The Ultimate Holiday Happenings Guide for the Rivers of Steel Heritage Area

The Ultimate Holiday Happenings Guide for the Rivers of Steel Heritage Area

Holiday merriment brings light and warmth as the nights grow longer and the air turns frosty around the winter solstice. ’Tis the season—and however you celebrate it, there’s a lot of fun to be had in the Rivers of Steel National Heritage Area! We’ve assembled the ultimate guide to events and activities happening throughout the region over the next month, which range from classic observances to new twists on tradition!

As you make your plans, be sure to check the organization’s website and social media to stay informed of updates to pandemic safety protocols.

We wish you all a healthy and happy holiday season around the Heritage Area!

Events: December 4, 2021

AWC Community Day: Holiday Edition at the August Wilson African American Cultural Center

This family-focused party at the August Wilson African American Cultural Center is filled with festivities indoors and outside, including performances by the Center’s hip-hop campers, Brandon Terry’s Fusion Illusion Band, Kwanzaa drummers and dancers, a choir, and a DJ. There’s a Kwanzaa educational workshop, a visit from Santa, and a free hot chocolate bar!

Event website and Facebook page.

Chanukah Bash hosted by Jewish Federation of Greater Pittsburgh, Young Adult Division

Join Pittsburgh’s young adult community for an evening of joy and light to celebrate Chanukah at Iron City Circus Arts in Pittsburgh’s South Side. Attendees will enjoy an open bar, hot donuts from Bella Christie, music, aerial dancers, and more. Capacity is limited and advance registration is recommended.

Event website.

Chanukah Celebration: Light Up Night 7 hosted by the Jewish Community Center of Greater Pittsburgh

All are invited to this free, family-friendly program at the JCC in Squirrel Hill. There will be crafts, games, and sufganiyot (Israeli donuts!), followed by Havdalah and a Chanukah candle lighting. Attendees are asked to bring a new, unwrapped toy to be distributed through the Christian Church of Wilkinsburg to children who celebrate Christmas.

Event website.

Christmas at Old Economy Village

Events: December 4 – 5, 2021

Christmas at the Village at Old Economy Village

Walk along a candlelit cobblestone street and visit the historic buildings with interpreters eager to show off wares from the nineteenth century. People looking for last-minute gift ideas will find unique handmade items for sale by vendors. Local choirs will be performing. Children’s crafts and activities along with Belsnickel, a fur-clad companion to St. Nicholas from German folklore, will be found in the Granary. Food is available for purchase.

Event website.

Christmas on the Farm at Freedom Farms

This Valencia farm will have local Christmas trees and wreaths available for purchase, along with food, face painting, and access to the petting zoo and corn pit. Santa will be at the farm, along with dozens of handmade product vendors for special holiday gifts.

Event website.

Christmas Open House at the Greene County Historical Society

Enjoy an old-fashioned Christmas at the museum with visits by Santa, decorations, and more in Waynesburg.

Event website.

Greedy Christmas at Diamond Theatre of Ligonier

This hilarious original production takes us to Miami, where the December temps are high, and people’s greed is causing chaos—even Santa Claus finds himself in legal trouble. Judge Jude E. might be able to save Christmas—or make it worse!

Event website.

2021 Christmas Festival at Shady Elms in Hickory.

Shady Elms Farm Christmas Festival

Kick off your Christmas celebrations with Santa, Mrs. Claus, Buddy the Elf, and many more characters at this farm in Hickory, Washington County. Check out the food trucks, private workshops, and local small business vendors!

Event website.

Vandergrift Back When Holiday Extravaganza

Head to Vandergrift, on the northern edge of Westmoreland County, to enjoy activities for the whole family, including a parade, craft and food vendors, live entertainment, a cookie contest, caroling, Christmas trivia, a gingerbread house contest, and more.

Event website.

Events: December 5, 2021

Bushy Run Children’s Christmas Party

Look forward to games, crafts, entertainment, and a visit from Santa at this site of a pivotal battle fought between the British and Native Americans during the conflict known as Pontiac’s War in 1763 in what is today Jeannette, Westmoreland County. The party is intended for children ages 5 to 12 years.

Event website.

Chanukah Games at Temple David

Temple David in Monroeville welcomes spectators to cheer on teams of all ages as they participate in a variety of fun activities and challenges to earn points and win prizes! The closing ceremony and Chanukkiah lighting will also be streamed on Zoom.

Event website.

Made in the U.S.A. holiday toys.

A Local Santa’s Workshop with Channel Craft Toys at the Westmoreland History Education Center

Since 1983, Dean Helfer, Jr., has kept alive the tradition of wooden toys, games, and puzzles with his “Made in the USA” company, Channel Craft, in Charleroi, PA. Items are tailor-made for thousands of specialty toy and gift stores, museums, parks, and attractions. Join Dean for an informative talk about his business, along with toy demonstrations and giveaways. This presentation is great for adults and children alike.

Event website.

Events: December 6, 2021

Hazelwood’s Light Up Night

The snowflake lights on Second Avenue will be aglow, and businesses all along Hazelwood’s main street will have music, food, and activities for the whole family. Enjoy live music and food trucks, along with lawn games, face painting, balloon arts, horse and buggy rides, live ice carving, a photo booth with fairytale princesses and superheroes, and more! It’s also the perfect time to check out the Illumin-Ave art project, which features a series of five light and art installations along Second Avenue through January 31, 2022.

Event website.

Krampus Fest 2021

Maybe you’re not on the “nice” list this year—Krampus Fest is the place for you. Live music and festivities abound in Market Square in downtown Pittsburgh, where Krampus will also visit to bring coal and pose for socially-distanced photos. True to German Alpine folklore, Krampus is a horned, anthropomorphic figure who deals with the children who have misbehaved while Saint Nicholas brings gifts for those on the “nice” list.

Event Facebook page.

Three Centuries of Christmas

Event: December 11, 2021

Three Centuries of Christmas

Discover how American Christmas traditions changed over three centuries on this special holiday tour of Historic Hanna’s Town. Costumed guides lead you through buildings from the 18th, 19th, and 20th centuries that are adorned in period-correct decorations and share stories of Christmases past. When people came to America, they brought the traditions from their homeland with them. Learn about the origins of the Christmas tree, the tradition of mailing cards, the evolution of Santa Claus, and so much more while enjoying the historical ambiance of Hanna’s Town and sampling holiday treats.

Event website.

Event: December 12, 2021

A Magical Wurlitzer Christmas at Lincoln Hall in Foxburg

Travel just north of Heritage Area to Clarion county to give yourself the gift of A Magical Wurlitzer Christmas with the keyboard artistry of the Dave Wickerham on Sunday, December 12 at 2 p.m. in Foxburg’s Lincoln Hall. One of the preeminent theatre organists acclaimed internationally, Dave Wickerham performs his theatre organ arrangements of Christmas carols, anthems, and joyous holiday songs.

Event website.

Events: December 14, 2021

Fused Glass Poinsettia Workshop at Main Exhibit Gallery & Art Center

Head out to Ligonier, Westmoreland County, to learn how to cut basic glass shapes and layer them to fuse a poinsettia suncatcher. Assemble your own design to be fired in the kiln that evening, and then pick up your beautiful glass art the next day.

Event website.

Remembering the McGinnis Sisters: Food & Family Stories, presented virtually by the Senator John Heinz History Center

Take part in a discussion of food traditions and innovations with one of Pittsburgh’s most renowned food families, the McGinnises. The McGinnis Sisters were recognized as one of the region’s early leaders in the gourmet and specialty food business, and visiting their store was a holiday staple for generations of Pittsburghers to find special ingredients for traditional foods. The conversation will be led by Dr. Ashley Rose Young, Food Historian at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History and daughter of Sharon McGinnis Young. Joining the discussion are McGinnis sisters Bonnie McGinnis Vello and Noreen McGinnis Campbell, as well as Jennifer Daurora, part of the third generation who ran the family business.

Event website and registration.

Event: December 17 – 19, 2021

The Nutcracker Ballet at State Theatre Center for the Arts

The State Theatre in Uniontown, Fayette County is proud to produce the annual production of The Nutcracker Ballet featuring local dancers of all ages performing the classic story to Tchaikovsky’s beautiful score, choreographed by Donna Marovic. Make this beautiful production of The Nutcracker part of your family holiday tradition with this beautiful performance!

Event website.

Events: December 18, 2021

Carnegie Christmas with Goats

Enjoy a day in Carnegie with the family, and get your photo taken with Santa and a goat! Enter your pet in a costume contest, do some holiday shopping, and listen to caroling throughout the day. In the evening, a Wassail Walk features adult beverages and an ugly sweater contest.

Event website.

Holidays Around the World

Holidays Around the World at Community Library of Allegheny Valley

Bring the kids and celebrate holiday traditions from around the globe in Natrona Heights, with Bright Star Theatre. Join Nick and Joy in their quest to make it home for the holidays. Winter traditions and holidays are celebrated in this show. From Kwanzaa to Christmas to The Festival of Lights, this unique production offers people a look into the celebrations that occur around the globe during this special time of year. Suggested for grades K & up. Registration required due to limited space.

Event website.

The Mexican War Streets Winter Wonderland Extravaganza

The Mexican War Streets Society welcomes all to this Victorian neighborhood on Pittsburgh’s North Side for a picturesque evening stroll of lights, decorations, and community cheer to highlight the area’s history.

Event Facebook page.

Event: December 20, 2021

Cookie Swap at the Carnegie of Homestead

Bring your favorite holiday cookies to share with your community and build a unique cookie tray with baked goods from other bakers in the Adult Reading Room at the Carnegie of Homestead.

Event website.

Event: December 26, 2021

Kwanzaa Queen at Painting with a Twist

Get creative at Painting with a Twist in Pittsburgh’s South Side, where you’ll paint a Kwanzaa-inspired design on a canvas or wood plank board to decorate your home.

Event website.

Event: December 28, 2021

Winter Warm-Up Hike with the Wampum Chapter of the North Country Trail Association

You’ll get nice and toasty on a four-mile hike along the North Country Trail. Meet up at the Darlington Trailhead, where you’ll be shuttled to Hodgson Road before hiking back to Darlington, where a hot cocoa bar, pastries, and snacks will be waiting for you.

Facebook event.

Event: December 29, 2021

Holiday Family Day at Westmoreland Historical Society

The Westmoreland Historical Society welcomes all ages to Historic Hanna’s Town for a fun day of activities celebrating winter and the holiday season. There will be winter crafts, cookie decorating, history-themed story time, and musical interludes. Demonstrations of holiday celebrations in the late 18th century take place fireside at Hanna’s Tavern, and walking paths are open for self-guided tours of holiday history. The Westmoreland History Shop will also have holiday items on sale at 40% off.

Event website.

Events: December 31, 2021

Highmark First Night Pittsburgh

Ring in the new year at this free, family-focused evening of outdoor performances, hands-on fun, and fireworks to start 2022 on a celebratory note. The night begins with fireworks at 6 p.m. for kids with early bedtimes, and ends with the grand finale fireworks at midnight.

Event details.

New Year’s Eve, 2019 at Historic Harmony

Silvester New Year’s Eve in Harmony

Harmony is a town with deep German roots, and the Harmony Museum invites one and all to celebrate Silvester and the arrival of the new year at 6:00 p.m. on December 31—when it’s midnight in Germany! The Silvester celebration, so named by Germans because New Year’s Eve is also the feast day of Pope Sylvester I, kicks off with a 5K run / walk & 1-mile fun run. Afterwards, gather at the Harmony Museum lot for a Christmas Tree Toss as well as a kid’s wreath toss, and enjoy the warmth exuding from the Gluhwein (mulled wine) Hut. A take-out pork & sauerkraut dinner can be ordered ahead, and there will be music in the town square. Stick around for the ball will drop and fireworks will glow at 6 p.m.!

Event information.

Ongoing Events

Allegheny County’s Holiday Music Program

The sounds of the season will fill the Grand Staircase of the Allegheny County Courthouse (436 Grant St., Pittsburgh, PA 15222), where high school orchestras, jazz ensembles, choruses, choirs, and bands will perform throughout December. Audiences are invited to participate in the Holiday Project to provide holiday gifts to children in families receiving Department of Human Services support.

Performance Schedule and Details.

The Black Market: Holiday Edition

This pop-up market supports and showcases Black-owned businesses from around the region and is a buzzing destination in Downtown Pittsburgh during the holiday season, located at 623 Smithfield St. December 4, 5, 11, and 12, 2021.

Event website and vendor list.

A Creepy Christmas at The ScareHouse

Pittsburgh’s scariest haunted house is filled with creepy toys and evil elves to torment naughty boys and girls as The ScareHouse opens for the season December 10, 11, 17, and 18, 2021. Parental discretion is advised for children under 13.

Event website.

Christmas by Candlelight at West Overton

Christmas by Candlelight at West Overton Museums

This year, Christmas will look a little different at West Overton! Take a candlelit tour of the 1830s Overholt home on Saturdays and Sundays in December. Enjoy historically accurate decor as you learn the development of some of our most beloved Christmas traditions and how the Overholts celebrated (or not!) in the 1800s. As you tour room to room, follow their traditions over the century and learn about Christmas in southwestern PA as far back as 1800, the lore of gift givers like Belsnickel and Santa Claus, and the origins of other customs. There will be tasty treats and warming drinks, along with the opportunity to sample and purchase a bottle of the first whiskey made at West Overton since Prohibition. Advance tickets are recommended due to limited capacity.

Event website.

Christmas with Santa & Alpacas at WestPark Alpacas

Have your picture taken with Santa and his alpaca helpers in Slippery Rock! You may roam the pastures with the alpacas while feeding them treats! The shop will be open for your alpaca Christmas shopping. Open December 11, 18, 19, 22, and 23, 2021.

Event website.

Gingerbread House Contest in Ligonier Town Hall

Visit Ligonier Town Hall at 120 E Main St., Ligonier, PA 15658, to create your own gingerbread house, or vote for your favorite from December 3 – 12, 2021.

Event website.

Holiday Lights at Kennywood Park

Stroll among more than one million twinkling lights, and marvel at the tallest Christmas tree in the state of Pennsylvania, surrounded by the nostalgia of Kennywood Park. There are rides for the kids and special entertainment for all, along with festive new foods and holiday drinks. Ongoing, select nights through January 2.

Event website.

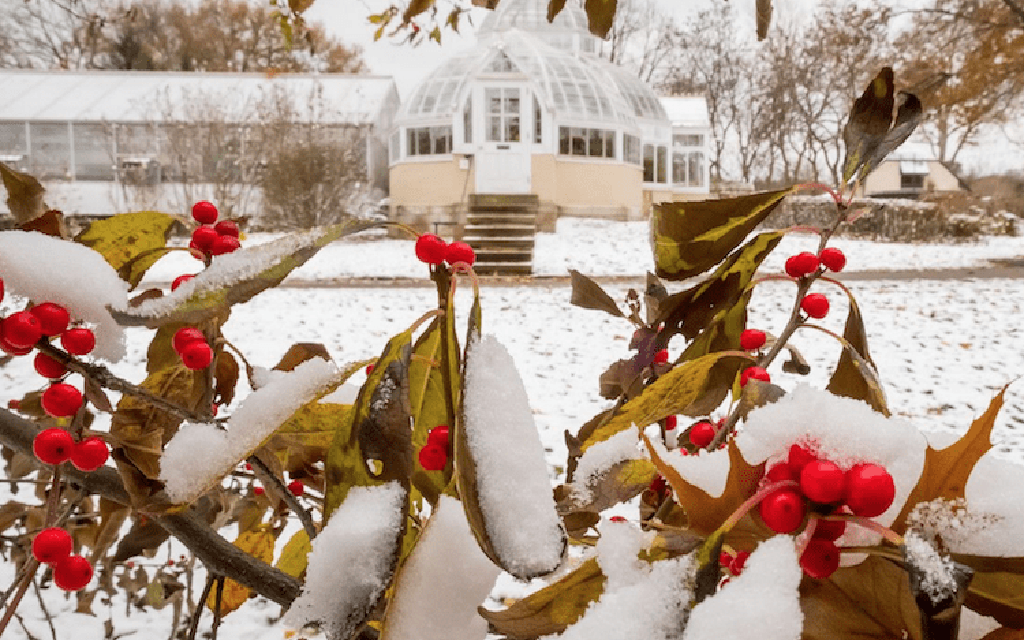

Winter Flower Show and Light Garden at Phipps Conservatory and Botanical Gardens

The gardens are aglow at Phipps Conservatory for the winter flower show, Sparkle and Shine! Enjoy holiday trees, topiaries, detailed scenes, and more than 1,600 poinsettias. This year marks the return of the Winter Light Garden, with luminous orbs, trees, fountains, a tunnel of lights, and an all-new ice castle display.

Event website.

Holiday KidsPlay Selfie Garden in the Heinz Hall Courtyard

Take fun family selfies with cutouts and character standees from your favorite Fred Rogers Productions children’s TV series, open daily through December 28, with story times on select Sundays.

Event website.

Model Train Exhibits

Model railroaders are passionate about their craft all year round, but many welcome the public to enjoy the scenes in miniature that they recreate with loving detail.

NextPittsburgh highlights five of them here.

Penguins on Parade at the Pittsburgh Zoo and PPG Aquarium

Cold-loving penguins are always dressed for winter weather, and on weekends through February 27 they’ll take a walk to explore the world outside of the PPG Aquarium—as long as the weather is below 45 degrees and nonhazardous.

Event information.

Pittsburgh’s Skyline at Christmas by JP Diroll

People’s Gas Holiday Market

Shop from more vendors than ever before as you stroll through an illuminated Market Square at the tenth annual Peoples Gas Holiday Market, weaving through wooden chalets brimming with high-quality gifts and holiday experiences uniquely filled with international flair and local charm. This is the 10th Anniversary of the Market, which is open daily through December 23.

Event website and vendor list.

Pittsburgh Creche Display in Downtown Pittsburgh

The Pittsburgh Creche is the only authorized replica of the Nativity scene that Saint John Paul II commissioned for the Vatican, and 2021 marks the 23rd year that it’s been on display in Pittsburgh. The 30-ton structure is assembled at U.S. Steel Plaza by labor union volunteers, serving to train apprentice carpenters. Display information, featuring a 3-D model.

Pittsburgh Cultural District’s Holiday Performances

Downtown Pittsburgh’s Cultural District is filled with cheer and festive performances across its many theaters and venues. Get in the spirit and enjoy the arts—check the performance schedule here.

Santa Trolley at the Pennsylvania Trolley Museum

Santa Trolley at the Pennsylvania Trolley Museum

The Pennsylvania Trolley Museum’s stockings are hung by the trolleys with care with the knowledge that Santa Claus will soon be there! The man in red will join visitors for a ride aboard a beautifully restored antique streetcar in Washington, and visitors can also marvel at a large Lionel toy train layout and LEGO display by Steel City Lug. Children can make a craft, and all are welcome to enjoy complimentary hot chocolate and cookies.

Event website.

The Strand Theater’s Holiday Events

This restored classic theater on Zelienople’s main street has a festive line-up of live performances and movies this season.

Event Listing.

The UPMC Rink at PPG Place

This outdoor ice skating rink is back for its 20th year, surrounded by the sparkling spires of PPG Place. Tuesdays are family nights, with one child admitted free with each adult admission.

Event website.

Vanka Murals Holiday Lights Tours

The Millvale Murals of Maxo Vanka are a sight to be seen any time of year, but during the holiday season St. Nicholas Croatian Catholic Church is dressed in its Christmas best for an especially festive experience. You’re invited to celebrate the season with the Vanka Murals and a docent-led tour with all the trimmings on the following dates: December 26, 27, 28, 29, and 30, and January 2, 3, 4, 5, and 6. The 60-minute tours begin at 7:00 p.m. with light refreshments served in advance. Cellist and docent David Bennett will perform before select tour dates.

A Very Merry Pittsburgh exhibit at the Senator John Heinz History Center

This special exhibition is sure to make you feel like a kid again, featuring family keepsakes and imagery that explores how western Pennsylvanians have celebrated major winter holidays, including Christmas, Hanukkah, Diwali, and Kwanzaa. There are also decorations and artifacts from department stores of Downtown Pittsburgh’s past, like Kaufmann’s, Macy’s, Horne’s, and Gimbels. Kids age 17 and younger get free admission to the History Center in December, and Santa visits on select Saturdays for socially distanced photos. Exhibition website.

Winterfest and Winter Lights at The Frick Pittsburgh, courtesy of The Frick Pittsburgh,

Winter Lights at The Frick Pittsburgh’s Winter Garden

Looking for an outdoor space to gather with friends and loved ones during the dark and chilly days of winter? The Frick Pittsburgh has extended their hours and decorated their beautiful grounds with live greenery—as was the Frick Family and Gilded Age custom. Twinkling lights are strung up in the grounds’ winter garden to make for magical surroundings. It all culminates in Winterfest, from December 28 to January 2, when the grounds will be alive with storytelling, carolers, wagon rides, ice skating, and more.

Information about Winter Lights. Information about Winterfest.

World’s Largest Pickle Ornament

It’s a big dill that only in Pittsburgh can you find the World’s Largest Pickle Ornament! All decked out for the holidays, the giant, three-story high Heinz pickle balloon is a sight to relish at EQT Plaza in Downtown Pittsburgh, located at 624 Liberty Ave.

Event website.

Celebrating Silvester in the Historic Harmony District

Celebrating Silvester in the Historic Harmony District

Celebrating Silvester in the Historic Harmony District

Celebrating Silvester in the Historic Harmony District

Community Spotlight

Community Spotlight