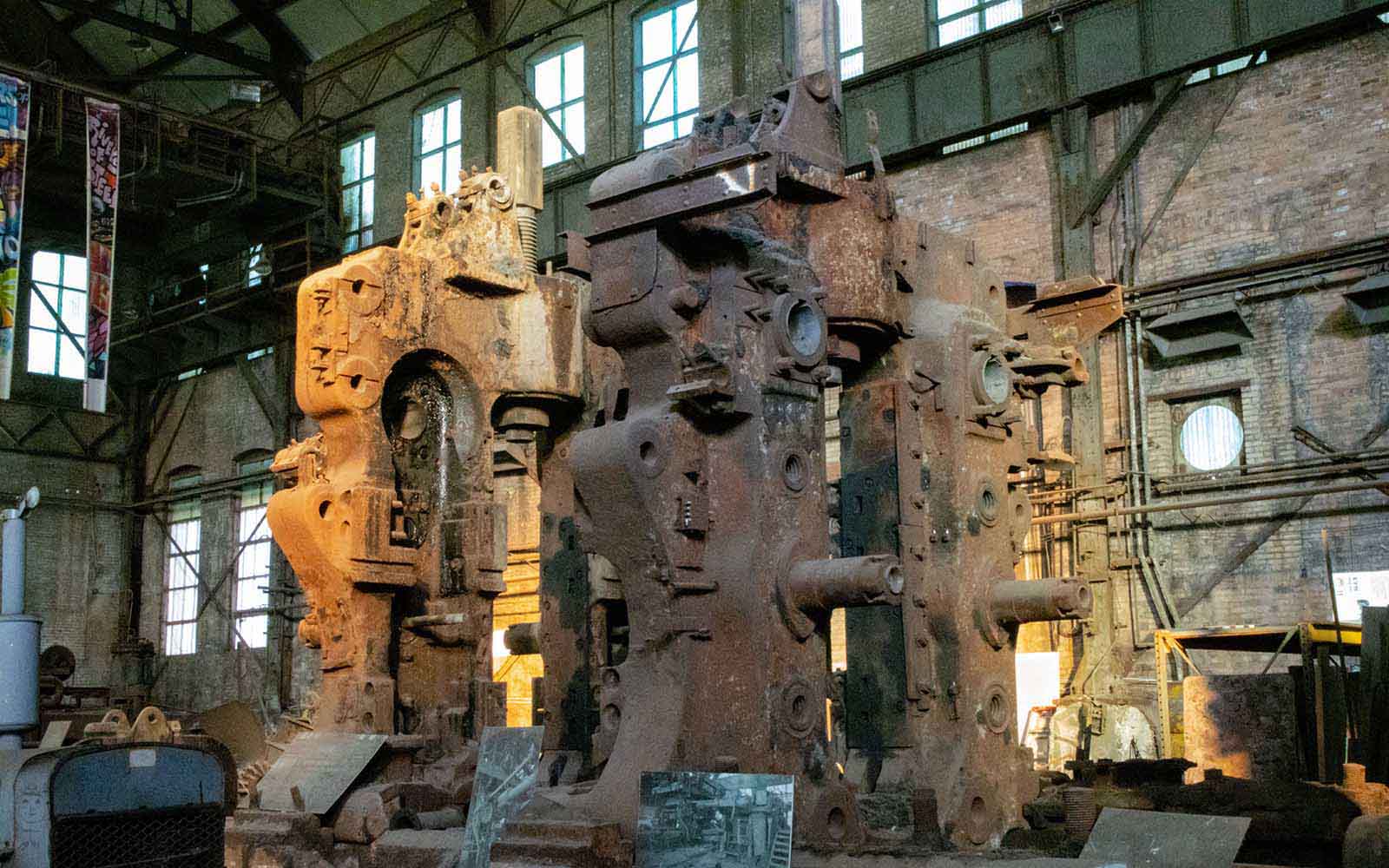

Beyond being an industrial and cultural icon in our own region, the Carrie Blast Furnaces are a standout in international industrial heritage preservation. Following benchmarking trips as part of a comprehensive master planning project Rivers of Steel undertook over the last year, we discovered that the Carrie Furnaces have one of the best-preserved cast houses in the world. Additionally, Rivers of Steel’s arts programs—including metal arts and graffiti arts—are lauded by our global counterparts as an innovative way to introduce audiences to our site and the importance of industrial heritage preservation. Most people who stumble on Carrie—through channels outside of our word-of-mouth or marketing presences—are introduced to it as an “abandoned” place; it became internet famous (with the help of cable television shows) for its rust and overgrowth, as well as for the Carrie Deer guerilla art sculpture.

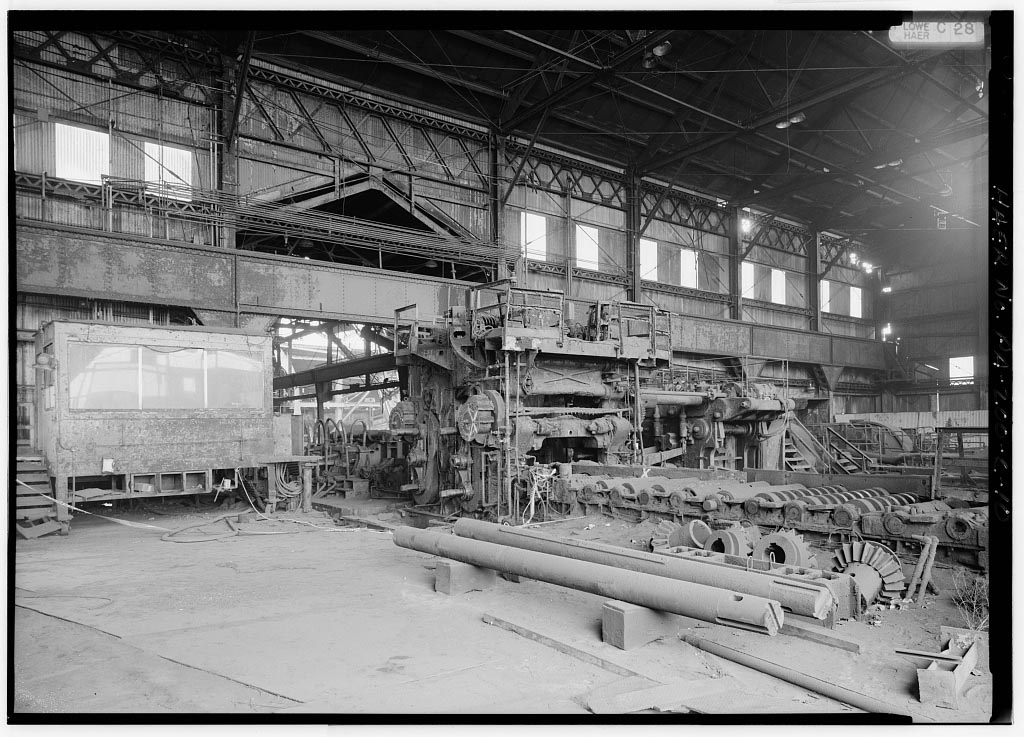

To be fair, the site sat empty and unsupervised for quite some time. Furnaces #6 and #7 (which remain today) went offline in 1978. The rest of the plant closed in 1984. It sat, as is, until 1988, when the Park Corporation took ownership and focused on scrapping most of the buildings—including two of the remaining four furnaces—while Rivers of Steel fought to save what it could from demolition. Then, the Redevelopment Authority of Allegheny County took over ownership in 2005. The following year, Rivers of Steel secured National Historic Landmark status for the Carrie Blast Furnaces #6 and #7 and became stewards of the site in 2010. Thus, there were over twenty-five years when Carrie was not in daily use. However, locals know that it was never truly “abandoned.” It was frequented by artists, graffiti-writers, and everyday folks—people who were looking to connect with part of our region’s heritage by entering a place that was off limits to the public during its heyday.

From the last years of the plant’s operation until Rivers of Steel took stewardship of the historic site in 2010, the structures of the National Historic Landmark did not undergo any care or maintenance. This essentially means that Rivers of Steel has been playing historic preservation and stabilization “catch-up” for those decades of neglect.

A view of the Central Courtyard as it appeared in 2006. Image by Randy Harris.

What It Means To Be a National Historic Landmark

National Historic Landmarks represent an outstanding aspect of American history and culture; they are places that illustrate the nationally significant history of the United States.

The Carrie Blast Furnaces contribute to the understanding of how the Pittsburgh region was responsible for creating the steel that transformed the world’s infrastructure during the 20th century, a time when it also earned the title of “arsenal of democracy” for its military supply contributions for our national defense. On a more human scale, this vestige of the past helps Rivers of Steel to share the stories of our region’s workers and their families, their accomplishments and sacrifices—actions that help define the character of our communities even today. Yet when you consider Carrie’s landmark status from a maintenance point of view, it represents both challenges and opportunities that are as unique as the stories it represents.

Sun streams through the roof of the AC Power House in 2008, reflecting the state of neglect prior to Rivers of Steel’s stewardship. Photo by Ron Baraff.

Historic Preservation Work on an Industrial Scale

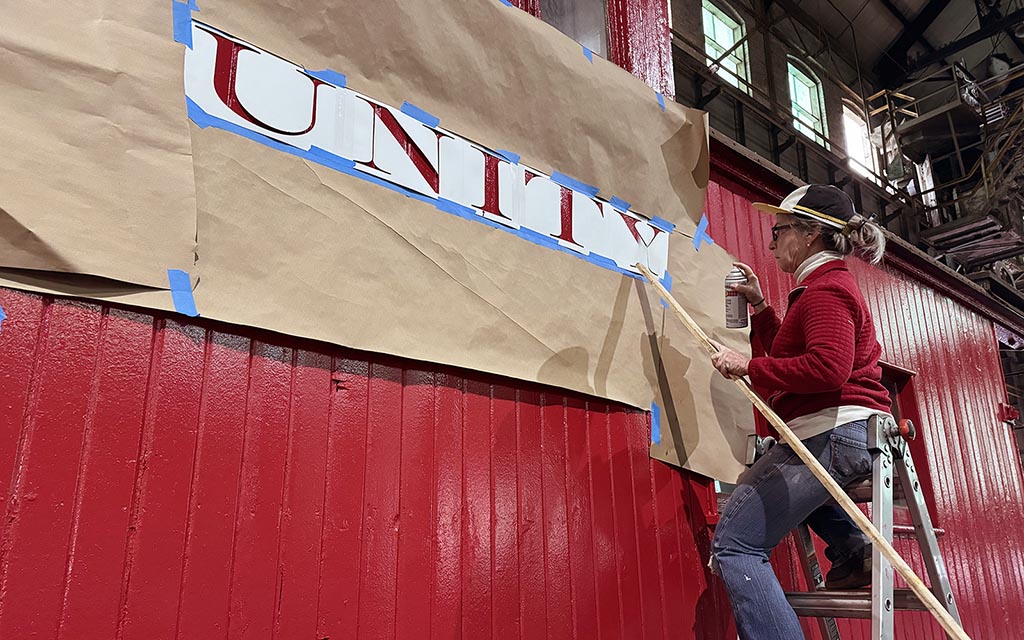

Upon being granted stewardship of the Carrie Furnaces, Rivers of Steel immediately began addressing the preservation of the site, guided by the Secretary of the Interior’s Standards for the Treatment of Historic Properties. Rivers of Steel’s staff and a handful of volunteers worked tirelessly to pull back overgrowth, especially from the structures where it could continue to degrade the architectural integrity. In 2011, staff raised the funds for the first major stabilization project, installing a new roof on the AC Power House, along with other smaller initiatives. This triage work, occurring roughly from 2010 to 2015, helped to slow the rate of degradation and open up spaces to make them safe for visitors . . . but there was more work to be done.

“2010 marked the beginning of our hands-on work at the site to reclaim it as a historic landmark,” said Ron Baraff, Rivers of Steel’s director of historic resources and facilities. “Not only did we have to learn how to creatively manage the landscape and formulate best practices in preservation on the fly, but we also had to change the culture of the site that had developed over the previous twenty-plus years. No longer was it an “abandoned” or dormant site, it was a National Historic Landmark that needed to be protected and nurtured.”

“While we fully understood the attraction that the site had become,” Baraff continued, “it was incumbent upon us to ensure its long-term safety. To do so, we had to tackle not just the encroachment by nature, but also by scrappers, urban explorers, and the curious. To this end, we worked diligently to secure the site and initiate stabilization efforts.”

Safety has always been the first priority. Rivers of Steel performs regular structural surveys to determine a priority listing of issues to be addressed. In 2017, on the second major stabilization project, with funding from the Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission (PHMC) Keystone Preservation grant fund, Rivers of Steel worked with Songer Services to remove 75 feet of distressed steel and brick from the Hot Stove’s Draft Stack and place a cap on it. This project ensured that Rivers of Steel could continue to safely bring visitors onsite.

Over the last five years, much needed work has been done by a few full-time staff members of Rivers of Steel. Life safety, security, electricity, and lighting systems were installed, including in the AC Power House, where most events and programs take place.

The Glory Daze motorcycle show is just one of the events that was hosted in the AC Power House last year. Photo by Adam Piscitelli / Primetime Shots, Inc.

Big Challenges and Big Money

The historic preservation efforts at Carrie exist beyond the scope of many historical landmarks. Most of the time, professionals that are versed in historic restorations specialize in more traditional types of structures, like historic homes or brick or stone buildings. Preservation and restoration experience on industrial structures is quite limited, especially within the United States. Last year, Rivers of Steel’s efforts to determine the best path forward led to researching work that’s been done in Europe, particularly in Germany’s Ruhr and Emscher Valleys, the Saarland, and in parts of Belgium and Luxembourg. Rivers of Steel also joined TICCIH, the International Congress on the Conservation of Industrial Heritage, to connect with colleagues globally to discuss the unique challenges we face.

Over the past two years, with the support of Senator Jay Costa and other state and federal elected officials, Rivers of Steel has raised significant funding for continued preservation and stabilization, including funding from the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania’s Redevelopment Assistance Capital Program; the National Park Service’s Save America’s Treasures grants program; the National Endowment for the Humanities Challenge Grant; and the PHMC’s Keystone Historic Preservation grant program, along with support from local foundations and corporations.

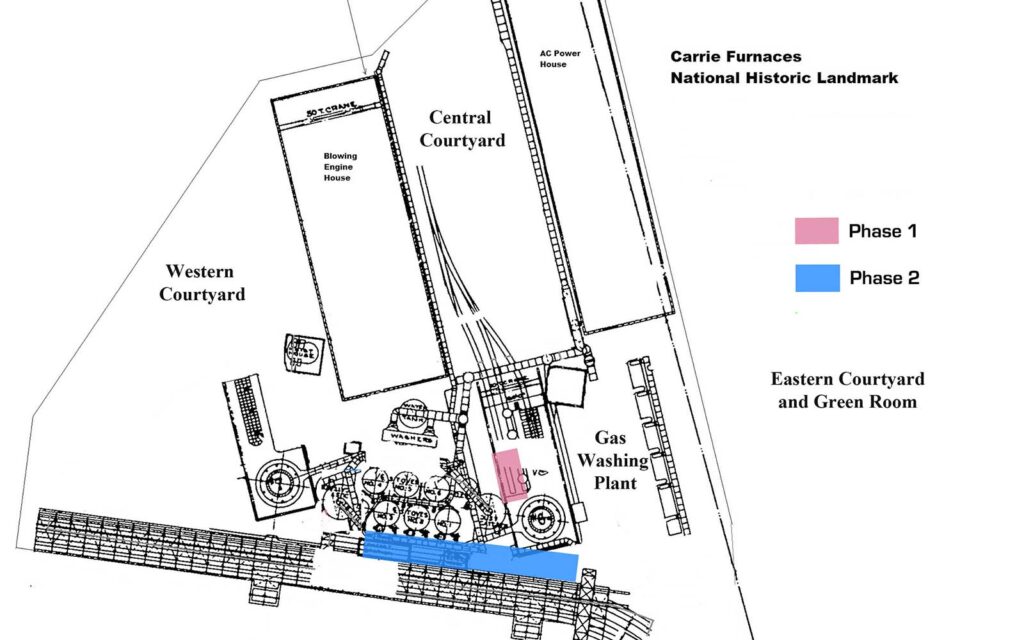

This site maps shows the areas of work for the project currently underway in the offseason at the Carrie Blast Furnaces.

Our current project—the first major undertaking since the stack stabilization—includes stabilizing the #6 Cast House, rebuilding the sluiceway behind the Cast House, opening up the sluiceway alley to visitors for the first time, and additional stabilization work that will continue to allow visitors on the Stove Deck. Funded by the Save America’s Treasures and Keystone Historic Preservation grants mentioned above, this work is crucial to Rivers of Steel’s interpretation of the site, which features industrial tours that follow the iron-making process.

Additional projects are also pending. With the support of U.S. Senator Bob Casey in 2021, Rivers of Steel received a Save America’s Treasures grant for stabilization work on the shell of the AC Power House, including concrete and masonry repair, along with the paving of the internal ramp. Beyond structural integrity, this will improve the usability of this historic building.

Recently Senator Bob Casey and former Congressman Mike Doyle both announced separate federal grants for stabilization work on the Blowing Engine House. These funds will support the work necessary to preserve and stabilize the building following historic guidelines, and lay the groundwork for securing occupancy of the building. This is the first very important step toward the Blowing Engine House becoming the Visitors’ Center for not only the Carrie Blast Furnaces site, but for the entirety of the Rivers of Steel National Heritage Area.

Augie Carlino, president and chief executive officer of Rivers of Steel, lauded the support from the elected officials and said, “Senator Casey, Congressman Doyle, and State Senator Jay Costa are strong advocates for Rivers of Steel and our work at Carrie and throughout the National Heritage Area. In addition, Allegheny County Chief Executive Rich Fitzgerald is delivering on his promise to work with Rivers of Steel, RIDC, and the communities surrounding Carrie to make the site’s development a priority for Allegheny County, positioning the development for 21st-century jobs.”

How the Furnaces looked during the Festival of Combustion in 2022. Photo by Ron Baraff.

A Vision for the Future

As mentioned briefly above, Rivers of Steel has completed a comprehensive master plan for the Carrie Blast Furnaces National Historic Landmark site. Approved just this past December by the Board of Directors, the master plan not only recommends steps to stabilize and preserve the historic structures, but also includes plans to renovate and reuse existing interior spaces—and build new structures—for interpretation, exhibition, education, recreation, and special events. The Carrie Blast Furnaces are the centerpiece of Rivers of Steel’s operations—the hub reaching out to the spokes of our other historic and touristic sites as well as our many heritage partner sites throughout our eight-county National Heritage Area.

The implementation of this master plan is on the horizon. Rivers of Steel’s vision dovetails with what has been planned by RIDC and the Pittsburgh Film Office for the adjacent commercial development, as well as with what Allegheny County plans for the Rankin Hot Metal Bridge, also a National Historic Landmark.

Each step of the way, we have been working with our community partners in Rankin, Swissvale, Braddock, and North Braddock, along with the Redevelopment Authority of Allegheny County, and now, RIDC, on the preservation and redevelopment of the entire development site.

As Rivers of Steel has done with other redevelopment projects in Duquesne and McKeesport, we are working to ensure that former industrial sites are interpreted for the public and their stories are told. Unlike those other redevelopments, including the much-lauded Hazelwood Green, the Carrie Furnaces development is a National Historic Landmark. While this adds more stringent guidelines for redevelopment, the result will be an internationally known destination—an asset for our immediate neighbors in the Monongahela River Valley and to the many visitors the site will draw to the region.

It has been a long time coming for Carrie, for the team here at Rivers of Steel, for our partners, and for the residents of the region who have been working to build its future. We are on the precipice of a new era and we are grateful to be the stewards of this landmark—a space that reflects the resilience of our region’s people, both historically and today.