Model Ts on the National Road’s Turkeynest Curve, heading down from the historic Summit Hotel. Courtesy of the National Road Heritage Corridor.

By Brianna Horan, Manager of Tourism & Visitor Experience

Exploring the Rivers of Steel National Heritage Area – Automobiles & Roadways, Part Two!

Exploring the Rivers of Steel National Heritage Area – Automobiles & Roadways, Part Two!

In part one of our Automobiles & Roadways itinerary, we explored Allegheny, Beaver, and Butler Counties. Today we’ll follow the National Road Heritage Corridor through Somerset, Fayette, and Washington Counties before hopping on the a historic stretch of the Lincoln Highway through Westmoreland County! Then we’ll close out this virtual journey with a trip through time at the Meadowcroft Rockshelter. But first, let’s take some inspiration from the “Four Vagabonds.”

The Summit Inn Resort, courtesy of the Laurel Highlands Visitors Bureau.

The Four Vagabonds

There’s a lot of talk lately about forming a “quarantine pod” with a few friends or family members—a small group of people who share similar interests and risk tolerances who get together to keep cabin fever at bay during the COVID-19 pandemic. Prepare to have squad envy: Back in the early 1900s, a foursome of recognizable men established an annual camping trip filled with escapades, innovations, and adventure. Henry Ford, Thomas Edison, Harvey Firestone, and naturalist John Burroughs gathered each summer from 1915 to 1924, and called themselves the “Four Vagabonds.”

The summer of 1918 brought the group together in Pittsburgh, before they set off to Hempfield and Connellsville as they travelled the National Road by car and camped in tents along their way to Maryland and West Virginia on a mountainous route. These titans of industry were legends of their day, and the press loved to follow their exploits every year. Local headlines included, “Electricity Wizard Edison Arrives in the City,” and “Ford Chops Wood; Edison Lights Camp,” according to 2018 Pittsburgh Post-Gazette article about a 100th anniversary commemorative Model T tour that retraced the original route through what today is known as Pennsylvania’s Laurel Highlands.

The group—along with a cook and photographer—spent their first night after leaving Pittsburgh in Miller’s Woods, which is now the Westmoreland Mall. The next day on the road, a fan blade went through the radiator of one of the group’s Model T’s in Connellsville. Who better than Henry Ford himself to have around when there are car troubles? He fixed the issue, but the delay and poor weather prevented the group from making it to their campsite that night. Instead, they spent a memorable evening at the Summit Hotel in Farmington, known today as The Historic Summit Inn Resort—where you, too, can enjoy an enjoyable stay with friends. The six-foot tall mantel that the Vagabonds took turns kicking cigars off of is still there, and so are the steps where they had a stair jumping contest! (Ford won, bounding the ten steps in two leaps.)

The Summit Inn is so named because it rests at the top of Summit Mountain of the Chestnut Ridge, its grand porch offering views for miles. The grueling climb was a perfect opportunity to test how Firestone’s tires worked on Ford’s cars. You and your road-tripping companions will also delight in the winding roads and scenic vistas throughout the southern stretch of the Rivers of Steel National Heritage Area that lead to historic roadways. And if you’re waiting a while to hit the road, you can live vicariously through photos and recollections recorded by Vagabond John Burroughs in Harvard’s Library Collection blog, The Shelf. A sure sign that the trip ahead is going to be a good one: “It often seemed to me that we were a luxuriously equipped expedition going forth to seek discomfort.”

If you’re planning to hit the road on these itineraries during the global pandemic, please be mindful of the health and safety guidelines in place from the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Be sure to contact the sites, restaurants and attractions directly to confirm their operating status and the safety protocols they have in place before you go. We encourage you to bookmark these itineraries as travel inspiration to return to when things are less uncertain.

National Road Wagon Train entering Addison, PA by Charlotte Pletcher, courtesy of the Laurel Highlands Visitors Bureau.

The National Road Heritage Corridor

Driving through the National Road Heritage Corridor as it tears across the southwestern corner of Pennsylvania means following a patchwork of trails first worn by Native Americans and migrating buffalo, tracing a chronicle of historic events that were integral to the founding of the nation, and traveling an eye-opening journey through the shaping of American culture. Today it’s marked on maps as Route 40 amidst a tangle of other highways and traffic arteries, but when President Thomas Jefferson signed legislation to construct what was then the Cumberland Road, it was the singular–and first–federally-funded highway to link multiple states. Originally named for its eastern terminus, the National Road begins in Cumberland, MD, and then crosses six states to end in Vandalia, IN. The first segment of the road, between Cumberland and Wheeling, WV, is known as the Eastern Legacy, and was completed from 1811 and 1820. But the highway’s history and influence reach much wider than that timespan. The National Road Heritage Corridor has a detailed timeline of important events and list of sites to visit on its website, but below are a few of the Pennsylvania highlights that put the National Road on the map!

Fort Necessity Visitors Center, courtesy of the Laurel Highlands Visitors Bureau.

George Washington Carves a Path and Starts a War

George Washington spent a lot of time in southwestern Pennsylvania as a young officer of the British army. In 1753, he was sent into the Ohio Country (present-day western Pennsylvania and eastern Ohio) with orders to deliver a diplomatic message to the French ordering them to evacuate the area. The French had already begun to erect forts in what the British viewed as their territory, and 21-year-old Washington returned to Virginia to report that the French had politely told Washington they would not obey his commands to leave.

The future first president was then ordered back to the Ohio Country, this time as a newly commissioned lieutenant colonel overseeing a regiment of men ordered to build a road to present day Brownsville, PA, to help defend a small fort that the British had built at the forks of the Ohio River (today Pittsburgh’s Point State Park). Before he’d reached his destination, Washington learned that the French had overtaken the British stockade and built Fort Duquesne on the prized piece of land where the three rivers met. While waiting for further orders, Washington and his men were involved in a skirmish that left 13 Frenchmen dead—including the leader of their detachment, Ensign Josephe Coulon de Jumonville—and no clear picture of who fired the first shot. Explanations were lost in translation, and Washington eventually ended up signing a document that placed the blame on him. This would become the catalyst for the French and Indian War. In the meantime, Washington and his men scrambled to build Fort Necessity out of… necessity. A battle occurred there soon after that left more British casualties than French and Indian losses, and Washington and his men marched back to Virginia as Fort Necessity burned.

Taking things more seriously, the British sent Major General Braddock to North America with two regiments of infantry and a plan to simultaneously attack numerous French forts in the New World. George Washington joined the campaign as a volunteer aide to General Braddock – and for more road building. It was grueling, slow work to widen and extend Washington’s original road (which often followed Native American foot paths) to accommodate large wagons and artillery. Braddock forged ahead with Washington and half of the troops, finally confronting the French and Indians in a wilderness battle in what is today Braddock, PA, about 10 miles from Pittsburgh’s Point. The British losses were tremendous, and a severely wounded General Braddock was carried off the field as they retreated back to the slower-moving half of the regiment. At an encampment about a mile west of the site of Fort Necessity, Braddock died on July 13, 1755. His men buried him in the road they’d been building, and then marched over the grave as they retreated further East to obliterate evidence of it to prevent the enemies from desecrating it. Braddock’s Road would later become a foundational part of the National Road.

The Washington’s Trail driving route begins on the National Road in tracing Washington’s first military ventures—and follies—throughout western Pennsylvania. The National Road section of the trail includes a number of fantastic sites to visit to experience this history. Fort Necessity National Battlefield features an interactive education center that brings to life Washington’s first military battle and the events that ensued, along with the development of the National Road. The National Park Service site also has a re-creation of Fort Necessity, along with walking paths that trace remains of the original Braddock Road. You can also visit Jumonville Glen and Braddock’s Grave nearby. If you don’t mind straying a bit from the National Road, Fort Ligonier in Ligonier, Braddock’s Battlefield History Center in Braddock, and the Fort Pitt Museum at Point State Park in Pittsburgh all tell fascinating pieces of this world-shaping history.

Stone House Restaurant, courtesy of the Laurel Highlands Visitors Bureau.

A Road is Forged Westward

The completion of the National Road to Wheeling in 1818 opened up the Ohio River Valley and the Midwest for settlement and commerce. Thousands of travelers headed west over the Allegheny Mountains, prompting small towns to pop up along the way with the National Road as their Main Streets. Hopwood, Uniontown, Brownsville, Washington, and West Alexander are all examples. Their positioning allowed them to become hubs of business and industry, and they still boast charm and intrigue for travelers who visit today. Picturesque Eberly Square in Uniontown even features full-sized bronze sculptures of Thomas Jefferson and Albert Gallatin planning the National Road. Gallatin was the first person to suggest the plan for building the National Road; the square is named in honor of Robert Eberly, a Fayette County philanthropist. The National Road Heritage Corridor has mapped out a Sculpture Tour along the Pennsylvania stretch of Route 40.

Taverns also opened up along the way to serve as a resting place for stagecoaches and their travelers. Mount Washington Tavern was built in the 1830s along the National Road and in the “backyard” of Fort Necessity. Furnished rooms and interpretive signs inside show visitors where men would drink and socialize in the barroom while women and children relaxed in the parlor. There’s a kitchen, dining room, and dormitory bedrooms, as well. At The Historic Stone House Restaurant & Inn, you can stop in for a delicious meal and even spend the night at an original wayside tavern of the National Road, just as travelers have been doing since it opened in 1822. In that time, many travelers were seeking the health benefits of the nearby Fayette Springs.

The 1830s saw the Federal Government transfer ownership of the National Road to the states through which it passed, at which point it became known as the National Pike. This gave states the opportunity to erect toll houses to collect fees from the large number of travelers along the road; Pennsylvania constructed six toll houses at 15-mile intervals along its 90-mile segment of road. Two stand today: Petersburg Tollhouse in Addison, Somerset County, and the Searight Toll House in Uniontown. They were in use until the turn of the 20th century.

Railroads would eventually put stagecoaches out of business, but these historic taverns and toll houses offer a view into the past. The invention of the automobile revived the National Road, which became US Route 40 in the 1920s. It was a major east-west artery until the modern interstate system was created in 1956 by the Federal-Aid Highway Act, diverting a lot of the traffic to Highways 70 and 68. The National Road was designated a National Historic Civil Engineering Landmark in 1976, and a State Heritage Park in 1994. Along the 90 miles of road in Pennsylvania, 79 sites have been deemed eligible for listing on the National Register of Historic Places.

The Laurel Highlands Visitors Bureau offers more itinerary inspiration with a four-day, three-night trip called All Along the National Road.

The famed Seven-Mile Stretch of the Lincoln Highway, courtesy of the Lincoln Highway Heritage Corridor.

The Lincoln Highway

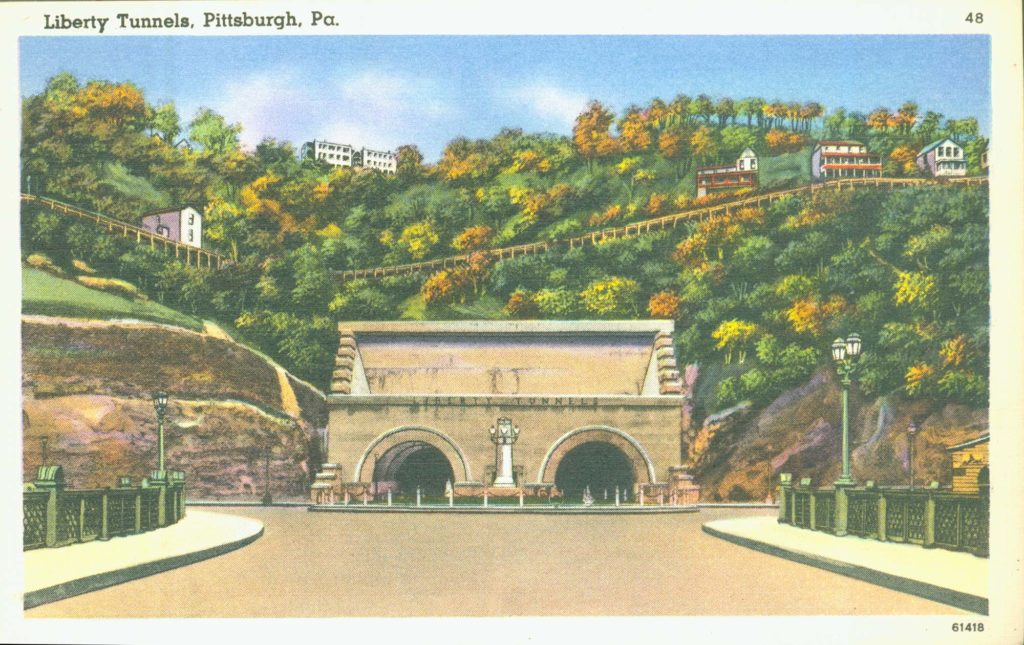

Another monumental roadway winds through the region—though this one goes from coast to coast, stretching from New York City to San Francisco! The Lincoln Highway opened in 1913, and was completed in 1925. This feat of feat of infrastructure gave Americans somewhere to go as the price of cars became more affordable. An entire car culture grew up along the roadway, with shiny new filling stations, tourist cabins, motor courts, restaurants, and tourist attractions—plus post cards to document it all for the folks back home. In Pennsylvania, where much of the Lincoln Highway is known as Route 30, the highway stretches across the southern part of the state. Two hundred miles of the road is designated as Pennsylvania’s Lincoln Highway Heritage Corridor, running between Abbottstown in the east, and Irwin in the west. A drive along this two-lane road is best enjoyed at a meandering pace, but the quirky roadside structures, vintage diners, and scenic views put the nostalgia factor in overdrive.

The Lincoln Highway Experience in Latrobe, PA, courtesy of the Laurel Highlands Visitors Bureau.

The Lincoln Highway Experience

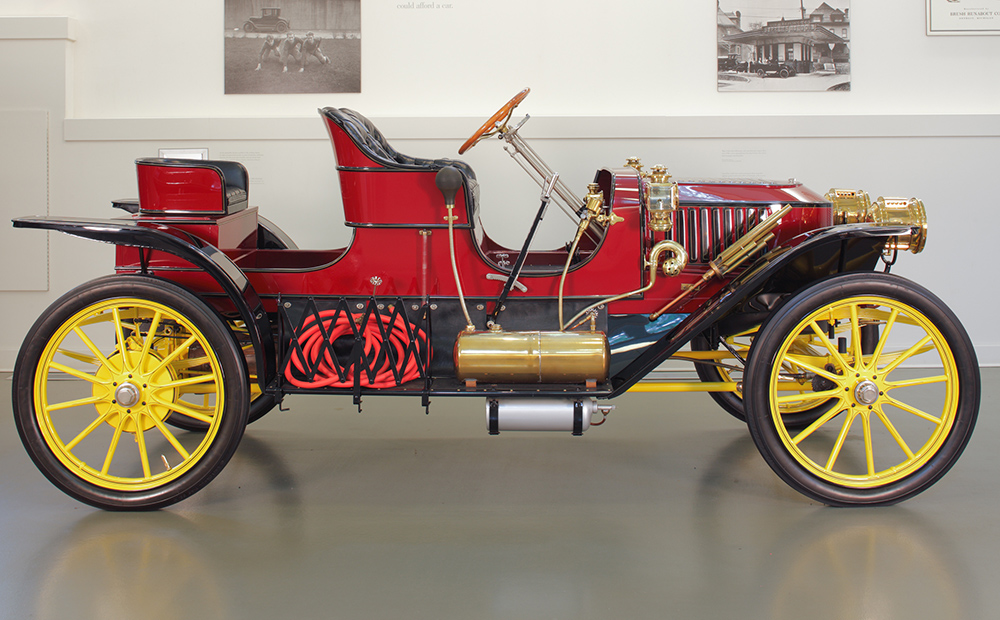

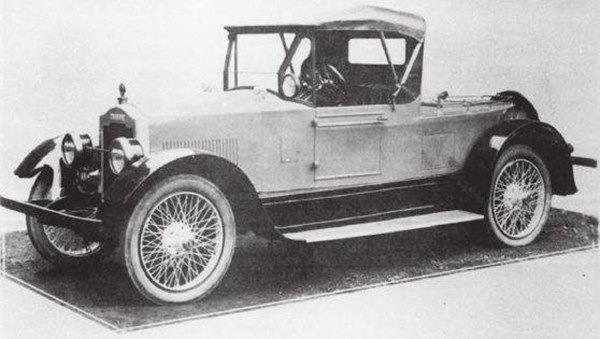

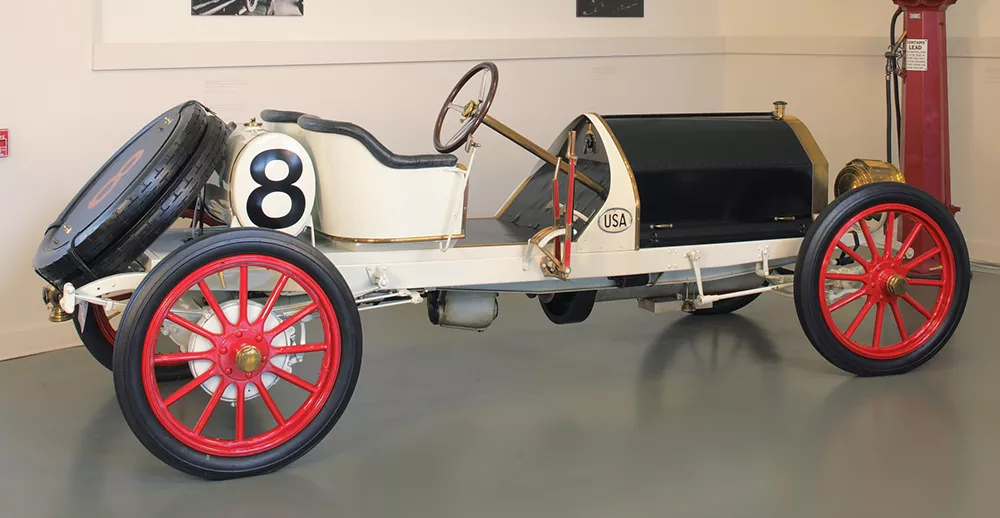

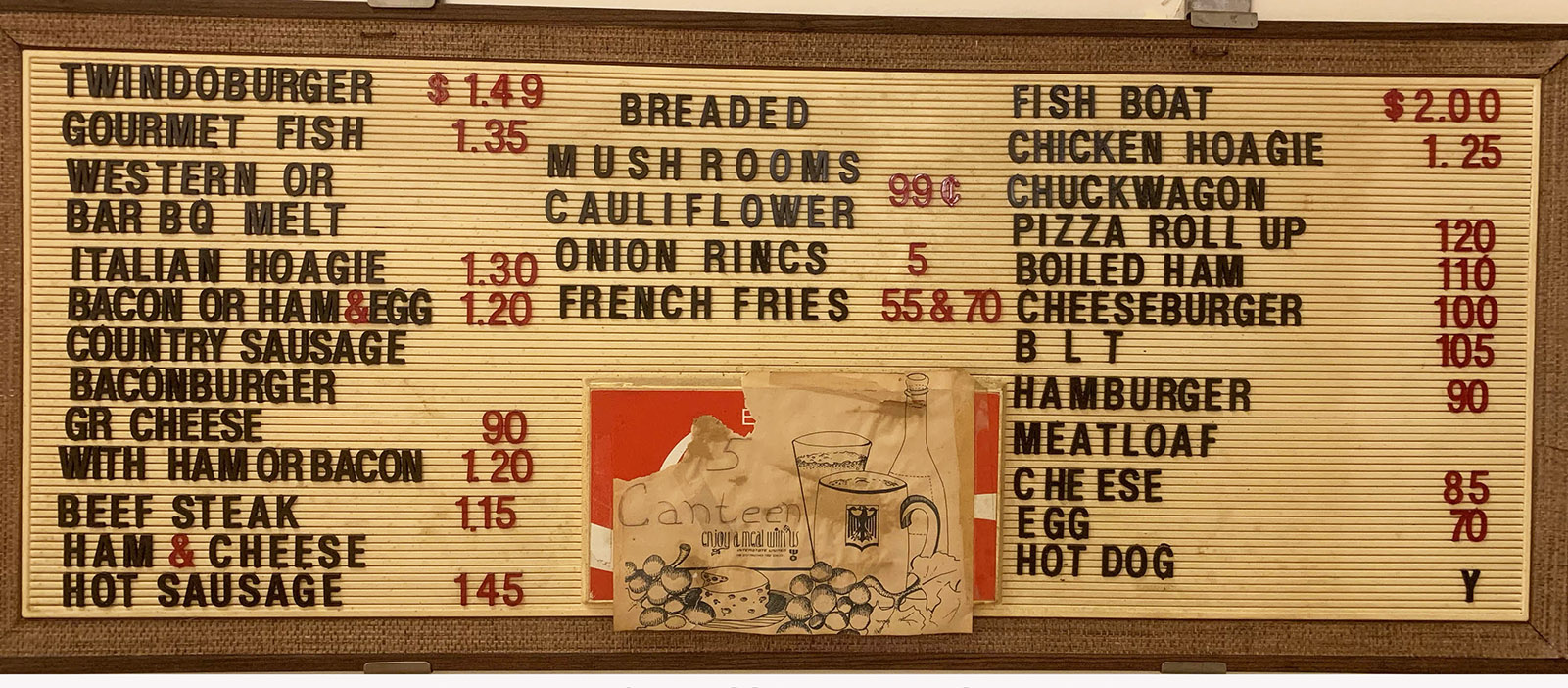

In Latrobe, The Lincoln Highway Experience brings all of that to life in one place at the largest museum in the country dedicated to the transcontinental roadway. Visitors can watch a short, award-winning video called “Through the Windshield” to learn about the 100+ years of history of the Lincoln Highway. There are interactive exhibits, including an authentic tourist cabin, an antique Packard, and a gas station from earlier times. The tour keeps getting better—it ends with a slice of pie and cup of joe, served in the gloriously-restored Serro’s Diner, a local establishment that operated between 1938 and 1990.

The Original Pie Shoppe

The Lincoln Highway inspired Americans to see the country, and you should too! Some signature sites in the region on Route 30 include The Original Pie Shoppe in Laughlintown, which was opened in 1947 by former World War II Navy cook Melvin Columbus and his mother Mildred, who had previously baked and cooked for guests of her boarding house. The cinnamon roll recipe used at the bakery is the one Melvin created using the rations supplied on his battleship! In addition to sweets, The Original Pie Shoppe also sells lunch items.

Compass Inn Museum & Ligonier Valley Historical Society

The Compass Inn Museum & Ligonier Valley Historical Society tells a different story of transportation of days gone by. Docents in period dress guide visitors on a tour of this authentically restored stagecoach stop in Ligonier, which opened in 1799 as a rest stop for wagoners and drovers taking animals to market. The completion of the Philadelphia Pittsburgh Turnpike in 1817 brought a steady flow of stagecoach traffic to the inn, which was used as a stop until 1862. At that point, railroads and canals were making stagecoaches obsolete. Today the inn is restored to its 1820 days, and features a serving kitchen, a ladies’ parlor, and four bedrooms. Three outbuildings have also been reconstructed, and the barn features an authentic stagecoach and Conestoga wagon.

The Road Toad

As you travel down the Lincoln Highway through Ligonier, The Road Toad restaurant’s sign is sure to catch your eye. A handsomely dressed amphibian waves his hat at drivers as he steers his antique automobile, beckoning you in to enjoy a meal. This stop is right off the road, but the dining room overlooks woods and the beautiful Loyalhanna Stream—delivering a respite into nature while you refuel and relax.

Brush Creek Cemetery

As you drive through Irwin, be sure to tip your own hat to a fellow auto enthusiast as you pass by Brush Creek Cemetery, just off of Route 30. George Swanson, who was a local beer distributor and World War II veteran, was buried inside his beloved 1984 Corvette—just as he always said he would be. Mourners at his 1994 funeral watched as an urn with his ashes was placed in the driver’s seat of the ‘Vette, which was then lowered by crane into the ground while Swanson’s favorite song, Engelbert Humperdinck’s “Release Me,” played from the cassette player.

Big Mac Museum

Just a few minutes away is the Big Mac Museum, celebrating a roadtrip staple that was invented right here in southwestern Pennsylvania! Jim Delligatti first served this now world-famous sandwich at his McDonald’s restaurant in Uniontown in 1967. Today the Big Mac Museum in North Huntingdon is conveniently located just off of Route 30, making it an easy stop to pay homage to the double-decker Big Mac. Inside is a fully functioning McDonald’s, and an area with displays and classic memorabilia—including a 14-foot-tall replica of the burger to snap a photo with! A stop here will satisfy your hunger, and will likely leave you with a certain jingle stuck in your head when you get back on the road…

A stagecoach rolling through a town in Washington County, Pa. Courtesy of Meadowcroft Rockshelter and Historic Village.

Meadowcroft Rockshelter and Historic Village

A visit to the Trails to Trains exhibit at Meadowcroft Rockshelter and Historic Village explores the evolution of transportation over 19,000 years in southwestern Pennsylvania, using five different vehicles from the collections. Learn about the foot power that our prehistoric predecessors used to traverse the rugged terrain surrounding the Meadowcroft Rockshelter, and compare that with the Conestoga wagons and stagecoaches that sped things up as the National Road was established. Transportation was revolutionized again when the development of railroads cut a path through many rural Pennsylvania farmsteads. On display is a Conestoga wagon built in 1837 in Cadiz, OH by wagonmaker Samuel Amspoker. Designed to transport heavy loads of freight across mountain ranges, these vehicles were named for the Conestoga River Valley in Lancaster County where they were first produced. Meadowcroft’s blog post, Transportation Through Time, explores how each advance in technology brought conveniences and complexities.

Stay tuned for more itineraries through the Rivers of Steel National Heritage Area, as we continue to explore the region through the lens of transportation.

Exploring the Rivers of Steel National Heritage Area – Automobiles & Roadways, Part Two!

Exploring the Rivers of Steel National Heritage Area – Automobiles & Roadways, Part Two!

About Steven Haines

About Steven Haines

Pittsburgh and the Automobile Industry in the Early 20th Century

Pittsburgh and the Automobile Industry in the Early 20th Century

Preservation Work on the #101 Locomotive

Preservation Work on the #101 Locomotive It was interesting to work through the layers of paint, discovering three different paint schemes used by US Steel over the years. We worked our way down to bare metal. The body was in good shape for the most part. The were some rust and holes around the sand boxes. The sand had accumulated moisture and rotted through the outside sheeting. Those areas will be covered with sheet metal patches and the missing roof hatch covers will be replaced at the same time. Because bare metal will quickly rust, Rivers of Steel provided primer to cover it. Each section was painted as the rust was removed. When the painting was completed, we stood back to admire the now renamed “Miss Carrie” in her new red dress.

It was interesting to work through the layers of paint, discovering three different paint schemes used by US Steel over the years. We worked our way down to bare metal. The body was in good shape for the most part. The were some rust and holes around the sand boxes. The sand had accumulated moisture and rotted through the outside sheeting. Those areas will be covered with sheet metal patches and the missing roof hatch covers will be replaced at the same time. Because bare metal will quickly rust, Rivers of Steel provided primer to cover it. Each section was painted as the rust was removed. When the painting was completed, we stood back to admire the now renamed “Miss Carrie” in her new red dress.

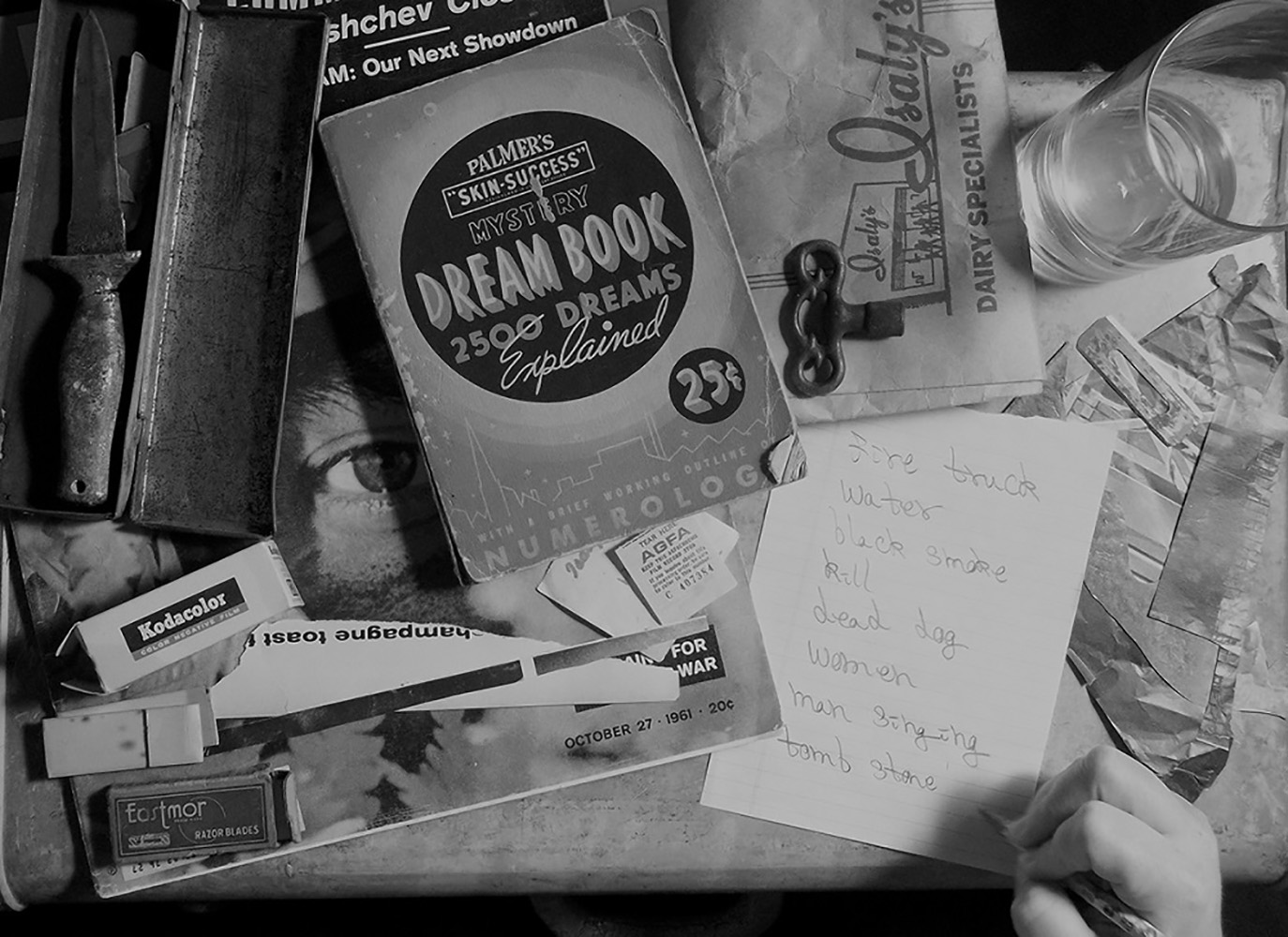

To Collect, Preserve, Display & Share

To Collect, Preserve, Display & Share When Rivers of Steel first put out the call for donations decades ago, the community responded with overwhelming support. Our archive has had the good fortune to receive the support of local organizations and businesses, dozens of former industrial workers, and a number of dedicated longtime donors, some of whom have made thousands of individual donations. We have managed to unearth truly incredible items: an exceptionally vibrant series of

When Rivers of Steel first put out the call for donations decades ago, the community responded with overwhelming support. Our archive has had the good fortune to receive the support of local organizations and businesses, dozens of former industrial workers, and a number of dedicated longtime donors, some of whom have made thousands of individual donations. We have managed to unearth truly incredible items: an exceptionally vibrant series of  Not only has Rivers of Steel created an archive that safely houses over 50,000 unique items, but it also makes these collections open to the public. Our archive is free to access by appointment, and almost any of the items in our collection can be viewed in person with a few exceptions. Additionally, portions of our collection are frequently displayed in our exhibition rooms on the third floor of the Bost Building. We have created a number of exhibits honoring the industrial and cultural heritage from southwestern Pennsylvania, with past shows focusing on topics like Jones and Laughlin Steel, the Little Steel era, folk art from around the region, industrial photography, and our

Not only has Rivers of Steel created an archive that safely houses over 50,000 unique items, but it also makes these collections open to the public. Our archive is free to access by appointment, and almost any of the items in our collection can be viewed in person with a few exceptions. Additionally, portions of our collection are frequently displayed in our exhibition rooms on the third floor of the Bost Building. We have created a number of exhibits honoring the industrial and cultural heritage from southwestern Pennsylvania, with past shows focusing on topics like Jones and Laughlin Steel, the Little Steel era, folk art from around the region, industrial photography, and our  Even during the current Covid-19 crisis, Rivers of Steel is working to facilitate access to our archives as safely as possible. While we are not currently receiving visitors to the archive, our staff is more than happy to work with researchers, students, and community members to access our collections online and to fulfill requests as best we are able. Our collections can be searched in

Even during the current Covid-19 crisis, Rivers of Steel is working to facilitate access to our archives as safely as possible. While we are not currently receiving visitors to the archive, our staff is more than happy to work with researchers, students, and community members to access our collections online and to fulfill requests as best we are able. Our collections can be searched in

About Shane Pilster

About Shane Pilster

Understanding Historic Preservation in a Dynamic Frame: The Graffiti Arts Program at the Carrie Blast Furnaces

Understanding Historic Preservation in a Dynamic Frame: The Graffiti Arts Program at the Carrie Blast Furnaces Graffiti Art Tours: Including the Whole History

Graffiti Art Tours: Including the Whole History I attended one of the Urban Art workshops on August 16, 2019. In it, Shane covered his relationship to the site and history as a writer, he was complemented by another Rivers of Steel staff member who provided more detail on the industrial history, and used the works at the site to educate visitors on the history of graffiti and how to understand and read different elements (e.g. dissecting what constitutes a tag, a throw up, a burner/masterpiece).

I attended one of the Urban Art workshops on August 16, 2019. In it, Shane covered his relationship to the site and history as a writer, he was complemented by another Rivers of Steel staff member who provided more detail on the industrial history, and used the works at the site to educate visitors on the history of graffiti and how to understand and read different elements (e.g. dissecting what constitutes a tag, a throw up, a burner/masterpiece). Stef Skills reflected on how even extreme changes to landscape can be slowly repaired by the march of nature. She connected this idea to larger indigenous movements to protect water and land (she had been part of protests at Standing Rock and camped in solidarity with the water protectors, integrating themes from her Standing Rock experience into a number of her previous pieces). Wes and Orion were more interested in the scale of the site, and the strength of the workers. Devine, a more old-school style writer, was interested in the history of the trains passing by the site—as trains are a crucial surface for graffiti practice. Stef suggested that they use the design of a series of train cars, and each artist would have his or her own “car,” but that there could still be some shared concepts.

Stef Skills reflected on how even extreme changes to landscape can be slowly repaired by the march of nature. She connected this idea to larger indigenous movements to protect water and land (she had been part of protests at Standing Rock and camped in solidarity with the water protectors, integrating themes from her Standing Rock experience into a number of her previous pieces). Wes and Orion were more interested in the scale of the site, and the strength of the workers. Devine, a more old-school style writer, was interested in the history of the trains passing by the site—as trains are a crucial surface for graffiti practice. Stef suggested that they use the design of a series of train cars, and each artist would have his or her own “car,” but that there could still be some shared concepts. Her work attempts a kind of site specificity: creating an explicit dialogue between the work of art, the site, and their audiences. The site shaped her work energetically due to its haunted character. She explained: “… it was overwhelming. It was really, really, dope…just something in the atmosphere there was like a ghost city kind of because so many people were in there at one point, that space was up and living. Hardcore. All day and all night. So to be there now where there was [almost] nobody there it was a little like tripped out” (2019).

Her work attempts a kind of site specificity: creating an explicit dialogue between the work of art, the site, and their audiences. The site shaped her work energetically due to its haunted character. She explained: “… it was overwhelming. It was really, really, dope…just something in the atmosphere there was like a ghost city kind of because so many people were in there at one point, that space was up and living. Hardcore. All day and all night. So to be there now where there was [almost] nobody there it was a little like tripped out” (2019). Like Bel2, Kart points to the role of labor as well as international flows, and the kind of energetic traces that remain in the space. He also emphasizes how graffiti is part of the industrial and postindustrial identity of the space since it became a site for guerilla intervention in the 1990s and also an ideal spot for watching painted freight trains pass.

Like Bel2, Kart points to the role of labor as well as international flows, and the kind of energetic traces that remain in the space. He also emphasizes how graffiti is part of the industrial and postindustrial identity of the space since it became a site for guerilla intervention in the 1990s and also an ideal spot for watching painted freight trains pass.

About Rachel Sager

About Rachel Sager