Exploring the Rivers of Steel National Heritage Area – By Water!

Exploring the Rivers of Steel National Heritage Area – By Water!

Enjoying the Beauty and Power of our Region’s Waterways

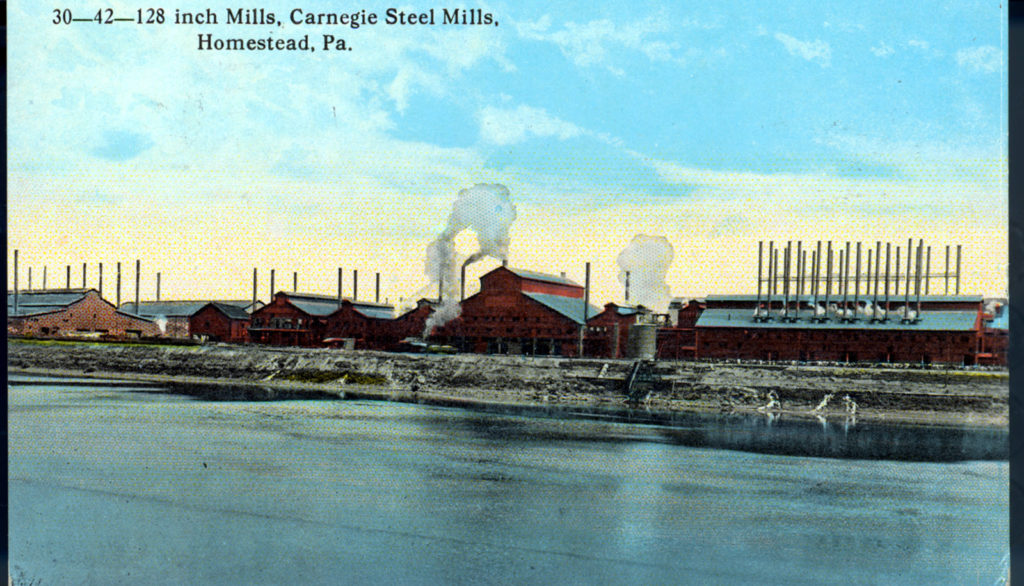

There are many ways to float your boat in the Rivers of Steel National Heritage Area. Centered around Pittsburgh, a city nestled between the Allegheny, Monongahela, and Ohio Rivers, the Heritage Area also encompasses the Beaver, Kiskiminetas, and Youghiogheny Rivers, which wind through early iron furnace ruins, coking ovens, patch towns, mill towns, main streets, machine shops, and endless tales of industrial innovations.

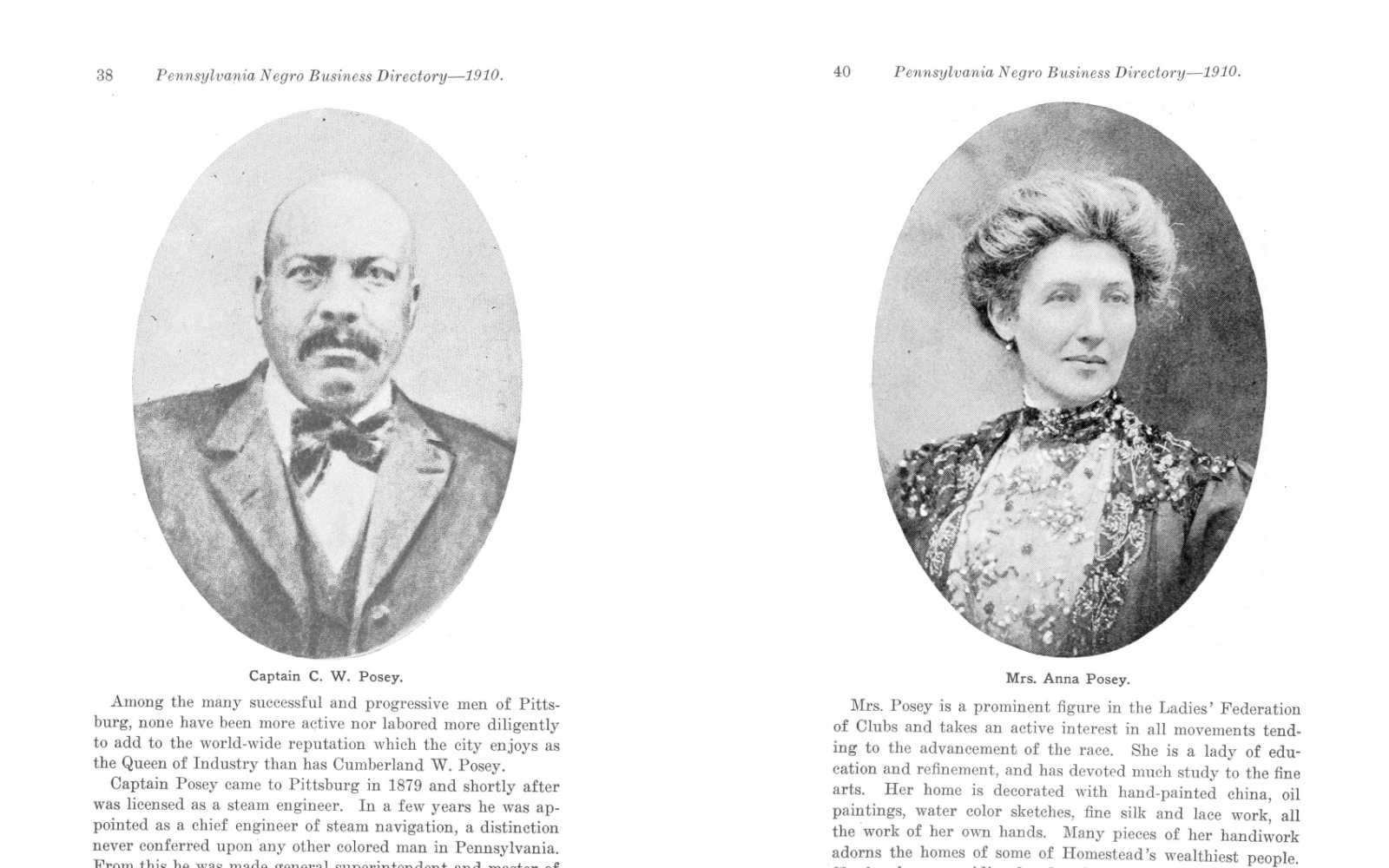

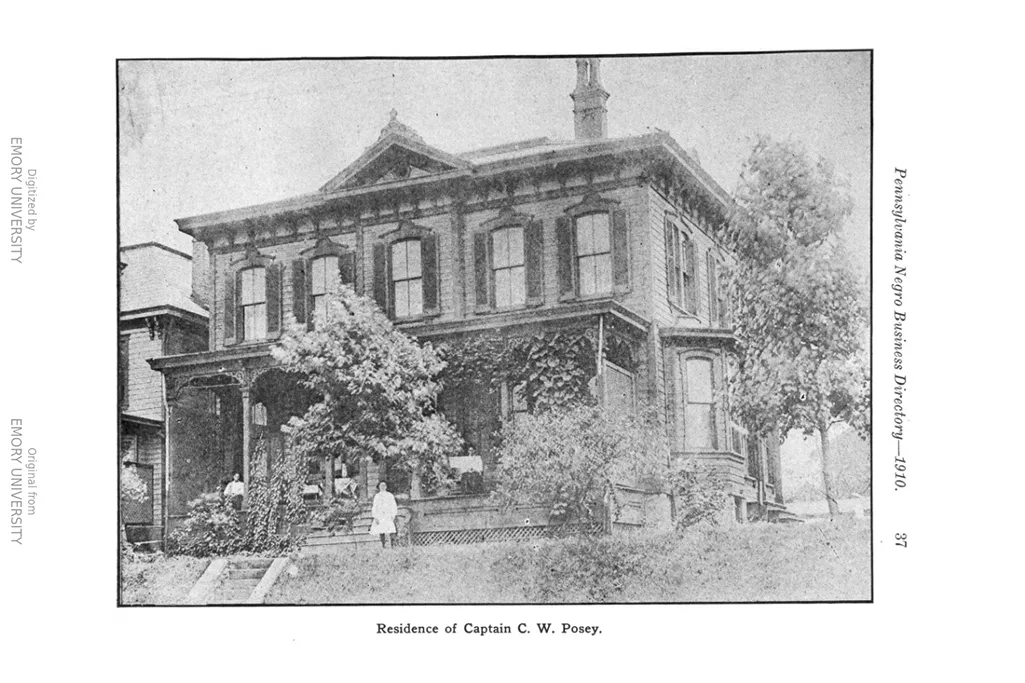

Below you’ll learn about ways to get on these rivers to enjoy their beauty and power, but first we’ll share the story of another remarkable local business leader from history who built a successful enterprise that relied on region’s waterways. When Pittsburgh’s industrial history is chronicled, white men are often at the center of the action. If you missed our recent post about Cumberland “Cap” Posey, a man born into slavery who blazed a trail to the same economic and social circles as the big names of the Gilded Age, click here to read more. And read on to learn the story of an immigrant woman, Mary Pattison Irwin, who thrived in the early republic. Both of these lesser-known entrepreneurs exemplify the vision, ingenuity, and agility that define this region’s industrial legacy.

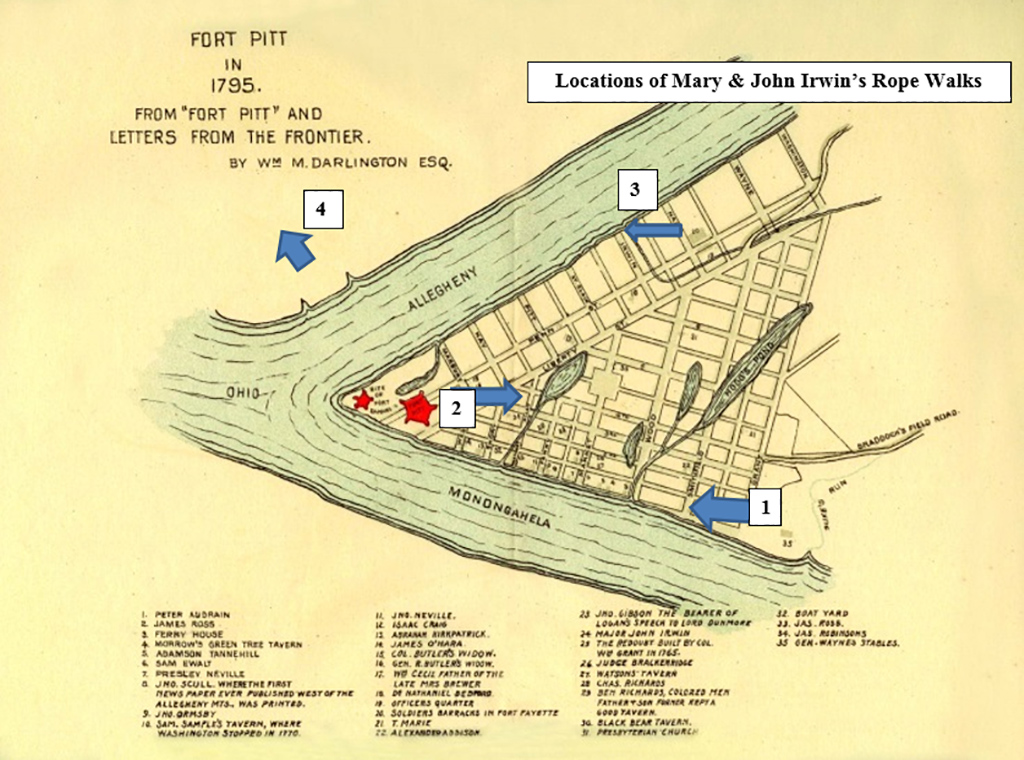

Map of Mary and John Irwin’s Rope Walk Locations

Mary Pattison Irwin

At a time when the focus was more on founding fathers than leading ladies, Mary Pattison Irwin forged her way to the height of business success by dominating Pittsburgh’s rope making industry. She had a pattern of taking her life into her own hands—as a thirty-year-old living in the north of Ireland, she convinced her parents that the family should attend Dublin’s inaugural St. Patrick’s Day Ball in 1784. It was a six-hour carriage ride to arrive at Dublin Castle, which put quite a distance between her and the doctor she was betrothed to but had recently rowed with. The luck of the Irish favored her at the ball, where she met Colonel John Irwin, a Revolutionary War hero who had fought alongside George Washington. The two were married within weeks and soon sailed to the newly-formed America, staking a claim to the land owed to John as a war veteran.

As they settled into a burgeoning Pittsburgh, their family grew by four children and it soon became clear that John’s war pension needed to be augmented. Mary reportedly took stock of her surroundings, saw three rivers, imagined the growing parade of boats that would be sailing on them, and determined that there would be a great need for rope. And so, the city’s first rope factory was started along the Monongahela River, officially registered as “John Irwin and Wife.” Women were rarely credited in professional capacities, so even this rather anonymous listing was a bold declaration of the role Mary played in the enterprise. The substantial injuries that John had suffered during the Revolutionary War likely limited his ability to assist with day-to-day operations. Despite her foresight of the demand for rope, Mary had no experience with the process of making it or in running a business, but diaries and letters indicate that she was at the helm.

Sadly, Col. John Irwin died shortly after the business got going, leaving Mary to care for four children under age twelve and manage the growing business on her own. One of her first orders of business was to rename the enterprise “Mary Irwin and Son”—law required that a man be listed on a company charter, so her twelve-year-old son John was looped in.

A long, narrow space—at least 1,000-feet long—called a ropewalk, was the hub where workers twisted hand-spun hemp strands into rope. Pittsburgh’s flat riverbanks suited the activity well. Two of the Irwin ropewalks burned down, and as the city and business grew, Mary relocated the operations three times to allow for expansion. Today Rope Way still exists on the North Side as a remnant of her business. If you’d like to see the traditional way of spinning rope, click here to read a WESA article about Mary that includes a video of the old rope walk in England’s Chatham historic dockyard.

Mary made it in a man’s world, and her rope—known for being waterproof—made its way into history. In 1803, when the Lewis & Clark Expedition outfitted itself in Pittsburgh before departing from a point on the Allegheny River where the Convention Center sits today, it is almost certain that they loaded up with rope sold by Mary—she was the only ropemaker listed in the city at that time. Her company made the rope used on the Steamboat New Orleans in 1811 as it set off to complete the first journey down the course of the Ohio and Mississippi Rivers. And in 1813, when Commodore Perry was preparing the U.S. Navy to take Detroit and Lake Erie back from British seizure in the War of 1812, he sought out Mary specifically to outfit his warships. If you’d like to learn even more about Mary and her family (Irwin Borough in Westmoreland County was named for her son John), follow the Pittsburgh Mayors Facebook page. It’s run by Gloria Forouzan, who discovered Mary’s story when she began researching the history of Pittsburgh’s mayors and other notable locals as Pittsburgh Mayor William Peduto’s office manager during the leadup to the city’s bicentennial celebration in 2016. Now retired, Gloria regularly shares newly uncovered information related to Mary’s story on that Facebook page. The What’s Her Name podcast also hosted Gloria for a very entertaining episode dedicated to Mary’s accomplishments.

Ways to Enjoy the Region’s Waterways

If you’re planning to hit the road on these itineraries during the global pandemic, please be mindful of the health and safety guidelines in place from the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Be sure to contact the sites, restaurants and attractions directly to confirm their operating statues and the safety protocols they have in place. We encourage you to bookmark these itineraries as travel inspiration to return to when things are less uncertain.

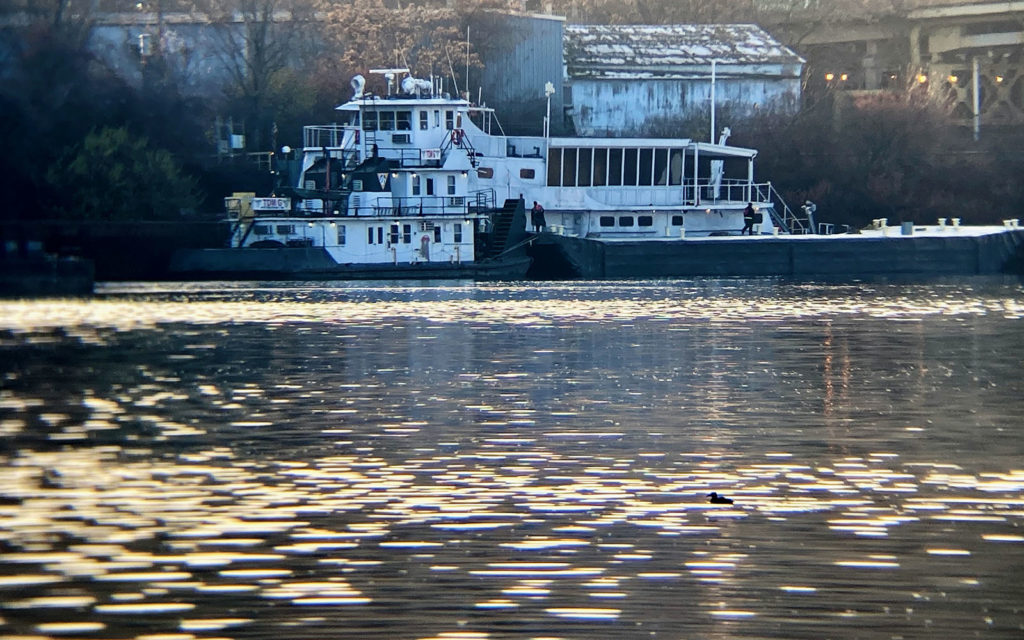

The Explorer riverboat viewed from Station Square with First Side in the background.

Rivers of Steel’s Explorer Riverboat

Rivers of Steel’s Explorer riverboat lives up to its name. Built as a floating classroom, this 94-foot vessel welcomes students for a slate of hands-on STEAM programming, offers thoughtful sightseeing tours, and is available for social and corporate event charters on the water. Docking on the North Shore at the headwaters of the Ohio, Explorer was the first commercial passenger boat to be built to LEED green building standards. It’s a place where students test the waters to draw conclusions about the health of the three rivers, learn about the artistry—and physics—of bridges and try their hand as a structural engineer, and see the places where history happened while cruising on the rivers that have defined the region.

Rivers of Steel’s sightseeing tours allow passengers of all ages to take in downtown’s shores and skylines from the best vantage point: Pittsburgh’s three rivers. Offered as a public tour in typical seasons, Rivers of Steel’s signature sightseeing cruise, PGH 101: An Intro to Innovation, reveals how the region’s wealth of natural resources and the character of its residents have shaped it into a dynamic city with a legacy of innovation, giving passengers a sense of the city’s history and current character while being surrounded by its natural beauty. During the pandemic, quarantine pods of up to 18 people can charter a private PGH 101 tour on Explorer—though usually the boat can accommodate up to 110. And whether you’re planning a celebration of a personal milestone, a corporate success, or the fact that Pittsburghers are embracing the beauty and vitality of their rivers, Explorer is the perfect venue on the water for intimate and engaging events.

Image courtesy of the Mon Valley Rowing Club

Boat Houses on the Three Rivers

Rowers cutting their oars through the water carve an elegant silhouette on the Allegheny, Ohio, and Monongahela Rivers. This low-impact, total body sport can be a solo pursuit or a team effort. Whether you’ve been rowing for years or want to take your first lesson, area boat houses offer an array of instructive programs for all ages.

- The Mon Valley Rowing Club in Charleroi was founded by a group of community members who aimed to turn an underutilized resource—the Monongahela River—into something that they saw as their greatest resource—children. Youth who attend high schools in the Mon Valley from Monongahela to Brownsville can join the Junior Rowing Program, with an emphasis on at-risk youth. Each child is paired with an adult committed to mentoring them on the water and in life. MVRC also has a Learn to Row summer program for adults.

- The Pittsburgh Rowing Club was started in 2008 by Florin Curuea, a rower with a number of personal and coaching accomplishments, including racing on the 2012 Romanian Olympic Rowing team. Youth and Adult teams row out of the Montour Marina Boathouse in Coraopolis on the Ohio River near Neville Island, where a variety of instruction options are available for different skill levels.

- Steel City Rowing develops its youth and adult members into athletes, leaders, and stewards of the region’s rivers. Learn to Row programs, summer camps, private lessons, and memberships are available for all ages and skill levels at the organization’s state-of-the-art, LEED-certified boat house on the Allegheny River in Verona.

- Founded in 1984, Three Rivers Rowing Association has grown into one of the largest community-based rowing and paddling clubs in the United States. The organization’s boat house on Washington’s Landing and the Millvale Training Center along the Allegheny River offer instruction, equipment, and programming for complete novices and lifelong rowers to glide through the water on a people-powered boat. In addition to rowing programs for all ages, Three Rivers Rowing Association also offers Dragon Boating activities for groups of 14 to 40 people in boats strikingly decorated to Chinese tradition, painted as a dragon to scare away evil spirits. Rowers paddle together to the beat of a drum.

Image courtesy of Kayak Pittsburgh.

Kayak Pittsburgh

If you’re hoping to get a bit closer to the water, Kayak Pittsburgh can make it happen. This kayaking rental concession owned and operated by Venture Outdoors has three locations in Allegheny County for a variety of scenic experiences: North Park Lake, or the Allegheny River on the North Shore and in Aspinwall. Single and tandem kayaks, along with stand-up paddle boards, are available for rent, and Venture Outdoors offers a regular slate of instructional classes, guided trips, and social paddles. In addition to kayaking, Venture Outdoors also offers guided canoeing and fishing programs.

Nautical Nature

Nautical Nature

Operated by the Moraine Preservation Fund, Nautical Nature is a 37-passenger enclosed pontoon boat that sail’s on Lake Arthur in Moraine State Park. Public tours showcase showcase the area’s natural history and osprey reintroduction, while taking in the scenery and wildlife of this beautiful spot in Butler County. The boat also offers environmental student programs and is available for private charters and dinner cruises on the lake. The Moraine Preservation Fund plans to launch and cruise a new Nautical Nature vessel in the spring of 2021.

Image courtesy of the Rivers Edge.

The Rivers Edge Canoe & Kayak

A family-owned canoe and kayak sales and rental store along the beautiful Kiskiminetas River in Leechburg, The River’s Edge Canoe and Kayak offers the gear, pointers, and inspiration you need for a scenic river experience in Armstrong County. Paddlers on the Kiski can expect to see wildlife in its natural habitat—there are a number of fish species, great blue herons, eagles, deer, and even the occasional bear! Owners Evelyn and Neil Andritz have curated several trip ideas to experience the best of the Kiski, and can point you to the best swimming spots, fishing holes, and dinner spots around. To soak in the experience even longer, Rivers Edge offers camping packages ranging from sites right along the river to a stay at Leechburg’s beautiful Old Parsonage B&B.

Image courtesy of SurfSUP.

Stand-Up Paddleboarding (SUP)

We might not be able to walk on water, but atop a stand-up paddleboard we can glide across its surface. Resembling a thick surfboard, a stand-up paddleboard (or SUP) provides a flat floating surface to stand (or sit or kneel) on with a paddle in hand to navigate the water.

- BVR Boardshop in Bridgewater offers stand-up paddleboarding (SUP) rentals on the Beaver River, about a mile from where it flows into the Ohio River. The company also offers SUP Yoga events throughout the warmer months.

- SurfSUP Adventures was established in 2011 with an eye on inspiring others to care for the region’s waterways and environment, and now has locations in Moraine State Park, Oakmont, Pittsburgh, and Johnstown. There are a variety of trip options, including serene eco-tours, invigorating “on-water” yoga practices, and adrenaline infused whitewater surfing adventures. SurfSUP sells and rents boards, paddles and equipment, and also offers team-building events, youth initiatives, and conservation programs that can be customized for all age and skill levels.

Courtesy of the Laurel Highlands Visitors Bureau

The Youghiogheny River

The Youghiogheny River is known for its rapids and the horseshoe curve it makes through the mall river town of Ohiopyle in Fayette County. When scouting a water route in 1754 that would allow the British to retake control of the Forks of the Ohio (present-day Pittsburgh) from the French, a young George Washington reached the 19-foot-wide Ohiopyle Falls of the Yough and made up his mind that the river was unnavigable. He called his troops back to the main road, and soon found themselves in a skirmish that would set the French and Indian War in motion—and lay the blame on Washington. More than 200 years later, in 1971, Ohiopyle river guide Tom Love innovated a new inflatable boat design that would prove Washington wrong on that “unnavigable” declaration. He crafted a high-performance raft without a metal frame called the Shredder that can be compactly folded and is self-bailing—important when the rapids are dumping a torrent of whitewater inside the boat. Love has a video of the first run of the Ohiopyle Falls he made on the Shredder—something Washington and his troops couldn’t do. Today, Shredders are favorites of seasoned paddlers around the world. You can read more about the Shredder from the Laurel Highlands Visitors Bureau’s feature.

While the thrill of the whitewater is certainly integral to the Yough’s character (there are class I – V rapids on the river), many are surprised to know that the Middle Yough offers an opportunity for a calm float trip to take in the history and natural beauty of this part of the Laurel Highlands. There are a number of outfitters in Ohiopyle that offer rentals, gear, guides, tours, and logistical support to those who want to enjoy the Yough—whether they’re beginners or veterans on the water, seeking serenity or thrills. Here is a sampling:

- Laurel Highlands River Tours and Outdoor Center has been getting folks of all ages on the Youghiogheny River since 1962. Guides and coaches can also get novices and veterans alike through the class III, IV, and V rapids on the Lower and Upper Yough that will get your adrenaline pumping, and rentals and guides are available for the calmer waters of the Middle Yough. The Laurel Highlands River Tours and Outdoor Center also offers a three-hour Express Tour on the class III/IV rapids of the lower Yough, so you’ll have time for high-flying adventure on the company’s zip line, guided mountain biking tours, rock climbing excursions, and gem mining activities. This outfit also operates the Yough Lake Campground near Ohiopyle, so the fun can last for days—and nights under the stars.

- Ohiopyle Trading Post & River Tours sends guided and unguided tours out on the Yough, and even has Shredders available. Outdoor enthusiasts of every stripe will find something to do at the Trading Post, which also offers kayaking and bike lessons, fishing trips, and refreshing scoops at the Kickstand Ice Cream Shop.

- White Water Adventurers offers everything you need for a whitewater getaway in Ohiopyle. This family-owned outfitter offers guided and unguided rafting trips on the Yough, along with bike rentals, Ohiopyle Mini Golf, and the Yough Plaza Motel in downtown Ohiopyle.

- Wilderness Voyageurs offers guided and unguided rafting trips on the waters around Ohiopyle – and several other rivers in Maryland and West Virginia. They also offer instructional outings for kayaking and fly fishing, along with stand-up paddle boarding. On their Historic Float Trip in Connellsville, PA, a guide dressed in 1750s garb joins you on your raft to spin a historical narrative that follows the French & Indian War, the Whiskey Rebellion, and the coal and coke industries in Western PA. The guide does all of the rowing on this tour, making it a great choice for seniors and young children. They also have a great history of the Youghiogheny River on their website, filled with interesting details and lots of reverence.

- The Laurel Highland Visitors Bureau has a full guide to the area’s water sports and whitewater rafting options.

Jump In!

When the water calls, you know what to do. Head to your local swimming hole, or roll up your pantlegs and wade through a nearby stream to get your feet wet. NextPittsburgh published a roundup of 10 great creeks to explore around Pittsburgh, and FITT staked out the best swimming holes near Pittsburgh.

If you missed them, be sure check out the Automobiles and Roadways itineraries, part one and part two, as well as the Trains and Tracks and the Planes & Aviation itineraries.

Stay tuned for more itineraries through the Rivers of Steel National Heritage Area, as we continue to explore the region through the lens of transportation.

Migratory Bird Sightings

Migratory Bird Sightings

Cultural Heritage Recipe Box: Winter Holiday Edition

Cultural Heritage Recipe Box: Winter Holiday Edition

Nautical Nature

Nautical Nature

About Zachary Rutter

About Zachary Rutter

Art for Everyone

Art for Everyone