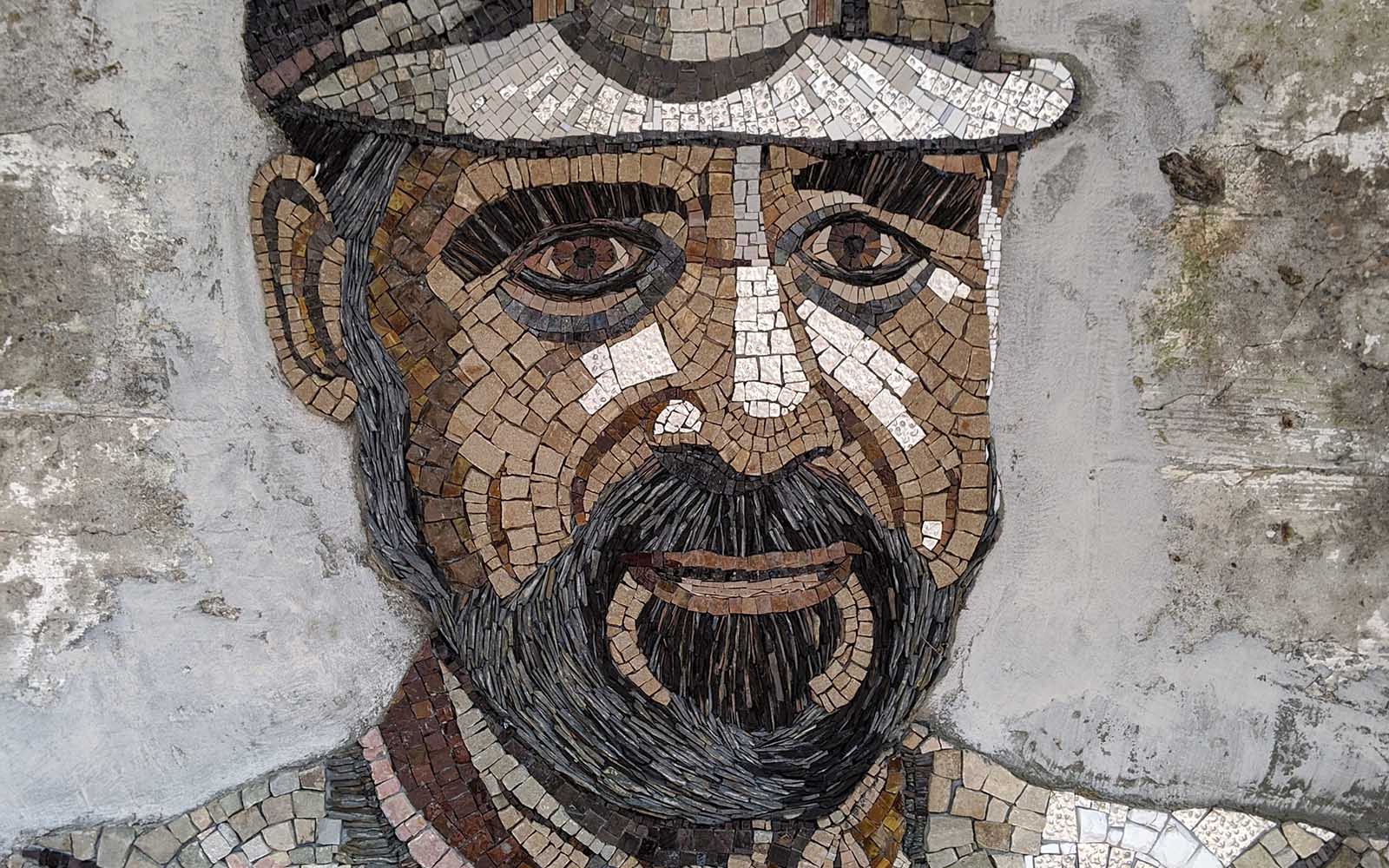

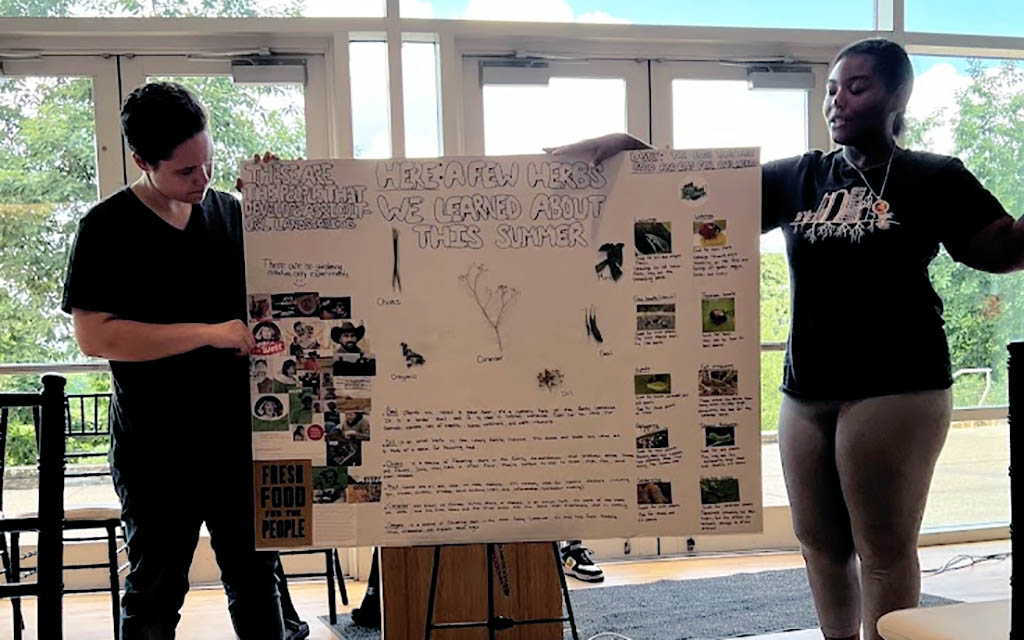

Braddock artist Latika Ann, shown here at the Festival of Combustion, is one of more than seventy community partners that Rivers of Steel worked with in 2023. From site-specific art, like the Mini Greens 2 installation that Latika helped create, to Mini Grant projects, co-programed events, and multiyear community residencies, Rivers of Steel’s joint efforts this year are setting the stage for a dynamic new initiative in 2024 and beyond.

Recent Collaborations with Rivers of Steel . . . And What’s Next

By Carly V. McCoy

When your mission is to support the economic revitalization of an eight-country region, collaboration with community partners is essential—and at Rivers of Steel, it is part of our organization’s DNA.

Formed at a time when southwestern Pennsylvania was suffering from the worst economic and social effects of the collapse of the steel industry, our founders set out to improve the economic opportunities of former mill and coal towns, while also securing the unique cultural heritage of those communities.

These efforts began by establishing connections throughout the region—collecting oral histories, accepting archival donations, assessing the needs of specific towns and boroughs, and finding resources to support economic development, often through heritage tourism and outdoor recreation initiatives.

In the decades since, the ways in which Rivers of Steel supports local communities has only expanded. In 2023 alone, we have worked with more than seventy nonprofits, small businesses, local governments, cultural centers, and individuals on an array of partnerships designed to uplift and engage our neighbors throughout the eight counties of the Rivers of Steel National Heritage Area.

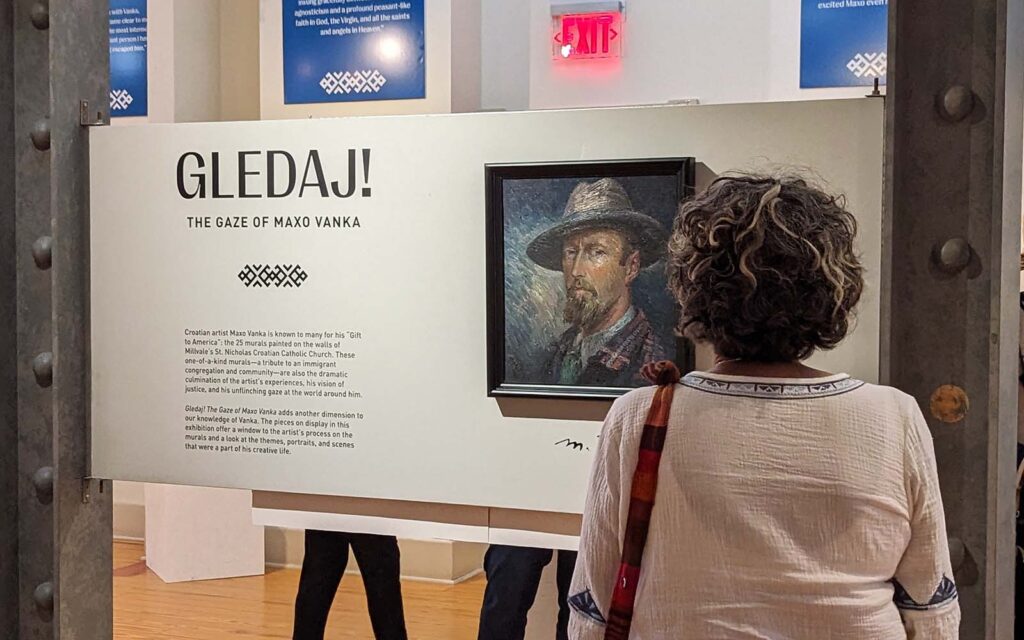

A Mini Grant awarded to the Society for the Preservation of the Millvale Murals of Maxo Vanka help to fund their exhibition Gledaj! The Gaze of Maxo Vanka, which was displayed at the Bost Building in partnership with Rivers of Steel.

The Mini-Grant Program

Rivers of Steel’s Mini-Grant Program is one of our organization’s longest-running economic redevelopment efforts. It assists heritage-related sites and organizations as well as municipalities within the Rivers of Steel National Heritage Area to develop new and innovative programs, partnerships, exhibits, tours, and other initiatives.

Funded projects support heritage tourism, enhance preservation efforts, involve the stewardship of natural resources, encourage outdoor recreation, and include collaborative partnerships. Through these efforts, Rivers of Steel seeks to identify, conserve, promote, and interpret the industrial and cultural heritage that defines southwestern Pennsylvania.

Earlier this year, Rivers of Steel awarded mini grants to seven nonprofits and communities, including ones supporting Grow Pittsburgh, the Fiberarts Guild of Pittsburgh, and the Society to Preserve the Millvale Murals of Maxo Vanka.

In addition to providing project funds, Rivers of Steel supports grant recipients through additional coaching as needed, and by helping to promote their events and share the stories of their accomplishments through our Community Spotlight series.

Rivers of Steel administers the Mini-Grant Program with funding provided by the Community Conservation Partnerships Program and the Environmental Stewardship Fund from the Pennsylvania Department of Conservation and Natural Resources.

The deadline for the next round of grant funding closed earlier this week. However, interested parties can learn more here or sign up to be notified when the next application window opens.

JADED, an artist collective celebrating AAPI art and culture in Pittsburgh, hosted their event Wildness at the Pump House in August.

Historic Preservation and Shared Spaces

Historic preservation has been one of Rivers of Steel’s pathways to regional economic redevelopment through heritage tourism. During the last three decades, Rivers of Steel has stewarded numerous preservation projects, helping organizations and communities determine which of their assets are historically significant.

While not every building needs to be saved, records and objects are often important to understanding our region’s heritage. Sometimes Rivers of Steel becomes the repository for these items, while other times Rivers of Steel is the organization that secures the resources needed to preserve important historical sites for future generations.

The largest of those sites, and arguably the most notable, is the Carrie Blast Furnaces National Historic Landmark. Securing landmark status was only the first step in Carrie’s preservation story, a journey that is ongoing.

Rivaling Carrie for historical significance are two locations that help tell the tale of the 1892 Battle of Homestead and the subsequent Lockout and Strike—the Bost Building in Homestead, which was the headquarters for the Amalgamated Association of Iron and Steel Workers during the conflict, and the Pump House in Munhall, where the actual battle took place.

Today, the Bost Building is the headquarters for Rivers of Steel, as well as the Visitors’ Center for the Rivers of Steel National Heritage Area. It hosts exhibitions in its gallery spaces and is home to Rivers of Steel’s archival collections. The Pump House serves as a trailhead for the Great Allegheny Passage, in addition to hosting public art, picnic facilities, a labyrinth, and a variety of events.

Key to the success of each of these locations is their ability to be used, often creatively, for multiple purposes. This includes leveraging those spaces to help meet the objectives of our community partners.

For the past two years, Rivers of Steel has partnered with the Pittsburgh Irish Festival to host their annual weekend event at the Carrie Blast Furnaces. While supporting our cultural heritage preservation goals and inviting new people to the landmark, it provides the nonprofit with a culturally relevant space that is large enough to host the thousands of visitors they receive each year.

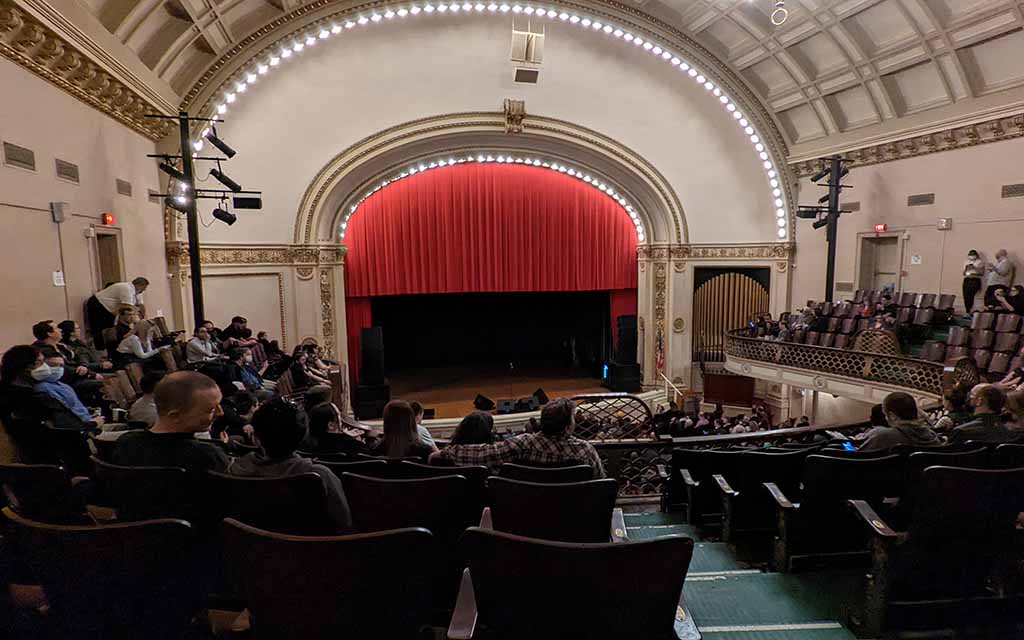

In 2023, Quantum Theatre also returned to Carrie. For this year’s event, they presented Shakespeare’s Hamlet in the Western Courtyard to critical acclaim. The play was a follow-up to their 2019 production of King Lear, which was housed in the Carrie Deer Courtyard and the Green Room of the Iron Garden, two other locations on the Carrie Blast Furnaces site.

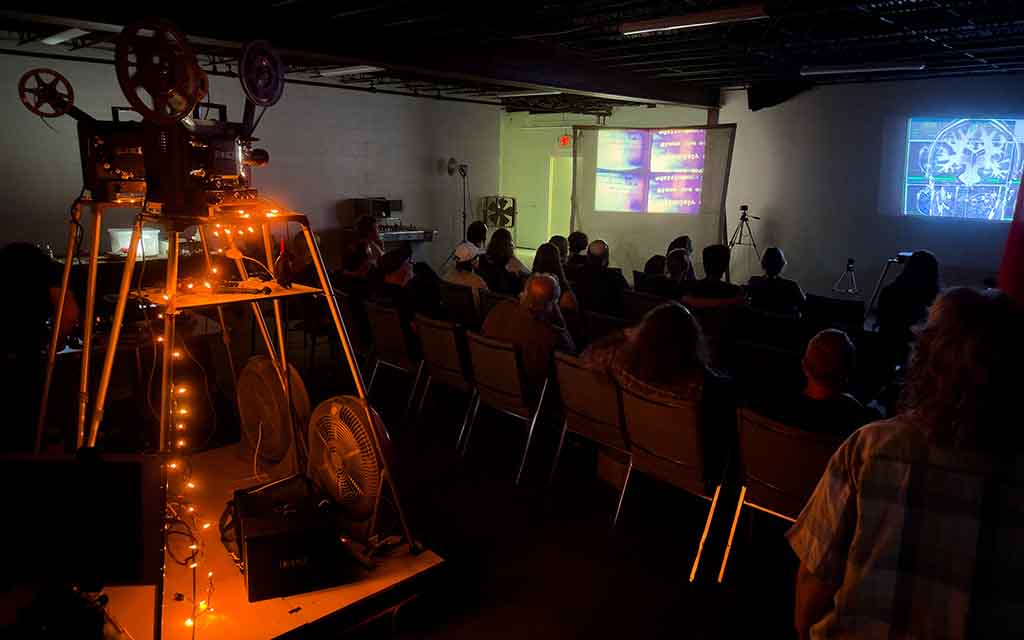

At the Pump House, Rivers of Steel helped support several community happenings by offering use of the space, including to Tree Pittsburgh for a tree adoption event, to the Mon Yough Area Chamber of Commerce for their Tour de Mon cycling event, and to JADED, an artist collective celebrating AAPI art and culture in Pittsburgh, for their Wildness event.

Rivers of Steel also extends a discount to nonprofits who are looking to host their events on the Explorer riverboat, which Three Rivers Waterkeeper did for their Celebrating Clean Water event this past October.

In September, the Carrie Blast Furnaces hosted the world-traveling puppet Little Amal for a performance called Little Amal and the Ghosts of the Furnace, presented in partnership with Real Time Arts.

Collaborative Programming

In addition to sharing spaces, Rivers of Steel also works collaboratively on the programmatic level.

A special highlight of 2023 was the Gledaj! The Gaze of Maxo Vanka exhibition at the Bost Building offered in partnership with the Society to Preserve the Millvale Murals of Maxo Vanka and curated by Steffi Domike. The show expanded the understanding of this unique artist by offering a window to his process and providing context for themes seen across his creative life.

Throughout the year, Rivers of Steel gave community talks at local libraries, including presentations on Carrie Clark at the Mt. Lebanon Public Library and Northland Public Library, and a workshop on Preserving Your History at the Carnegie Library of Homestead.

For their first in-person Be My Neighbor Day last March, WQED brought in Rivers of Steel to help provide family programming at the event at two locations in Homestead.

In May, Rivers of Steel had the opportunity to partner with Green Building Alliance to present a sustainability-focused tour of the Carrie Blast Furnaces, as well as with the Pennsylvania State Education Association for a year-end experiential celebration for local educators.

During the summer, Rivers of Steel Arts partnered with Rankin Christian Center, Propel Braddock Hills High School, Propel Andrews Street High School, and the Art in the Garden program to offer metal arts, graffiti arts, and blacksmithing workshops to area teens.

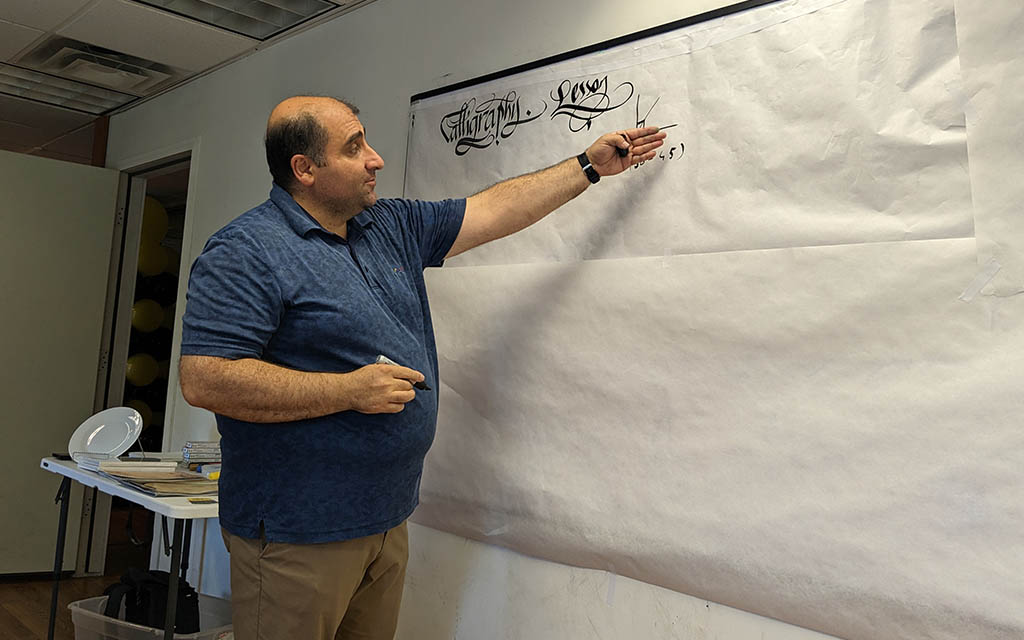

Rivers of Steel also recently concluded a yearlong heritage arts program with the Pittsburgh Center for Arts & Media that brought together three cultural centers, four traditional artists, and three trained teaching artists on a project called Currents. The goal was to help immigrant artists, who are already skilled in a cultural practice, learn techniques to become just as skilled at being a teaching artist. Then each newly trained artist led a workshop at their own cultural center.

On the regional level, Rivers of Steel Heritage Tours launched a new itinerary for the Rebellious Spirits tour that pairs visits to historical attractions—all associated with the Whiskey Rebellion—with tasting experiences at Washington County whiskey distilleries.

Beyond the events mentioned above, Rivers of Steel collaborated with several schools on customized graffiti arts residency programs and with the Heinz History Center for History Day. Additional educational collaborators in 2023 included Remake Learning, the Waterways Association, Commonwealth Charter Academy, Carnegie Mellon University, and Duquesne University, among others.

In 2023, community collaborations were central to the work of Rivers of Steel, including the partnership behind the debut of a new pocket park in Monongahela, shown here during opening festivities on the Fourth of July.

Embedded Community Programs

In recent years, Rivers of Steel has expanded its collaborative footprint by working on multiyear projects with individual communities. First among these has been a live music and entertainment series created in partnership with Homestead Borough and Steel Valley Accelerator. Homestead Live Fridays was comprised of six events in 2023 that brought together small businesses and nonprofits to present live music, arts experiences, and community camaraderie.

Creative placemaking is sometimes a term used to define this type of intentional work when / where the arts are used to create vibrancy in a location, and it is also a tenet of how Rivers of Steel works with communities in our National Heritage Area.

Earlier this year, Rivers of Steel launched a new effort called the Creative Leadership Program, borne out of the creative placemaking concept, that resulted in a new parklet in the City of Monongahela. And while Rivers of Steel is committed to working with its partners in Mon City for at least two more years to help increase vibrancy in their downtown corridor, we’ve also just launched a three-year program with partners in Brownsville, Pennsylvania.

The 48-Inch Universal Plate Mill from the Homestead Works is being reassembled as part of a workforce development program that is part of the Partners for Creative Economy initiative.

Partners for Creative Economy

Rivers of Steel’s collaborative work in Monongahela and throughout the Heritage Area sets the stage for its newest initiative: Partners for Creative Economy, which was announced this fall with support by a POWER grant from the Appalachian Regional Commission.

By bringing together artists and designers with community groups, local governments, and heritage tourism organizations, Rivers of Steel aims to build creative leadership, provide career opportunities in historic trades, and turn towns into destinations for visitors.

Five key strategies, including the creative leadership program, joint program partnerships, collaborative marketing efforts, a new workforce training initiative, and an expanded Mini-Grants program, will advance the community-based work that Rivers of Steel is already engaged in.

It’s a dynamic new vision for the region, one that builds on the foundation created through partnerships and collaborations like those we just shared.

A community barbecue during Homestead Live Fridays brings residents together around brisket and pasta.

2024 and Beyond

With support from Rivers of Steel’s efforts over the intervening decades, the City of Pittsburgh has changed what it means to be a postindustrial community. However, for too many places up and down the river valleys, communities are at risk of being left behind.

Rivers of Steel is committed, now more than ever, to work collaboratively and creatively with partners to help build whole, vibrant, livable communities.

As we chart the ways in which we will support this community work in the coming years, we recognize that none of these efforts happen without community support.

Be a part of this work by making a donation to Rivers of Steel today, or make a gift during Give Big Pittsburgh on Tuesday, November 28, 2023.

When you support Rivers of Steel, you are not just supporting one organization; you are supporting communities throughout southwestern Pennsylvania.

Thank you for being a part of the Rivers of Steel community.

Carly V. McCoy is the director of marketing and communications for Rivers of Steel.

With a passion for lifelong learning, Carly’s role as director of marketing & communications for Rivers of Steel allows her to draw from her experiences, both professional and personal, to amplify the many assets of the Pittsburgh region—celebrating its history, heritage, artistry, and innovation of its residents to encourage heritage tourism, community engagement, and economic revitalization.

Her previous articles include The Historic Preservation of the Carrie Blast Furnaces and A Decade-Long Journey for a 120-Year-Old Building.

Jon Engel is the Heritage Arts Coordinator for Rivers of Steel and the author of the Heritage Highlights column.

Jon Engel is the Heritage Arts Coordinator for Rivers of Steel and the author of the Heritage Highlights column.

Gita Michulka is a Pittsburgh-based marketing and communications consultant with over 15 years of experience promoting our region’s arts, recreation, and nonprofit assets. Read her prior article on 2023

Gita Michulka is a Pittsburgh-based marketing and communications consultant with over 15 years of experience promoting our region’s arts, recreation, and nonprofit assets. Read her prior article on 2023

Gita Michulka is a Pittsburgh-based marketing and communications consultant with over 15 years of experience promoting our region’s arts, recreation, and nonprofit assets.

Gita Michulka is a Pittsburgh-based marketing and communications consultant with over 15 years of experience promoting our region’s arts, recreation, and nonprofit assets.

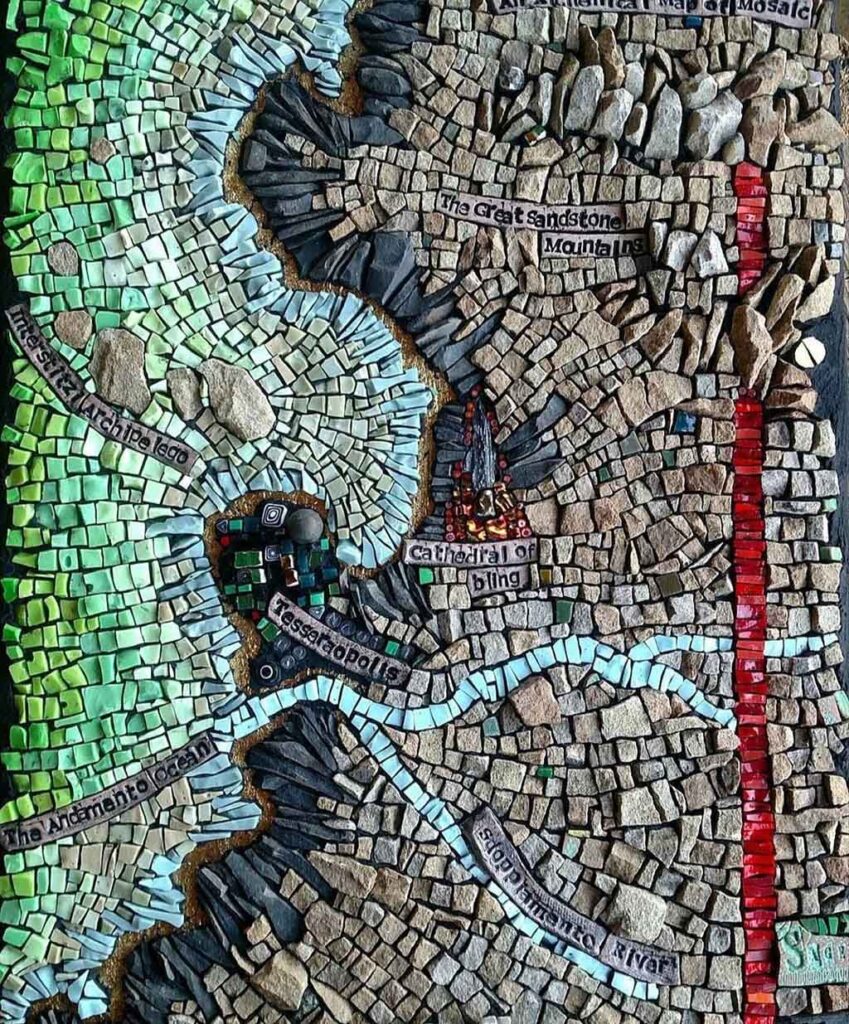

Rachel Sager, The Storytelling Mosaicist, has been making mosaic, writing about mosaic, speaking about mosaic, and teaching mosaic for over twenty years. Her signature forager and intuitive teaching styles have changed how mosaic is experienced and have helped build on the golden age that the art form is enjoying in these exciting decades.

Rachel Sager, The Storytelling Mosaicist, has been making mosaic, writing about mosaic, speaking about mosaic, and teaching mosaic for over twenty years. Her signature forager and intuitive teaching styles have changed how mosaic is experienced and have helped build on the golden age that the art form is enjoying in these exciting decades.

Red Dog: The Storytelling Stone

Red Dog: The Storytelling Stone