Interview Excerpts

Can you talk about how the Ciloets organization came to be in the midst of a male-dominated industry, and how that might have changed over the years?

Lisa Roudabush (LR) : When you think that in the 1940s, there was a women’s organization at a very male-dominated, manufacturing company—in essence, one of the first women’s affinity groups. And now you see a lot of affinity groups in companies nowadays—women’s organizations within in companies, and U.S. Steel had one since the ’40s, which I think is tremendous. And it was certainly a tremendous opportunity for women to explore the company outside of their area, and learn about the company from executive speakers. The mill trips were, I think, one of the biggest components of the Ciloets organization where you got to go and see how the steel was made, and meet a lot of people in the company that maybe you wouldn’t otherwise—whether you were a male or female, actually, you wouldn’t have had that opportunity.

I came in in the early ’80s as an engineer, and again there were not many female engineers at the time. I think that there’s been a lot of growth in [the employment of] women. The plants are still very male dominated. I was the first female general manager of the Mon Valley Works, I was the first female plant manager of Clairton, so that was unique, I guess, but it’s still male dominated, though there were a lot of parts of the organization that have really flourished and promoted women.

Bonnie Galla (BG): In audit, when I started, it was all male. There wasn’t one woman. And when I retired, I have to say at least half or three-fourths were women management on the workforce there. I think more towards the end of when I worked, you saw definitely more women coming in to different positions… When I started there were six administrative assistants in the department, and those were the only women. Eventually, as those six retired, I would take over their positions. Then I was the only admin for the audit department, and we had offices, probably when I started, in 14 different cities that were under headquarters. Then, when I retired, we only had the headquarters office left, in Pittsburgh.

Donna DeBone (DD): I started in 1964 and, as I mentioned earlier, I started in the personnel services department at headquarters as a secretary. I was attending evening school at Pitt working toward a degree at the time, and I did complete those degree requirements as time went on. The personnel services department was a very large department at the time, covering many aspects of personnel and labor relations, and there were very few women in management at that time in the department. After several secretarial positions, I was moved to an entry-level management position, and again, both in our department, personnel, and throughout the corporation, there weren’t a lot of women, even at the entry level. Because U.S. Steel—and I would expect also with Alcoa, Westinghouse, they were all desirable corporations to work for—we actually had women who came in with college degrees onto secretarial positions, and some of them ended up on executive secretarial positions. But the doors were beginning to open for women, and when I was promoted to the position of Manager of Human Resources a number of years later, there was only one other female manager in the personnel services department. She was an older woman; she worked in the training area.

So, as I look back at my own career, I’ve seen a lot of change in that 50-year period. But also looking at it from the perspective of having worked in the personnel human resources department, I look back at how hiring changed. U.S. Steel had traditionally hired into the corporation for management positions at the management trainee level, and they were looking for people with the technical degrees, the science, engineering, business, financial degrees. And back in those early years, women weren’t really majoring so much in those fields, so it was difficult with the recruiting. As I look back to my high school years, the women who excelled in the math and science areas generally went into teaching. That was the way they could use this field that they loved. But slowly things did begin to change, both within and on the outside, so the company was looking on the inside to move women to advance. They were attempting to hire more women. There was a lot of competition for U.S. Steel on the outside as they were hiring, too. These women that had the technical degrees were being recruited by other companies also and, I don’t know how Lisa feels, but we found that sometimes the steel industry wasn’t as attractive, maybe, to women in those early days as some of the other companies. But, the company began to move women over the years, advance women that were in the corporation—Lisa gave some examples of what has happened over the years, and she certainly is an example of the changing role of women in the corporation.

There is one interesting story—I think we’ve all heard it and maybe just quickly can tell you—there was a woman who, this goes back to the ’50s, she is deceased now, but she spoke several times with Ciloets to tell us of her hiring experience with US Steel. She had a law degree and she lived in the Cleveland area, and she applied for a job in the Cleveland law office. The attorney who headed up that office wanted to hire her, but he told her that he could not hire her as an attorney, but he could hire her as a legal secretary, and he would give her work in the legal field, which he did. And he actually became her mentor. She spent the rest of her career with U.S. Steel; she ended up in Pittsburgh in the headquarters’ law department as a senior general attorney, so it was a story that we were always interested in that kind of showed the change that occurred over the years. I think she was an assistant to the general council, so she reached a nice level within the corporation.

Were there ever discussions in terms of hiring certain quotas, that you wanted to make sure that a certain number of women were considered for certain positions, or overall a certain percentage of the workforce should be female—was that ever a topic of discussion?

LR: … I don’t know that there was any quota per se, but certainly during the ’80s there were a lot of women that were being hired in all departments. I remember when I started, as a management associate, our class of management associates were very diverse with lots of women. But a lot of women didn’t stay in the steel industry. It is especially tough in the plants, in plant operations and plant maintenance, and working shifts was not as appealing, and you know, women had opportunities when there were very few women who were engineers; they had a lot of opportunities at different places that maybe, as Marylin said, had a nicer work environment, for lack of a better term. It’d be one thing working downtown in an office setting. It was a little bit different in the mill—a little bit later in terms of increasing amounts of women in the organization.

Marylin, could you share what your experience was like in research?

Marylin Roberts (MR): I started at U.S. Steel in August of 1966, and when I was hired, I worked in the employment office for quite a few years there. It was basically bringing in people to be interviewed. I did a lot of testing for the clerical part of it. I’d always been in an admin position at the research center. During the years working there, I got into a position where we had a group of ladies that were hired, and they were more or less put into a secretarial group, so they were trained then to move on to the different divisions—the technical divisions. So, when there was a position opened in the division, they would interview these five or six ladies that were already being groomed to be going out into those positions—which makes sense, because if an individual retires or leaves, or whatever, she gets married, then they’re hiring from within and they’ve already had some training as far as the procedures and the things they would have to do and be responsible for in any secretarial position. And then as some women would go out to an area, then they would look at the process of hiring new female positions. … When they would come in—not a lot, but there were several ladies that really wanted to move on. They were going to night school, they were getting in position to hopefully get their degree in some type of an engineering background. A lot of these ladies would go into a technician job, and still continue their education and then once they got their degree, they could move on to another position in the organization, which was very—I think they were great in wanting to pursue their career that way.

I actually, for my 46 years that I worked at research, I never worked in technical division. It was always through the administration part, and then my job when I retired in 2003, I was the training coordinator for research, organizing, coordinating, setting up for the engineers. And I really learned a lot—even in a clerical position, and I think that’s what the Ciloets really was a great organization for. At that time back in the ’40s, for these women who were in the clerical field to really try to understand what the engineers were doing, either in their office as an engineer, and out at the plants. So, back then that’s how it really started. These ladies wanted to know more about what they were doing in the office working for these engineers. And over the years, [women with technical positions] came into the organization. They took in people from the plants. So we had a mixed group of people that we had friendships with them, but we also learned among a lot from them, too. It was a nice career that I had at U.S. Steel. I wouldn’t have given it up for anything. It was wonderful, and like I said, staying in the field that I was in, I was very happy in the jobs that I had in research.

What’s the balance of how much of a professional development organization versus a social organization the Ciloets has been for its members. With the opportunity that the organization offered to tour different plants and locations, it must have been a way for members to see all of the different experiences that were available at U.S. Steel. In what ways did it help women or change the course of their careers?

MR: I think a lot of the ladies really strived to get ahead if they could, and it was hard because, like I said, some of the secretaries back then that even wanted to be a technician—they actually had to be able to lift [a certain number of] pounds. They were going to be out in the lab area working with the other engineers and other male technicians, and I saw quite a few move on—either staying in that job or moving on to a position as an engineer.

LR: The Ciloets really … started out as a group of women who got an opportunity to take a training class to learn about steel, and that was set up by the company. They loved it so much and learned so much that they kept it together and spread that to other women. And the fact that the educational piece—we always had at a minimum two U.S. Steel speakers a year. The discussion was on topics of the company: what they were doing, the big projects, how they ran their organization—and the women in the audience were, one, very interested in learning about the organization; number two, asked amazingly great questions. They were very knowledgeable about what was going on at U.S. Steel.

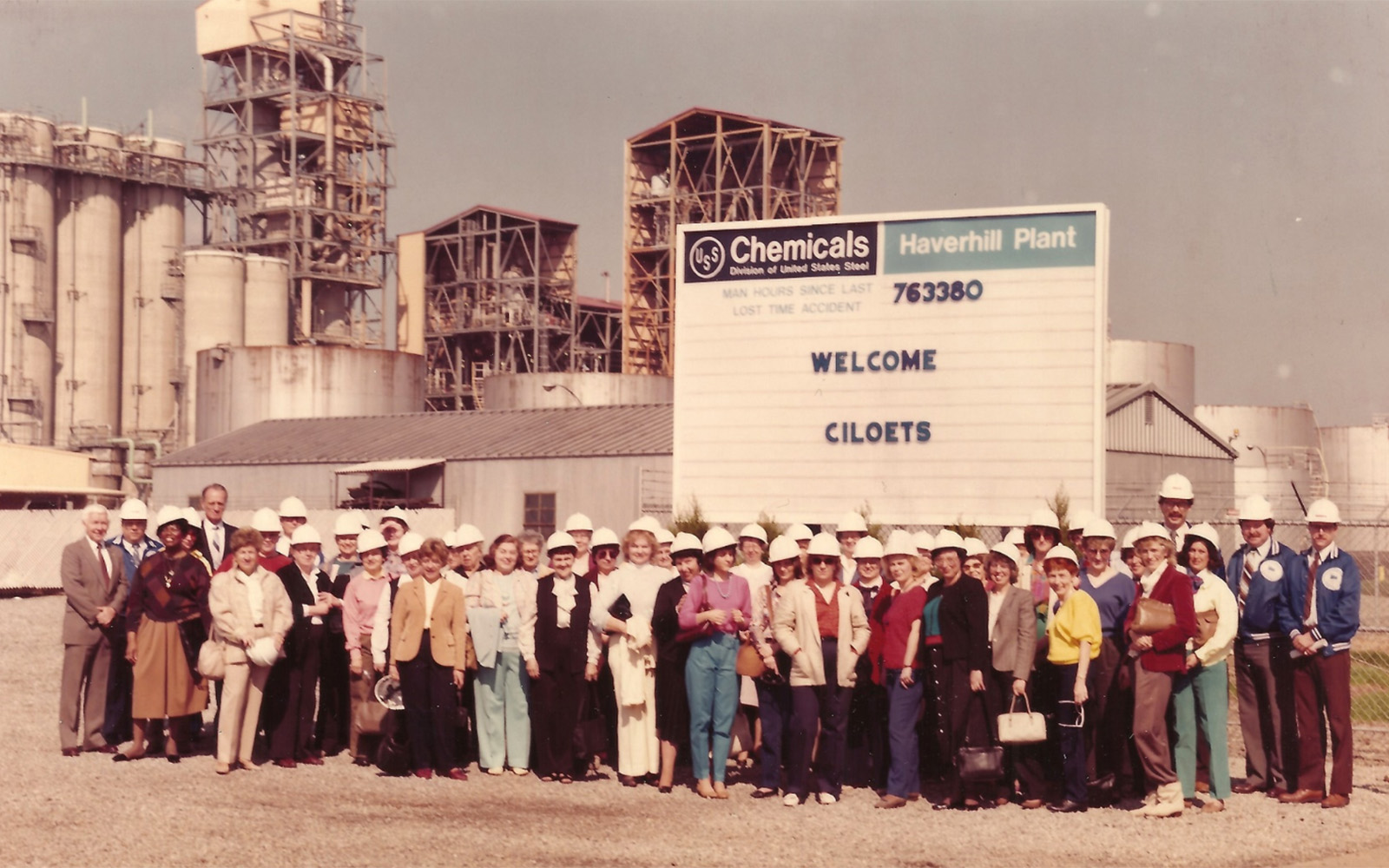

The mill trips again were another opportunity where you may be working with a mill or a plant, or other offices as Donna or Bonnie had mentioned, that were scattered all over the country but you never got an opportunity to meet face to face. Well, here was an opportunity where the women went to Chicago, they went to Washington, they went to New York, they went to Birmingham, Alabama—they went to all the plants and got to see how the steel was made. They got to interact with the people that they probably only heard of.

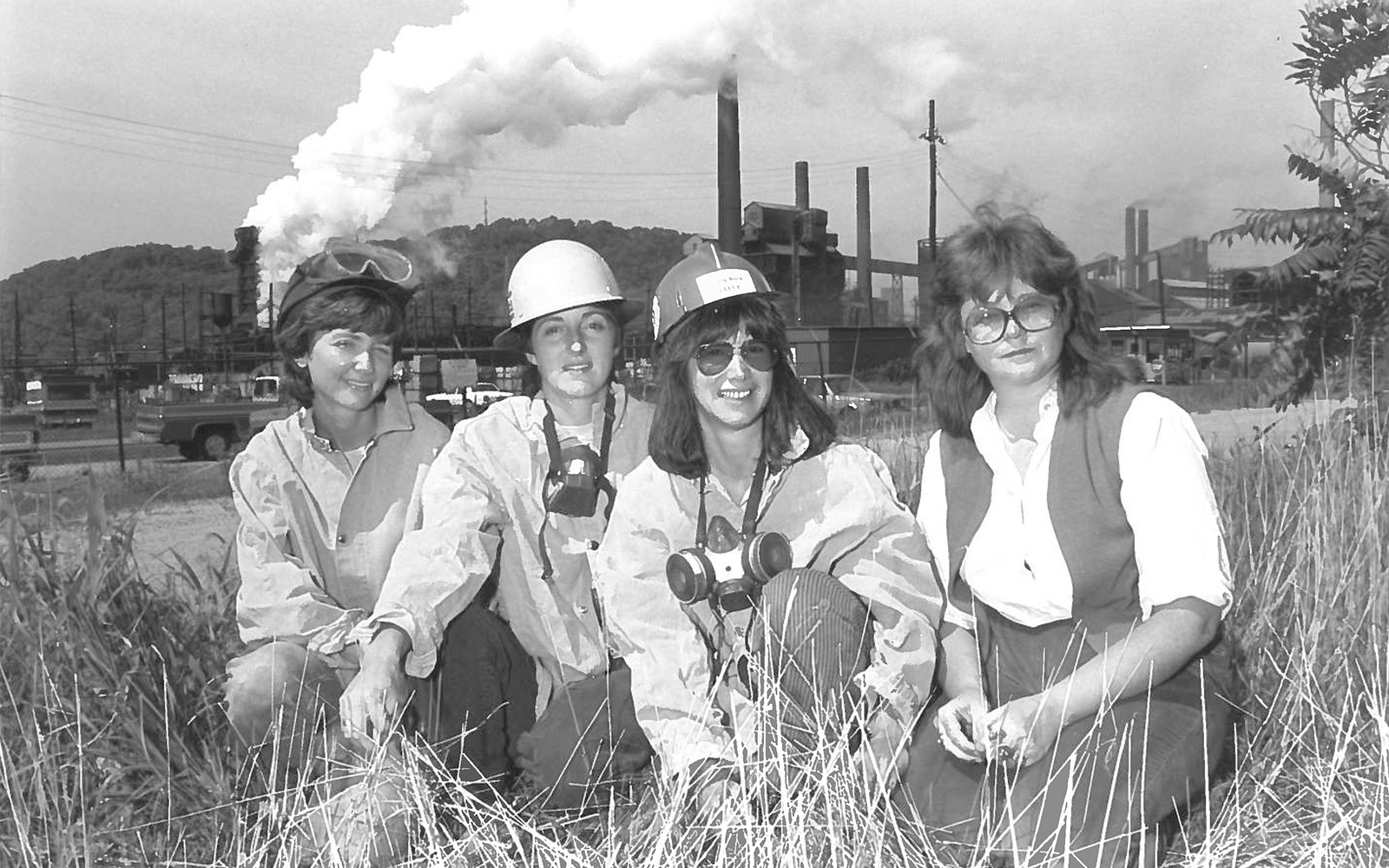

The Ciloets trip to U.S.S. Chemicals at the Haverhill Plant in 1986.

But the other big thing about the Ciloets was that it was a pretty big organization. At one point we had way over 300 members, and it was run by the women… All the meetings were organized by women who volunteered for these leadership positions and committees And there were some very large, complicated organizational activities that were done by the Ciloets. Charity work, just the set-up of the meetings, the set-up of the mill trips. And it gave these women an opportunity to be in a leadership role, and maybe learn those aspects that they could take back to their jobs. To have to speak publicly, and interact and network with lots of different organizations and people both within the company and outside the company to bring in speakers. So, I think the Ciloets gave women that outlet to expand their leadership skills in an area near work, but kind of outside of work as well. A lot of this stuff was done on your own time.

When you think out about the different committee positions and leadership roles with the Ciloets, and starting out as members as well, what are some of your favorite memories—whether the connections and friendships you made, or speakers that you heard from that really changed your perspective on things? The mill trips sound like they were really unique, one-of-a-kind experiences as well.

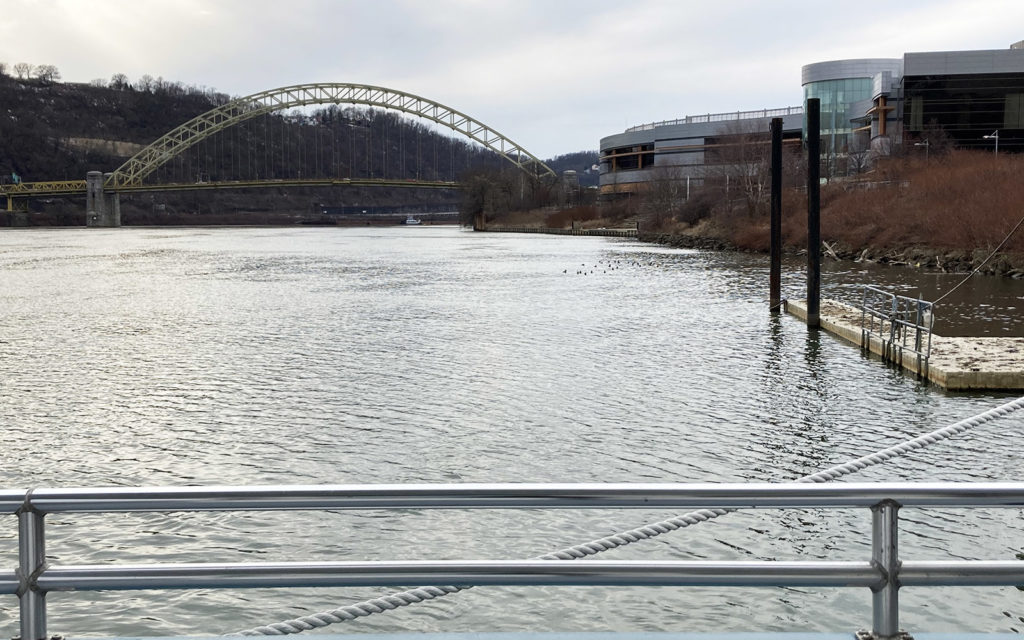

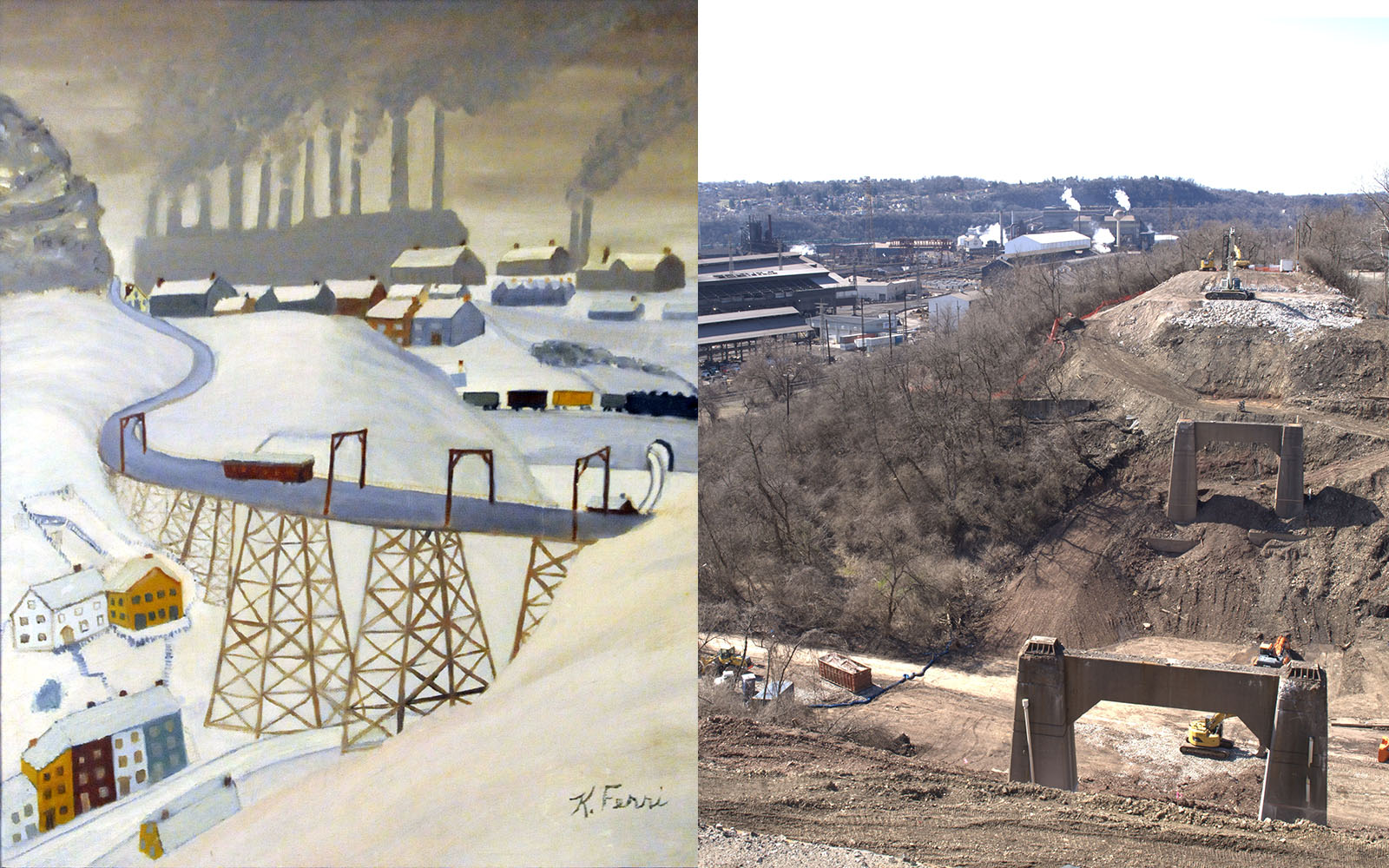

BG: I have to say, I think the mill trips were just above and beyond, and Donna chaired them for many, many years. I used to help her. I remember [when I] worked in headquarters, and [other staff from headquarters would visit the auditor office in Gary] and say, “Gary Works is a city within itself,” and you just couldn’t picture how huge this place was. Then, when we did a mill trip there and I got to see it. It sits on the lake, surrounded by these other steel tech companies, it is just massive. It’s beyond what you could even imagine. And then also going to the [Monongahela River] Valley and seeing them make the steel and pouring the steel out of the big ladles; and that was so huge, and you can’t even imagine these men currently and back in the day doing this. That was very impressive, but I don’t even know if they would even take people through today with the safety rules. We were fortunate enough back then that they would take the women through. I don’t know if they would do that anymore. And also, the railroads, I have to say the topography of going through the Valley and how the train moved, and moved the product to the different plants—that was interesting, because growing up in the Valley, you don’t even realize all this until you actually go and tour these places and see it. So those were interesting, and I think of the camaraderie with the women to this day.

The Ciloets outside of U.S.S. Gary Works in Indiana, 1999.

In finance and auditing, you might not necessarily need to know how to make steel, or how railroads move things from one place to another—but when you got back from a mill trip and had that wider knowledge, how did that effect how you did your work?

BG: Typing your reports, and some of the stuff you’re typing you’re not sure what it means, but then you tour the plant and they explain things to you, it all comes together and makes sense. It was a learning experience.

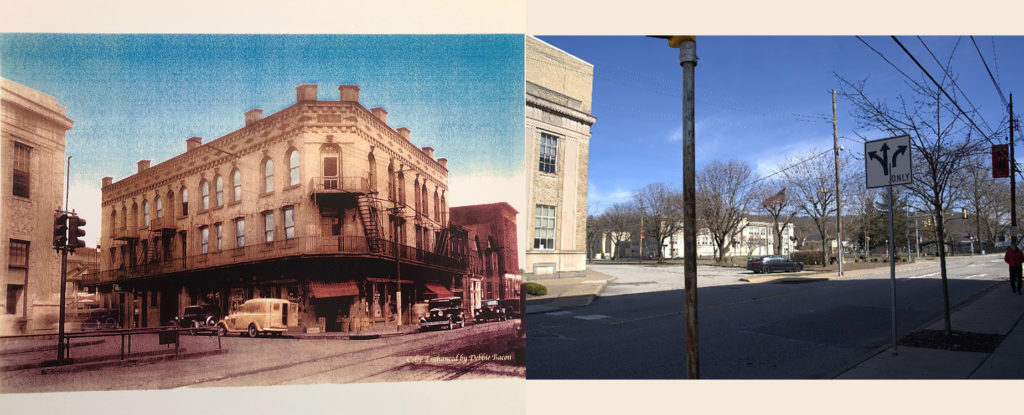

DD: I can tell you that our members always looked forward to hearing where the trip was going to be. That was the big question—where the trip was going to be this year. We always tried to announce it months in advance. Our program year ran September through May, and we generally took the trip in spring, usually in April. We alternated between a one-day, local visit to a U.S. Steel facility in the area, and a weekend trip for the following year. For the local trips, we visited all of the plants, so those that are still in existence—Irvin, Edgar Thomson, Clairton, National, Homestead, all of the area plants were visited probably several times over the many years. We went to Youngstown, Johnstown, Lorain—we even went underground—U.S. Steel has some employees at the Annandale Archives in Boyers, PA, so we did have an opportunity to do some things that other people just didn’t have an opportunity to do.

On the weekend trips, we generally left on a Thursday afternoon, spent Friday visiting the facility, hosted by the organization, usually a wonderful day. Then we would spend the rest of the weekend wherever we were visiting. These weekend trips were to Gary, Indiana; Fairfield, Alabama; Minnesota Ore Operations. In addition, we had government affairs offices in Washington, D.C., and Harrisburg, so we visited there. There were financial offices in New York City, so that got us to New York. Bonnie mentioned the two international trips; those were done in recent years. When U.S. Steel bought the Steel Company of Canada we went to Hamilton in Ontario and had a wonderful visit at the plant that day. Again, hosted by all of the management people that were working at the time. We were actually there when they were in strike, but we had a great visit. We spent the balance of that weekend at Niagara on the Lake, which is a delightful little theater town up there, and we were able to visit Niagara Falls. The other international trip was a 10-day trip to Slovakia. U.S. Steel had bought the steel company in Slovakia in Košice and we spent probably about a week visiting Vienna and Prague, and we spent quite a few days driving across the lovely countryside there in Slovakia and had a couple of just great days with the people at the plant at Košice. In addition to the tour of the plant and a walking tour of the town, they hosted a number of events. They included spouses in some of the events, and they had some delightful Slovakian entertainment for us. So, again, there are examples of the support that we had from the corporation even on these international trips.

The Ciloet trip to New York in 1997 to visit the financial offices.

I think the other thing about the trips that I always found wonderful and I think others will probably agree is that we were traveling with a great group of women. These were women who were coworkers and friends, and I think that made the trips extra special also. I know there are so many good memories of the trips, and talking about the friendship and the fellowship—in the original objectives of the organization, that first group of women, one of their objectives was to provide for other U.S. Steel women who will follow a means for both fellowship and fun, so I think the trips really helped accomplish that. As I said, I think there are many wonderful memories that we all have of the times that we shared on those trips.

I might add too, that in planning these trips, we did not use travel agencies. We did plan all of the details of the trips. It took a lot of effort by a lot of people, and the women who are participating today were all involved and were always willing to share the work, the responsibilities. But again, it was fun working together. I think we stayed together quite a few years doing this, so I guess we always enjoyed it, and it added to our getting to know each other better.

In fact, I really did not know Marylin and Bonnie all that well before I retired. I knew who they were, but we really didn’t know each other that well. And, I always kid Bonnie; she was nominating chair the year I retired. I retired in March, and I tell her that I was home doing some housecleaning when the phone rang, and it was Bonnie and her co-chair of that nominating committee that asked me to be president, so that sounded good after a day of doing house work. But it was really through involvement at Ciloets that we’ve become friends. We know each other’s families, we do other social things together, so I think a lot of friendships were forged over the years through Ciloets.

MR: What I liked about it too was that there were times we had socials, [and] you would see these people at work all the time, but you never saw them in another type of situation. We would have amateur hour, we would have … groups get together and do some singing or whatever. We saw these people at work, and we saw them at the meetings, and on our trips, but to see another side … Even the advisors would get involved in some of our social activities and join in with the ladies. Very good memories of every aspect of the Ciloets, from being involved, and that’s important. You have to be involved in order to understand and grow with the organization, which I think we all have grown and learned a lot, met a lot of people. Like I said, I worked at research, and I really didn’t know anyone from downtown or even at Muriel Street when I had to deal with these people by phone. And once we were all together as far as in the Ciloets organization, we became a family and really, like Donna said, with not only work, but Ciloets have maintained a wonderful friendship with so many wonderful, wonderful people. It’s been great.

What led each of you to want to get into the steel industry? Did any of you have any family connections of people who immigrated here to work in the industry?

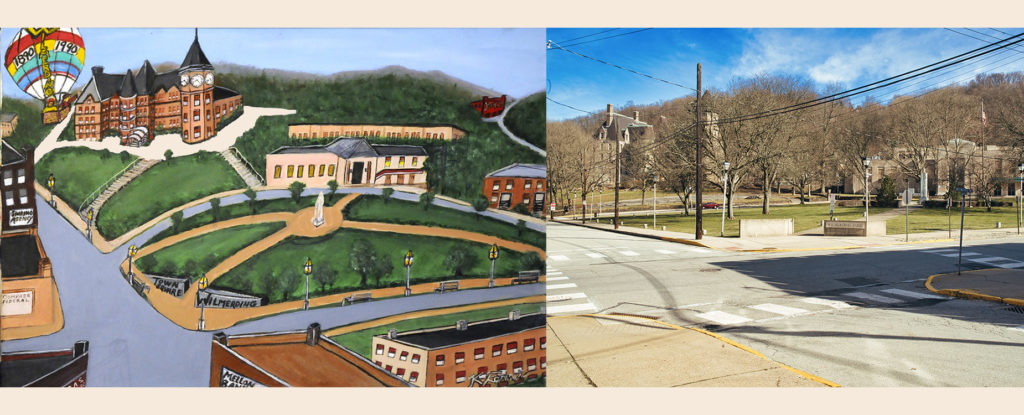

LR: Well my grandfather was actually an employee of U.S. Steel; he came over from Slovakia as well, actually from the Košice area where [U.S. Steel] bought the plant. My uncle worked down at National Tube, my other uncle was an accountant for U.S. Steel. My dad actually worked for U.S. Steel for a while. I think if you were born in Pittsburgh, you probably knew for somebody or were related to somebody that at one point worked for U.S. Steel. None of that actually got me, necessarily, into U.S. Steel. I think, a lot on the union side, yeah they would bring their sons and other relatives in preferentially maybe through the union, but on my side, I just became an engineer, I happened to like metallurgy, and then I happened to go to U.S. Steel, but I did have a legacy of U.S. Steel in my family. I don’t know that it necessarily prompted me to begin a position there and stay there for so long. And I met my husband at U.S. Steel … We met at Research playing volley ball of all things—not working together at all, different sides of the spectrum in terms of the operation. But certainly we moved with U.S. Steel, and U.S. Steel made it very easy for us to be a couple, and a couple working at U.S. Steel.

DD: Yes, actually. My grandfather also worked at Edgar Thomson, and he also came from Slovakia, so there is that history in my background also. But I think what really drew a lot of us to U.S. Steel—it was a major employer, and it was a very well-respected company. It was a company that contributed a lot to the Pittsburgh area in many ways. In the theater programs over the years, you always saw U.S. Steel as one of the major contributors. The Foundation did a lot in terms of contributing to many aspects of the cultural life of Pittsburgh. And I’m sure there are people that worked for Westinghouse and Alcoa—there were a number of large corporations that probably had employees that felt the same about those corporations also. It was certainly a place where people wanted to work, at least I think women. It was a big employer of men, whether or not it was their first choice of employment, I don’t know if that was always the case. But it was a major employer in the Pittsburgh area, so a lot has changed in that respect now; but back when we were hired, it made an impact here in the city, the corporation.

Can you talk a bit about your hours, and what your work day, work week was like in terms of stress levels and things that were on your plate for the day, the projects you worked on? Without being too personal, in terms of salary was something that was able to sustain you comfortably? And if you’d want to share details about the everyday parts of your workday, like the things that you ate for lunch, or what you wore to work.

DD: I think one of the things that made U.S. Steel a desirable place to work was that it did pay employees well. Women that came into the organization even on secretarial jobs, I think salaries were very competitive. The other companies again—there were others that were also excellent employers, but that, I think, definitely is one of the things that made the corporation so attractive to people.

Those of us working at headquarters, and I think also at Tech Center, when I first started, headquarters was across the street from where Kaufmann’s had been at 525 William Penn Place, and we had a large employee cafeteria there, so most everyone ate in the cafeteria. But when we moved into the new building, they did not include an employee cafeteria. So the cafeteria was always a place for socializing and seeing employees also. U.S. Steel had, at headquarters, had, we called it the “Andrew Carnegie Athletic Association.” It was an employee organization that sponsored many kinds of events and activities. They actually, way back, did golf weekends and many other activities. So, it was a good place to work for many reasons.

MR: The reason I think I decided to pursue a job opportunity at U.S. Steel—it wasn’t far from home, I could get there very easily, and fortunately I did get the job there. It was nice working at this location, the research center in Monroeville. We didn’t have to pay for parking; you could just park your car and go into work. The type of socializing, as far as the Tech Center was concerned, we had a Tech Center Club that we all—you didn’t have to belong to, but the majority of us did. They had a bowling league, they had a golf league, they had a volleyball league… There were always other activities going on that brought us together outside of the office. And as far as our lunch bag, we were fortunate that we had always maintained a cafeteria, and U.S. Steel would subsidize part of that cafeteria as far as the expenses. So, Tuesdays were prime rib day, and you could get a prime rib dinner for $2.50. It was just a wonderful place to go to every day. Sure there were stress times. There were deadlines you had to meet. But, we worked together as a team in the office that I worked in, and we got through what we had to do. But also, making good friendships and good memories of U.S. Steel.

BG: We always had to dress. I mean, there were no pants, and I don’t remember what year it was—Donna might remember this, but they were talking about women wearing pantsuits to the work place, and that was the big deal. And when the chairman of the board’s secretary wore pants, that was our cue that we were allowed to wear pants to work and that was a big deal! And then down the road, it was many years after that, you could come to work casual. So, I saw from the very dressed—heels, nylons, to pantsuits, to casual.

DD: I retired in 1999, and we were just beginning to be able—I think it was on Fridays, that you were permitted to wear pants. So my career really was spent dressing up coming to work except for a few days probably within that last year. That certainly changed over the years, but I enjoyed that. Now when I think back, I’m glad I worked at a time where we dressed up when we went to the office.

MR: I know out at research, especially on a Friday, if one of the engineers had to be called into a meeting in Pittsburgh, they better have a suit jacket and a change of dress pants to go downtown. Because one time a person went down just in their blue jeans and whatever, and they were… we had to make some changes that dress down day, casual day should be khakis and a shirt. You looked nice.

LR: … It was funny, because downtown people would [have casual day], and in the mills they thought it was a little silly to have an event like that because jeans was our daily wear. Jeans and then you changed out of your jeans into your fire-retardant greens, you know. For me, I was in a lot of different roles. When I was downtown you dressed up more.

Certainly later in my career but at a time when I had a lot more responsibility, days were very long. They were 12-, 16-hour days. The plant could be like that all the time, working on weekends. Even coming home and still working, emails and such. So, I mean, when you’re in a position of leadership at any corporation, those are the kinds of hours that you’re going to have to put in. One different thing about working in the mill is the calls. You get called any time of the night, especially if somebody has an injury, if there’s a hiccup in the operations at all, you would get a phone call. And there were times when it was something you could handle over the phone, and there were times when you would go into the office. That was particularly tough when you’re juggling that with a spouse and children, but you make it work. So, the work for managers in the mill, they’re there right with the union guys. They’re working the same hours, but probably more, a lot more responsibility.

When I was running the plants in the Mon Valley, every day I was responsible for the health and safety of 3,000 people, and there’s a lot of stress there. So there’s, safety, there’s quality, there’s environmental—especially in the Pittsburgh area that’s very prominent. And then there’s still operations and costs. So, it’s a very stressful, it’s a very stressful job. And then there’s positions where it’s maybe not as stressful. At Research, if you’re just an engineer, maybe 8 or 10 hour days, but there was a lot of travel. Every job comes with its set of stressors, its set of responsibilities, and usually that ebbs and flows in your career. Anyone, when it’s crunch time and you have to get a report out, or you’re doing union negotiations. Everyone has their times when they’re working significant hours. But there’s a lot of fun, too. Steel gets in your blood, and you just love it.

That sounds like a lot to keep on your mind all the time. Lisa, being the first woman to hold some of the plant management roles that you did, do you think employees interacted with you differently than they did with your male predecessors? Did you run into challenges?

LR: First I was the plant manager at Clairton, and then I was the general manager of the Mon Valley operations. I honestly don’t think I did [run into challenges]. At the time, between myself, and actually having a husband who worked there in some of those plants, I knew a lot of the people before I started. When I went to Clairton though, I had no idea how to make coke or anything like that, and when I went in I was very honest with the guys and I said, “Look I don’t know anything about making coke. Here’s my skills, and this is what I bring to the job, and I will learn. I will learn very fast, and I will let you teach me.” And they did. I guess, listening—making sure you’re listening, taking in a lot of information to make decisions. I think I was very collaborative and respectful of everybody and their knowledge. I didn’t come in like, “I know everything and I’m going to be the manager.” I think that maybe that helped me, and that was my style. I certainly had men tell me what I should do from a style standpoint, and I politely just ignored their advice. I don’t feel I ever was discriminated against, at pretty much any time in my career. If anything, I was given more opportunities, I believe. I don’t know, maybe I was just blind to that, but I really enjoyed my time at the mill. But I did—I brought my skill set there and I was able to fight for the plants and advocate for the plants in my role. And I, I don’t know, maybe you’d ask other people, but I was an engineer all the time, I loved solving problems, I was very quality-oriented and it was a lot of my background in quality and research, and that was what I brought to that role. I think being a mother actually helped in management skills as much as anything else.

Can you tell me what being a Ciloet has been like in more recent years? What kind of topics and speakers are you hearing from during your meetings? Are the mill trips still happening in non-pandemic times?

LR: We haven’t had a mill trip in maybe about five years. The last one that we went to was local in Monroeville. And a lot of that had to do with the economy at the time, and the changes in U.S. Steel. In more recent years, we have had the opportunity to have speakers from the new members of U.S. Steel that have been brought in as a lot of our people had—you know, there’s shake up in the organization. So it was really interesting, I think, to hear a new CFO, a new HR, and in fact we had several HR turnovers. There was a woman that was in charge of the commercial department, there were some very higher-level women that were part of this new regime of executives, so it was neat to hear their perspectives, because a lot of them came from other companies. And U.S. Steel had a long—a long, long, long tradition—of just promoting from within, raising people from the time that they were right out of high school or even college, up to their executive ranks. There was a large loyalty factor, there was a large grow-within factor, and in more recent years, since several years before I retired, so maybe the last eight to ten years, [they started] bringing in people from outside. And I thought that that was probably the most interesting things in terms of speakers. And what was nice about them was that they all agreed—they knew very little about the Ciloets, but they all agreed to come and speak with this organization, and it was really nice to hear their perspectives.

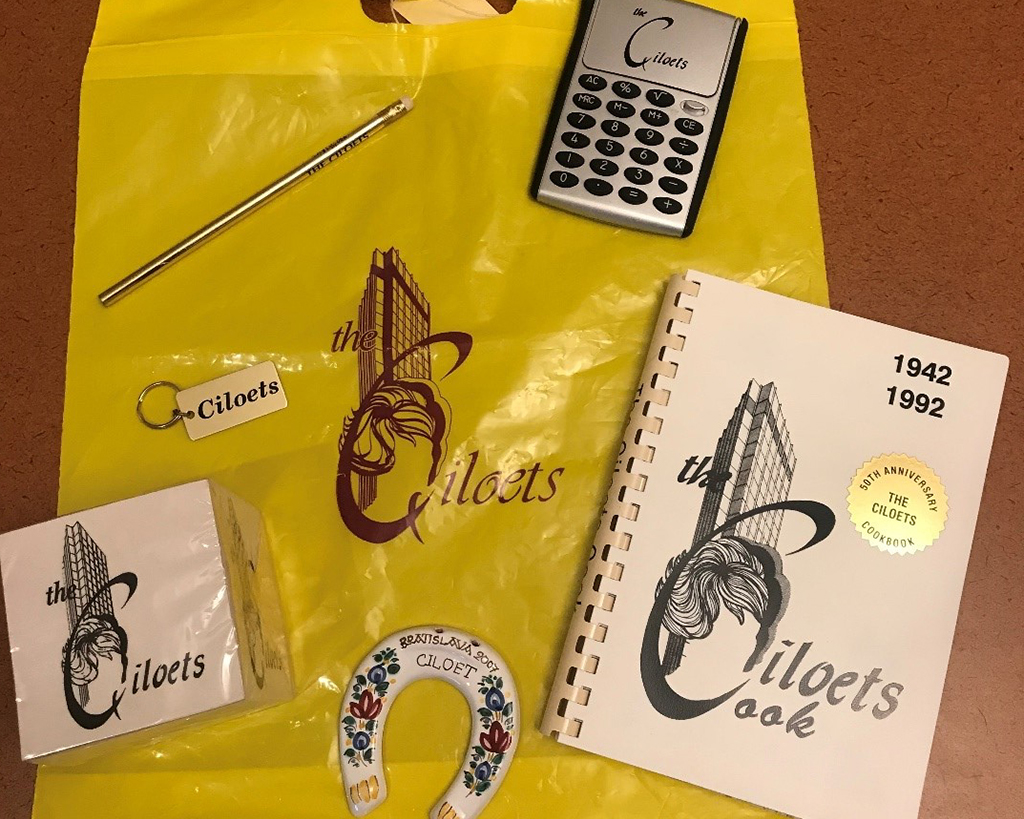

Ciloets items from the Rivers of Steel Archives.

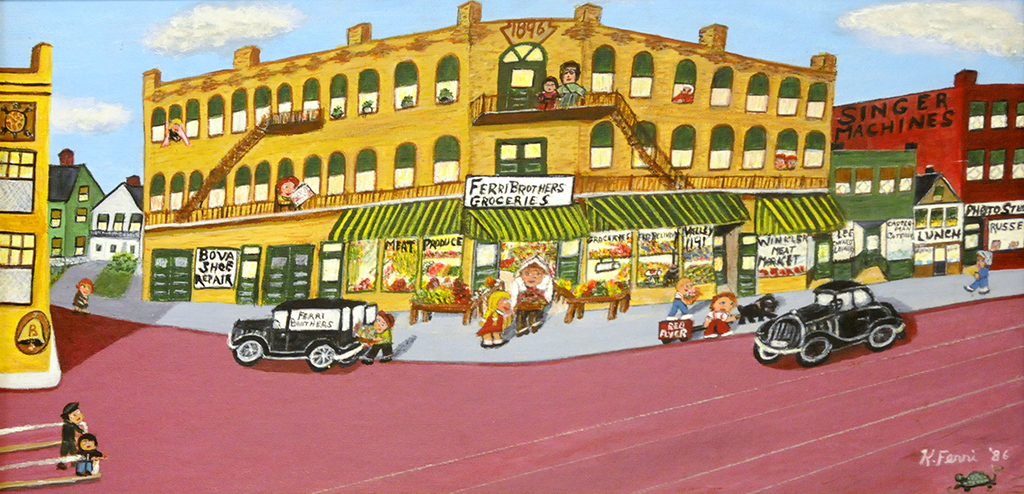

A picture of Kathleen Ferri, c. 2021, with several of her paintings behind her.

A picture of Kathleen Ferri, c. 2021, with several of her paintings behind her.

Bonnie Galla worked in administration for the audit division of the accounting and finance department at U.S. Steel’s Pittsburgh Headquarters for 47 years, from 1967 until retiring in 2014. She has been a Ciloet for 43 years; she joined in September 1978 and has served and chaired different committees. She is a past president of the organization from 1997 to 1998.

Bonnie Galla worked in administration for the audit division of the accounting and finance department at U.S. Steel’s Pittsburgh Headquarters for 47 years, from 1967 until retiring in 2014. She has been a Ciloet for 43 years; she joined in September 1978 and has served and chaired different committees. She is a past president of the organization from 1997 to 1998.

Marylin Roberts worked in administration, employment, and training at U.S. Steel Technology Research Center in Monroeville for 37 years, from 1966 to 2006. She has been a Ciloet for 46 years; since joining in 1975 she has served on committees, and as treasurer and president of the organization. Marylin is currently the membership chair for the Ciloets.

Marylin Roberts worked in administration, employment, and training at U.S. Steel Technology Research Center in Monroeville for 37 years, from 1966 to 2006. She has been a Ciloet for 46 years; since joining in 1975 she has served on committees, and as treasurer and president of the organization. Marylin is currently the membership chair for the Ciloets. Lisa Roudabush worked in plant operations and management at U.S. Steel for 33 years. She began working for the company in 1982 as a student co-op at the Research and Technology Center, and after graduating from college progressed through management roles in that division and at the Gary Works and Mon Valley Works. In 2006, she was appointed as the first woman plant manager of the Clairton Coke Works, and in 2008 became the first woman general manager of the Mon Valley Works. She retired in 2015 as the managing director of quality assurance. She joined the Ciloets in 2006 as a member and as the organization’s advisor. Today she is a retired member and has been president of the Ciloets since 2017.

Lisa Roudabush worked in plant operations and management at U.S. Steel for 33 years. She began working for the company in 1982 as a student co-op at the Research and Technology Center, and after graduating from college progressed through management roles in that division and at the Gary Works and Mon Valley Works. In 2006, she was appointed as the first woman plant manager of the Clairton Coke Works, and in 2008 became the first woman general manager of the Mon Valley Works. She retired in 2015 as the managing director of quality assurance. She joined the Ciloets in 2006 as a member and as the organization’s advisor. Today she is a retired member and has been president of the Ciloets since 2017.

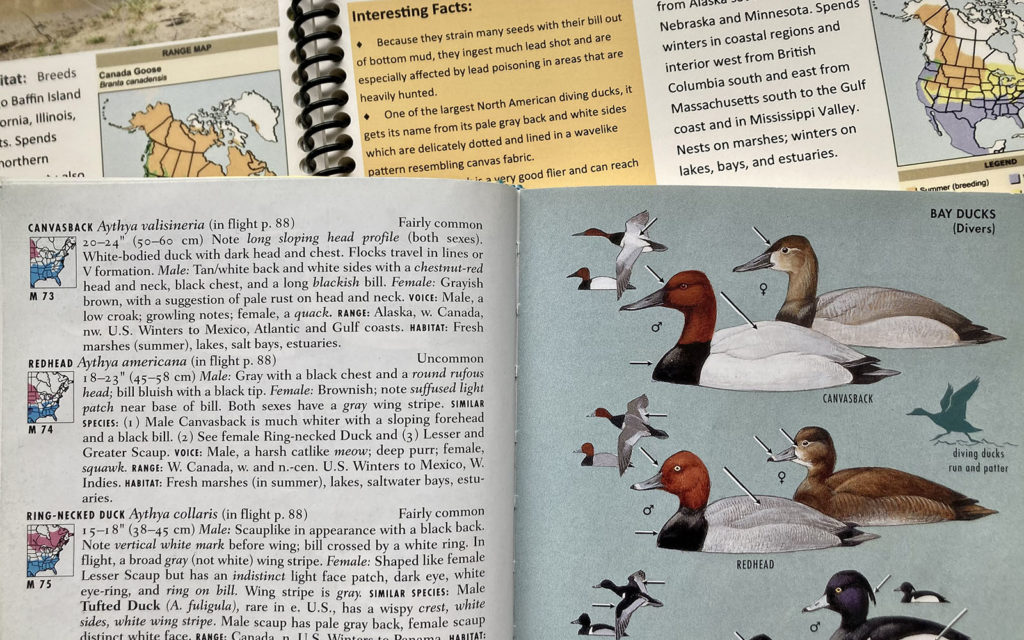

A Tale of Two Ducks: Canvasbacks and Redheads

A Tale of Two Ducks: Canvasbacks and Redheads