A Christmas Miracle inside the Beltway

During the final days of the 117th Congress, the National Heritage Area Act of 2022 was passed by both the House and Senate. It awaits a final signature by President Biden. While any legislation is a triumph in a sometimes politically contentious era, this particular story is nothing shy of a Christmas miracle.

For more than two decades, Rivers of Steel, along with other National Heritage Areas, has been working to secure a National Heritage Areas program bill in an effort to ensure stability, not just for our organization but also for National Heritage Areas (NHAs) across the United States. Finally, decades of work came to fruition in a matter of hours . . . but it very nearly did not happen.

Darkness Descends on the Winter Solstice

The situation was bleak. It was the morning of Wednesday, December 21, and coincidentally the darkest day of the year. There were three days left in the 117th Congress, and the National Heritage Area Act appeared to be dead on arrival. The usual channels for passage of any Heritage Area act—as part of a public lands bill or an omnibus spending package—had failed in the days prior.

In fact, it would not be an exaggeration to think that the future of National Heritage Areas was on the line. Forty-five of the fifty-five National Heritage Areas, including the Rivers of Steel NHA, were on course to lose their Congressional authorization in the coming months. And without legislative authorization, a National Heritage Area cannot receive federal funding. For Rivers of Steel, this equals a substantial portion of our annual operating budget as a nonprofit.

Many of the National Heritage Areas had spent the past ten years attempting to receive reauthorization—only to find themselves receiving temporary, short-term extensions. For Rivers of Steel, this drama played out in 2012, 2015, 2020, and again in 2021. Without action from Congress, the Rivers of Steel National Heritage Area would sunset on September 30—just nine months from now.

Despite the odds, all was not lost . . .

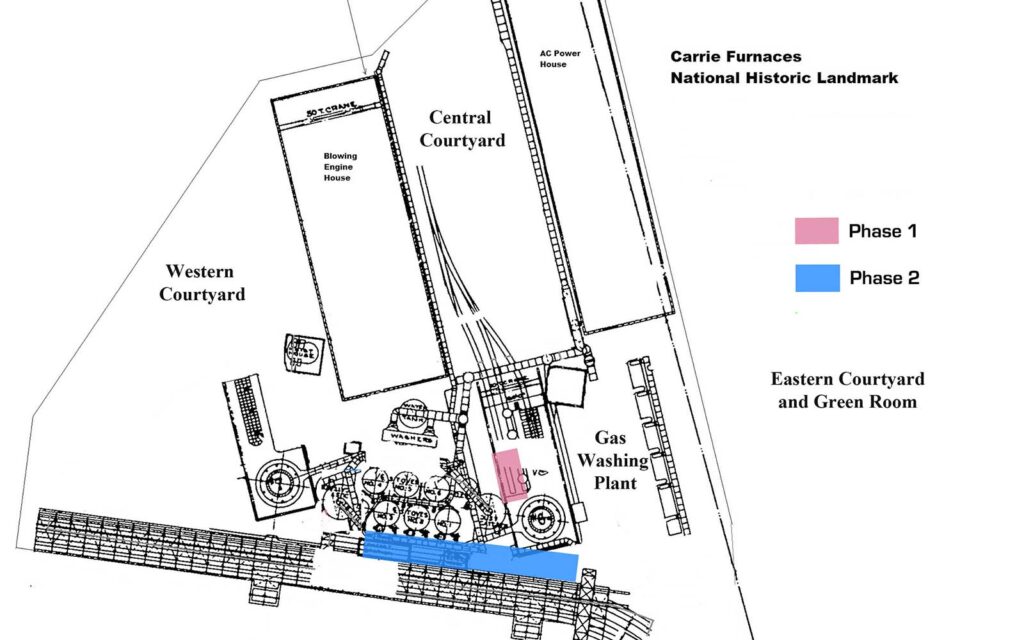

The Carrie Blast Furnaces, a National Historic Landmark with the Rivers of Steel National Heritage Area.

Rivers of Steel’s Role as a National Heritage Area

Before we go further, it is important to share what it means to be a National Heritage Area.

National Heritage Areas are designated by Congress as places where natural, cultural, and historic resources combine to form a cohesive, nationally significant landscape. Through their resources, Heritage Areas tell nationally important stories that celebrate our nation’s diverse heritage. For Rivers of Steel, Congress recognized southwestern Pennsylvania’s industrial and cultural heritage as being nationally significant to the story of America.

Through a public-private partnership with the National Park Service and the Pennsylvania Department of Conservation and Natural Resources, Rivers of Steel supports heritage conservation, heritage tourism, and outdoor recreation as a means to foster economic redevelopment and enhance cultural engagement.

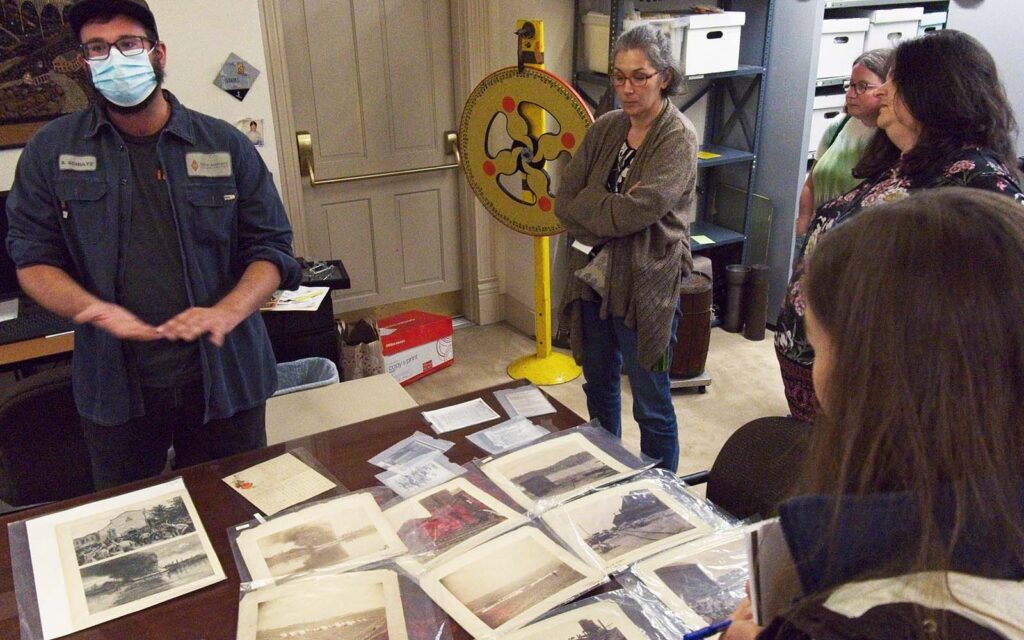

What this work looks like in practice can vary from year to year, but it serves as a guiding principle for our work. Heritage tourism, be it at the Carrie Blast Furnaces, on the Explorer riverboat, or through the eight counties that compose the Rivers of Steel NHA, is among our most visible practices to the public. However, programs like our Mini-Grant Funding, made possible through our role as a National Heritage Area, strengthen the network within the region by aiding other organizations working to achieve goals like ours. Through creative placemaking programs, we collaborate with communities to raise the standard of living through the arts. Even outdoor recreation becomes part of our scope of work!

Now with that understanding, we can continue our story . . .

Designations without an Overarching Federal Program

The first National Heritage Area was designated in 1984. After that, Rivers of Steel was among a handful to be created in a small wave of authorizations in 1996. Subsequent additions occurred in 2000, 2006, 2009, and more recently in 2019, which brought the total to fifty-five National Heritage Areas in thirty-four states.

Despite the proliferation of NHAs, Congress has designated each one with its own individual legislation to work in partnership with National Park Service (NPS). However, unlike the NPS system of national parks, seashores, and battlefields, among others—where there is a congressionally designated program that governs how those units are defined and how NPS and the unit work together—there has never been a comprehensive program established for NHAs.

The lack of a national program for NHAs has proved problematic at many levels. Examples of challenges include:

What planning is necessary to petition to become an NHA? In what ways should the National Park Service work with NHAs? What rules must an NHA follow for their spending of appropriations? Finally and most importantly (and what has contributed to the current disordered state of National Heritage Areas), how should National Heritage Areas be funded?

A National Heritage Area legislation would create a program within the Department of the Interior and could secure a stable foundation for federal funding. In the process, it would streamline the regulatory bureaucracy for NHAs while creating a sound foundation for each National Heritage Area to plan for the future, focus on their missions, and be less distracted by the constant need for reauthorization.

L to R: Tim Fenchel, Deputy Director, Schuylkill River Greenways National Heritage Area; Augie Carlino, President and CEO, Rivers of Steel Heritage Corporation; Joseph J. Corcoran, Executive Director, Lackawanna Heritage Valley National Heritage Area; U.S Senator Bob Casey; Elissa M. Garofalo, former Executive Director, Delaware & Lehigh National Heritage Corridor; Elaine Paul Schaefer, Executive Director, Schuylkill River Greenways National Heritage Area.

Attempts at a Program Bill

Since 2001, there have been attempts to pass a program bill to house National Heritage Areas. Funnily enough, the first of these was drafted by opponents of NHAs and intentionally designed to kill off each NHA. When Rivers of Steel’s President and CEO Augie Carlino chaired the Alliance of National Heritage Areas in the late 1990s through the mid-2000s, he and the coalitions of NHAs worked Capitol Hill to defeat those early bills.

After that, he and the Alliance worked with supporting members of the House and Senate to write a program bill that created a partnership with the National Park Service—one that fostered a sensible process for the designation of new NHAs and a policy that governed existing NHAs.

With every Congress since 2002, the Alliance of National Heritage Areas has advocated for this program bill’s passage. Unfortunately, those efforts failed in every congressional session since 2002.

Bipartisan Efforts and the 117th Congress

With that short history lesson covered, that brings us to the current Congress—the 117th. Here’s where our story gets a bit wonky for a minute, but it also sets the stage for this miraculous saga:

The National Heritage Area Program Bill was reintroduced, along with several other bills, for every NHA needing to be reauthorized. Senator Bob Casey and Congressman Mike Doyle took the lead on the reauthorization of Rivers of Steel.

The U.S. House of Representatives and Senate held hearings and mark-ups (votes to approve the legislation) on the program bill, with the individual reauthorization bills now added as one legislative package. Also included in that bill was legislation designating six new NHAs and authorizing the study of several others for possible future designation.

Despite the vigorous efforts that played out over the two-year cycle of the 117th Congress (2021 and 2022), an attempt to include the NHA package into a much larger public lands bill was attempted, but Congress could not reach an agreement.

After the bill failed to reach a compromise, the only remaining legislative vehicle was the end-of-year omnibus appropriations bill, which Congress needed to pass in order to continue federal government funding and operations. The NHA coalition tried to get the NHA program bill package attached. For a short time, things looked promising, but that also failed on Thursday, December 15, when the effort to get congressional leadership approval was unsuccessful.

Congressional staffers declared the whole NHA package dead, and it looked like everything would need to start over again with the new Congress when it convened in January 2023.

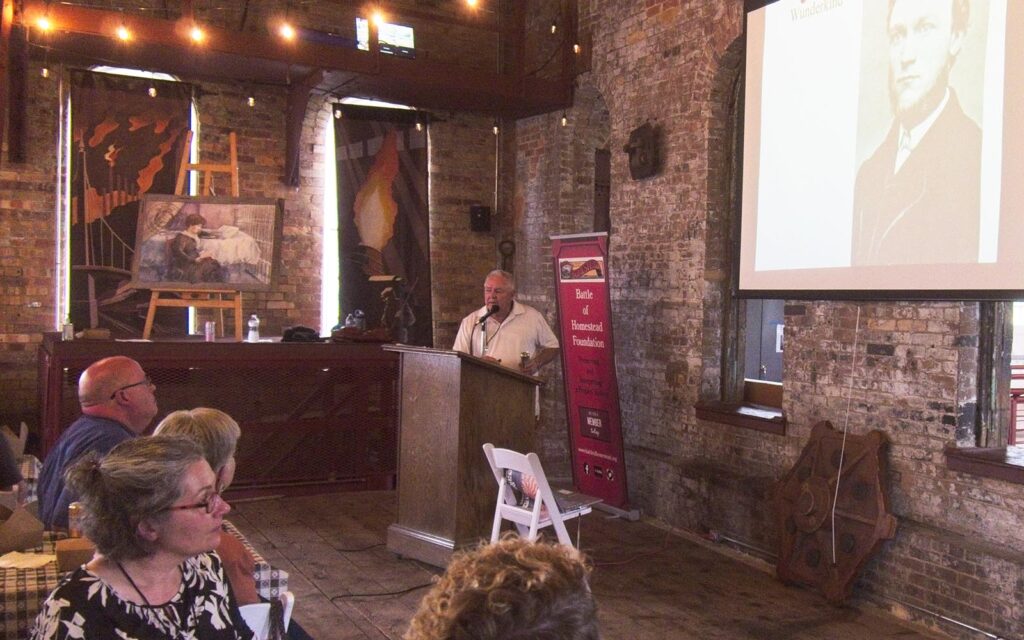

Sara Capen, Executive Director of the Niagara Falls National Heritage area and Chair of the Alliance of National Heritage areas, testifing before the House Appropriations Committee’s Subcommittee on Interior, Environment and Related Agencies.

Sara Capen’s Long Shot

Despite the gloom, there was still one (complicated) path forward. With Congress still in session working on the federal government funding package, there was possibly time to resurrect the NHA legislation.

First, the House and Senate leadership and committee leaders would need to agree to advance the package. Next, objections by senators, if any, were required to be cleared. And after that, another House committee—the Rules Committee—would need to meet to establish the guidelines of debate and voting procedure on the House floor before the bill could be considered.

Under any other situation, that process would typically take weeks or even months. The NHAs had a few legislative days remaining. Even if the bill had the votes, it was unlikely to move through this procedural hurdle in time. But a Christmas miracle did occur.

Enter Sara Capen, the executive director of Niagara Falls NHA and chair of the Alliance of National Heritage Areas. She and a small group of NHA executives began strategizing on possibly saving the NHA legislation and advancing it for a vote.

They worked with Senate leadership to resolve and remove outstanding objections to the legislation, allowing the Senate to consider the legislation. The bill passed on Tuesday evening, December 20.

Next, the legislation was sent to the House of Representatives. But President Zelensky of Ukraine arrived in Washington, DC, and Congress paused for an entire day on Wednesday for his speech, consuming another precious legislative day. With that unplanned event taking a day off of the legislative calendar, many said “good try” to the NHAs as only two days remained for Congress (Thursday and Friday)—and those were already reserved for the other bills.

A Window in Time Opens the Door for a Christmas Miracle

As stunning as it was to get the bill as far as it had, what ensued in the next 24 hours was truly remarkable. Because the Senate still had to vote on the omnibus appropriations bill to fund the government, there was a window of time for the House to consider the NHA package.

In the House, rarely (if ever) do non-critical bills get through in one half day. That only happens with nationally important bills like economic relief packages, end-of-year government funding, or other nationally significant legislation. However, with determination by Congressman Paul Tonko (D-NY), the leading sponsor of the bill, and an onslaught of bipartisan House members, the NHA legislation was debated on the House floor.

The NHA bill passed the House on Thursday afternoon (December 22) by a vote of 326-95, with all Democrats (217) and 109 Republicans voting in favor. A true, bipartisan victory!

The National Heritage Area Act (H.R. 1316/S. 1942) provides our nation’s fifty-five National Heritage Areas with certainty and predictability by extending their authorization for fifteen years, establishes a streamlined process for the foundation, designation, and management of new National Heritage Areas, designates six new Heritage Areas, and authorizes several more National Heritage Area studies.

What once was an experiment in a new way for the federal government to work with communities to conserve the nation’s nationally significant history and culture was now a permanent program fortified by the thirty-year track record of successful NHAs across the United States.

As part of what was passed, Rivers of Steel received a fifteen-year extension of its authorization and is eligible for additional federal funding.

The bill has been sent to the White House and is awaiting a signature from President Biden to be signed into law.

Strong Support from the Pennsylvania Congressional Delegation

Rivers of Steel is overjoyed, and we thank our representatives in Congress for their support! All of the House members representing our area—Congressman Mike Doyle, Congressman Mike Kelly, Congressman Conor Lamb, and Congressman Guy Reschenthaler—voted in favor of the NHA package, as did our two senators, Bob Casey and Pat Toomey.

“I’m pleased to have supported the reauthorization of the Rivers of Steel National Heritage Area,” said Congressman Mike Doyle. “This legislation is a strong endorsement by the United States Congress of the organization, and it guarantees Rivers of Steel’s continued work in southwestern Pennsylvania for the next 15 years, preserving the industrial legacy of our region while our communities transform into a new economy.”

And Rivers of Steel would be greatly remiss if we did not extend our thanks and appreciation to Sara Capen and the Alliance of National Heritage Areas. Augie Carlino, Rivers of Steel’s president and CEO, said, “Without Sara’s determination and steadfast leadership, along with other Alliance of National Heritage Area board members and executives, the events of recent days would not have been possible. Thank you!”

Beyond that, Rivers of Steel extends our thanks to all of our partners throughout southwestern Pennsylvania and our friends and visitors who participated in our offerings throughout the year. The effort to get a bill through Congress to benefit our region is only an example of a behind-the-scenes saga of some of the work we do. You are the reason we are here and why we will never give up—applying our region’s legendary work ethic to whatever challenge arises. Each day, we work together to commemorate our industrial culture and history, making our communities stronger and building opportunities for future success.

Gita Michulka is a Pittsburgh-based marketing and communications consultant with over 15 years of experience promoting our region’s arts, recreation, and nonprofit assets.

Gita Michulka is a Pittsburgh-based marketing and communications consultant with over 15 years of experience promoting our region’s arts, recreation, and nonprofit assets.

Gita Michulka is a Pittsburgh-based marketing and communications consultant with over 15 years of experience promoting our region’s arts, recreation, and nonprofit assets.

Gita Michulka is a Pittsburgh-based marketing and communications consultant with over 15 years of experience promoting our region’s arts, recreation, and nonprofit assets.

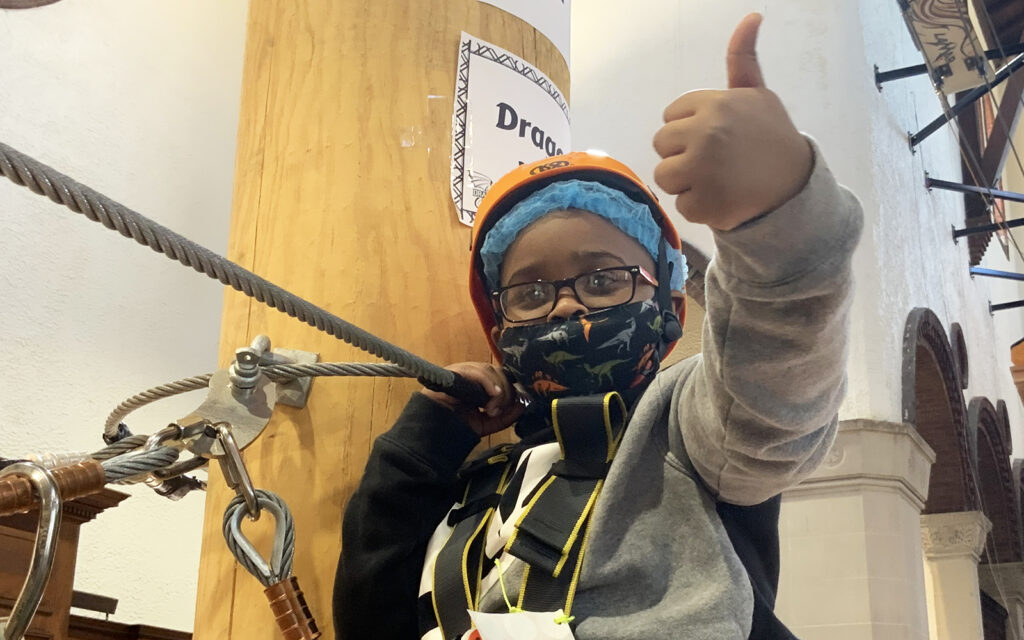

“It was an overall wonderful experience to work with the staff and students at Turtle Creek Elementary STEAM Academy,” said JaQuay Carter. “The young scholars were well prepared, thoroughly engaged, and very interested to learn about the process of making iron and steel. These were some of the brightest and best-behaved students I have ever had the pleasure of instructing. One lucky student per class got to try on heat safety gear and experience the clothing required to work at a blast furnace.”

“It was an overall wonderful experience to work with the staff and students at Turtle Creek Elementary STEAM Academy,” said JaQuay Carter. “The young scholars were well prepared, thoroughly engaged, and very interested to learn about the process of making iron and steel. These were some of the brightest and best-behaved students I have ever had the pleasure of instructing. One lucky student per class got to try on heat safety gear and experience the clothing required to work at a blast furnace.”