Community Spotlight—Hazelwood’s Community Artworks

Public art, by definition, is intended to be for the people. However, even when it is considered site-specific, it is often not of the people. That is not the case in Hazelwood, though. Over the last several years, newly-created public artworks have been shaped by the views of Hazelwood’s own residents. Now, on the eve of a new sculpture’s installation, Julie Silverman takes a look at the constellation of community stakeholders who are working together to beautify their neighborhood.

By Julie Silverman, Contributing Writer

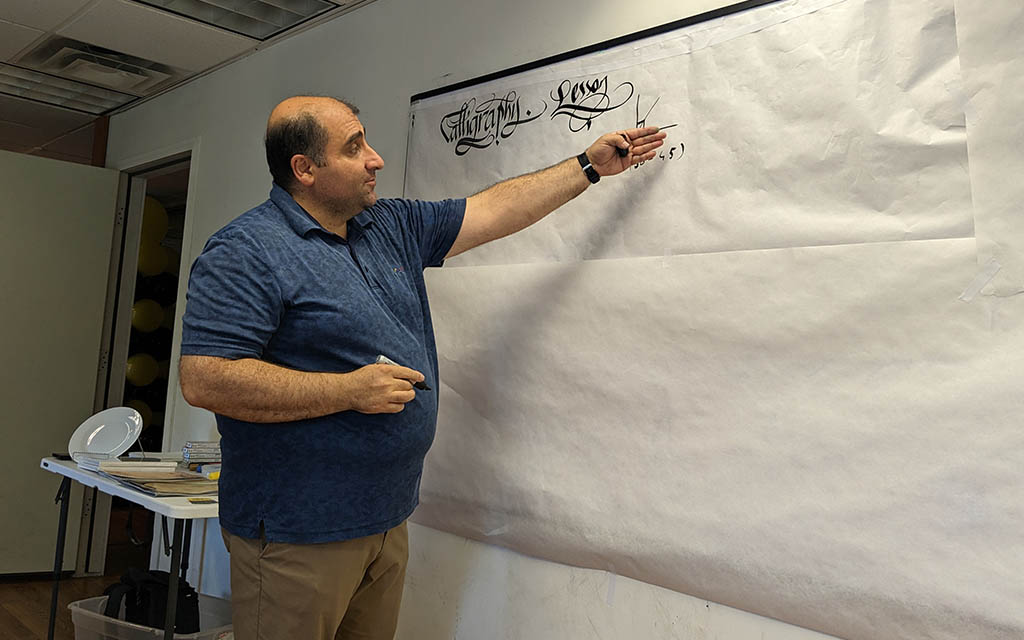

Artist Ben Grubb stands with his in-progress sculpture that is currently being installed in Hazelwood. Photo by Hank Malone.

Crossing Beacon, Illumin-Ave, and Hazelwood Alive

Old and new have a tradition of residing side by side in Pittsburgh. Alexander Jozsa Bodnar was the owner and chef of the beloved restaurant that anchored the corner of Hazelwood and Second Avenue. The ordinary building housed an extraordinary cross-section of guests at the restaurant, from Hazelwood neighbors to the late Anthony Bourdain.

An upcoming public art piece at 4800 Second Avenue, the former home of Jozsa Corner, will encapsulate old and new in its design as a cross section of art, architecture, and history, and will wrap the second and third floors of the building with a sculptural art installation called Crossing Beacon. Artwork sponsor Hazelwood Local and project partner Hazelwood Initiative are hosting an event on December 9 in celebration of the community-driven art project.

With broad community support and organizational collaboration, art has thrived in the community of Hazelwood. And for this latest project, a call for artists was released, encouraging Hazelwood artists or artists with ties to the community to bring their ideas for consideration. Community members were invited to meet the group of artists selected to produce design proposals for the artwork and brainstorm community-centric themes or motifs to be represented in their work. The integration of community engagement led to the selection of artisan sculptor and steel fabricator Ben Grubb.

“Crossing Beacon is an amalgamation of what we see now, our capacity to imagine the past, and our ability to let that inform our future,” said artist Ben Grubb. “The city, this building, the land where you are now standing, were once under water. As we imagine that time before us, may we also reach forward with our minds and our hands towards a healthful relationship with one another and the life that surrounds us, knowing we have been here but a moment’s time.”

Dana Wall, director of Hazelwood Local, a creative, community programming initiative, said of Ben’s design, “Ben’s motifs give a thoughtful nod to the river, the steel industry, and the community. The building was chosen because it is uniquely situated at the location of the once entrance to the Jones and Laughlin Steel mill and was a part of a formerly bustling neighborhood block—a corner that is a welcome transition into the neighborhood of Hazelwood.”

Originally a Native American territory, the area of Hazelwood was settled by Scottish immigrants in the 1780s and less than a century later grew with industry and glowed with the production of steel from the Jones and Laughlin Steel Company. At peak production, the neighborhood population reached thirteen thousand residents. Second Avenue was a robust commercial corridor of restaurants, bars, grocery stores, retail stores, and a movie theatre. As the steel industry declined and operations slowed, eventually closing in 1997, the resident population decreased to the approximately five thousand current residents living in Hazelwood today.

A group of Hazelwood residents visit the studio of artist Ben Grubb with Arts Excursions Unlimited. L to R: Nita, Denise, Aceton, Ben, Nyron, Harry, Maleaka. Cassandra, Ocean, and Keyvion. Photo by Edith Abeyta.

Edith Abeyta is an artist who works with the Hazelwood residents through Arts Excursions Unlimited. In addition to collaborating with other community organizations on the development of art projects and providing arts excursions for local youth, she facilitates conversations about creative initiatives with Hazelwood community members. She looks at Crossing Beacon as merging of many topics within the neighborhood. “It combines the notion of pre-settler colonial time frames, referencing the river, referencing the mayfly, but using steel and some of the shapes that I see in the neighborhood and definitely the colors, like the green color that references the steel industry, the same color as the uniforms that people would wear in the mills.”

Crossing Beacon is the third public art project implemented by Hazelwood Local that brought together neighborhood residents and artists. In 2021, five art installations were placed in the interior of storefronts along the Second Avenue corridor. Dubbed Illumin-Ave, these installations illuminated everyday businesses and spaces with brightly lit original artists’ works. The following year, Hazelwood Alive arrived at the intersection of Lytle and Eliza streets. Situated near Hazelwood Green Plaza, an artistically designed shipping container welcomed passersby with a joyfully painted display of native flora and the words “Hazelwood Alive”—a phrase credited to Hazelwood neighborhood historian JaQuay Edward Carter.

The Hazelwood Alive installation. Photo by Hank Malone.

Now, in 2023, Hazelwood nights will once again light up with Grubb’s installation at The 4800 Gateway. The creative design of Crossing Beacon will shine with solar-powered lights, illuminating facets of the art from in front and casting light through other panels from behind. The lighting will be mounted to the work, and the entire sculptural piece will be carefully affixed to the building to maintain the integrity of the architecture. It is anticipated that the artwork will remain in this location for one year. After that, aspects of the artwork are designed to later become part of the community. Large panels can be converted to raised vegetable-bed planters that could contribute food to the community.

Team members with the Industrial Arts Workshop are installing welded metal braids to complete the Braids of Hope artwork. Photo by Heather Mull Photography.

Braids of Hope

Recently, Abeyta was one of several collaborators in Hazelwood that supported the creation of the Braids of Hope multimedia art installation that appears at the corner of Tecumseh and Second Avenue and was dedicated on October 13, 2023. The project, which was a partnership between Arts Excursions Unlimited, Hazelwood Initiative, Industrial Arts Workshop (IAW), and Elevationz, a local building that is home to four small business, resulted in a vibrant collaboration engaging community input and student welders, whose collective design melded a painted mural and the tactile power of braided metal.

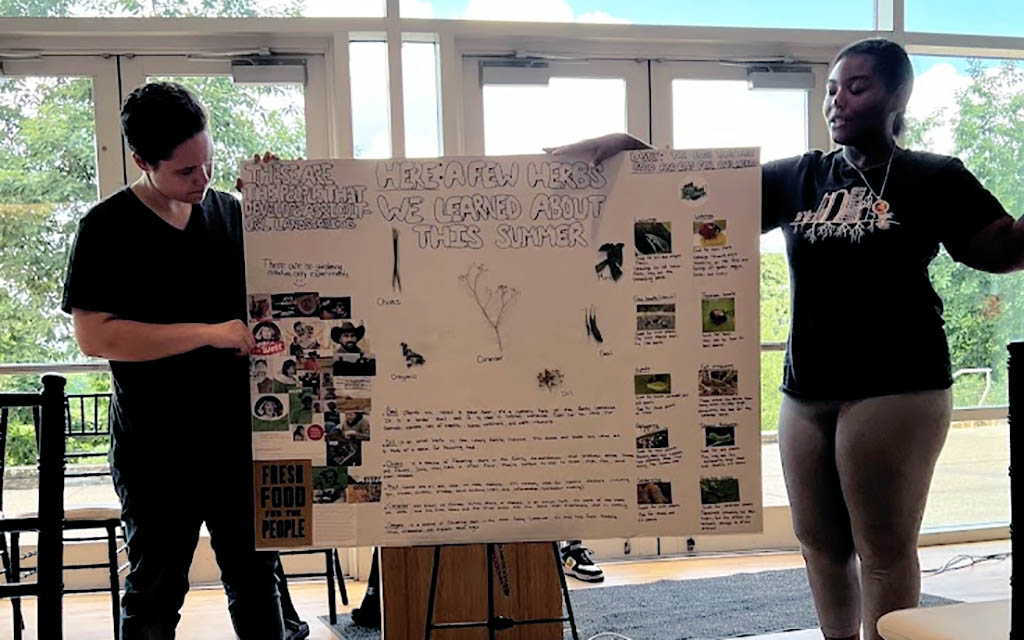

“Braids of Hope came directly out of community ideas,” said Maura Bainbridge, assistant director with the Industrial Arts Workshop. “Edith Abeyta, of Arts Excursions Unlimited, conducted a series of meetings with Hazelwood residents over a few months about their ideas for public artwork at the site. She compiled these ideas into word clouds about artwork themes and data around preferred colors and art styles that we then shared with our Summer Welding Bootcamp students.”

“IAW’s Summer Welding Bootcamp students, ages 16–18, were tasked with interpreting this community feedback and developing ideas for the piece. They worked individually and in groups to refine their ideas, present them to each other, and ultimately to combine them into one cohesive piece,” Bainbridge continued. “Visiting artists and Hazelwood community members also provided feedback at various points during the summer. Summer Welding Bootcamp students were not only empowered by learning to weld and exploring their future possibilities, but they also understood their work in the context of the neighborhood. They considered how people might feel seeing Braids of Hope every day and how their piece fit into community visions. It was clear to me that our students were proud of this impact and took it seriously. The feedback that we’ve heard from Hazelwood neighbors since completing Braids of Hope also reflects this, as folks seem to feel that our students created something meaningful on that corner, and that feels like success to us!”

Abeyta had help with the Rocking Cradle project from two high school students enrolled in the Start on Success program. Photo by Lake Lewis.

Rocking Cradle

Nearby, a walk through Hazelwood Green, the former steel mill site, will find you among multiple pieces of art. Under the artistic guidance of Abeyta and led by professor Dana Cupkova of Carnegie Mellon University’s School of Architecture, the team partnered with Center of Life, a local nonprofit in Hazelwood that provides afterschool and summer programs to students, families, and community members in the areas of education, the arts, family strengthening, athletics, enrichment, and social justice. Collectively, they produced the Rocking Cradle—Urban Furniture for Environmental Justice project.

Seats in a cradle-rocker shape were created through 3-D printing. The seats can be used to perch or as planters for native species plants. Their dark winged shapes dot the surrounding green. Students participated in workshops that were held through Center of Life’s Fusion afterschool program. The team generated text to embed on the rockers, having sought inspiration from written text found throughout the neighborhood. The result is a combination of art, ecology, and the voices of Hazelwood.

“Hazelwood built a large portion of Pittsburgh utilizing the former steel mill on the Hazelwood Green site,” said Center of Life’s Patrick Ohrman. “Visiting the site to see this installation and all of the new development is an opportunity for people to really understand the history of Hazelwood. This project is a testament to the power that can be created when nonprofit organizations and universities work together to transform the ways in which others think about development.”

Hazelwood resident Heather Mull appreciates the entrance to the Hazelwood Community Garden. Photo by Heather Mull Photography.

Community Voices

Abeyta has questioned “Whose vision moves forward?”—a notion echoed by neighbors who feel parts of their community are being redeveloped without their input. For Abeyta, it is a question that relates to collaborative art projects and environmental issues. It is one that encompasses art embedding itself in a community and finding durability with a community’s resilience. Murals thrive in Hazelwood along the Second Avenue corridor and on the Elizabeth Street Bridge with design and fabrication done in collaboration with Hazelwood residents.

The Elizabeth Street Bridge mural. Photo by Heather Mull Photography.

Photographer Heather Mull is one of those residents, having moved to the neighborhood in 2005 and been witness to the slow march of redevelopment in the nearly two decades since.

“Public art can be an early bellwether for transformation in a neighborhood, especially one that contains buildings in need of renovation like ours,” stated Mull. “I think that’s why it is often viewed as “controversial,” because response to art is so subjective and personal. There is always an inherent tension brought up by conspicuous change within communal spaces.”

Carin Mincemoyer’s design for the tree grates at Hazelwood Green. Photo by Heather Mull Photography.

“For me, the best pieces make me notice, all of a sudden, some feature of a building or a street that I’d never really thought about before,” Mull continued. “Like how the brightly painted steps and fence decorations on the entrance to Hazelwood’s community garden at the former YMCA building (at the top of Minden Street) took some really plain and unattractive infrastructure and made it look cheerful and welcoming. Similarly, Carin Mincemoyer embedded the shapes of the hazelnut tree’s leaves and seeds into the metal planting grates around the new sidewalk trees at Hazelwood Green. But not all public art needs to be cheerful, either. I love the caring way Marce Nixon-Washington’s painted her friend Tonee Turner, who has been missing since 2019, onto that dingy, boarded-up window along Second Avenue. The message of that piece is so important and deserving of attention.”

The Tonee Turner installation. Photo by Heather Mull Photography.

“Hazelwood residents that I know do really like art and like to see art in their neighborhood,” Abeyta reflected. “It also operates on a timeline that they’re involved in.” Residents are part of the decision-making in the beginning. The art has been selected and informed by community members. They see it through the process in the middle.” And by the end, Abeyta states, “It didn’t take ten years or five years to make it happen. It’s more immediate. It’s one of the powerful things about it. It’s the arts’ ability to connect people.”

Community Opportunities

People in Hazelwood will have had the opportunity to walk by and see the new Crossing Beacon installation as it is being built the week of November 27th. Being lit at night, it will continue to catch people’s eye, or they can watch the progress on Hazelwood Local’s Instagram. Ben’s design “is pretty formal,” Abeyta says. “It has a lot of conceptual ideas behind it. It’s not illustrative. I’m curious to see how people respond to it.”

Join Hazelwood Local and Hazelwood Initiative on December 9 to see the completed Crossing Beacon for yourself and enjoy a celebration of past and present filled with stories of how the artwork came to be, family-friendly craft activities, and refreshments.

About The Community Spotlight Series

The Community Spotlight series features the efforts of Rivers of Steel’s partner organizations, along with collaborative partnerships, that reflect the diversity and vibrancy of the communities within the Rivers of Steel National Heritage Area.

Julie Silverman is a museum educator, tour facilitator, and storyteller of astronomy and history for various Pittsburgh area organizations, including Rivers of Steel. A Chatham University 2020 MFA graduate, her writing is most often found under the by-line of JL Silverman. Occasionally, under the name of Julia, she has been seen on TV.

If you’d like to read more of our Community Spotlight stories, click here.

Jon Engel is the Heritage Arts Coordinator for Rivers of Steel and the author of the Heritage Highlights column.

Jon Engel is the Heritage Arts Coordinator for Rivers of Steel and the author of the Heritage Highlights column.

Gita Michulka is a Pittsburgh-based marketing and communications consultant with over 15 years of experience promoting our region’s arts, recreation, and nonprofit assets. Read her prior article on 2023

Gita Michulka is a Pittsburgh-based marketing and communications consultant with over 15 years of experience promoting our region’s arts, recreation, and nonprofit assets. Read her prior article on 2023

Gita Michulka is a Pittsburgh-based marketing and communications consultant with over 15 years of experience promoting our region’s arts, recreation, and nonprofit assets.

Gita Michulka is a Pittsburgh-based marketing and communications consultant with over 15 years of experience promoting our region’s arts, recreation, and nonprofit assets.

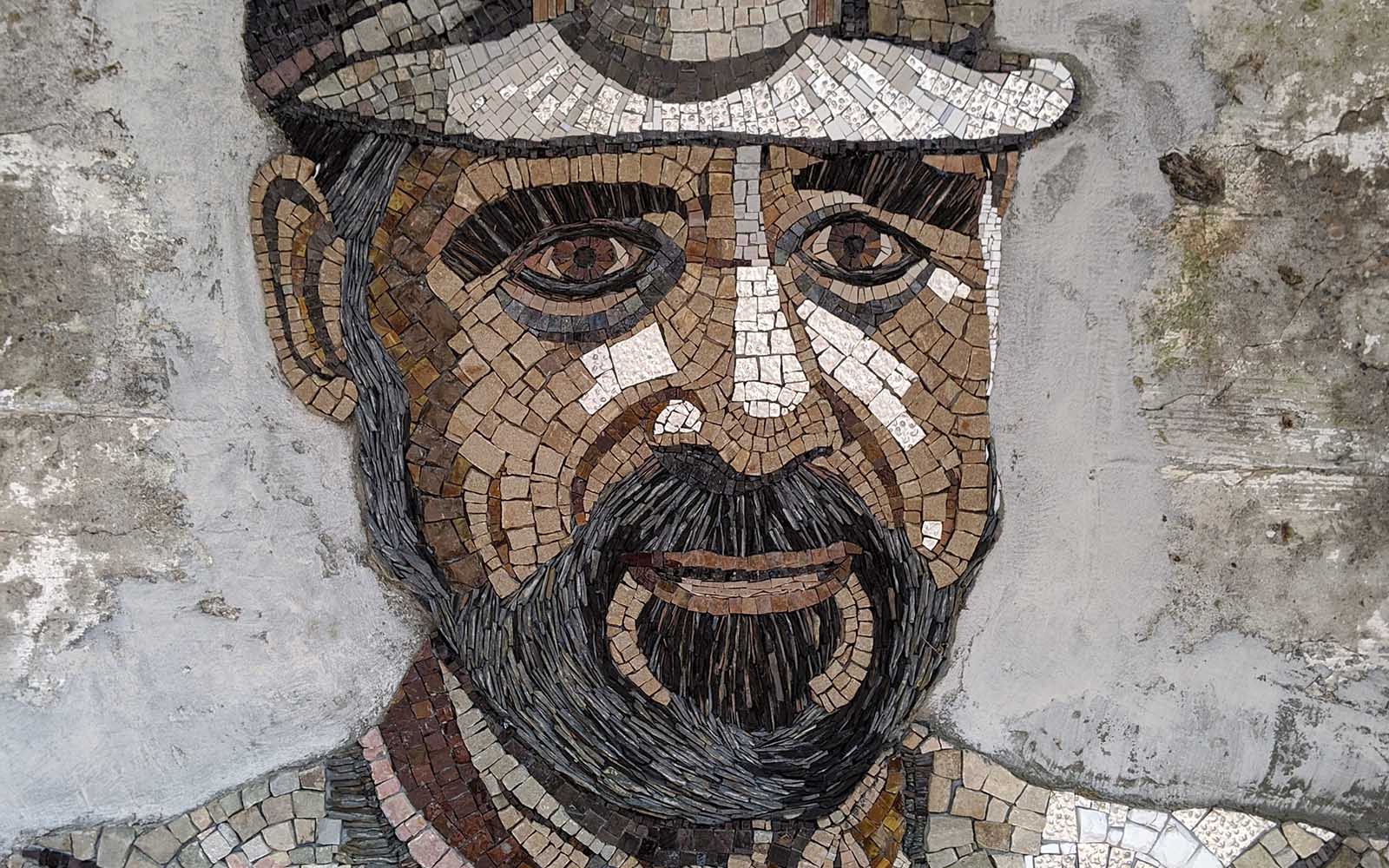

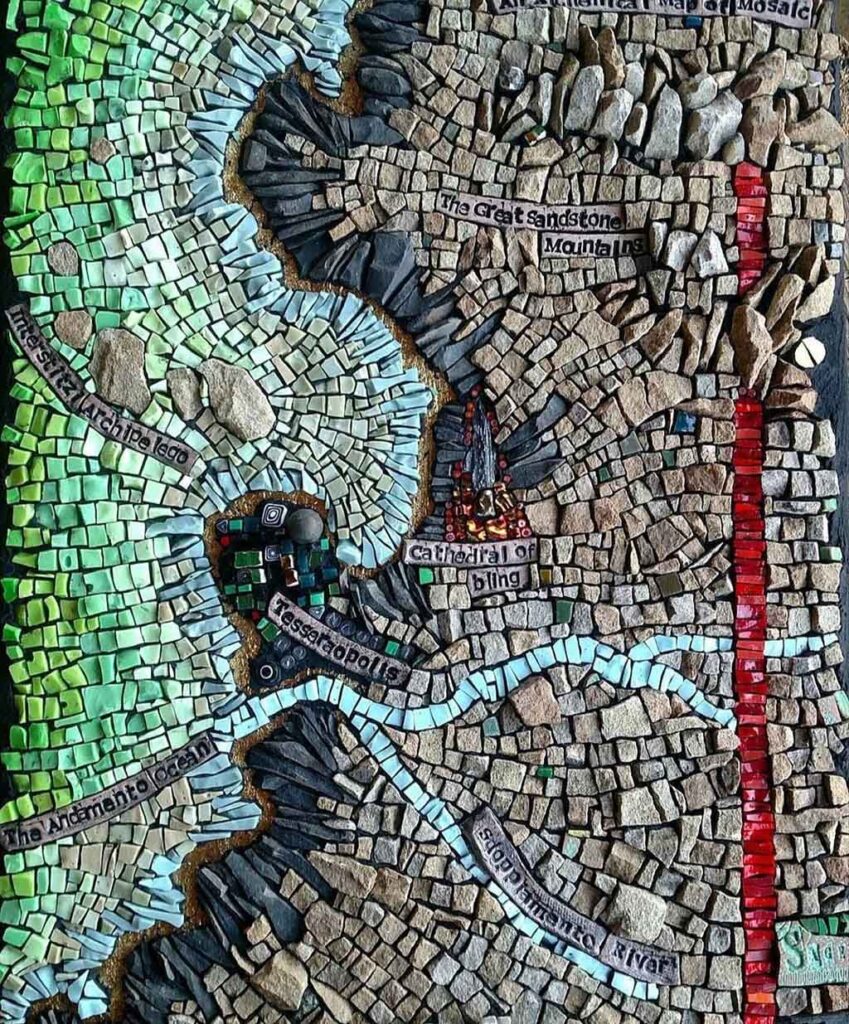

Rachel Sager, The Storytelling Mosaicist, has been making mosaic, writing about mosaic, speaking about mosaic, and teaching mosaic for over twenty years. Her signature forager and intuitive teaching styles have changed how mosaic is experienced and have helped build on the golden age that the art form is enjoying in these exciting decades.

Rachel Sager, The Storytelling Mosaicist, has been making mosaic, writing about mosaic, speaking about mosaic, and teaching mosaic for over twenty years. Her signature forager and intuitive teaching styles have changed how mosaic is experienced and have helped build on the golden age that the art form is enjoying in these exciting decades.