A Literary Look at William Attaway’s Blood on the Forge

A Literary Look is an occasional series that features recommended reads from the Rivers of Steel staff. For Black History Month, Dr. Kirsten L. Paine, our site management coordinator and interpretive specialist, introduces us to William Attaway’s Blood on the Forge, a 1941 novel primarily set in Homestead in 1919 that connects us with the lives of characters uprooted by the Great Migration. In the process, Paine explores one of Pittsburgh’s contributions to the Harlem Renaissance artistic movement and how it reveals some of the cultural and socioeconomic aspects of our region’s heritage, offering an understanding of Black life in the mills and the industrialized communities that surrounded them.

By Dr. Kirsten L. Paine

Setting the Scene

“I got the Weary Blues

And I can’t be satisfied.

Got the Weary Blues

And can’t be satisfied—

I ain’t happy no mo’

And I wish that I had died.”

—“The Weary Blues” by Langston Hughes (1925)

“Thump, thump, thump, went his foot on the floor.” The speaker, an unidentified spectator in Langston Hughes’s landmark poem, “The Weary Blues,” watches a Black musician wring love and sorrow from a piano in a Harlem bar. The music swells up in bodies cast in shades of blue and yellow; it is mournful, yearning, and melodic, its rhythm incessant. It carries the piano player from the bar, to the street, and finally to his bed, where he dreams about that melody some more.

That melancholy rhythm echoes throughout William Atwell’s novel, Blood on the Forge. The loudest strain comes through at the end of the story as a train carries Melody Moss away from the Homestead steel mills. He sits opposite his brother, Chinatown Moss, and watches him talk with a soldier. Their older brother, Big Mat Moss, is gone.

The soldier says to Chinatown, “There’s one thing I couldn’t shut out” (Attaway 236). Chinatown responds, “What was that?” (236). The soldier bids him, “Listen” (236). Over the puffing engine and creaking cars, the men hear, “Boom! … Boom! … Boom! …” (236). The rumble emanates from their bones—a memory from one kind of battlefield or another, one kind of war or another—but Melody cannot hear it. He just knows his brother can feel it, so he feels it, too. The train rolls toward Pittsburgh. When Chinatown and Melody arrive in Pittsburgh without their brother, they need to go to a place called “the Strip,” where the brothers can disappear into the crowd and try to begin their lives all over again (235).

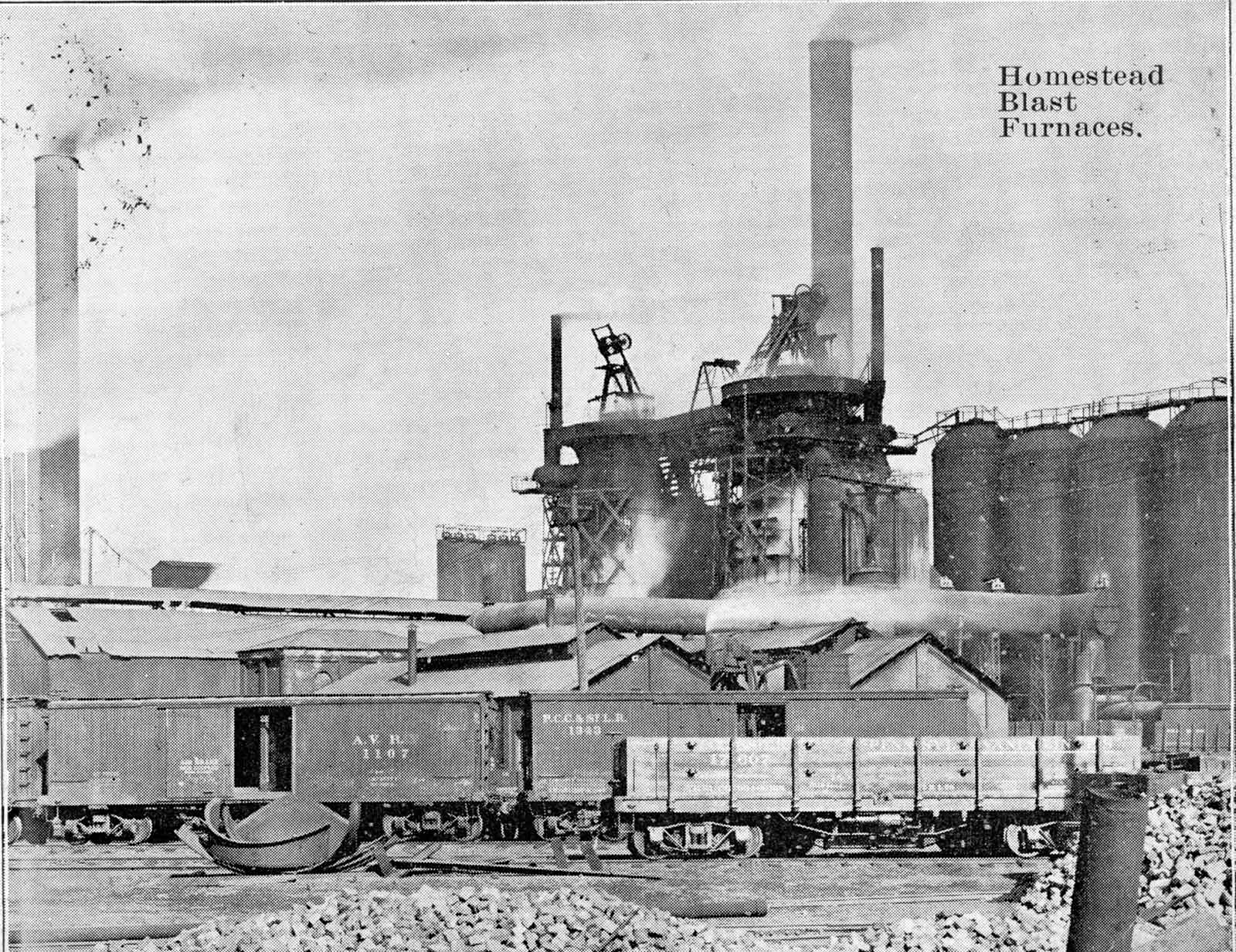

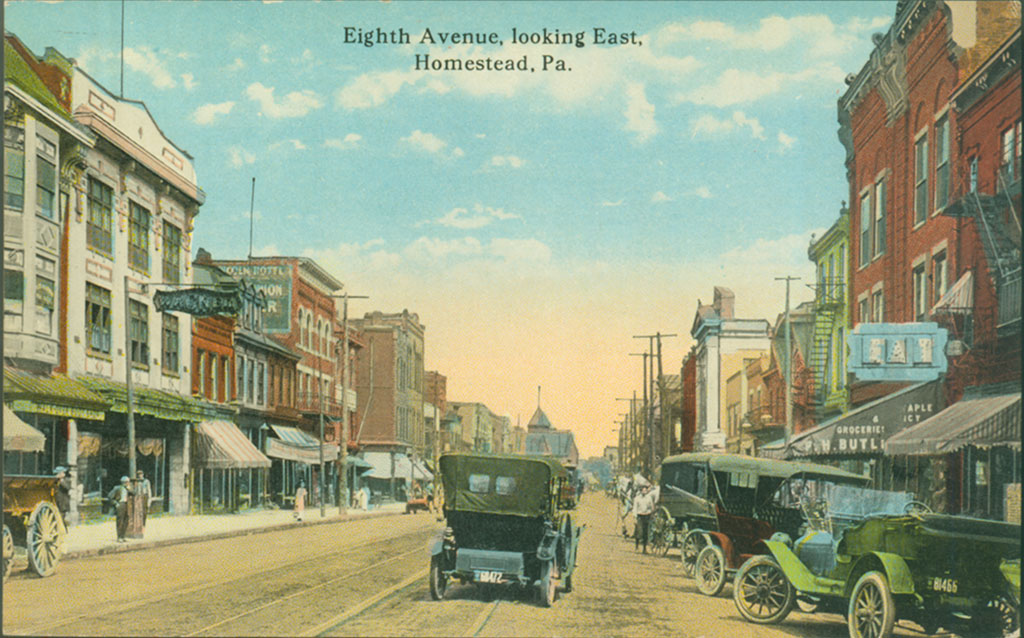

A view of Homestead, Rivers of Steel Archives.

The Journeys of the Moss Brothers

This moment is from the final scene in William Attaway’s novel, a masterpiece first published in 1941, Blood on the Forge. This blistering, harrowing, and deeply tragic novel chronicles the intertwined journeys of the three Moss brothers: Big Mat, Chinatown, and Melody. The Moss brothers are sharecroppers on a farm in Kentucky in 1919, and they each dream of a bigger life for themselves.

One evening, a strange white man on a horse gives Chinatown and Melody ten dollars from a roll of cash. He promises them more. Much more. However, the Moss brothers must meet him at the station and board a freight train bound for points north. As Chinatown and Melody debate whether or not this offer is a prank—or worse—they start to wonder if there “must be a lot of that kind of up-North money,” and whether or not they could have some of it for themselves (33). While Melody and Chinatown see an opportunity for each of them to prosper, Big Mat needs convincing. The three brothers ultimately crouch on a hay-strewn boxcar floor and dream of a new life as the train takes them northward.

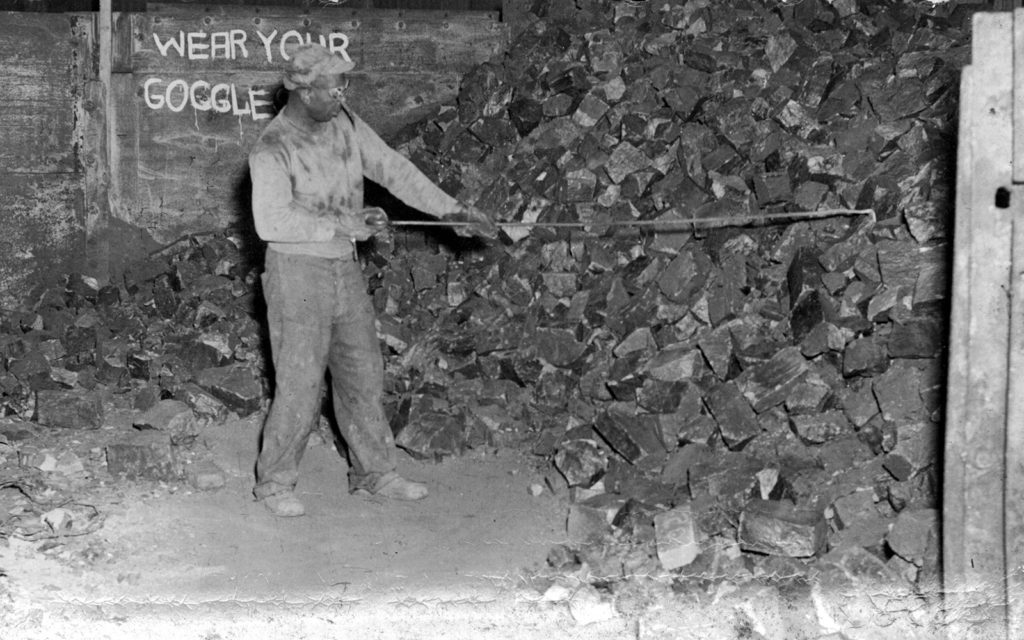

What the Moss brothers discover, however, is not money. Instead of a rolling Kentucky field, the roiling Pennsylvania steel mill looms ahead. The prosperity suggested by the sight of the jackleg’s roll of cash reveals itself as bug-infested bunkhouses, brothels, and the looming shadows of Jim Crow. Mill work is easy to come by, but it is both extremely dangerous and underpaid. Despite his size, Big Mat tries not to let the physical punishment grind him down. He forges ahead, sometimes too far away for his brothers to see.

Melody carries on, picking the Blues out of his guitar, trying to keep mind, body, and soul intact. When he plays “so all those long days he had been twisted inside,” Melody cannot help but feel the emptiness in his music (123). The guitar “sang all the empty notes it had,” and makes him think “it was a bad thing to have to play only the music inside him” (123). The Blues wail, but Melody does not heed the song. In fact, none of the brothers listen.

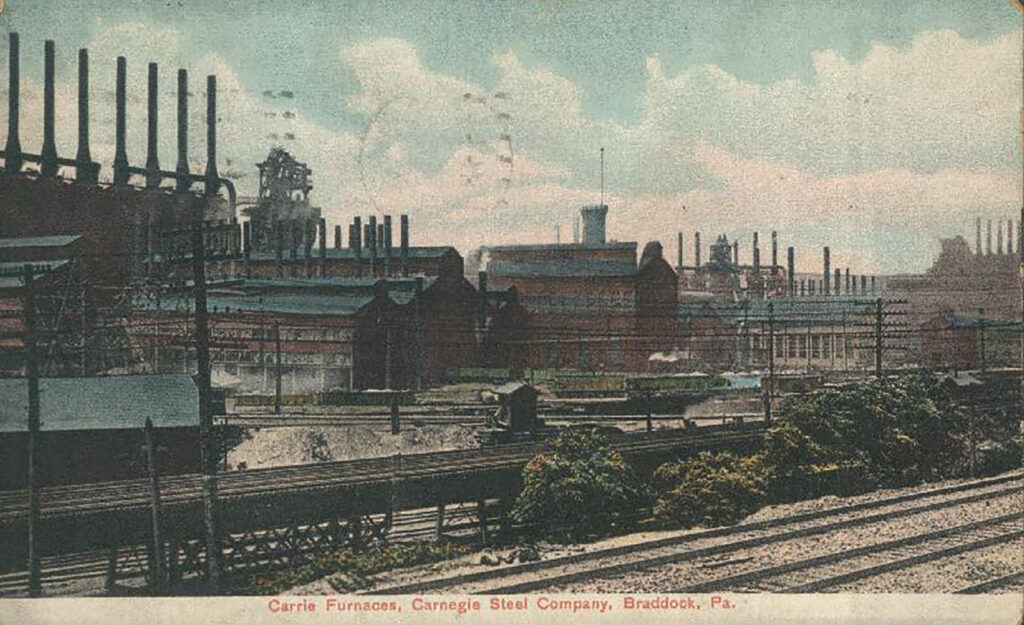

A postcard of Homestead in 1916, Rivers of Steel Archives

The Great Migration

The Moss brothers represent parts of a much larger early twentieth-century movement now known as the Great Migration. The Great Migration maps the mass exodus of African Americans from the South to the North, and it is one of the largest and most concentrated movements of people in American history.

The first wave of the Great Migration occurred between 1910 and 1940. It occurred in the midst of global tumult caused by two World Wars, economic instability and collapse, the influenza pandemic, and unfettered mechanization, weaponization, and technological revolution. Masses of people moved across countries and continents. As waves of European immigrants came into the United States, large numbers of Americans also crossed state and county borders.

African Americans searched for stability, safety, and opportunity in new climates, new environments, and new communities. Northern industrial cities in particular, with burning and churning factories creating the modern world, beckoned newcomers. Chief among them, New York City, Boston, Chicago, Detroit, and Pittsburgh grew fast, ran hot, and enveloped people from the moment they disembarked from a boat or a train. When they arrived in cities like Pittsburgh, however, African Americans often faced familiar racist power structures limiting their economic opportunity. While Black workers could find jobs aplenty in the coal mines, coke plants, blast furnaces, steel mills, and rail yards of the Monongahela River Valley, those jobs were often in the most dangerous locations with the lowest wages. In many instances, Black workers came north because they were promised a good, steady factory job but were instead used as strikebreakers. These strikebreakers were summarily dismissed after white workers returned, which often left them without resources in an unfamiliar city, hundreds of miles away from any place that resembled home.

A train brings the Moss brothers from Kentucky to Pennsylvania. From a few peepholes in the boxcar’s sides, they catch glimpses of the landscape emerging around them. As the train slithers along, the valley looks as though a “giant might have planted his foot on the heel of a great shovel and split the bare hills” creating a trench (43). From that trench rise mills, “half buried in the earth”(43). Off to the side the brothers see a “a dirty-as-a-catfish-hole river with a beautiful name: the Monongahela” (43). Instead of swirls of green and blue, “its banks were lined with mountains of red ore, yellow limestone, and black coke. None of this was good to the eyes of men accustomed to the pattern of fields” (43). Their hopes of a new home turn into piles of garbage, acrid smoke, ash, and the constant vibration of machines. Very quickly, readers attune to the music in this story.

A worker moving manganese, Rivers of Steel Archives.

The Reality and Rhythm of a Working Class Novel

Over the course of Blood on the Forge, Big Mat, Chinatown, and Melody Moss endure oppressive systems and racist violence, which questions what all that “up-North money” could possibly cost them in the end.

In an article about literary depictions of the ways in which factory owners used Black laborers as strikebreakers, Cynthia Hamilton, former director of African American studies at the University of Rhode Island, describes what drives men like the Moss brothers: “These men were driven by forces within: their old standards of self-reliance and self-sufficiency, their unyielding nature in the face of force, and their traditional conceptions of manhood, which centered around a silent tolerance and endurance of pain and the constant desire for respect. Ironically, the combination drove them, helplessly, into the arms of capital, which transformed all of these motives into profits for the owners and bosses” (Hamilton 158).

As a reader, I often find myself compelled by characters who succumb to inevitable tragedy or characters who conjure feelings of sympathy despite their horrifically unsympathetic actions. Blood on the Forge compels me as a reader precisely because I have never, and will never, have to experience a life remotely close to the violence the Moss brothers endure. Unlike most of the texts in my library, Blood on the Forge is not sentimental fiction; meaning it does not bank on overwrought emotional scenes in order to move a reader or spur them into action. Rather, this novel is a realist novel in that the language Attaway uses is straightforward, unvarnished, and evident in everyday surroundings. It is also a working-class novel, sometimes called the proletarian novel, which emerged as an influential genre in the early twentieth century. Working-class writing centers on the lives and desires of laboring people, and it often exposes the inequalities and excesses of capitalism. The story affects me because it requires my attention to the language. I cannot turn away from the bloodshed because the reasons for this bloodshed are not swathed in simile or metaphor. As a reader, I think this is hard, but I also think this is why Blood on the Forge is worth seeing through to the end.

I come back to the music in Blood on the Forge, the Blues. I listen to Melody’s songs and let them tell me the story within the story, and I find a rhythm that way. In the darkness Chinatown and Melody tell stories to each other as a form of camaraderie, and at one point, Chinatown asks Melody to pick up his guitar again. He says, “Blues drive away that hungry cravin’[…] I jest sit here in the warmth and listen” (Attaway 163). Melody begins singing a song about snakes, and for the first time in a while, he “thought a little and let his thought ride high through the endless spades of his mind. He hit a bad chord on his music. But it was good enough to carry him on a bit” (164). An accident at the mill cost Chinatown his sight, so Melody becomes his brother’s eyes. Another accident at the mill cost Melody use of his picking hand, so he learns how to play and sing the Blues again. The Moss brothers move through their world like a Blues song in search of a home.

People create homes everywhere. People establish neighborhoods, cultivate communities, and anchor their identities to experiences and environments in order to tell their stories. In many instances, those stories are haunting and tragic, and they bear witness to violence, its aftermath, and the soul-deep scars it leaves behind. That does not mean we should turn away or otherwise disengage from it. Sometimes it means we should look more intently and read with even more openness, especially if it means reconciling visions of home and community with the painful losses endured in the quest to find these places of restoration and respite.

Suggested Reading

Blood on the Forge is a traditional migration story, but it also fits in with art from the Harlem Renaissance. There are so many ways to read Blood on the Forge in conversation with other literature from its time, and I highly recommend using the novel as an anchor for lots of literary exploration. I suggest pairing Blood on the Forge with Thomas Bell’s Out of This Furnace, also published in 1941. However, if readers are in search of the Blues in poetry, delve into Langston Hughes’s work. Consider collections like The Dream Keeper and Other Poems (1932), A New Song (1938), or Fields of Wonder (1947). For novels about movement, migration, and the search for identity, try Zora Neale Hurston’s Their Eyes Were Watching God (1938) and Moses, Man of the Mountain (1939), Jean Toomer’s Cain (1923) or Richard Wright’s Native Son (1940). If the “play’s the thing,” then seek out Lorraine Hansberry’s A Raisin in the Sun (1959) or any work by Pittsburgh’s own August Wilson.

Dr. Kirsten L. Paine is an educator and researcher with more than a decade of experience working in higher education. She started working for Rivers of Steel in 2017 as a tour guide at the Carrie Blast Furnaces National Historic Landmark and was inspired by the mission to preserve such a national treasure held in public trust. Kirsten is committed to the work of public humanities education in her role as Site Management Coordinator and Interpretive Specialist. By creating and facilitating public programs that make the National Heritage Area’s history come alive for the community, she believes in archival study and teaching from primary sources as vital community resources.

Dr. Kirsten L. Paine is an educator and researcher with more than a decade of experience working in higher education. She started working for Rivers of Steel in 2017 as a tour guide at the Carrie Blast Furnaces National Historic Landmark and was inspired by the mission to preserve such a national treasure held in public trust. Kirsten is committed to the work of public humanities education in her role as Site Management Coordinator and Interpretive Specialist. By creating and facilitating public programs that make the National Heritage Area’s history come alive for the community, she believes in archival study and teaching from primary sources as vital community resources.