The Iron Pour and Metal Arts Crew

The spirit of the festival takes its inspiration from the iron-making legacy of this National Historic Landmark—embodied by a deftly orchestrated iron pour featuring Rivers of Steel’s metal arts crew.

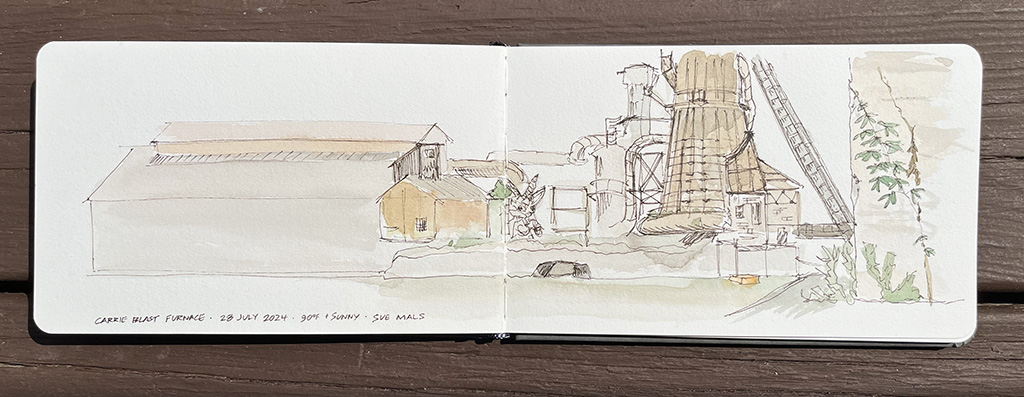

“The iron pour is the heart of the festival,” said Chris McGinnis, senior director of programs & regional partnerships. “It’s quite a sight to see! And artists from all over the world come to this National Historic Landmark site to participate in the iron pour. They arrive at the beginning of the week to create the molds that are cast during the festival. The process uses a cupola-style furnace, which is a scaled-down version of the process that had been used to produce iron by the hulking Carrie Blast Furnaces.”

Insider Tip: Make sure to arrive before 6:00 p.m. to guarantee that you’ll see part of the iron pour. The event may extend past 6:00 p.m., but they could finish their work early!

“Our largest operating furnace is capable of tapping up to 1,000 pounds of iron each tap. Our metal arts staff, who lead the iron pour, are skilled metal artists and craftsmen with a combined 40+ years of experience in foundry work. Our iron pours require 20 to 30 participants to manage all aspects of the operation,” McGinnis said.

“The metal-casting community nationwide is a close-knit group of enthusiasts,” McGinnis continued. “They often travel to numerous locations each year to participate in iron-casting projects, large and small. As the program has grown at Rivers of Steel, the Carrie Furnaces have become one of those destinations, joining established metal-casting hubs like Sloss Furnaces in Alabama; Salem Art Works in Salem, New York; and the Metal Museum in Memphis; among others.”

One of the artists joining in is Jay Elias. Elias runs the Evolution Arts Studio in Detroit, Michigan—a studio that uses the metal-casting process as a form of therapy, focusing on veterans and formerly incarcerated individuals. As a veteran, Elias struggled with post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and found a recovery process through art and metal working. He interned with Rivers of Steel this past summer and developed work focused on his experiences battling PTSD. His studio thrives on the holistic approach of art and therapy and offers free workshops for veterans. Be sure to check out his newly installed sculpture “Unfinished Business” located in the Iron Garden this year!

For those enticed by hot metal who would like to have a more personal experience, aluminum pours will also take place. As part of their Festival of Combustion experience, event-goers can carve a scratch mold, which is then cast—transformed into a glistening square of aluminum art! Guests spend a few minutes carving a creative design and then watch as molten aluminum is poured into the molds. After it cools, they have an artistic souvenir to take home. Insider Tip: The aluminum pours happen between 1:00 and 6:00 p.m., or until the scratch molds are gone, so stop by earlier in the day!

Insider Tip: Don’t miss out on a walk through the Iron Garden. Stop in before 6:00 p.m.—Penn State Master Gardeners, interpretive iron plaques, and text panels for the sculptures all offer ways to learn more about the natural garden.

Casting the Iron Garden

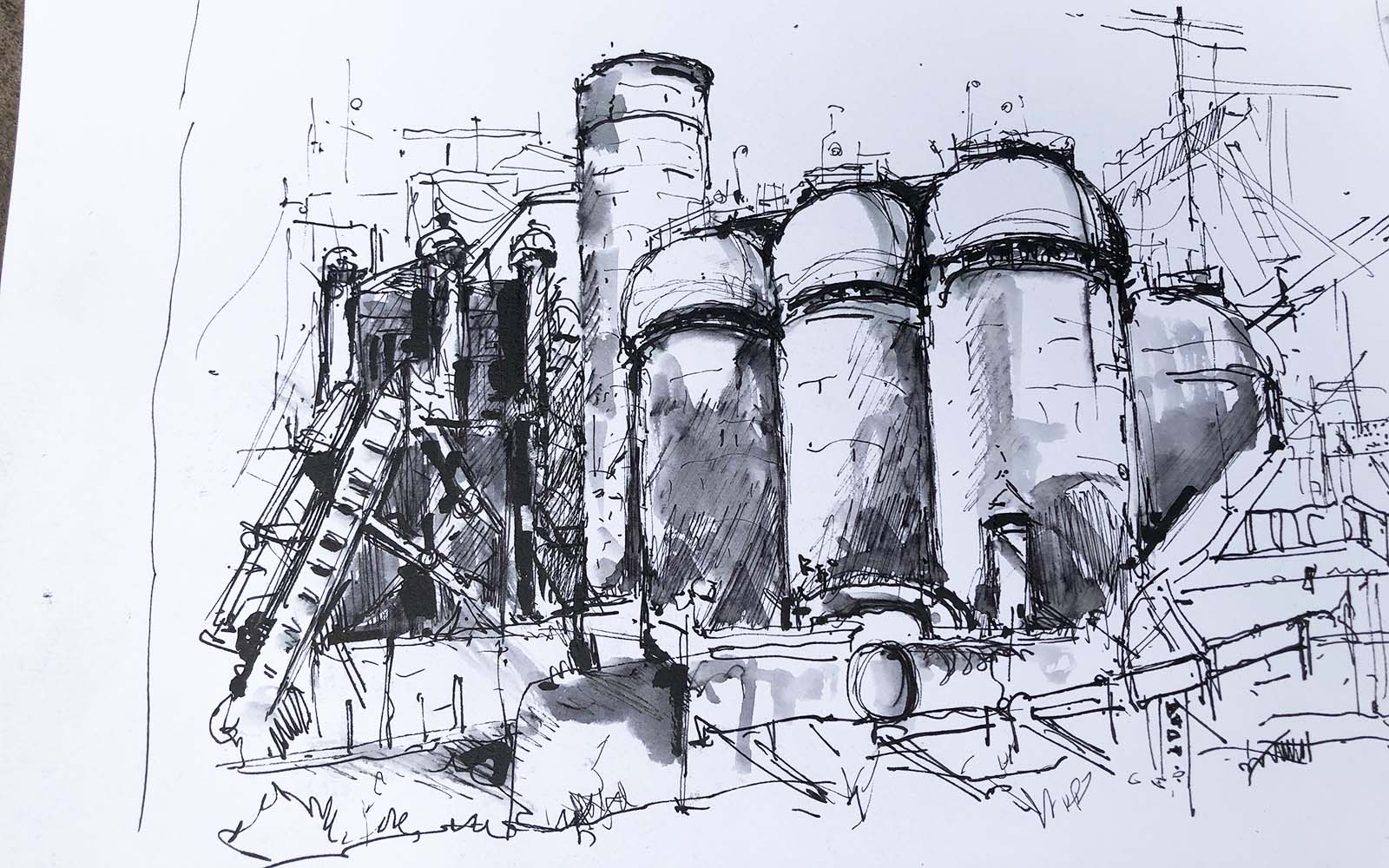

In October of 2014, something momentous happened. For the first time in more than 30 years, iron was created at the Carrie Blast Furnaces. The event was called Casting the Iron Garden, and now, ten years on, Rivers of Steel is celebrating this anniversary as part of the Festival of Combustion.

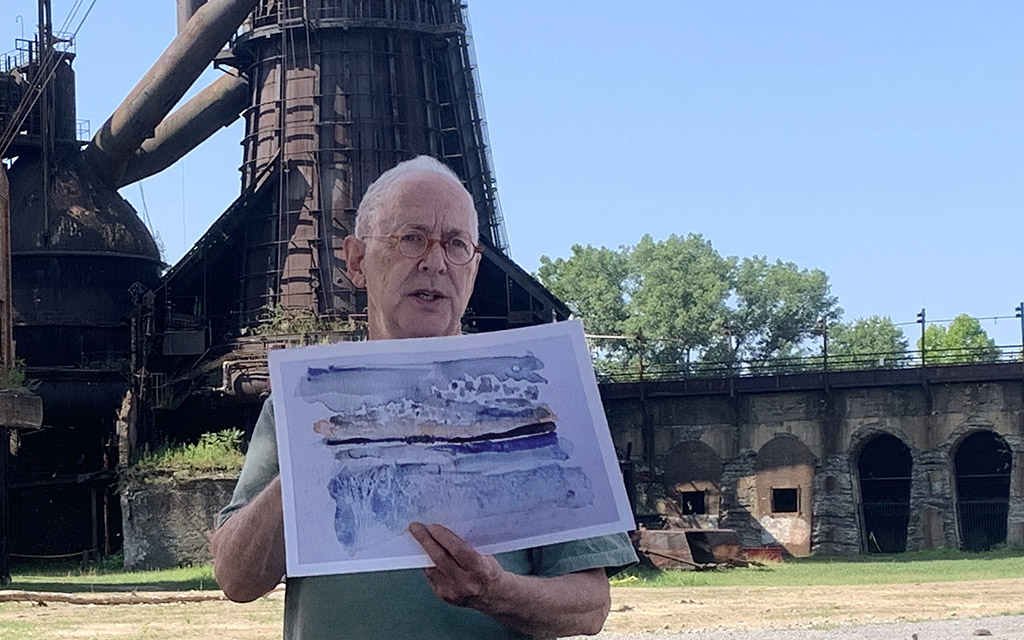

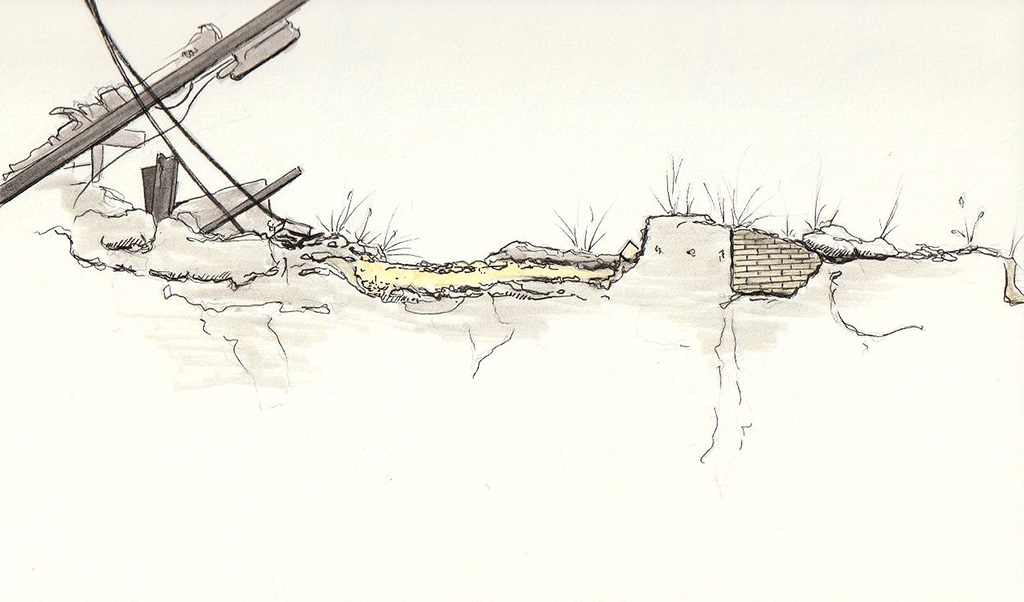

The Iron Garden, as it’s now known, is an area along the eastern border of the landmark site. During the active years of the mill, it housed a structure and additional ore yard. During the intervening decades, after the building was demolished and before Rivers of Steel began managing the site, this area began to be reclaimed by nature, and seeds sprouted from the holes that remained from the removed foundation. Rivers of Steel’s approach was to apply a light touch in cultivating the site and to provide interpretation of the space. The project grew through a partnership with landscape ethicist Rick Darke and the Penn State Master Gardeners. (Read Growing the Iron Garden for the full origin story.)

Then, ten years ago, this creative collaboration of gentle gardening expanded with the addition of gardener Addy Smith-Reiman and her sculptor-husband Josh Reiman to the project. The two artists shared Rivers of Steel’s desire to honor the resiliency of nature as it reclaimed the land in a postindustrial habitat.

Addy Smith-Reiman, with her background in landscape architecture, has been engaging in creative projects celebrating local identities and shared histories for more than 20 years. Josh Reiman’s work has been exhibited worldwide; he’s known for sculpture, film, video, and photography.

Collaborating with Rivers of Steel and Penn State Master Gardeners, Smith-Reiman and Reiman designed and cast iron podiums to be placed along the walking trail through the garden space. Each iron installation revealed a raised drawing of some variety of plant or animal life that resides in the shadow of Carrie Blast Furnaces. As the first items cast on-site since the closing of the furnace in 1982, they represent a significant first step in bringing iron casting back to Carrie.

Visitors to the 2023 Festival of Combustion read from the cast iron interpretive podium created in 2014.

Addy Smith-Reiman reflected, “Carrie is an inspiration for many: artists, historians, and even gardeners. Ten years ago, it was fertile ground (pun intended) for a Master Gardener class to learn about ruderal vegetation and the urban wilds that consumed the landscape. Working from Rick Darke’s initial survey of the site, ten volunteers surveyed over months the ephemeral and opportunistic plants around the Carrie Furnace grounds. To have this data materialize in the plaques, utilizing the historic material of site (iron), and catalyzing the metal arts program to produce the work, the project aptly materialized as The Iron Garden.”

“It is exciting to return, ten years later, to see how the vegetation has changed and how the shift in programming allows plants to now share space with the growing sculpture garden,” she continued.

To mark the anniversary, the Master Gardeners will be stationed throughout the Iron Garden during the festival to help interpret the space, while Smith-Reiman and Reiman will help lead the iron-casting workshop offered by Rivers of Steel in the week leading up to the Festival of Combustion and will participate in the big pour the day of.

Insider Tip: Self-guided tours are available throughout the earlier part of the day, so plan your tour time around other timed activities that you are looking to do.

Tours of the Carrie Blast Furnaces

In addition to the self-guided tours of the Iron Garden, this year Rivers of Steel is also offering self-guided Industrial Tours. This self-paced tour route through the landmark site will include tour guides stationed at various locations, allowing guests to engage with them along the way. As guided tours have always quickly sold out in the past, this new format will accommodate as many event-goers as are interested, in addition to giving them more flexibility in how they spend their day. Additionally, an Ask a Tour Guide information tent will be located near the hub of the activities.

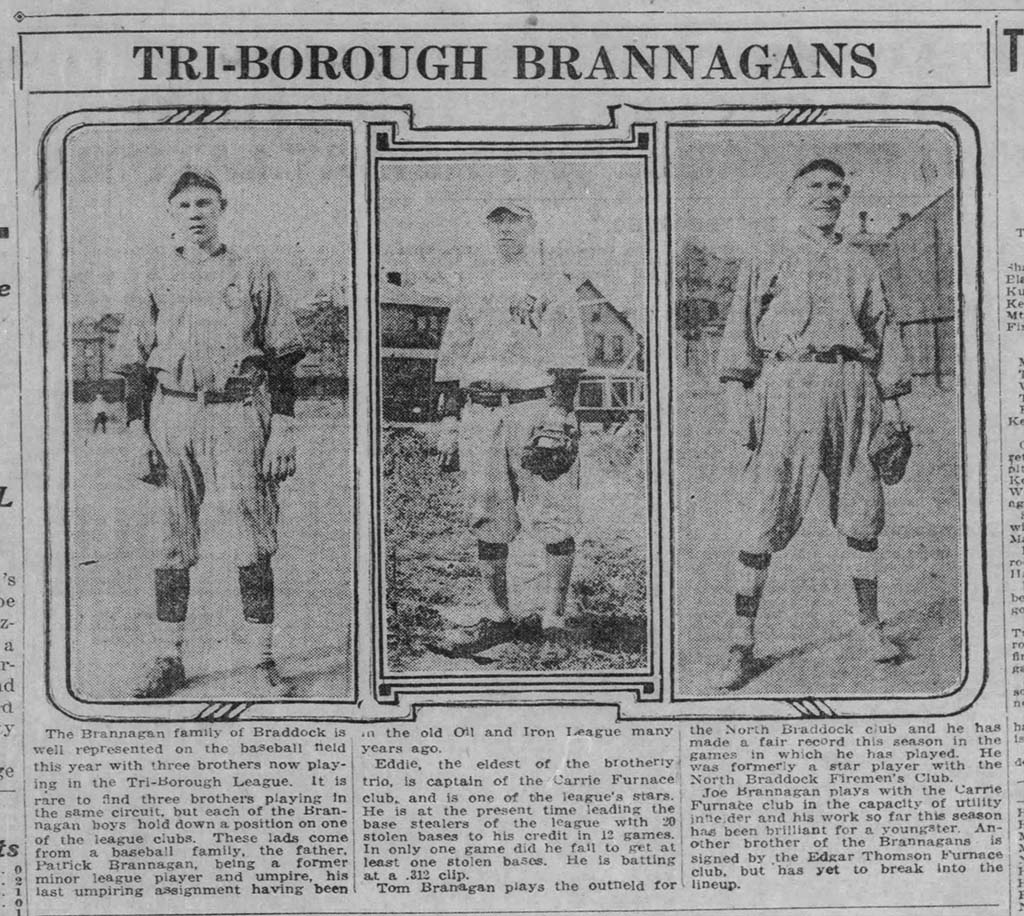

A crew with the Center for Metal Arts in Johnstown work together using a large power hammer.

Industrial Arts Demonstrations

Beyond the iron pour and tours, the demonstrations are always a crowd favorite at the Festival of Combustion. This year new participants include the Center for Metal Arts and artist Talon Smith.

The Center for Metal Arts is an educational program housed at the historic Cambria Iron & Steel forge shop in Johnstown, Pennsylvania. Their mission is to renovate and refurbish historic power hammers and tooling to make them available to be seen by the greater forging community and used by qualified professional blacksmiths—and they will bring a power hammer to the festival! Although it won’t be as large as the one in the photo above, it will certainly make an impression.

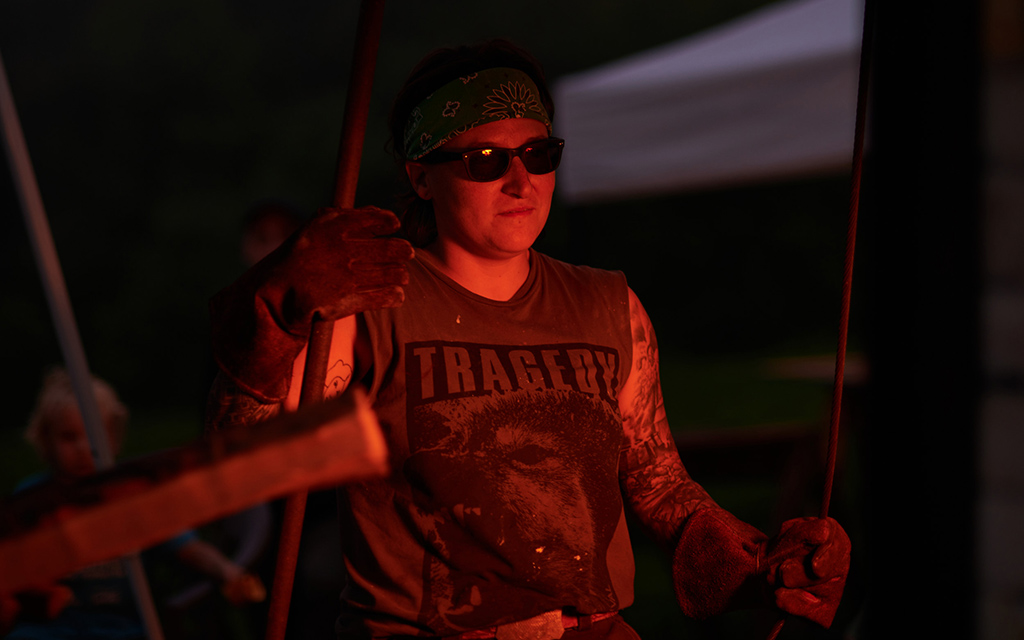

This year will bring a bonus demonstration—by twilight, ceramic artist Talon Smith will partake in a performative wood firing. The performance centers around a small wood kiln. Attendees of the event are invited to engage with the artist and their crew to ask questions about the process as it takes place and witness its glowing result revealed at dusk.

Smith—who identifies as a native Yinzer, has a studio in Polish Hill and a wood kiln in Ligonier, Pennsylvania—describes this wood firing as a performance that celebrates the narratives of our environments and how they change over time. In the context of Carrie, the landscape where the former iron mill is situated has witnessed extreme changes. Over eons, the slow erosion of the Allegheny Plateau created the Mon Valley. The molten years stretched for nearly a century, and the now-silent sentinel hovers as a reminder of generations of workers.

The artist Talon Smith is illuminated from the glow of their kiln.

“Wood firing is a process that demonstrates the combined efforts of individuals working towards a common goal,” Smith said. “Throughout the duration of the Festival of Combustion, a small wood kiln containing one sculpture will be fired and brought to temperature. At peak temperature—around 2,000 degrees Fahrenheit—the petals of the kiln will be opened to reveal a glowing sculpture of an arch. The arch mimics the landscape; it is a monolith left behind representing the narratives of our environments.”

Beyond the symbolism, the warm glow of the revealed sculpture will light up for the crowd just prior to the annual fireworks show.

In addition to the new demonstrations, perennial favorites will return, including glassblowing with The Pittsburgh Glass Center, welding with Patrick Camut Fabrication, and numerous blacksmiths working alongside Rivers of Steel staff.

Insider Tip: Don’t let the hands-on activities be just for the kids. Carve a scratch mold or make your own penny pendant!

American Crafts

If you desire to create your own crafts, wind your way through an assortment of hands-on activities. Mosaics with The Ruins Project, jewelry making with Pittsburgh Center for Arts & Media, raku-fired ceramics with Ton Pottery, STEAM crafts with Assemble PGH, Guild on the Go with Manchester Craftsmen’s Guild, and a Punk Rock Corner all vie for creative exploration.

“The Punk Rock Corner is a collaboration between LIGHT Educational Initiative and Rivers of Steel’s Graffiti Arts program,” said Chris McGinnis. “We’re excited to offer hands-on activities, including graffiti art, patches, zines, and pin making.”

Now in its third year, the Heritage Craft Tent, presented by West Overton Village, is a festival within the festival that explores American heritage traditions, including the tastiest of all heritage crafts: rye whiskey distilling!

“West Overton is excited to participate in the Festival of Combustion for a third year,” said Aaron Hollis, co-executive director of West Overton Village. “As the 2024 sponsoring partner for the Heritage Craft Tent, we look forward to offering engaging opportunities for visitors young and old.”

Insider Tip: For those who imbibe, make sure to try a sample of West Overton’s Monongahela Rye.

The historical organization’s educational distillery revived the tradition of making whiskey at West Overton Village for the first time since Prohibition. Their varieties of rye whiskeys, including a Monongahela Rye, will be available to adults for tastings. Adults can also learn about their new whiskey heritage center, while the younger set is engaged with interactive activities.

“We are grateful for another opportunity to continue our partnership with Rivers of Steel,” Hollis continued.

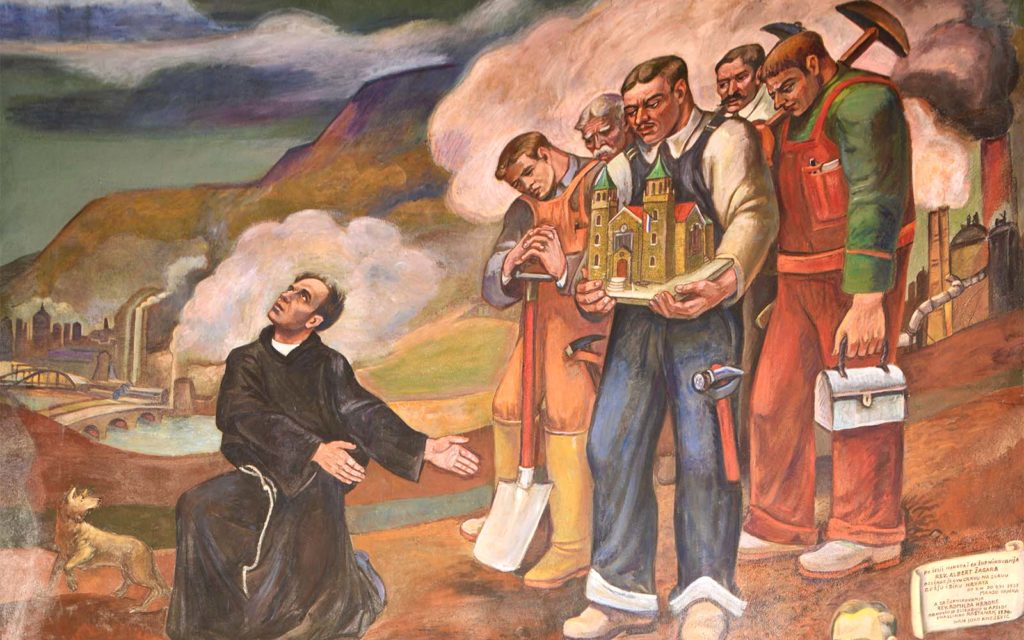

Other hands-on happenings under the Heritage Craft Tent include activities by Rivers of Steel’s other heritage partners: Touchstone Center for Crafts, the Bradford House Historical Association, the Pennsylvania Trolley Museum, and the Society for the Preservation of the Millvale Murals of Maxo Vanka.

Insider Tip: Get a head start on holiday shopping by supporting local makers.

Crafts are not limited to the hands-on variety at the Festival of Combustion; more than a dozen regional artisans are offering their creations in the makers’ marketplace. From ciders and sundries to upcycled car parts and art prints, there is a variety of wares to peruse!

Insider Tip: Check the event schedule if there is a specific performance that you don’t want to miss.

Live Music and Performances

And what would a festival be without entertainment? Beyond the metal pours, demonstrations, crafts, and shopping, there is even more to see.

On the music stage, Ames Harding and the Mirage, Tom Breiding and Union Railroad, and The Polkamaniacs will keep festival-goers entertained, in between sets by DJ Zombo.

A chronicler of small-town America, locally based Breiding said, “Union Railroad will play a set of music that pays homage to our region’s great industrial heritage. Rivers of Steel is such an important link to that heritage, and this festival is my favorite celebration of the year in Pittsburgh.” Breiding’s music lyrically lends understanding to the worlds of coalfields, mines, and mills.

Pop-up performances by Lovely Lady Lydia Artistry offer fire, flame, and other circus arts throughout the evening.

Insider Tip: The fireworks begin at 8:30 p.m. and end by 9:00 p.m.

Food, Finale, and More

If all of this has worked up an appetite, food trucks will tickle a variety of tastes. Farmer x Baker, Pita My Shawarma, Rogue BBQ, Street Fries 4ever, Tango Food Truck, and Taqueria El Pastorcito will be on-site. Craft beer, sponsored by Oskar Blues and Vecenies Distributing, and cocktails will be on hand to add a dash of flavor to this incredible ambiance. Plus, sales of beverages directly support Rivers of Steel and its programmatic and historical preservation efforts at the Carrie Blast Furnaces.

For the adventurous in the crowd, Xpogo will provide instruction and free-to-use pogo sticks for all skill levels and ages, and KSD Studios is offering affordable tattoos.

A day celebrating the innovation and artistry of our region can be capped only by the colorful combustion of a dazzling fireworks display. The fireworks finale takes place from 8:30 to 9:00 p.m., offering an epic end to a memorable day.

Presented By

The Festival of Combustion is simply an experience like no other, making it a spectacular autumn adventure. Plus, with an all-inclusive admission price of $20 for adults and no cost for kids under age 18, it is supremely affordable and family friendly. This is made possible by the financial and in-kind support from our sponsors.

“Rivers of Steel is grateful to our presenting sponsor, U.S. Steel, for their unwavering support of the Festival of Combustion and our broader community initiatives,” said Rivers of Steel’s CEO Augie Carlino. “Their investment plays a key role in preserving Pittsburgh’s rich history as the steel center of the world, ensuring that the story of our industrial legacy continues to inspire and educate. Together, we are celebrating the industrial heritage that forged Pittsburgh and southwestern Pennsylvania and helped shape the nation.”

Rivers of Steel is also grateful for the support of West Overton Village, sponsors of the Heritage Craft Tent, for their underwriting contributions for this event.

Rivers of Steel is thankful for NEXTpittsburgh, who is the exclusive media sponsor for the 2024 Festival of Combustion; Jackson Welding Supply Co., Inc.; Oscar Blues; and Vecenies Distributing—all of whom are additional fiscal sponsors, and TMS International who provides in-kind support.

Beyond these partners, Rivers of Steel recognizes the event would not be all that it is without the support of our programmatic collaborators.

“The Festival of Combustion has grown so much over the years, and we are particularly excited to welcome more than 50 collaborators in 2024,” said Chris McGinnis. “So much of what makes this event special comes from the many friends and partners who bring their unique and creative work to Carrie Blast Furnaces each year!”

That said, the magic of the day is contributed by the thousands of folks from southwestern Pennsylvania and beyond who join us to marvel in the fiery spectacles and immense talent of our region’s artists, makers, and builders. They truly make this a celebration of industrial arts and American crafts!

Insider Tip: Guests 21+ who are seeking to imbibe, should stop at the I.D. Check to get a bracelet before getting in line to purchase beverages.

Tickets and Information

The Festival of Combustion is hosted by Rivers of Steel at the Carrie Blast Furnaces National Historic Landmark, located at 801 Carrie Furnace Blvd., Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, 15218.

The event is from 1:00 to 9:00 p.m. on Saturday, October 5, 2024. Some hands-on activities and demonstrations conclude at 6:00 p.m., as activities shift from the Central Courtyard to the Western Courtyard and more performances begin. This year, no reservations are needed for tours, but folks looking to carve a scratch mold should participate earlier in the day, as supplies may run out. All tours and activities are included in the ticket price.

Food is available for purchase, and visitors may want to budget for marketplace discoveries. Also, those looking to purchase adult beverages will need to stop at the I.D. Check to receive a bracelet before going to the beer and cocktails tent. Festival of Combustion T-shirts and other commemorative merchandise are available from Rivers of Steel at the gift shop near the entrance gates.

General admission tickets can be purchased here for $20 in advance for adults. Kids are free; however, tickets must be reserved. Free parking is available on-site, with additional spaces reserved for those with limited mobility.

About Rivers of Steel

About Rivers of Steel

Founded on the principles of heritage development, community partnership, and a reverence for the region’s natural and shared resources, Rivers of Steel strengthens the economic and cultural fabric of western Pennsylvania by fostering dynamic initiatives and transformative experiences.

Rivers of Steel showcases the artistry and innovation of our region’s industrial and cultural heritage by offering unique experiences via tours, workshops, exhibitions, festivals, and more. Rivers of Steel supports economic revitalization throughout the eight counties of the Rivers of Steel National Heritage Area by working to deepen community partnerships, promote heritage tourism, and preserve local recreational and cultural resources for future generations.

Jordan Snowden is a freelance writer based in Pittsburgh whose work has been published in The Seattle Times, Pittsburgh City Paper ,and elsewhere. She also runs @jord_reads_books, a book-focused Instagram account where she connects with other bookworms. In her free time, Jordan can be found with a book in her hand or DIYing something with her husband.

Jordan Snowden is a freelance writer based in Pittsburgh whose work has been published in The Seattle Times, Pittsburgh City Paper ,and elsewhere. She also runs @jord_reads_books, a book-focused Instagram account where she connects with other bookworms. In her free time, Jordan can be found with a book in her hand or DIYing something with her husband.

About Rivers of Steel

About Rivers of Steel Julie Silverman is a museum educator, tour facilitator, and storyteller of astronomy and history for various Pittsburgh-area organizations, including Rivers of Steel. A Chatham University 2020 MFA graduate, her writing is most often found under the byline of JL Silverman. Occasionally, under the name of Julia, she has been seen on TV.

Julie Silverman is a museum educator, tour facilitator, and storyteller of astronomy and history for various Pittsburgh-area organizations, including Rivers of Steel. A Chatham University 2020 MFA graduate, her writing is most often found under the byline of JL Silverman. Occasionally, under the name of Julia, she has been seen on TV.

Barney Terrell is a tour guide, historian, and researcher for Rivers of Steel and is a tour facilitator at The Frick Pittsburgh. He is a member of the Society for American Baseball Research, a true crime author, and a trivia host.

Barney Terrell is a tour guide, historian, and researcher for Rivers of Steel and is a tour facilitator at The Frick Pittsburgh. He is a member of the Society for American Baseball Research, a true crime author, and a trivia host.

CM: When you consider this exhibition, how are individual workers represented as compared to the collective “worker”?

CM: When you consider this exhibition, how are individual workers represented as compared to the collective “worker”? CM: Tell us more about the Jack Boot series.

CM: Tell us more about the Jack Boot series.