Meet John Mahn, Jr.

If you’re looking for John Mahn, Jr., the odds are good that you’ll find him outdoors and near a body of water—preferably with a fishing rod in hand.

His favorite local spot these days is Cross Creek Lake in Avella, where John and his then eight-year-old daughter, Brandee, were among the first to cast a line when it opened for public fishing in 1985. He spends a lot of time on the Monongahela River—John’s last name happens to sound the same as its nickname, the Mon—because it’s so close to his home in Charleroi. The part of the Youghiogheny River near his home runs slower and shallower than in other areas, making it good for wading. John knows a lot of great fishing holes “all up and down I-79,” and if he follows it north to Erie, he can take the boat he has docked there out on “the big lake.”

Growing up as a youngster in Cambridge, Massachusetts, John’s draw to water was just as strong, but his options were considerably more limited. “It was a city; we didn’t have creeks running everywhere like in Pennsylvania. There was the Charles River, and that was about it,” John says. He quickly figured out that the best fishing in town was at the local water supply lake, which were all ringed with ten-foot fences topped with barbed wire. “They had blue gills, sunfish, and bass in them, though, so if I wanted to fish, I’d sneak under one of the fences and hide in the bushes to fish from there.” His parents also helped him experience the great outdoors whenever the opportunity arose. “My dad wasn’t a fisherman. He wasn’t outdoorsy or anything like that—but he was into whatever his kids were into,” John says. “My older brother was into scouting, so my dad got into scouting. I liked to fish and run around in the woods, so my mom and dad made sure I got plenty of that. I went to church camp, I went to scout camp, I went to YMCA camp, and I even went to the Jewish community center camp.”

He remembers the impact that those experiences had on him as a child, shaping him into the person he is today. Retired from a 35-year career as a supervisor in the steel industry, John is heading into his eleventh season as a deckhand on Rivers of Steel’s Explorer riverboat, having joined the crew when the vessel was owned by RiverQuest. Explorer was built as a floating classroom, and it typically welcomes 3,500 students on board every year to participate in hands-on education programs. In a region that is defined by river valleys, creeks, and waterways, for many students these field trips are their first experience on the water.

“The first thing they ask me is, ‘Where is the poop deck?’” John laughs. “They all want to see the poop deck, and I have to tell them that we don’t have one. Then they see [Explorer’s Captain] Ryan [O’Rourke], or they see me, and they say, ‘You mean you can actually make money working on a boat?’” It’s an eye-opening experience before the education programming even begins. “I think about it every time we have those kids on the boat,” John says. “They have so much available right in front of them, and some of them are clueless about the opportunities that they have. It’s kind of sad in another way, because I think about some kids like me who never get the opportunity, and this is right in their back yard.”

John Mahn, Jr. and Magisterial District Judge Eric Porter pose for a picture together after John’s swearing in to the Pennsylvania Fish and Boat Commission in December, 2021.

Connecting Kids with the Outdoors

Connecting kids with the outdoors is one of John’s top priorities in his newest role as a Commissioner appointed by Governor Tom Wolf to the Pennsylvania Fish and Boat Commission. Appropriately, John made sure Washington County Magisterial District Judge Eric Porter, who John used to take fishing when the judge was young, swore him into the position. “He was a classmate of my son John Wesley’s, and when he was little the only way I’d get him to go fishing with me was to take a friend with him.”

The Fish and Boat Commission is an independent state agency with a mission to protect, conserve, and enhance the Commonwealth’s aquatic resources and provide fishing and boating opportunities. John will serve as a commissioner for the next four years representing District 2, which includes Allegheny, Armstrong, Beaver, Fayette, Greene, Indiana, Washington, and Westmoreland counties. John will serve not only the current anglers and boaters in his district, but also those who have yet to realize their passion.

“I told our executive director the other day the Pennsylvania Fish and Boat Commission is so far off of these kids’ radar. If you’re growing up in Homestead or Braddock, the Fish and Boat Commission might as well be on the moon it’s so far away from you,” says John, who is working on an initiative with the agency that would bring conservation officers and outdoor recreation instructors into classrooms to talk about all of the ways to enjoy time in nature. “Something that always sticks with me is the idea that talent is evenly distributed, and opportunity is not. There is no doubt that there are some future outdoorsmen and outdoorswomen sitting in the schools—they just have to get the opportunity to get outside,” John says. “Some of them will grab it and run if they’re given the chance. The worst thing you can tell a kid is ‘You’ll never be able to do that,’ or ‘We don’t do this.’”

Left: John Mahn holds up a norther pike in Ontario, Canada. Right: John Mahn shows off a lobster on his friend’s boat, off the coast of Cape Ann, Massachusetts.

A Life Filled with Firsts

Limiting preconceptions like those held no water in the home John grew up in or in the life that he’s shaped. At age 71, John is the first man of African American descent appointed to the Board of Commissioners, a stride that begins to make the agency more representative of the population it serves—particularly at a time of increased scrutiny of the barriers that people of color face when accessing the outdoors are encountering increased scrutiny. But being the first or only Black person in a space is nothing new to John.

“I understand the significance of it, and I want other people to understand the significance of it—but to me, it’s not a big deal because I’ve run into it so much in my life,” John says. “If there was something I wanted to do, I wasn’t going to let anyone else tell me that I couldn’t do it. I love to fish, and I would go to different places to fish, and I would run into the same thing—people who’d say that you can’t stay here. Well, I’m here, I came here to fish, so I’m going to find a place to fish. I never let that bother me. I would do what I had to do.”

John’s mother modeled that same mentality and determination while he was growing up in the 1960s, whether participating in sit-in demonstrations at the local Woolworth’s lunch counter or insisting that her sons be educated alongside white students at the local public school. “There were only two high schools in Cambridge, a vo-tech school, and Cambridge High and Latin School,” John explains. “If you were Black and you were a boy, you were going to the vo-tech because you weren’t going to college.” But that wasn’t going to be the case for the Mahn boys—their mother engrained the notion that they would be college graduates before they were old enough to understand what college was. John’s older brother, seven years his senior, was one of the first two Black males to attend High and Latin in the early 1960s. John couldn’t help but notice that his brother came home from school with torn shirts and black eyes almost daily during that first year. It also didn’t escape his attention that his own elementary school principal—who lived across the street—drove past him every day as he walked to school. “When I went to school my classes were integrated, but when I went home the neighborhoods weren’t,” John says. “I didn’t know it at the time, but we were redlined. I never thought much about it, that his side of the street was white, and on my side of the street it was all Black. And I didn’t know about redlining at that time. All I wondered was how come Mr. Murphy sees me every day going to the same school he’s going to, it’s wintertime—why didn’t he offer me a ride?”

Shortly after John’s older brother graduated from High and Latin and began his studies at Franklin & Marshall College, their mother passed away. John was in eighth grade at the time, and also had a younger sister. “A single parent back in those days was almost unheard of,” John recalls. “My dad now had three kids and a job [as a machinist] to handle.” The Fox family, who had employed John’s mother as a domestic, helped his father formulate a plan to enroll John in a boarding school just south of Boston. With John’s older brother away at college, that would leave only his little sister at home.

The year he started at Milton Academy, he was one of the first three Black students admitted in the boarding school’s history—one in eighth grade, himself in ninth grade, and another in tenth grade. “For myself, I think the Jewish kids had a lot harder time of it than I did,” John says. “I remember people saying the N-word, not directly at me, but within earshot. As far as being treated differently or being treated poorly, I didn’t remember that as part of the experience.”

It was during these years that John began to realize his love for boating, joining his friends on their families’ boats and cruising from Boston to Maine. “Every day was like an adventure,” he recalls. “You never knew who you were going to run into, you had to plot a course, you had to navigate by compass and buoys. You never knew right where you were. You might sail all day and never see another boat.” John also worked on a lobster boat during high school. “There was a lobsterman, and we said we were helping him, but we were just in his way, really. He put up with us and let us haul the traps,” John recalls.

Eager to see more of the world outside of Boston and Cambridge, John followed his brother’s path to attend Franklin & Marshall College in Lancaster, Pennsylvania, in 1968. The school became co-ed while he was a student there, so his younger sister also enrolled there when she graduated from high school. Finding adventure in the great outdoors remained a priority for John, and he spent the summer of 1971 in a Rambler on an epic road trip with high school friends. They headed west across the United States and then back east via Canada, camping in National Parks and staying with friends and family along the way.

John, his mother-in-law Maxine, with his wife Jeannie celebrate the holidays.

Making a Home in the Mon Valley

Another thing John found in college: love. John and Jeannie met while attending a friend’s wedding in New York City—he was a friend of the groom, and she was a friend of the bride, and soon they were married themselves during John’s junior year. “When I graduated, it was time to figure out what we were going to do. She wanted to stay in New York, and I just could not do it—I am not a city boy. We couldn’t afford to move back to Boston. So, reluctantly, she agreed that we could move back here,” he said, referring to Jeannie’s hometown of Charleroi. “We’d visited many times while dating, and there was a strong outdoor tradition that I was into.”

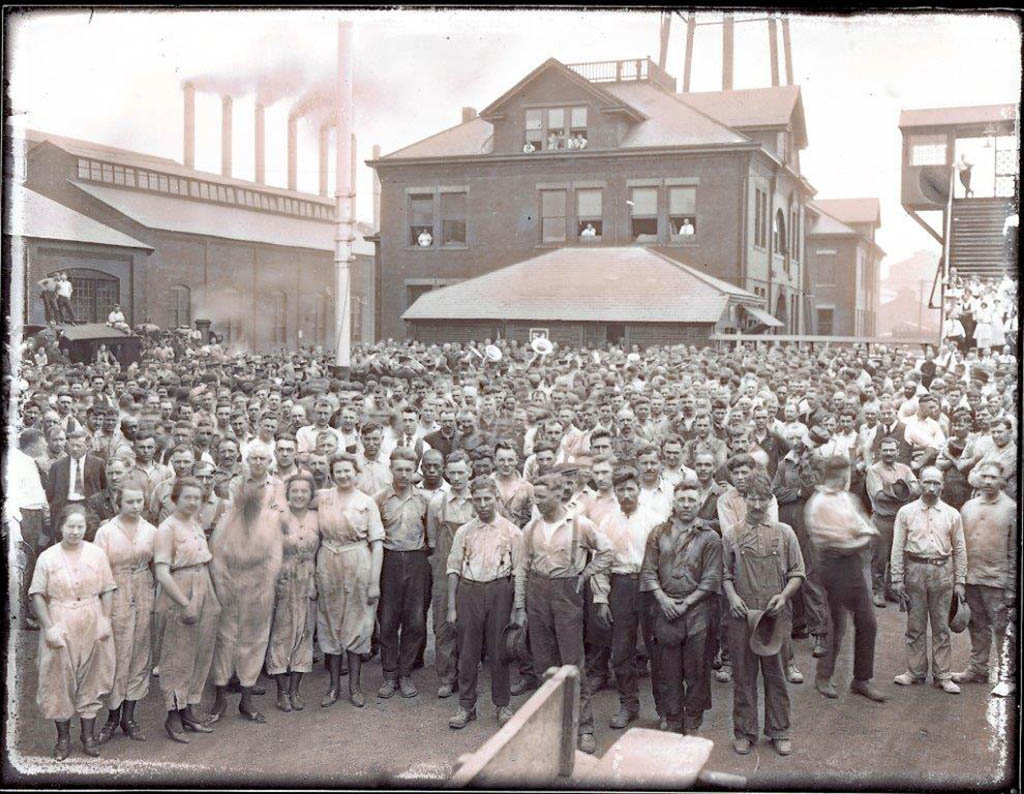

Jeannie ended up moving back ahead of John, and her father helped her get a job in human resources at Wheeling-Pittsburgh Steel Corporation’s Allenport Works, where he worked as the only Black supervisor among about 3,000 employees. When John arrived in Charleroi to join Jeannie, the young couple lived with her parents at first. His father-in-law let John know that the plant manager at the Allenport Works was aiming to hire another Black supervisor who had a college degree. “I’m sitting at the table eating his food, and he’s telling me that so-and-so’s looking for a worker—so I figured I better try it. And so I went and had the interview,” John says.

John landed the job, and he and Jeannie moved to an apartment in little California for about a year, about ten miles from where they’d been living with her parents. “My wife is from a very large, tight-knit family, and she felt it was too far away from them. She wasn’t seeing her family as much as she wanted to be, so we bought a house in Charleroi so she could be closer to them,” John says.

By the late ’70s, John Wesley and Brandee were born, and Jeannie left her job at Wheeling-Pittsburgh to raise their children. John advanced through managerial positions at the mill over the course of a thirty-five-year career. “I can’t say anything bad about the mill. I bought a house, I put two kids through school. It was a good living, and it served our needs,” John says. “I ran the roll shop until I retired, and I was the supervisor the whole time. The one thing I liked about it was that the majority of the guys I supervised had the same interests that I did. I wasn’t a golfer, so I didn’t golf—but it seemed like everyone that worked under me was either a hunter, a fisherman, or a boater. So when I was off, I was always doing one of those things.”

Some of the men who John managed weren’t interested in finding common ground, however. “Once Jeannie’s dad retired, I was the only Black supervisor in the mill.” And while this wasn’t a new experience for him, he saw clear differences between the way that the mill workers reacted to his presence and the way his fellow students had treated him in school. “Adults are sometimes not afraid to express their true selves. I had to supervise guys who didn’t take kindly to me giving them orders, and they made that known . . . Let’s just say the Mon Valley wasn’t the most enlightened workforce. The guys worked hard. They had hard jobs—they had hot, dirty, uncomfortable jobs to do. I give them credit, but there was also a small minority that spent more time trying to get out of work than if they’d just done the job to begin with. I got an education in college, but I also got an education of a different kind in the mill.”

That discrimination extended in the community outside of the mill, where many organizations and establishments made sure John knew he wasn’t welcome. “As much as I love to hunt and fish, I could never figure out why the gun clubs and sportsmen’s clubs were always full and never accepting members. When it came time to teach my kids about the outdoors, those kinds of facilities weren’t available to me. But I made sure they learned what they needed to and had those kinds of experiences. When my son was young, I bought a boat and took him fishing,” John says. “To this day, there’s a place two streets over from my house that I can’t walk into and get a drink. This is 2022, and I can’t walk in there and get a drink.”

It’s a reality that’s strikingly similar to his wife’s recollections. As a high schooler in Charleroi in the 1970s, she was not permitted to eat inside restaurants; Blacks were refused a seat and received their order in a bag to go. “Technically, they weren’t denying you service, but you’d have to take it somewhere else to eat,” John says.

His father-in-law faced even more blatant racism in the early 1980s, when he met with a group of fellow former mill employees at the local Italian Club. “It was the early ’80s, and the company—business was bad, so they laid off the union guys. But the people who were on salary and were managers were just fired. It worked out that all the guys who were let go were older, so they got together and hired a lawyer from Detroit to fight age discrimination,” John says. “They had one meeting, and the president of the club went up to them and said, ‘You can meet here again, but he’s not getting back in here,’” referring to John’s father-in-law. “This was twenty or thirty men meeting there for two or three hours drinking. I give the other guys a lot of credit, because they took their business elsewhere.”

John, with a wrapped head to protect himself from the sun, displays a bonefish in the Bahamas.

A Life Outdoors

Even as intensity inside the mill and the injustice outside of it remained present, the outdoors was still a steady constant in John’s life. “You go in the mill, and it’s hot, it’s noisy and dirty. So you need—or at least I do—some adventure in my life,” he says. “When you get in the outdoors, when you go fishing, you never know if you’re going to catch something or not. It’s all unknown, and it’s something you have very little control over. That sense of adventure is what the outdoors is all about for me.”

As a freelance outdoors writer for the Mon Valley section of the Tribune-Review newspaper’s Sunday edition, he captured that sense of adventure for readers for about thirty years. He’s also a past president and current member of the Pennsylvania Outdoor Writers Association. “Doing that for so long, I got to see a lot of kids being introduced to the outdoors—not just fishing, but boating, camping, and hiking.”

One outdoor experience he’ll never forget is a fishing trip in New York on Lake Ontario with his then thirteen-year-old daughter Brandee, which turned out to be a good reminder of the surprises that can come along when they’re least expected. As they were casting their lines, Brandee asked her dad if he would get her fish mounted if she caught a big one. “I thought, ‘What are you going to catch?” so I said, ‘Sure,’” John remembers. “Well, I had to get it mounted, and it’s still hanging on the wall. That was in 1991, and it’s bigger than any fish I’ve ever caught! I still kid her about that to this day.”

John Mahn, Jr. during a charter excursion on the Explorer riverboat, 2021.

Working on the Water

In the early 2000s, John returned to his native state and earned his Coast Guard license to run a passenger boat at the Massachusetts Maritime Academy on Cape Cod, where he was once again the only Black student in the class, and this time one of the oldest. That license would come in handy when the mill he worked for closed in 2009, bringing an end to a 35-year career in steel industry management. Before long, he was behind the wheel of Miss Pittsburgh, a 50-foot enclosed pontoon boat, shuttling passengers to sporting events in Pittsburgh. His work with this company ended up taking him far beyond the three rivers. When the owner purchased a new vessel, Fantasy, in 2010, John signed up for what he thought would be a two- or three-week voyage to bring it from New York City via the Hudson, across the Lake Erie Canal, and into Pittsburgh via the Ohio River.

With his bags packed with warm clothes for October weather on northern waterways, John and the rest of the crew were surprised to find out that the Fantasy was too tall to go on the Erie Canal when they arrived in New York. A new plan was devised to bring the boat out to the Atlantic Ocean, heading south to connect into the Intracoastal Waterway. After cutting across Florida on the Okeechobee Canal, Fantasy redirected North to enter the Tennessee-Tombigbee Waterway in Mobile, Alabama. From there, the crew navigated to the Mississippi, and finally to the Ohio River and its destination in Pittsburgh. “That was a long, long trip,” John recalls, noting that Fantasy’s top speed was around ten miles per hour. “We would stop every night, and on Sundays we’d find a Steelers bar wherever we were, and then we’d get on our way. Towards the end, we’d go around the clock and take shifts because it was taking so long.” The crew was flown home for Thanksgiving, and then resumed the voyage. John eventually had to return home by the time the boat had made it to Tennessee, but he was waiting in Pittsburgh to greet his fellow crew when they arrived in Pittsburgh. “That was an adventure, to say the least. That was one of the things that you got into having no idea what is going to happen,” John says. “You think one thing is going to happen, and it’s nothing like that—it was 180 degrees different than what I expected.”

By 2011, John’s fellow captain on Miss Pittsburgh, Curt Graham, let him know that he was getting slammed with hours at his other job piloting the Explorer riverboat for RiverQuest. John didn’t need much convincing to start training on that boat to help his friend out. Sadly, after about six months of training, John was diagnosed with prostate cancer in 2012. “I took forty-some radiation treatments, and you have to go every day to get your radiation. By the time I got out of those treatments, there was no way I could [also continue training],” John says. When he returned to Explorer later that year in remission, the boat was fully staffed with captains. “I didn’t want to quit, so I decided I’d just take a deckhand position. I was still out on the water.”

More than a decade later, John remains a constant fixture on the Explorer, assisting with deck operations, handling the lines, keeping watch for traffic and obstacles, and working with the rest of the crew to maintain a safe and welcoming environment on the riverboat—even if it does lack a poop deck, to younger passengers’ dismay.

“I love that job,” John says. “I don’t tell [Captain] Ryan, but I would probably do it for nothing.”

A Literary Look is a recent series that features recommended reads from the Rivers of Steel. For Women’s History Month, Dr. Kirsten L. Paine, our site management coordinator and interpretive specialist, reflects on one of her favorite historic Pittsburghers—Jane Grey Cannon Swisshelm. Working as a reporter, newspaper publisher, women’s rights advocate, and abolitionist throughout the nineteenth century, Swisshelm was a woman ahead of her time. Using her autobiography as a starting point, Dr. Paine leans on her own expertise in literature from that era to provide context for understanding this pioneering woman.

A Literary Look is a recent series that features recommended reads from the Rivers of Steel. For Women’s History Month, Dr. Kirsten L. Paine, our site management coordinator and interpretive specialist, reflects on one of her favorite historic Pittsburghers—Jane Grey Cannon Swisshelm. Working as a reporter, newspaper publisher, women’s rights advocate, and abolitionist throughout the nineteenth century, Swisshelm was a woman ahead of her time. Using her autobiography as a starting point, Dr. Paine leans on her own expertise in literature from that era to provide context for understanding this pioneering woman.

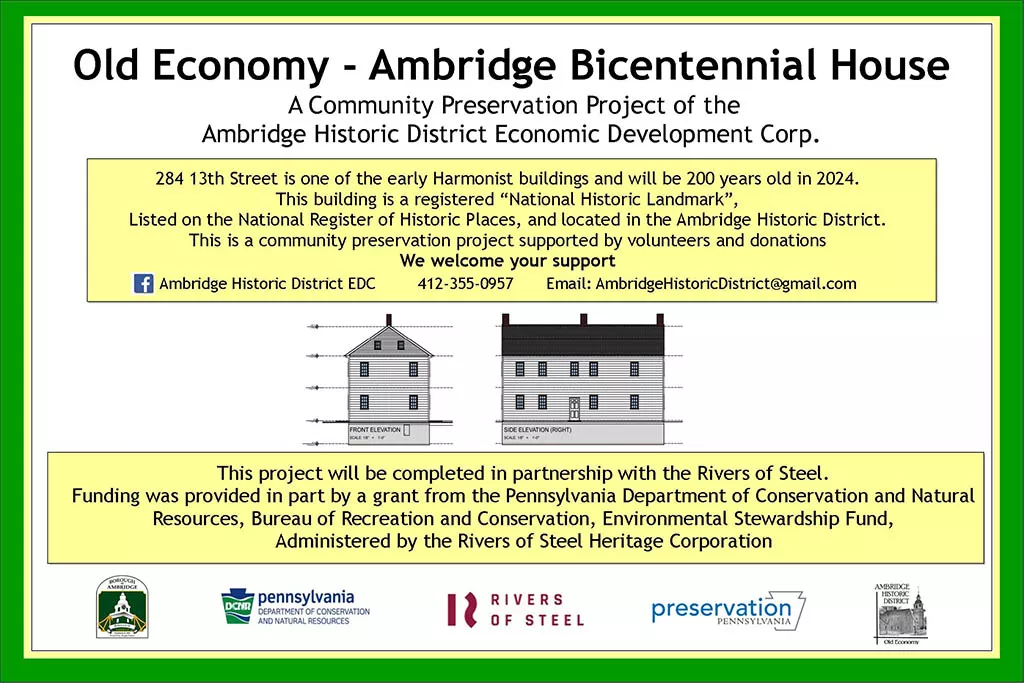

The Ambridge Bicentennial House: A Community Preservation Project

The Ambridge Bicentennial House: A Community Preservation Project

Brianna Horan is the manager of tourism & visitor experience at Rivers of Steel, where she helps groups design customized travel experiences throughout southwestern Pennsylvania. She also lends her considerable writing talents to this blog on occasion and can often be found on the Explorer riverboat, where she manages Rivers of Steel’s public tours and private charter experiences.

Brianna Horan is the manager of tourism & visitor experience at Rivers of Steel, where she helps groups design customized travel experiences throughout southwestern Pennsylvania. She also lends her considerable writing talents to this blog on occasion and can often be found on the Explorer riverboat, where she manages Rivers of Steel’s public tours and private charter experiences.

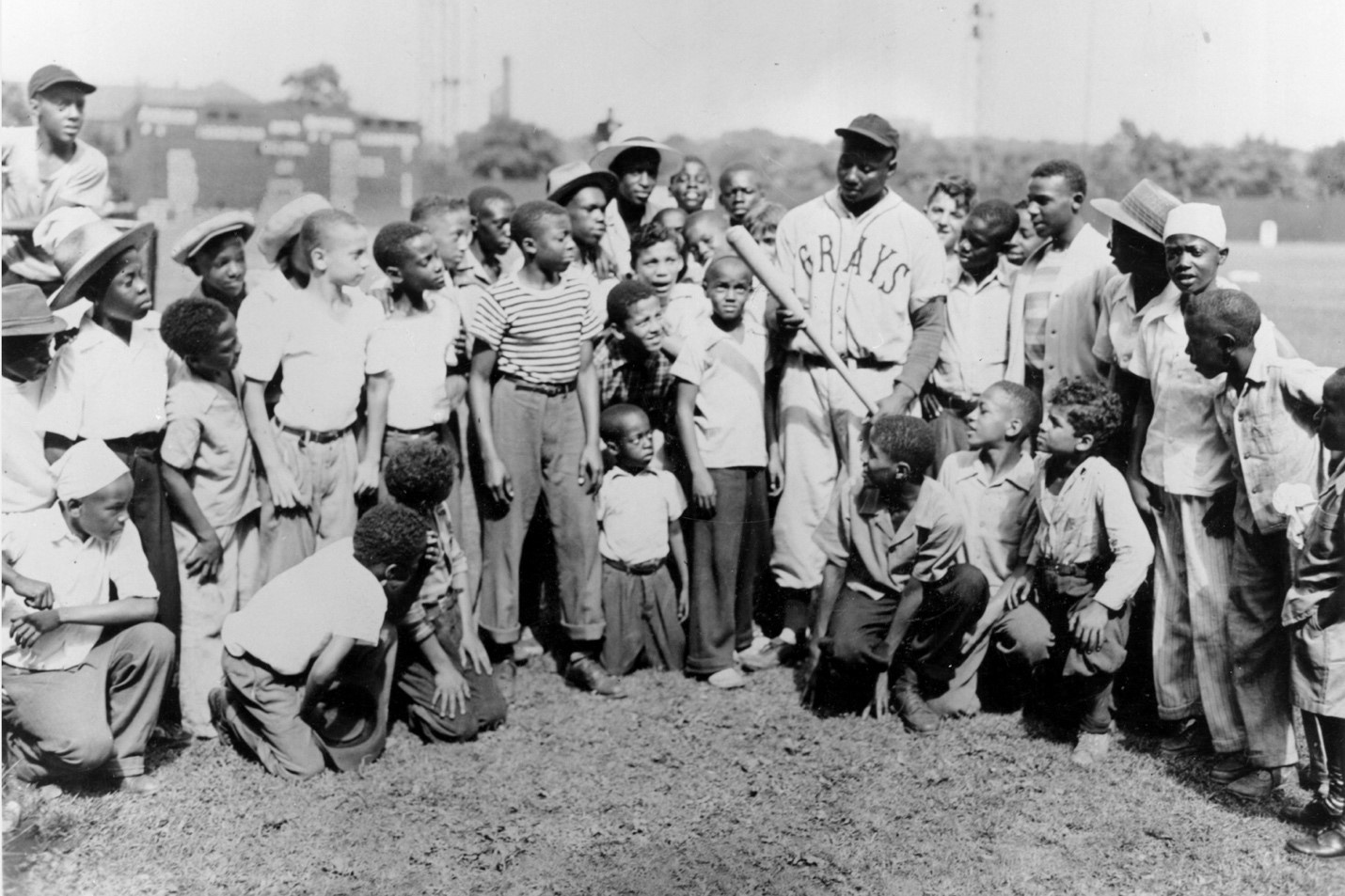

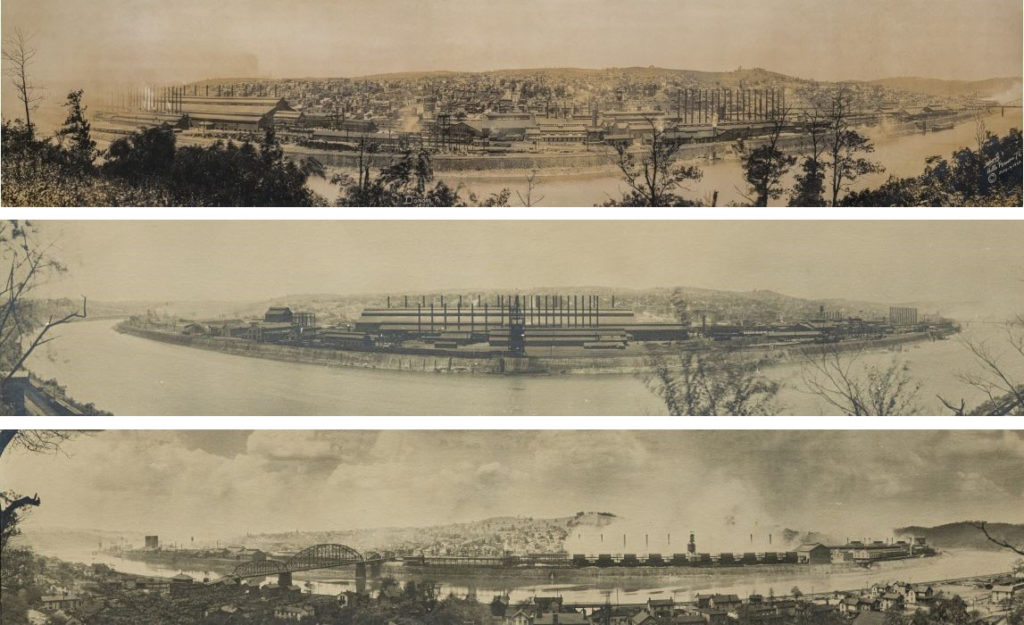

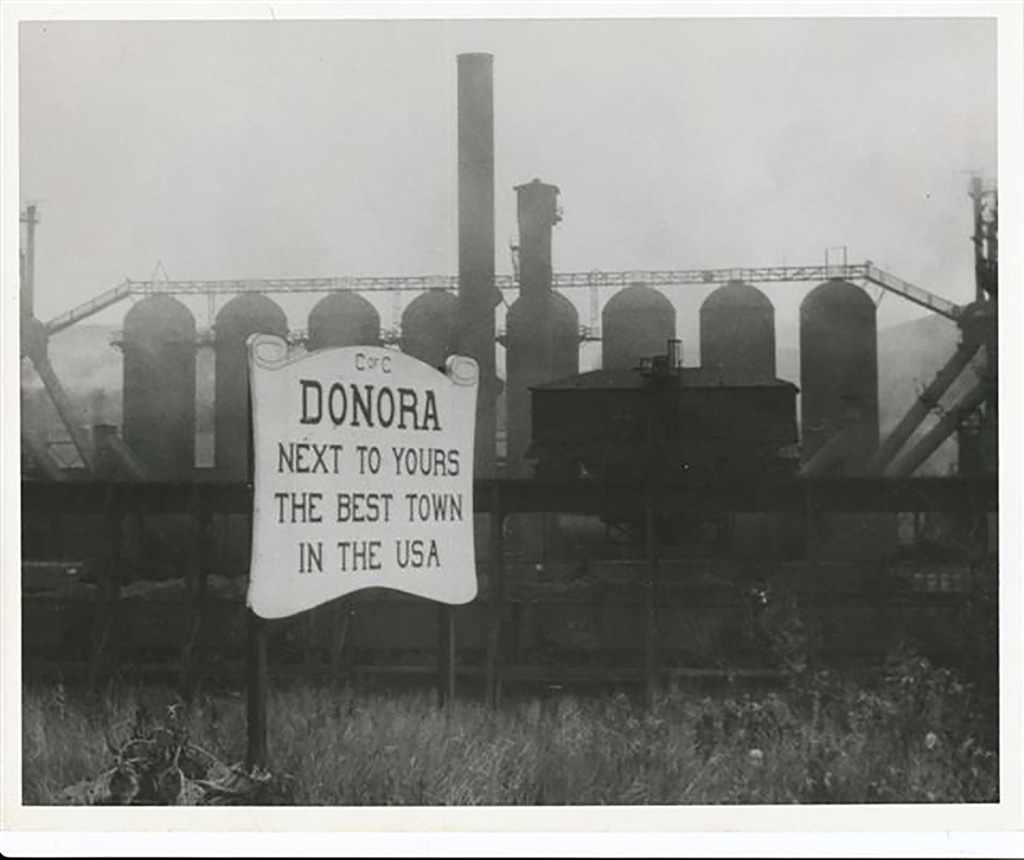

Donora Historical Society’s Bruce Dreisbach Collection Opens a Window to Everyday Life in the Early 1900s

Donora Historical Society’s Bruce Dreisbach Collection Opens a Window to Everyday Life in the Early 1900s

“Rivers of Steel is thrilled to play a part in the long-term conservation of this wonderful collection of glass plate negatives within the Donora Historical Society’s holdings,” said Ron Baraff, the director of historical resources and facilities for Rivers of Steel. “The story that their collection unveils of life in the mill is a wonderful complement to the rich archival holdings preserved by Rivers of Steel and other area repositories. Partnerships such as these, through our mini-grant program and regional cooperation, allow for all of us to tell, more succinctly, the enduring industrial and cultural history of our region and its legacies’ impact on the nation—and the world.”

“Rivers of Steel is thrilled to play a part in the long-term conservation of this wonderful collection of glass plate negatives within the Donora Historical Society’s holdings,” said Ron Baraff, the director of historical resources and facilities for Rivers of Steel. “The story that their collection unveils of life in the mill is a wonderful complement to the rich archival holdings preserved by Rivers of Steel and other area repositories. Partnerships such as these, through our mini-grant program and regional cooperation, allow for all of us to tell, more succinctly, the enduring industrial and cultural history of our region and its legacies’ impact on the nation—and the world.”

By Jonathan Engel

By Jonathan Engel